Understanding Practices of Stakeholder Engagement and Mineral Supply Chain Due Diligence in the Electronics Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIGO Scientists Make First-Ever Observation of Gravity Waves

Stories Firehose All Popular Polls Deals Submit Search Login or Sig1n2 u8p Topics: Devices Build Entertainment Technology Open Source Science YRO Follow us: Slashdot is powered by your submissions, so send in your scoop Nickname: Password: 6-20 characters long Public Terminal Log In Forgot your password? Sign in with Google Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Close Check out the brand new SourceForge HTML5 speed test! Test your internet connection now. Works on all × devices. Second Gravitational Wave Detected From Ancient Black Hole Collision (theguardian.com) Posted by BeauHD on Wednesday June 15, 2016 @11:30PM from the ripples-in-the-fabric-of-spacetime dept. An anonymous reader quotes a report from The Guardian: Physicists have detected ripples in the fabric of spacetime that were set in motion by the collision of two black holes far across the universe more than a billion years ago. The event marks only the second time that scientists have spotted gravitational waves, the tenuous stretching and squeezing of spacetime predicted by Einstein more than a century ago. The faint signal received by the twin instruments of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) in the US revealed two black holes circling one another 27 times before finally smashing together at half the speed of light. The cataclysmic event saw the black holes, one eight times more massive than the sun, the other 14 times more massive, merge into one about 21 times heavier than the sun. In the process, energy equivalent to the mass of the sun radiated into space as gravitational waves. Writing in the journal Physical Review Letters on Wednesday, the LIGO team describes how a second rush of gravitational waves showed up in their instrument a few months after the first, at 3.38am UK time on Boxing Day morning 2015. -

Time to Reboot.Indd

TIME TO REBOOT II About Toxics Link: Toxics Link emerged from a need to establish a mechanism for disseminating credible information about toxics in India, and for raising the level of the debate on these issues. The goal was to develop an information exchange and support organisation that would use research and advocacy in strengthening campaigns against toxics pollution, help push industries towards cleaner production and link groups working on toxics and waste issues. Toxics Link has unique experience in the areas of hazardous, medical and municipal wastes, as well as in specifi c issues such as the international waste trade and the emerging issues of pesticides and POP’s. It has implemented various best practices models based on pilot projects in some of these areas. It is responding to demands upon it to share the experiences of these projects, upscale some of them and to apply past experience to larger and more signifi cant campaigns. Copyright © Toxics Link, 2015 All rights reserved FOR FURTHER INFORMATION: Toxics Link H-2, Jungpura Extension New Delhi – 110014 Phone: +91-(11)-24328006, 24320711 Fax: +91-(11)-24321747 Email: [email protected] Web: www.toxicslink.org Report: Priti Banthia Mahesh Data Collection: Monalisa Datta, Vinod Kumar Sharma ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Time to Reboot was released last year and received good response from all around. Offi cers from Regulatory Agencies, Industry, Civil society organisaions and experts welcomed the idea, prompting us to plan the next edition. Feedback, both positive and negative, also helped us in redefi ning the criteria and we would like to take this opportunity to thank all of them. -

The Oklahoma Computer Equipment Recovery Act: a Summary of the 2014 Manufacturer Annual Reports

The Oklahoma Computer Equipment Recovery Act: A Summary of the 2014 Manufacturer Annual Reports 6/23/2015 Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality Melissa Adler-McKibben Submitted To: The Governor, the President Pro Tempore of the Senate, and the Speaker of the House of Representatives [1] Introduction The Oklahoma Computer Equipment Recovery Act (“Act”), 27A O.S. § 2-11-601 et seq ., was signed into law on May 12, 2008 and became effective on January 1, 2009. The Act requires manufacturers, as defined in 27A O.S. § 2-11-603, to submit annual reports to the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality (“DEQ”) no later than March 1 st of each year that include: 1. A summary of the recovery program implemented by the manufacturer during the previous calendar year, specifically describing the methods of recovery implemented by the manufacturer; 2. The weight of covered devices collected and recovered during the previous calendar year; 3. The location and dates of any electronic waste collection events during the previous calendar year, if any, and the location of collection sites if any; and 4. Certification that the collection and recovery of covered devices complies with the provisions of Section 9 of the Act. 1 The Act requires DEQ to summarize the recovery program in a report for the Governor, the President Pro Tempore of the Senate, and the Speaker of the House of Representatives. Background The Act was created as part of an ongoing, nationwide effort, embraced and supported by the computer industry, to establish convenient and environmentally sound collection, recycling, and reuse of electronics that have reached the end of their useful lives. -

Book of Abstracts

PICES-2016 25 Year of PICES: Celebrating the Past, Imagining the Future North Pacific Marine Science Organization November 2-13, 2016 San Diego, CA, USA Table of Contents Notes for Guidance � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 5 Venue Floor Plan � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 6 List of Sessions/Workshops � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 9 Meeting Timetable � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 10 PICES Structure � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 12 PICES Acronyms � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 13 Session/Workshop Schedules at a Glance � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 15 List of Posters � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 47 Sessions and Workshops Descriptions � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 63 Abstracts Oral Presentations (ordered by days) � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

Vista Procedure

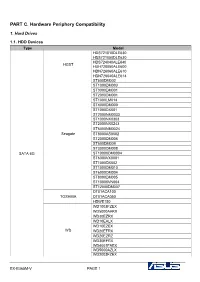

PART C. Hardware Periphery Compatibility 1. Hard Drives 1.1. HDD Devices Type Model HDS721010DLE630 HDS721050DLE630 HDS724040ALE640 HGST HUH728080ALE600 HDN726060ALE610 HDN726040ALE614 ST500DM002 ST1000DM003 ST3000DM001 ST2000DM001 ST1000LM014 ST4000DM000 ST1000DX001 ST2000NM0033 ST1000NX0303 ST2000NX0243 ST6000NM0024 Seagate ST8000AS0002 ST2000DM006 ST500DM009 ST3000DM008 SATA 6G ST10000DM0004 ST6000VX0001 ST1000DX002 ST1000DM010 ST6000DM004 ST8000DM005 ST10000VN004 ST12000DM007 DT01ACA100 TOSHIBA DT01ACA050 HDWE150 WD1003FZEX WD5000AAKX WD30EZRX WD10EALX WD10EZEX WD WD20EFRX WD20EZRZ WD30EFRX WD4001FAEX WD5000AZLX WD2003FZEX EX-B365M-V PAGE 1 Type Model WD20PURX WD10PURX WD60EFRX SATA 6G WD WD60EZRX WD60PURX WD80EFZX WD8002FRYZ SATA 3G Seagate ST31000528AS HGST HTS721010A9E630-4233 TOSHIBA MQ01ABD100-4227 WD20NPVZ-4229 SATA 6G(2.5) WD WD10JPLX-4231 ST1000LX015-4237 Seagate ST2000LM015-4239 1.2. SATA SSD Type Model IS32B-16G ASU800SS-128G-3963 ADATA ASX950SS-240G-4256 SU900-256G-4271 ASX950USS-480G-4369 AMD R3SL120G T1-120G-4342 ANACONDA N2-240G-4348 AST680S-128G AP240GAS720-240G APACER AP240GAS330-240G AP256GAS510SB-256G CSSD-F256GBLX CORSAIR CSSD-F120GBLSB SATA 6G SSD CT250BX100SSD1 CT250MX200SSD1 Crucial CT240BX200SSD1 CT525MX300SSD1 Colorful SL500-640G-4531 FSX-120G FUJITSU F300-240G SSDSC2KW240H6 INTEL SSDSC2BB240G7-4162 KINGBANK KP330-240G-4444 SHSS37A/240G SKC400S37/256G Kingston SUV400S37-240G SA400S37/240GB LITEON MU3-PH4-CE240-240G TRN150-25SAT3-240G TOSHIBA OCZ TL100-25SAT3-240G EX-B365M-V PAGE 2 Type Model PX-256M7VC-256G -

Coming Back Home After the Sun Rises: Returnee Entrepreneurs and Growth of High Tech Industries

G Model RESPOL-2772; No. of Pages 17 ARTICLE IN PRESS Research Policy xxx (2012) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Research Policy jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/respol Coming back home after the sun rises: Returnee entrepreneurs and growth of high tech industries a,b c,∗ d Martin Kenney , Dan Breznitz , Michael Murphree a Department of Human and Community Development, University of California, Davis, United States b Berkeley Roundtable on the International Economy, United States c The Scheller College of Business, Georgia Institute of Technology, United States d Sam Nunn School of International Affairs, Georgia Institute of Technology, United States a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Recently, the role of returnees in the economic development of various East Asian nations has received Received 6 November 2011 much attention. The early literature on the relocation of the most highly trained individuals from a devel- Received in revised form 30 July 2012 oping nation to a developed nation viewed the phenomena as a “brain drain.” Since the 1990s, a new Accepted 4 August 2012 strand of thinking has suggested that for developing nations this was actually a positive phenomenon; as Available online xxx these expatriates studied and then worked abroad, they absorbed technical expertise, managerial, and entrepreneurial skills. These theories stipulated that these expatriates then returned home, and ignited Keywords: a virtuous circle of technological entrepreneurship leading to rapid economic development. Much of this High skilled immigrants Innovation literature gives returnees a critical role in the home country’s take-off period of the local information and communications technology (ICT) industry. -

Appointment of Group Finance Director

27 March 2018 Embargoed until 7.00am Appointment of Group Finance Director Dixons Carphone plc (the "Company") announces the appointment of Jonny Mason to its Board as Group Finance Director, with effect from a date to be confirmed. Jonny has been Chief Financial Officer of Halfords plc since 2015 and was Interim Chief Executive Officer between September 2017 and January 2018. Prior to that Jonny was CFO of Scandi Standard AB, a Scandinavian company which successfully listed in Stockholm in June 2014. Jonny’s early career included CFO at Odeon and UCI Cinemas, Finance Director of Sainsbury’s Supermarkets and finance roles at Shell and Hanson plc. Ian Livingston, Chairman of Dixons Carphone, said: “The Board and I are very pleased to welcome Jonny Mason to the Group. Together with Alex Baldock, we now have a great new team to lead Dixons Carphone.” Alex Baldock, incoming Chief Executive Officer of Dixons Carphone, said: “I am delighted to have Jonny by my side. He has an outstanding track record and brings the experience and qualities we need to take Dixons Carphone into the next phase of its transformation.” Jonny Mason said: “I am thrilled to be joining Dixons Carphone. The business has undergone a tremendous journey over recent years and is well placed to meet customers’ ever growing and complex needs for technology. I have experienced first-hand as a customer the quality of our shops, product and services, from my time living in both the UK and Norway, and I feel proud to join the Group to work with Alex, the Board and our great team of colleagues.” There is no information which is required to be disclosed pursuant to Listing Rule 9.6.13. -

A Review of Indian Mobile Phone Sector

IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM) e-ISSN: 2278-487X, p-ISSN: 2319-7668. Volume 20, Issue 2. Ver. II (February. 2018), PP 08-17 www.iosrjournals.org A Review of Indian Mobile Phone Sector Akash C.Mathapati, Dr.K Vidyavati Assistant Professor, Department of Management Studies, Dr.P G Halakatti College of Engineering, Vijayapura Professor, MBA Department, Sahyadri College of Engineering & Management, Mangaluru Corresponding Author: Akash C.Mathapati, Abstract: The Paper Has Attempted To Understand The Indian Mobile Handset Overview, Market Size, Competitive Landscape With Some Of The Category Data. Also Some Relevant Studies On Indian Mobile Handset And Its Global Comparison Have Been Focused With The Impact On Economy And Society. Keywords: India, Mobile handsets, market size, Global Comparisons, GSM --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 15-01-2018 Date of acceptance: 09-02-2018 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. Introduction India is currently the 2nd second-largest telecom market and has registered strong growth in the past decade and a half. The Indian mobile economy is growing quickly and will contribute extensively to India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), according to report prepared by GSM Association (GSMA) in association with the “Boston Consulting Group” (BCG). The direct and reformist strategies of the GoI have been instrumental alongside solid customer request in the quick development in the Indian telecom division. The administration has empowered simple market section to telecom gear and a proactive administrative and reasonable structure that has guaranteed openness of telecom administrations to the customer at sensible costs. The deregulation of "Outside Direct Investment" (FDI) standards has made the segment one of the top developing and a main 5 business opportunity maker in the nation. -

Compatibility Sheet

COMPATIBILITY SHEET SanDisk Ultra Dual USB Drive Transfer Files Easily from Your Smartphone or Tablet Using the SanDisk Ultra Dual USB Drive, you can easily move files from your Android™ smartphone or tablet1 to your computer, freeing up space for music, photos, or HD videos2 Please check for your phone/tablet or mobile device compatiblity below. If your device is not listed, please check with your device manufacturer for OTG compatibility. Acer Acer A3-A10 Acer EE6 Acer W510 tab Alcatel Alcatel_7049D Flash 2 Pop4S(5095K) Archos Diamond S ASUS ASUS FonePad Note 6 ASUS FonePad 7 LTE ASUS Infinity 2 ASUS MeMo Pad (ME172V) * ASUS MeMo Pad 8 ASUS MeMo Pad 10 ASUS ZenFone 2 ASUS ZenFone 3 Laser ASUS ZenFone 5 (LTE/A500KL) ASUS ZenFone 6 BlackBerry Passport Prevro Z30 Blu Vivo 5R Celkon Celkon Q455 Celkon Q500 Celkon Millenia Epic Q550 CoolPad (酷派) CoolPad 8730 * CoolPad 9190L * CoolPad Note 5 CoolPad X7 大神 * Datawind Ubislate 7Ci Dell Venue 8 Venue 10 Pro Gionee (金立) Gionee E7 * Gionee Elife S5.5 Gionee Elife S7 Gionee Elife E8 Gionee Marathon M3 Gionee S5.5 * Gionee P7 Max HTC HTC Butterfly HTC Butterfly 3 HTC Butterfly S HTC Droid DNA (6435LVW) HTC Droid (htc 6435luw) HTC Desire 10 Pro HTC Desire 500 Dual HTC Desire 601 HTC Desire 620h HTC Desire 700 Dual HTC Desire 816 HTC Desire 816W HTC Desire 828 Dual HTC Desire X * HTC J Butterfly (HTL23) HTC J Butterfly (HTV31) HTC Nexus 9 Tab HTC One (6500LVW) HTC One A9 HTC One E8 HTC One M8 HTC One M9 HTC One M9 Plus HTC One M9 (0PJA1) -

Passmark Android Benchmark Charts - CPU Rating

PassMark Android Benchmark Charts - CPU Rating http://www.androidbenchmark.net/cpumark_chart.html Home Software Hardware Benchmarks Services Store Support Forums About Us Home » Android Benchmarks » Device Charts CPU Benchmarks Video Card Benchmarks Hard Drive Benchmarks RAM PC Systems Android iOS / iPhone Android TM Benchmarks ----Select A Page ---- Performance Comparison of Android Devices Android Devices - CPUMark Rating How does your device compare? Add your device to our benchmark chart This chart compares the CPUMark Rating made using PerformanceTest Mobile benchmark with PerformanceTest Mobile ! results and is updated daily. Submitted baselines ratings are averaged to determine the CPU rating seen on the charts. This chart shows the CPUMark for various phones, smartphones and other Android devices. The higher the rating the better the performance. Find out which Android device is best for your hand held needs! Android CPU Mark Rating Updated 14th of July 2016 Samsung SM-N920V 166,976 Samsung SM-N920P 166,588 Samsung SM-G890A 166,237 Samsung SM-G928V 164,894 Samsung Galaxy S6 Edge (Various Models) 164,146 Samsung SM-G930F 162,994 Samsung SM-N920T 162,504 Lemobile Le X620 159,530 Samsung SM-N920W8 159,160 Samsung SM-G930T 157,472 Samsung SM-G930V 157,097 Samsung SM-G935P 156,823 Samsung SM-G930A 155,820 Samsung SM-G935F 153,636 Samsung SM-G935T 152,845 Xiaomi MI 5 150,923 LG H850 150,642 Samsung Galaxy S6 (Various Models) 150,316 Samsung SM-G935A 147,826 Samsung SM-G891A 145,095 HTC HTC_M10h 144,729 Samsung SM-G928F 144,576 Samsung -

Mintel Reports Brochure

Electrical Goods Retailing - UK - February 2018 The above prices are correct at the time of publication, but are subject to Report Price: £1995.00 | $2693.85 | €2245.17 change due to currency fluctuations. “Spending on electricals held up well in 2017 despite increased pressure on consumers’ finances. However, it was again the non-specialists that were the driver, particularly those with a strong presence online as spending increasingly moves to online channels.” – Nick Carroll, Senior Retail Analyst This report looks at the following areas: BUY THIS Demand is equally being driven by high levels of promotional activity, which whilst successful in driving REPORT NOW short-term sales has the potential in the long run to undermine the pricing integrity of those within the sector. VISIT: • Discounting: friend or foe? store.mintel.com • How can retailers continue to grow if discretionary spending falls? • How can specialists best utilise their expertise in a digital world? CALL: EMEA +44 (0) 20 7606 4533 Brazil 0800 095 9094 Americas +1 (312) 943 5250 China +86 (21) 6032 7300 APAC +61 (0) 2 8284 8100 EMAIL: [email protected] This report is part of a series of reports, produced to provide you with a DID YOU KNOW? more holistic view of this market reports.mintel.com © 2018 Mintel Group Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Confidential to Mintel. Electrical Goods Retailing - UK - February 2018 The above prices are correct at the time of publication, but are subject to Report Price: £1995.00 | $2693.85 | €2245.17 change due to currency fluctuations. Table of Contents Overview What you need to know Products covered in this Report Executive Summary The market Real incomes feeling the squeeze Figure 1: Real wage growth: wages growth vs inflation, January 2014-December 2017 Spending on electricals accelerates in 2017 Figure 2: Consumer spending on all electrical products: market size and forecast (including VAT), 2012-22 Specialists continue to lose share Figure 3: Electrical goods specialists as a % of all consumer spending on electrical goods (incl. -

ICO Issues Monetary Penalty Notice Under DPR 1998

ICO Issues Monetary Penalty Notice under DPR 1998 Released : 09 Jan 2020 RNS Number : 2698Z Dixons Carphone PLC 09 January 2020 Information Commissioner's Office issues Monetary Penalty Notice under Data Protection Act 1998 DSG Retail Limited, a subsidiary of Dixons Carphone plc, has today received a Monetary Penalty Notice from the UK Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) in relation to the historic unauthorised access of customer data previously announced on 13 June 2018 and 31 July 2018. The ICO has imposed a fine of £500,000 under the Data Protection Act 1998. Dixons Carphone Chief Executive, Alex Baldock, said: "We are very sorry for any inconvenience this historic incident caused to our customers. When we found the unauthorised access to data, we promptly launched an investigation, added extra security measures and contained the incident. We duly notified regulators and the police and communicated with all our customers. We have no confirmed evidence of any customers suffering fraud or financial loss as a result. We have upgraded our detection and response capabilities and, as the ICO acknowledges, we have made significant investment in our Information Security systems and processes. We are disappointed in some of the ICO's key findings which we have previously challenged and continue to dispute. We're studying their conclusions in detail and considering our grounds for appeal." Next announcement The Group will publish its Peak Trading Statement on Tuesday 21 January 2020. For further informa on Assad Malic Group Strategy & Corporate Affairs Director +44 (0)7414 191044 Dan Homan Head of Investor Relations +44 (0)7400 401442 Amy Shields Head of External Communications +44 (0)7588 201442 Tim Danaher Brunswick Group +44 (0)207 404 5959 Information on Dixons Carphone plc is available at www.dixonscarphone.com Follow us on Twi er: @dixonscarphone About Dixons Carphone Dixons Carphone plc is a leading mul channel retailer of technology products and services, opera ng 1,500 stores and 16 websites in eight countries.