Teaching American Literature: a Journal of Theory and Practice Winter 2007 (1:1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Clark Brian Charette Finn Von Eyben Gil Evans

NOVEMBER 2016—ISSUE 175 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM JOHN BRIAN FINN GIL CLARK CHARETTE VON EYBEN EVANS Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East NOVEMBER 2016—ISSUE 175 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : John Clark 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Brian Charette 7 by ken dryden General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Maria Schneider 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Finn Von Eyben by clifford allen Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : Gil Evans 10 by eric wendell [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : Setola di Maiale by ken waxman US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Festival Report Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, CD Reviews Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, 14 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, Miscellany 33 Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Event Calendar 34 Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman Contributing Writers Robert Bush, Laurel Gross, George Kanzler, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman It is fascinating that two disparate American events both take place in November with Election Contributing Photographers Day and Thanksgiving. -

Jazz Flute Repertoire List

Jazz Flute repertoire list 1 September 2016 – 31 December 2022 Jazz Flute Grades Contents Page Introductory Notes .................................................................................................... 3 Publications ................................................................................................................... 4 Downloads ..................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgement ..................................................................................................... 4 Examination Formats ............................................................................................... 5 Free Choice Memory Option .................................................................................. 6 Step 1 ............................................................................................................................... 7 Step 2 ............................................................................................................................... 7 Grade 1 ........................................................................................................................... 8 Grade 2 ........................................................................................................................... 10 Grade 3 ........................................................................................................................... 12 Grade 4 .......................................................................................................................... -

Music Jazz Booklet

AQA Music A level Area of Study 5: Jazz NAME: TEACHER: 1 Contents Page Contents Page number What you will be studying 3 Jazz Timeline and background 4 Louis Armstrong 8 Duke Ellington 15 Charlie Parker 26 Miles Davis 33 Pat Metheny 37 Gwilym Simcock 40 Essay Questions 43 Vocabulary 44 2 You will be studying these named artists: Artists Pieces Louis Armstrong St. Louis Blues (1925, Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith) Muskrat Ramble (1926, Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five) West End Blues (1928, Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five) Stardust (1931, Louis Armstrong and his Orchestra) Duke Ellington The Mooche (1928, Duke Ellington and his Orchestra) Black and Tan (1929, Duke Ellington and his Orchestra) Ko-Ko (1940, Duke Ellington and his Orchestra) Come Sunday from Black, Brown and Beige (1943) Charlie Parker Ko-Ko (1945, Charlie Parker’s Reboppers) A Night in Tunisia (1946, Charlie Parker Septet) Bird of Paradise (1947, Charlie Parker Quintet) Bird Gets the Worm (1947, Charlie Parker All Stars) Miles Davis So What, from Kind of Blue (1959) Shhh, from In a Silent Way (1969) Pat Metheny (Cross the) Heartland, from American Garage (1979) Are you Going with Me?, from Offramp (1982) Gwilym Simcock Almost Moment, from Perception (2007) These are the Good Days, from Good Days at Schloss Elamau (2014) What you need to know: Context about the artist and the era(s) in which they were influential and the effect of audience, time and place on how the set works were created, developed and performed Typical musical features of that artist and their era – their purpose and why each era is different Musical analysis of the pieces listed for use in your exam How to analyse unfamiliar pieces from these genres Relevant musical vocabulary and terminology for the set works (see back of pack) 3 Jazz Timeline 1960’s 1980’s- current 1940’s- 1950’s 1920’s 1930’s 1940’s 1960’s- 1980’s 1870’s – 1910’s 1910-20’s St. -

All Blues: a Study of African-American Resistance Poetry. Anthony Jerome Bolden Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1998 All Blues: A Study of African-American Resistance Poetry. Anthony Jerome Bolden Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Bolden, Anthony Jerome, "All Blues: A Study of African-American Resistance Poetry." (1998). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6720. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6720 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Charlie Parker Fakebook Software for Windows, Mac Or Realbook Software Plugin

RealBookSoftware.com presents Charlie Parker Fakebook Software For Windows, Mac or RealBook Software Plugin Song Title Ah-Leu-Cha (Ah Lev Cha) Another Hairdo Anthropology Au Privave (No. 1) Au Privave (No. 2) Back Home Blues Ballade Barbados Billie’S Bounce (Bill’S Bounce) The Bird Bird Gets The Worm Bloomdido Blue Bird Blues (Fast) Blues For Alice Buzzy Card Board Celerity Chasing The Bird Cheryl Chi Chi Confirmation Constellation Cosmic Rays Dewey Square Diverse Donna Lee K. C. Blues Kim (No. 1) Kim(No2) Klaun Stance Koko Laird Baird Leap Frog Marmaduke Merry-Go-Round Mohawk (No.1) Mohawk (No 2) Moose The Mooche My Little Suede Shoes Now’S The Time (No. 1) Now’S The Time (No. 2) Ornithology An Oscar For Treadwell Parker’S Mood Passport Perhaps Red Cross Relaxing With Lee Scrapple From The Apple Segment Shawnuff She Rote (No.1) She Rote (No 2) Si Si Steeplechase Thriving From A Riff Visa Warming Up A Riff Yardbird Suite This is available as Instant downloads and DVDs for Windows and Mac and as a Plugin for the RealBook Software Many people use the “Download and DVD” option in order to have instant gratification as well as the security of having a backup copy for future use. (That option runs around $18 more which is the cost of production and shipping) ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Click a link below to be taken to the order form ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Windows Download Plugin Download Mac Download Windows DVD Plugin DVD Mac DVD Windows Download & DVD Plugin Download & DVD Mac Download & DVD . -

By Charlie Parker VERVE 8005 J = 208 (4-Bar Intra) ~"' ~N~

CHARLIEPARKEROMNIBOOK For C Instruments(TrebleClef) • TranscribedFrom His RecordedSolos• TransposedTo Concert Key CONTENTS Title Page AH-LEU·CHA (AH LEV CHA) 86 ANOTHER HAIRDO 104 ANTHROPOWGY 10 AU PRIVAVE (No.1) 24 AU PRIVAVE (No.2) 26 BACK HOME BLUES 106 BALLADE 142 BARBADOS 70 BILLIE'S BOUNCE (BILL'S BOUNCE) 80 THE BIRD . .. .. 110 BIRD GETS THE WORM '" : . .. 94 BWOMDIDO 108 BLUE BIRD :......................... 84 BLUES (FAST) 124 BLUES FOR ALICE 18 BUZZy 78 CARD BOARD 92 CELERITY 22 CHASING THE BIRD 82 CHERYL 58 CHI CHI 28 CONFIRMATION 1 CONSTELLATION 45 COSMIC RAYS " 30 DEWEY SQUARE 14 DIVERSE 114 DONNA LEE . .. .. .. .. 48 K. C. BLUES 20 KIM (No.1) 51 KIM (No.2) 54 KLAUN STANCE 89 KOKO 62 LAIRD BAIRD 32 LEAP FROG 130 MARMADUKE 68 MERRY·GO·ROUND 117 MOHAWK (No.1) 38 MOHAWK (No.2) 40 MOOSE THE MOOCHE 4 MY LITTLE SUEDE SHOES 120 NOW'S THE TIME (No.1) 74 NOW'S THE TIME (No.2) 76 ORNITHOWGY 6 AN OSCAR FOR TREADWELL . .. 42 PARKER'S MOOD 134 PASSPORT 102 PERHAPS 72 RED CROSS 66 RELAXING WITH LEE 122 SCRAPPLE FROM THE APPLE. 16 SEGMENT 97 SHAWNUFF. .. .. .. 128 SHE ROTE (No.1) 34 SHE ROTE (No.2) 36 mm STEEPLECHASE . .. .. 112 THRIVING FROM A RIFF 60 VISA 100 WARMING UP A RIFF . .. .. .. .. .. .. 136 YARDBIRD SUITE........................ 8 Charlie Parker (Biography) ii Introduction iv Scale Syllabus 143 'i'J1978 ATLANTlC MUSIC CORP. International Copyright Secured Made in U.S.A. All Rights . " INTRODUCTION The solos in this book represent a cross section of the music of Charlie Parker. -

8. BIRD's EYES Vol. 26-156

BIRD'S EYES Vol. 26-156 series C ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ BIRD'S EYES PHILOLOGY VOL. 26 (W 857) varia Early 1937, Kansas City : 01 Honeysuckle Rose into Body and Soul (long version) 5'25 Note : edit ! February 15, 1943 , Chicago, Savoy Hotel, Room 305 Fragments (Bob Redcross : Bird on tenor) the unofficial Redcross fragments 02 Indiana (2 fragments) 4'17 03 Indiana 1'40 04 Oh! Lady Be Good 2'00 January 18 / 24, 1954, Boston, Hi-Hat Club 05 (end of) My Little Suede Shoes 1'26 06 into 52nd Street Theme 0'29 closing SST 0'39 Spring 1947, West Coast 07 How High The Moon 1'22 Place Unknown, 31.12.1950 08 This Time The Dream's On Me 2'30 February , 1943 , Chicago, Savoy Hotel, Room 305 the official, complete, Redcross Jam Session 09 Sweet Georgia Brown #1 (partial) 3'33 10 Sweet Georgia Brown #1 (partial) 3'58 11 Three Guesses (On " I Got Rhythm " 1) 4’38 12 Boogie Woogie 3'14 13 Yardin' With Yard : Shoe Shine Swing) 3'58 14 Body And Soul 3 (2 fragments) 1’35 16 Embraceable You 2’36 17 China Boy 2’34 18 Avalon 2’42 19 Indiana 1’48 20 Oh Lady Be Good (fragment) 0'38 21 Sweet Georgia Brown #2 3’20 22 Lover, Come Back To Me (03.02.1946) 3’31 Note : Body And Soul 3 begins on track 14 and goes on on track 15. Track 20 identical in Stash & Masters of Jazz Bird's Grafton (the plastic white one) at Christie's Auction on September 7, 1994 (Beaten at 1000.000 $) played by Pete King (as, mc), Steve Melling (pn), Alec Dankworth (b) & Steve Keoph (d) 23 Parker's Mood 0'44 into Confirmation 6'08 Lover Man 6'24 Wee 3'30 closing 0'20 total time : 16'22 total time : 73'04 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ BIRD'S EYES VOL. -

Vincent Herring Eric Harland Hugh Steinmetz Tadd Dameron

AUGUST 2017—ISSUE 184 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM NELS CLINE music for lovers VINCENT ERIC HUGH TADD HERRING HARLAND STEINMETZ DAMERON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East AUGUST 2017—ISSUE 184 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : vincent herring 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : ERIC HARLAND 7 by marilyn lester General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : NELS CLINE 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : HUGH STEINMETZ by andrey henkin Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : TADD DAMERON 10 by stuart broomer [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : CIRCUM-DISC by ken waxman US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] IN Memoriam Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival REport Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD ReviewS 14 Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Miscellany 31 Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Event Calendar 32 Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Mathieu Bélanger, Robert Bush, Ori Dagan, Laurel Gross, A generation is loosely defined as those born within a ten-year period, given such colorful George Kanzler, Matthew Kassel, epithets as Baby Boomers, Gen-Xers and Millennials. -

What I Love About Charlie Parker

What I Love About… Charlie Parker By Austin Vickrey Charlie Parker - Overview • Born - August 29, 1920, Kansas City, Missouri • Died - March 12, 1955, New York City, New York • Began saxophone at 11 years old, began professional career at 15 years old. • Nicknames: “Yardbird,” “Bird” • Spent 3-4 years practicing up to 15 hours a day • One of the biggest innovators of bebop style jazz. Charlie Parker - Overview • Influences: Count Basie Band, Bennie Moten Band, Buster Smith (mentor), Lester Young • Famous cymbal throw by Jo Jones (drummer for Basie), prompted a woodshed period for a year • Bands: Jay McShann, Earl Hines, became leader of his own band • Developed bebop concept along with: Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonius Monk, Max Roach, Bud Powell. • Checkered history with drugs (heroin), would get clean but it wouldn’t take. • Died at 34 years old - pneumonia, bleeding ulcer, cirrhosis, heart attack. Coroner mistakenly thought his age was between 50-60 years old. Charlie Parker - Impact on me as a musician • I started saxophone at 11 years old and heard Charlie Parker when I was 13/14 years old. • Heard Parker on a cassette tape after my first jazz lesson. • Song: A Night in Tunisia - Charlie Parker All-Stars - Solo Break • I purchased the Charlie Parker Omnibook (transcriptions) and proceeded to try to find as many recordings as I could. • Bird has been my main influence in music Charlie Parker - What grabs me about his music • The virtuosic playing (Night in Tunisia solo break) • Fluidity of ideas • Melodies of his compositions - Contrafacts • Sound an expression - rooted in the blues • Charlie Parker - Notable Recordings • 1945 - Savoy label - Charlie Parker’s Reboppers Significant tracks: “Ko- Ko,” “Billie’s Bounce,” “Now’s the Time” • 1949 - Charlie Parker with Strings - Norman Granz arranged for session. -

Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected]

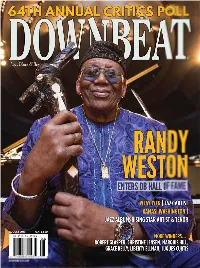

August 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 8 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael -

Charlie Parker.Indd

Charlie Parker 1. Swingmatism (W. Scott – J. McShann) 2:41 2. The Jumpin‘ Blues (J. McShann) 3:06 3. Tiny‘s Tempo (Grimes – Hart) 2:54 4. I‘ll Always Love You (L. Grimes) 3:00 5. Romance Without Finance (L. Grimes) 3:03 6. Red Cross (C. Parker) 3:08 7. Dream Of You (Oliver – Lunceford – Moran) 2:52 8. Groovin‘ High (J.B. Gillespie) 2:39 9. Dizzy Atmosphere (J.B. Gillespie) 2:47 10. All The Things You Are ( J. Kern – O. Hammerstein) 2:46 11. Salt Peanuts (J. B. Gillespie) 3:15 12. Shaw ‘Nuff (J. B. Gillespie) 2:59 13. Hot House (T. Dameron) 3:08 14. Hallelujah (Youmans – Robin – Grey) 3:59 15. Get Happy (Arlen – Koehler) 3:41 16. Slam Slam Blues (S. Stewart) 4:27 17. Congo Blues (Smith) 3:52 18. Takin ‘Off (C. Thompson) 3:08 19. 20th Century Blues (C. Thompson) 2:55 20. The Street Beat (C. Thompson) 2:32 21. Warming Up A Riff (C. Parker) 2:34 22. Billie‘s Bounce (C. Parker) 3:10 23. Now‘s The Time (C. Parker) 3:16 24. Thriving On A Riff (C. Parker) 2:54 25. Meandering (P. David) 3:16 26. Ko-Ko (C. Parker) 2:55 27. Dizzy‘s Boogie (B. Gaillard) 3:09 28. Flat Floot Floogie (B. Gaillard) 2:32 29. Poppity Pop (Gaillard – Stewart) 2:57 30. Slim‘s Slam (Gaillard – Stewart) 3:14 31. Diggin‘ Diz (G. Handy) 2:52 32. Moose The Mooche (C. Parker) 3:03 33. Yardbird Suite (C. -

Charlie Parker - the Complete Scores Discography

Charlie Parker - The Complete Scores discography Ah-Leu-Cha, The Complete Savoy & Dial Master Takes, SVY 17149, Disc 3, Track 16 Anthropology, Jazz Master - Charlie Parker, Star Evens digital release, Track 1 Au Privave, Bird’s Best Bop on Verve, Verve 527 452-2, Track 5 Barbados, The Complete Savoy & Dial Master Takes, SVY 17149, Disc 3, Track 15 Billie’s Bounce, The Complete Savoy & Dial Master Takes, SVY 17149, Disc 1, Track 6 Bird Feathers, The Complete Savoy & Dial Master Takes, SVY 17149, Disc 2, Track 21 Bird’s Nest, The Complete Savoy & Dial Master Takes, SVY 17149, Disc 2, Track 1 Bloomdido, Bird’s Best Bop on Verve, Verve 527 452-2, Track 2 Blues For Alice, Bird’s Best Bop on Verve, Verve 527 452-2, Track 9 Bongo Bop, The Complete Savoy & Dial Master Takes, SVY 17149, Disc 2, Track 16 Chasing The Bird, The Complete Savoy & Dial Master Takes, SVY 17149, Disc 2, Track 8 Chi Chi, Now’s The Time: The Genius of Charlie Parker, Verve MGV 8005, Track 7 Confirmation, Bird’s Best Bop on Verve, Verve 527 452-2, Track 16 Dewey Square, The Complete Savoy & Dial Master Takes, SVY 17149, Disc 2, Track 17 Dexterity, The Complete Savoy & Dial Master Takes, SVY 17149, Disc 2, Track 15 Donna Lee, The Complete Savoy & Dial Master Takes, SVY 17149, Disc 2, Track 7 Drifting On A Reed, The Complete Savoy & Dial Master Takes, SVY 17149, Disc 3, Track 5 K. C. Blues, Bird’s Best Bop on Verve, Verve 527 452-2, Track 7 Kim, Now’s The Time: The Genius of Charlie Parker, Verve MGV 8005, Track 3 Klactoveededstene, The