A Performer's Guide to Medieval Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TITLE Pages 160518

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/64500 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Young, R.C. Title: La Cetra Cornuta : the horned lyre of the Christian World Issue Date: 2018-06-13 La Cetra Cornuta : the Horned Lyre of the Christian World Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof.mr. C.J.J.M. Stolker, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op 13 juni 2018 klokke 15.00 uur door Robert Crawford Young Born in New York (USA) in 1952 Promotores Prof. dr. h.c. Ton Koopman Universiteit Leiden Prof. Frans de Ruiter Universiteit Leiden Prof. dr. Dinko Fabris Universita Basilicata, Potenza; Conservatorio di Musica ‘San Pietro a Majella’ di Napoli Promotiecommissie Prof.dr. Henk Borgdorff Universiteit Leiden Dr. Camilla Cavicchi Centre d’études supérieures de la Renaissance Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Université de Tours Prof.dr. Victor Coelho School of Music, Boston University Dr. Paul van Heck Universiteit Leiden Prof.dr. Martin Kirnbauer Universität Basel en Schola Cantorum Basiliensis Dr. Jed Wentz Universiteit Leiden Disclaimer: The author has made every effort to trace the copyright and owners of the illustrations reproduced in this dissertation. Please contact the author if anyone has rights which have not been acknowledged. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements vii Foreword ix Glossary xi Introduction xix (DE INVENTIONE / Heritage, Idea and Form) 1 1. Inventing a Christian Cithara 2 1.1 Defining -

Codex Chantilly Discography

Codex Chantilly Discography Compiled by Jerome F. Weber In its original form, this discography of the Codex Chantilly, MS 564 was dedicated to Clifford Bartlett for the 166 issues of Early Music Review and published in the final print issue (No. 166, June 2015). A number of additions and corrections have been made. This version has been formatted to match the Du Fay and Josquin des Prez discographies on this website. The works are listed alphabetically and identified by the index numbers in the facsimile edition published by Brepols in 2008. The recordings are arranged chronologically, citing conductor, ensemble, date of recording if known, and timing if available. Following is the issued format (78, 45, LP, MC, CD, SACD), the label, the issue number(s) and album titles. Eighty-seven out of 112 titles have been recorded. A composer index has been added at the end. Acknowledgment is due to Todd McComb’s website, www.medieval.org/emfaq, and Michael Gray’s website, classical-discography.org for details of some entries. Additions and corrections may be conveyed to the compiler for inclusion in a revised version of the work. Go to Chantdiscography.com and click on ‘contact us’. A scan of a CD booklet that provides needed data would be invaluable. December 2016 In the same series: Aquitanian and Calixtine Polyphony Discography Codex Las Huelgas Discography Codex Montpellier Discography Eton Choirbook Discography 1 Adieu vos di, tres doulce compaynie, 74 (Solage?) Marcel Pérès, Ens. Organum (rec. 1986.09.) [3:38] instrumental LP: Harmonia Mundi HM 1252 CD: HMC 901252; HMT 7901252; HMA 1951252 “Airs de Cour” Crawford Young, Ferrara Ens. -

Ars Subtilior

2015-2016 he Sounds of Time Music of the Ars Subtilior TENET Luthien Brackett mezzo-soprano Jolle Greenleaf soprano Shira Kammen vielle & harp Robert Mealy vielle & harp Kathryn Montoya recorders Nils Neubert tenor Andrew Padgett bass Charles Weaver lute & baritone Jolle Greenleaf artistic director Robert Mealy guest music director 7pm on February 5, 2016 St. Luke in the Fields 487 Hudson Street, New York City 7pm on February 6, 2016 Yale University, Marquand Chapel 409 Prospect Street, New Haven CT Music of the Ars Subtilior I Enigmas and Canons Ma fin est mon commencement Guillaume de Machaut (1300–1377) Tout par compas suy composés (instrumental) Baude Cordier (fl. early 15c) Fumeux fume Solage (fl. late 14c) II Nature, Love, and War Pres du soloil Matteo da Perugia (fl early 14c) Dance (after Machaut) Kammen/Mealy Rose, liz, printemps, verdure Machaut Par maintes foy Jehan Vaillant (fl late 14c) III Mythological Love Se Zephirus, Phebus et leur lignie Magister Grimace (fl mid-14c) De ce que fol (instrumental) after Pierre des Molins (fl mid-14c) Medee fu en amer veritable Anonymous Moult sui (instrumental) Machaut Le Mont Aön de Trace Anonymous Alarme, alarme Grimace 3 TEXT AND TRANSLATIONS Ma fin est mon commencement My end is my beginning Et mon commencement ma fin and my beginning my end: Est teneure vraiement. this is truly my tenor. Ma fin est mon commencement. My end is my beginning. Mes tiers chans trois fois seulement My third line three times only Se retrograde et einsi fin. goes back on itself and so finishes. Ma fin est mon commencement My end is my beginning Et mon commencement ma fin. -

Karl-Ernst Schröder, Lute Crawford Young, Lute

Karl-Ernst Schröder, lute Crawford Young, lute Instruments Renaissance lute in A – Richard C. Earle, Basel 1982 Renaissance lute in A – Richard C. Earle, Basel 2000 Renaissance lute in E – Joel van Lennep, Rindge ( usa ) 1993 5 A production of the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis - Hochschule für Alte Musik Recorded in the Liederhalle (Stuttgart, Germany), in May 2001 Engineered and produced by Andreas Neubronner (Tritonus, Stuttgart) Photographs: A.T. Schaefer (cover) & Thomas Drescher (artists) | Design: Rosa Tendero Executive producer & editorial director ( scb ): Thomas Drescher All texts and translations © 2002 harmonia mundi s. a. / Schola Cantorum Basiliensis Executive producer & editorial director (Gloss a/ note 1 music): Carlos Céster Editorial assistance: María Díaz © 2015 note 1 music gmbh Schola Cantorum Basiliensis – Hochschule für Alte Musik University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland ( fhnw ) www.scb-basel.ch This re-edition is dedicated to the memory of Karl-Ernst Schröder (1958-2003). Amours amours amours 25 Anonymous : Ogni cosa 1:14 26 Alexander Agricola - Johannes Ghiselin (fl .149 1- 1507): Duo 1:56 Lute Duos around 1500 27 Heinrich Isaac : E qui le dira 1:07 28 Heinrich Isaac : De tous bien plaine 1:03 5 29 Francesco Spinacino / Johannes Ghiselin: Juli amours 3:07 30 Francesco Spinacino / Incert.: Je ne fay 1:23 1 Mabriano de Orto (146 0- 1529) : Ave Maria 2:35 31 Josquin Desprez : Adieu mes amours 2:39 2 Jean Rapart (fl .c.147 6- 1481) or Antoine Busnois (c.143 0- 1492): Amours amours amours 2:19 3 Roellrin [Raulin ] / Hayne van Ghizeghem ( c.144 5- 1476/97): De tous biens plaine 1:16 4 Heinrich Isaac (c.1450/5 5- 1517): La morra 2:10 Sources 5 Joan Ambrosio Dalza (fl .1508): Calata 1:36 6 Giovanni Ambrogio : Petits riens 2:11 Prints: 7 Francesco Spinacino (fl .1507) / Anonymous: Jay pris amours 1:26 Harmonice Musices Odhecaton A , Ottaviano Petrucci, Venice 1501 (1, 2, 4, 16, 27, 31) 8 Francesco Spinacino / Josquin Desprez ( c. -

Sequentia's Origins at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis

SEQUENTIA’S ORIGINS AT THE SCHOLA CANTORUM BASILIENSIS by Benjamin Bagby Schola Cantorum, Mittelalterklasse (1975) left to right (upper row): Sally Jans-Thorpe, Anne Smith, Barbara Thornton, Benjamin Bagby, Paul O’Dette (lower row): Catherine Liddell, Harlan Hokin, Alice Robbins. Every ensemble has its origins in a feeling of sympathy among like-minded musicians: at first there are enthusiasms for specific repertoires, perhaps a vision of sound, shared goals, and a lot of late-night discussion, hopefully matched in intensity by endless rehearsal. This was also the case for the origin of Sequentia, which was conceived at the Schola Cantorum in Basel, beginning in 1975 as a student group, and which evolved until the first professional concert under the name ‘Sequentia’ given on 29 March 1977 in Brussels. By the autumn of that year, Sequentia was firmly established in Cologne. What follows are some memories of the ensemble’s beginnings in Basel, and the transition from Basel to Cologne. The crucible in which Sequentia was vocalists Harlan Hokin, Sally Jans-Thorpe, forged was the medieval music perfor- Pilar Figueras, Barbara Thornton and mance class of the ensemble Studio der Benjamin Bagby. Sometimes Hopkinson frühen Musik, under the general direction Smith would also sit in, and in subsequent of Thomas Binkley. As part of a unique years we were joined by others, such as new diploma program for medieval and Sigrid Lee & Dana Maiben (vielles), and renaissance music at the Schola Canto- Candace Smith & Willem de Waal (voic- rum Basiliensis, called into life by Wulf es). I think every one of these musicians Arlt in 1972, their ensemble had been in- would agree today that those were ex- vited to move to Basel from its longtime tremely intense years in Basel. -

TWO LUTES with GRACE Plectrum Lute Duos of the Late 15Th Century

TWO LUTES WITH GRACE Plectrum Lute Duos of the Late 15th Century Marc Lewon • Paul Kieffer • Grace Newcombe TWO LUTES WITH GRACE Pietrobono and the 15th-century Lute Duo fingers of one and the nimble plectrum of the other working Plectrum Lute Duos of the Late 15th Century in harmony. Throughout the song he goes beyond the Acclaimed in his lifetime as ‘the foremost lutenist in the prescribed boundaries and he continually invents new Josquin DES PREZ (c. 1455–1521) Johannes TINCTORIS world’, the Ferrarese virtuoso Pietrobono dal Chitarino rhythms.’ 1 La Bernardina de Josquin * Le souvenir 1:05 (c.1417–1497) remains today without a voice, since we have The wide-ranging repertoire of 15th-century lute duos is no written record of the music he performed at the Italian reflected on this album, with a focus on the French, English, (arr. F. Spinacino, fl. 1507) 1:20 Johannes GHISELIN (fl. 1491–1507) courts in the 15th century. The voices of his fellow and German hit songs of the day: De tous biens playne (7 Alexander AGRICOLA (?1445/46–1506); ( Juli amours (arr. F. Spinacino) 2:54 instrumentalists remain silent as well, since few examples of and ¶, arranged by Roelkin and Tinctoris), Le souvenir (* Johannes GHISELIN (fl. 1491–1507) Anonymous notated music have been preserved. Nevertheless, all is not in a version by Tinctoris), Tout a par moy (™ by the 2 Duo 2:01 ) Tenor So ys enprentyd * 1:34 lost. While contemporary chronicles are very sparing of Englishman Walter Frye, arranged by Tinctoris), and Mit Joan Ambrosio DALZA (fl. -

Symposium Booklet.Pdf

CONTENTS Call for Papers .......................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................. 4 Conference Timetable .............................................................................................. 5 Day 1 ............................................................................................................. 5 Day 2 ............................................................................................................. 6 Day 3 ............................................................................................................. 8 Day 4 ........................................................................................................... 10 Day 5 ........................................................................................................... 12 Locations ................................................................................................................ 13 Abstracts ................................................................................................................. 16 ICTM Paper Presentations .......................................................................... 16 IMS/ICTM Joint Panels ................................................................................ 35 Concert Programme ............................................................................................... 52 About the Performers -

Lewon-Kieffer.Pdf

DEUTSCHE LAUTENGESELLSCHAFT E.V. INTERNATIONALES FESTIVAL DER LAUTE Wolfenbüttel 4.–6. Mai 2018 KONZERT: Sonntag, 6. Mai 2018 13:00 Uhr Schloss Wolfenbüttel, Renaissancesaal „... MIT COLORATUREN GEZYRET“ MARC LEWON — PAUL KIEFFER (Mittelalterlauten) Josquin Desprez, Francesco Spinacino, 1507 La bernardina de Ioskin Lochamer-Liederbuch, ca. 1450 Ich far dohin, wann es muß sein Wolfenbütteler Lautentabulatur, ca. 1460 Ich fare do hyn wen eß muß syn Wolfenbütteler Lautentabulatur, Arr. Paul Kieffer Gruß senen Ich im hertzen traghe Wolfenbütteler Lautentabulatur Ellende du hest vmb vanghen mich Buxheimer Orgelbuch, ca. 1470 Je loe amours „In cytaris vel etiam in organis“ Francesco Spinacino De tous biens Francesco Spinacino Iay pris amours Roellkin De tous biens plaine Johannes Tinctoris, ca. 1430/35–1511 [Alleluja] anonym, spätes 15. Jh. Tandernaken Arrangement Crawford Young Tandernaken Johannes Ciconia, aus: Wolfenbütteler Lautentabulatur Cum lacrimis Johannes Ciconia Gli Atti Wolfenbütteler Lautentabulatur Myn trud gheselle Joan Ambrosio Dalza, 1508 Calata doi lauti Lochamer-Liederbuch, Rekonstruktion Marc Lewon Mit ganzem willen wünsch ich dir Lochamer-Liederbuch, Ar. Crawford Young–Paul Kieffer Mit ganzem willen wünsch ich dir kursiv = Gesang Eintritt frei — um eine angemessene Spende wird herzlich gebeten In Kooperation mit: MARK LEWON Der geborene Frankfurter ist Spezialist für Musik des Mittelalters und der Renaissance. Er studierte Mu- sikwissenschaft und Altgermanistik an der Universität Heidelberg und absolvierte ein Studium der -

CHRISTMAS STORY Artistic Direction by David Fallis, with Guest Tenor Charles Daniels

2019-2020: The Fellowship of Early Music Schütz’s CHRISTMAS STORY Artistic Direction by David Fallis, with guest tenor Charles Daniels DECEMBER 13, 14 & 15, 2019 2019-2020 Jeanne Lamon Hall, Trinity-St.Paul’s Centre Season Sponsor THANK YOU! It is with sincere appreciation and gratitude that we salute The Spem in Alium Fund for its generous support of this production. THANK YOU! It is with sincere appreciation and gratitude that we salute Kevin Finora for generously sponsoring Cory Knight. Join us at our Intermission Café! The Toronto Consort is happy to offer a wide range of refreshments: BEVERAGES SNACKS PREMIUM ($2) ($2) BAKED GOODS ($2.50) Coffee Assortment of Chips Assortment by Tea Assortment of Candy Bars Harbord Bakery Coke Breathsavers Diet Coke Halls San Pellegrino Apple Juice Pre-order in the lobby! Back by popular demand, pre-order your refreshments in the lobby and skip the line at intermission! PROGRAM Lobet den Herrn Heinrich Schütz (1585-1672) Symphonium sacrum II, Op. 10, SWV 350, 1647 Verbum caro factum est Johann Hermann Schein (1586-1630) Cymbalum Sionium, Cantiones Sacræ, 1615 Quem vidistis, pastores? Hans Leo Haßler (1564-1612) Sacri concentus (No. 3), 1601 Auf dem Gebirge Schütz Geistliche Chor-Musik, Op. 11, SWV 396, 1648 Quem vidistis, pastores? Schein Cymbalum Sionium, Cantiones Sacræ, 1615 Das Wort ward Fleisch Schütz Geistliche Chor-Musik, Op. 11, SWV 385, 1648 Alleluja! Lobet den Herren Schütz Psalmen Davids, SWV 38, 1619 INTERMISSION – Join us for the Intermission Café, located in the gym. Historia von der -

Medieval Music©[

Paul Halsall Listening to Medieval Music©[ Author: Paul Halsall Title: Listening to Medieval Music Date: 1999: last revised 01/18/2000] _______________________________________________________________ In the summer of 1999, I made a concerted effort to get a better grasp of medieval music -- better that is, than that acquired by listening to the odd recording here and there. In this document, I outline the general development of music in proto-Western and Western cultures from the time of the earliest information until the beginning of the tonal era, around 1600. Since I am not a musicologist, this outline derives from reading in secondary sources [see bibliography at the end], information supplied with the better CDs and some online sources. Appreciation of almost all serious music is improved by some effort to understand its history and development -- and indeed until very recently any educated person would have had some music education. In the case of Ancient and Medieval music, such effort is essential to enjoyment of the music, unless appreciation is to go no further that a certain "new age" mood setting. For each major period, I list suggested CDs [and occasionally other types of media] which document or attempt to represent the music. These CDs are not the only ones available to illustrate the musical history of Western civilization, but they are however, the ones I have available. [Those marked with * are additional titles that I have not been able to assess personally.] For a much greater selection of available CDs see The Early Music FAQ [http://www.medieval.org/emfaq/], which provides general overviews, and lists of the contents of the vast majority of recordings of early music. -

Rethinking Ars Subtilior: Context, Language, Study and Performance

Rethinking Ars Subtilior: Context, Language, Study and Performance Submitted by Uri Smilansky to the University of Exeter as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Medieval Studies June, 2010 This dissertation is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this dissertation which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. © Uri Smilansky, 2010 Abstract This dissertation attempts to re-contextualise the late fourteenth and early fifteenth century musical phenomenon now referred to as the Ars subtilior, in terms of our modern understanding of it, as well as its relationship to wider late medieval culture. In order to do so I re-examine the processes used to formulate existing retrospective definitions, identify a few compelling reasons why their re-evaluation is needed, and propose an alternative approach towards this goal. My research has led me to analyse the modern preoccupation with this repertoire, both in musicology and performance, and to explore external influences impinging on our attitudes towards it. Having outlined current attitudes and the problems of their crystallisation, I seek to re-contextualise them within medieval culture through a survey of the surviving physical evidence. The resulting observations highlight the difficulties we face when looking at the material. Above all, they point at the problems created by using narrow definitions of this style, whether these are technical, geographic, temporal or intellectual. -

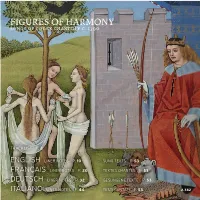

FIGURES of HARMONY Songs of Codex Chantilly C

FIGURES OF HARMONY songs of codex chantilly c. 1390 TRACKLIST P. 2 ENGLISH LINER NOTES P. 10 SUNG TEXTS P. 53 FRANÇAIS LINER NOTES P. 20 TEXTES CHANTÉS P. 53 DEUTSCH LINER NOTES P. 32 GESUNGENE TEXTE P. 53 ITALIANO LINER NOTES P. 44 TESTI CANTATI P. 53 A 382 2 Menu BALADES A III CHANS CD 1 …OF TREBOR AND OTHERS 1 Trebor: Helas pitié envers moy dort si fort 5’58 Chantilly, f. 42 1/4/7 2 Trebor: Se Alixandre et Hector fussent en vie 12’52 Chantilly, f. 30 1/4/5v 3 Baude Cordier: Tout par compas suy composés [instrumental] 2’05 Chantilly, f. 12 4/5v/6 4 Anonymous: Adieu vous di, tres doulce compaynie 3’20 Chantilly, f. 47 3/4/7 5 Matteo da Perugia: Rondeau-refrain [instrumental] 1’46 Florence, f. 16v 4/6/7 6 (?) Matteo da Perugia: Pres du soloil deduissant s’esbanoye 9’54 Modena, f. 16 1/4/5v 7 Antonio da Cividale: Io vegio per stasone [instrumental] 2’26 Siena, f. 47v-48 5l/6/7 8 Anonymous: Lamech Judith et Rachel de plourer 3’12 Chantilly, f. 45 1/6/7 9 Anonymous: Le mont Aon de Thrace, doulz pais 11’02 Chantilly, f. 22v 1/3/4 10 Magister Grimace: Se Zephirus, Phebus et leur lignie 4’41 Chantilly, f. 19 1/2/4 Total time 58’20 SOURCES Chantilly = Chantilly, Bibliothèque du Château, Ms. 564 Florence = Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale, Panciatichi 26 Modena = Modena, Biblioteca Estense, α.M.5.24 Siena = Siena, Biblioteca Comunale, Ms.