A Historical Case–The Mohawk Institute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trauma and Survival in the Contemporary Church

Trauma and Survival in the Contemporary Church Trauma and Survival in the Contemporary Church: Historical Responses in the Anglican Tradition Edited by Jonathan S. Lofft and Thomas P. Power Trauma and Survival in the Contemporary Church: Historical Responses in the Anglican Tradition Edited by Jonathan S. Lofft and Thomas P. Power This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Jonathan S. Lofft, Thomas P. Power and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6582-3 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6582-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................................... vii Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Jonathan S. Lofft and Thomas P. Power Chapter One ................................................................................................ 9 Samuel Hume Blake’s Pan-Anglican Exertions: Stopping the Expansion of Residential and Industrial Schools for Canada’s Indigenous Children, 1908 William Acres Chapter Two ............................................................................................ -

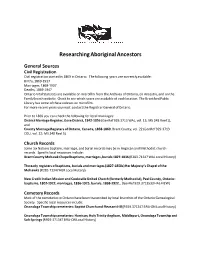

Researching Aboriginal Ancestors

Researching Aboriginal Ancestors General Sources Civil Registration Civil registration started in 1869 in Ontario. The following years are currently available: Births, 1869-1917 Marriages, 1869-1937 Deaths, 1869-1947 Ontario Vital Statistics are available on microfilm from the Archives of Ontario, on Ancestry, and on the FamilySearch website. Check to see which years are available at each location. The Brantford Public Library has some of these indexes on microfilm. For more recent years you must contact the Registrar General of Ontario. Prior to 1869 you can check the following for local marriages: District Marriage Register, Gore District, 1842-1856 (GenRef 929.3713 WAL, vol. 13; MS 248 Reel 1), and County Marriage Registers of Ontario, Canada, 1858-1869, Brant County, vol. 22 (GenRef 929.3713 COU, vol. 22; MS 248 Reel 5) Church Records Some Six Nations baptism, marriage, and burial records may be in Anglican and Methodist church records. Specific local resources include: Brant County Mohawk Chapel baptisms, marriages, burials 1827-1836 (R283.71347 WAL Local History) The early registers of baptisms, burials and marriages (1827-1850s) Her Majesty’s Chapel of the Mohawks (R283.71347 HER Local History) New Credit Indian Mission and Cooksville United Church (formerly Methodist), Peel County, Ontario: baptisms, 1802-1922, marriages, 1836-1925, burials, 1868-1922… (GenRef 929.3713533 HAL-NEW) Cemetery Records Most of the cemeteries in Ontario have been transcribed by local branches of the Ontario Genealogical Society. Specific local resources include: Onondaga Township cemeteries: Baptist Church and Pleasant Hill (R929.371347 BRA-ON Local History) Onondaga Township cemeteries: Harrison, Holy Trinity Anglican, Middleport, Onondaga Township and Salt Springs (R929.371347 BRA-ON Local History) Tuscarora Township Indian burial sites, Ontario Genealogical Society. -

The Hub of Ontario Trails

Conestoga College (Pulled from below Doon) Cambridge has 3 trails Brantford has 2 Trails Homer Watson Blvd. Doon Three distinct trail destinations begin at Brant’s Crossing Kitchener/Waterloo 47.0 kms Hamilton, Kitchener/ Waterloo Port Dover completes the approximate and Port Dover regions are route on which General Isaac Brock travelled Blair Moyer’s Landing Blair Rd. Access Point Riverside Park now linked to Brantford by during the War of 1812. COUNTY OF OXFORD Speed River 10’ x 15” space To include: No matter your choice of direction, you’ll BRANT’S CROSSING WATERLOO COUNTY a major trail system. WATERLOO COUNTY City of Hamilton logo Together these 138.7 kms of enjoy days of exploration between these Dumfries COUNTY OF BRANT Riverblus Park Conservation Access Point G Area e the Trans Canada Trail provide a variety of three regions and all of the delightful o Tourism - web site or QR code r g e S WATERLOOWATERLOO COUNTYCOUNTY t . towns and hamlets along the way. 401 scenic experiences for outdoor enthusiasts. THETHE HUBHUB OFOF ONTARIOONTARIO TRAILSTRAILS N . Cambridge COUNTY OF WELLINGTON 6 Include how many km of internal trails The newest, southern link, Brantford to 39.8 kms N Any alternate routes Pinehurst Lake Glen Morris Rd. COUNTY OF OXFORD W i t Conservation COUNTY OF BRANT h P Concession St. h Area Cambridge Discover Kitchener / Waterloo Stayovers / accommodations i R Access Point e Churchill i Park Three exciting trail excursions begin in Brantford m v Whether you're biking, jogging or walking, of the city is the Walter Bean Grand River e r Myers Rd. -

Oronhyatekha, Baptized Peter Martin, Was a Mohawk, Born and Raised at Six Nations

Oronhyatekha, baptized Peter Martin, was a Mohawk, born and raised at Six Nations. Among many accomplishments, awards, and citations, Oronhyatekha was one of the first of Native ancestry to receive a medical degree. He was also a Justice of the Peace, Consulting Physician at Tyendinaga (appointed by Sir John A. MacDonald), an Ambassador, Chief Ranger of the Independent Order of Foresters, and Chairman of the Grand Indian Council of Ontario and Quebec. But what was perhaps most remarkable about the man was not that he achieved success in the Victorian world, but that he did so with his Mohawk heritage intact. This slide show follows the remarkable life of Oronhyatekha, demonstrating how he successfully negotiated through two worlds, balancing Victorian Values to maintain his Mohawk Ideals. Born at Six Nations on August 10th, 1841, Oronhyatekha was baptized Peter Martin. From the time of his early child hood, he prefered his Mohawk name, which means Burning Sky. “There are thousands of Peter Martins,” he declared, “but there is only one Oronhyatekha.” Oronhyatekha’s character owed much to the influence of his grandfather, George Martin. As a Confederacy chief, George Martin was obliged to uphold the three principles most central to his position: Peace, Power and Righteousness, and raised Oronhyatekha to exemplify those high ideas in his life. Confederacy Chiefs, 1871. Albumen print photograph. Collection of the Woodland Cultural Centre, Brantford, Ontario. Although firmly grounded in the language, traditions and ideals of the Mohawk people, Oronhyatekha entered into the missionary- run school system on the reserve. He first attended the new day school at Martin’s Corners, and later, the Mohawk Institute. -

Evangelist John Saint the Church of of Church the the Evangelist, Evangelist, the Reflections by Fr

The EDITORIAL By Tony Whitehead Evangelist Dear All, How times have changed with St. John's recent commemoration of the canonization of John Henry Newman! Brought up as a Low Anglican in the UK, Newman was regarded as that great 'Anglican turncoat' who - with two others - became Roman Catholics. It is only now I have come to terms with this idea that he is an Anglican hero? Tony Dec. 2019 The Church of Saint John the Evangelist, Montreal 1 Reflections Bishop James had visited St. John’s and Music meeting, the idea was raised of By Fr. Keith Schmidt Bishop Almasi's visit St. Michael’s Mission last time he was in doing something to commemorate this Montreal. After I had given him a brief occasion of Newman’s canonization tour of the mission and the church, he during the Bishop’s visit to St. John’s. It commented that the next time he comes seemed on one hand, that it was an to Montreal, perhaps he could come to St. occasion that we should not ignore, and John’s for a Sunday, because we 'smelled' on the other hand, it would complicate like a real church (the slight smell of our theme for the day which was incense was still in the air). Masasi, and originally simply going to be Harvest that part of Eastern Africa, was heavily Thanksgiving. influenced by Anglo-Catholicism and the Universities’ Mission to Central Africa. It was also suggested that we invite a The well known early twentieth century Roman Catholic representative, and the Anglo-Catholic Bishop, Frank Weston, name of Bishop Tom Dowd, auxiliary had been Bishop of Zanzibar. -

The Chapel Royal, Massey College Gi-Chi-Twaa Gimaa Kwe, Mississauga Anishinaabek Aname Gamik

The Chapel Royal, Massey College Gi-Chi-Twaa Gimaa Kwe, Mississauga Anishinaabek AName Gamik Frequently Asked Questions Key Facts about The Chapel Royal, Massey College Established by Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II, on National Aboriginal Day (June 21st, 2017) The Chapel Royal has been given an Anishinaabek name by James Shawana, Anishinaabek language teacher at Lloyd S King Elementary School in New Credit: Gi-Chi-Twaa Gimaa Kwe, Mississauga Anishinaabek AName Gamik (meaning "The Queen's Anishinaabek sacred place") The result of a partnership between Massey College and the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation The chapel is both interdenominational and interfaith – a first for such a Royal space The third Chapel Royal in Canada The first Anishinaabek Chapel Royal Massey College in the University of Toronto is located on the Treaty Lands (1805 Toronto Purchase) and Territory of the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation The chapel honours and reflects the Silver Covenant Chain of Friendship extended into these lands by the 1764 Treaty of Niagara The chapel was inspired by the Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, specifically #45 The request for Royal Chapel designation for the St Catherine’s Chapel, Massey College, was a commitment to the theme of reconciliation for Canada’s sesquicentennial Canada is unique in having this Indigenous and settler collaboration through the Crown: there is nothing like it anywhere else in the world 1 What is a Chapel Royal? The history of Chapels Royal dates back to the eleventh century in the British Isles. Originally, a Chapel Royal was a body of priests and singers that followed the King or Queen around to attend to their spiritual needs. -

International Law/The Great Law of Peace

INTERNATIONAL LAW/THE GREAT LAW OF PEACE A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for a Masters Degree in the College of Law University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Beverley Jacobs Spring 2000 © Copyright Beverley Jacobs, 2000 . All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done . It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission . It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis . Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the College of Law University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A6 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, this thesis is dedicated to the Hodinohso :m Confederacy, including the Hodiyanehso, the clanmothers, the people, clans and families who have remained strong and true to our traditional way of life . -

Brantford Farmers' Market FRE E

NOVEMBER 2018 BRANTFORD | BRANT SIX NATIONS FREE BSCENE.ca EVENT GUIDE PAGES 13 to 15 Entertainment & Community Guide 44TH ANNUAL BRANTFORD SANTA CLAUS PARADE BSCENE FOOD SCENE Nine North page 5 STORY PAGE 3 BSCENE MUSIC SCENE Fifth Temple page 7 Santa Claus is YOUR NEIGHBOURHOOD EXPERTS page 8 - 9 #BRANTastic Coming to TowN Holiday Shopping Guide page 11 A LOOK BACK Brantford in the 1980’s page 20 - 21 BCHSF Volunteers Have An Im- portant Role at BCHSF page 25 Brantford Farmers’ Market Shop for your Your Holiday party planning starts with quality, fresh and Holiday party at the Brantford local food. Eat seasonally and support our local farmers. Farmers’ PRODUCE • MEATS • CHEESE • PASTRIES • SNACKS Market! Fridays 9:00 am - 5:00 pm • Saturdays 7:00 am - 2:00 pm 79 Icomm Drive 519-752-8824 /Brantford Farmers’ Market Farmers’ –––––––––––––––Market 2 BSCENE.ca Entertainment & Community Guide inside BE SEEN WITH this issue NOV 2018 Vol. 5, Edition 2 Brantford Santa Claus Parade BScene is a local Entertainment & Community Guide, 3 showcasing the #BRANTastic features of Brantford, Goes to the Movies Brant and Six Nations through engaging content and BSCENE with the Best Event Guide in our community. Celebrating Successes at the GRCOA 4 BScene is distributed free, every month through key community partners throughout Brantford, Brant BScene Food Scene and Six Nations. BScene has a local network of over 5 500 distribution points including local advertisers, Nine North retail outlets, dining establishments, and community centres. For a complete list, please visit bscene.ca BScene Music Scene BSCENE AROUND As a community paper and forum for sharing thoughts 7 and experiences, the views expressed in the magazine Fifth Temple are not necessarily those of the Publisher, Editor, other contributors, advertisers or distributors unless Your Neighbourhood Experts 8 - 9 TOWN IN SEPTEMBER otherwise stated. -

The Loyalist Land Holdings in Brantford's Surrounding Areas" (With Surveyor Lewis Burrell's Map of 1833 - PART I)

Selected Reprints from the Grand River Branch Newsletter, Branches "The Loyalist Land Holdings in Brantford's Surrounding Areas" (With Surveyor Lewis Burrell's Map of 1833 - PART I) Angela E.M. Files, February 1993, Vol.5 No.1, Pages 12-14 One of my favorite challenges is to study early maps of Upper Canada, or Canada West, and interpret the place names and persons identified on the maps. Late eighteenth and early nineteenth century maps of Upper Canada, often show the loyalist settlements along the St. Lawrence River, the Great Lakes and the Grand, Ottawa and Thames Rivers. The accompanying map shows the early loyalist land holdings of the area surrounding Brantford, in the 1830's. Surveyor Lewis Burwell, grandson of a loyalist, an early resident of Brantford, surveyed the region. He not only drew a map of the town plot of Brantford and its environs, but also had much to do with the division for settlement of land, either leased or sold by the Six Nations. Leaving a legacy of extensive correspondence with the Superintendent of the Six Nations, John Brant (1794 - 1832), Burwell recorded his place in the annals of local history. By August 13, 1839, Lewis Burwell completed a detailed survey of the area which showed the Brantford town plot having eight streets running east and west and thirteen streets intersecting north and south. On this map, there are fourteen place names, which have early historical significance. Starting on the left corner of the map, I shall attempt to explain some interesting facts about each demarcation. 1. -

Race, Gender and Colonialism: Public Life Among the Six Nations of Grand River, 1899-1939

Race, Gender and Colonialism: Public Life among the Six Nations of Grand River, 1899-1939 by Alison Elizabeth Norman A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theory and Policy Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Alison Norman 2010 Race, Gender and Colonialism: Public Life among the Six Nations of Grand River, 1899-1939 Alison Norman Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theory and Policy Studies Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto 2010 Abstract Six Nations women transformed and maintained power in the Grand River community in the early twentieth century. While no longer matrilineal or matrilocal, and while women no longer had effective political power neither as clan mothers, nor as voters or councillors in the post-1924 elective Council system, women did have authority in the community. During this period, women effected change through various methods that were both new and traditional for Six Nations women. Their work was also similar to non-Native women in Ontario. Education was key to women‘s authority at Grand River. Six Nations women became teachers in great numbers during this period, and had some control over the education of children in their community. Children were taught Anglo-Canadian gender roles; girls were educated to be mothers and homemakers, and boys to be farmers and breadwinners. Children were also taught to be loyal British subjects and to maintain the tradition of alliance with Britain that had been established between the Iroquois and the English in the seventeenth century. -

Brant's Block, Wellington Square

Brant’s Block, Wellington Square Prior to Euro-Canadian settlement on the site that became the City of Burlington, the lands of Halton County were inhabited by Anishnaabe (Ojibway) known as the Mississaugas. The Mississaugas’ traditional territory extended westerly and easterly from Burlington, encompassing what is now the City of Toronto. At that time, Burlington Bay was known by the Mississauga name, Macassa. Shortly after the arrival of Euro- Canadian settlers to the Township of Nelson, Burlington Bay was known as Lake Geneva. Home of Captain Brant at the Head of Lake Ontario (Walsh 1804) Source: Burlington Historical Society At the end of the Revolutionary War, many United Empire Loyalists were given land in the area in return for their loyalty to the Crown. Such was the case for Captain Joseph Brant, a prominent Mohawk and Loyalist, who was granted land in Halton County for his service. Brant selected his desired location at the Head of Lake Ontario. In total, 3,450 acres of land was granted to Brant following its purchase from the Mississaugas in 1795. This transaction is known as the Brant Tract Treaty, Number 3 ¾ (AANDC 2014). The Brant Tract, commonly referred to as Brant’s Block, was patented to Joseph Brant in February of 1798. At that time, the Block was bounded by the Township of Flamborough to the west and Lake Ontario to the south. The northern extent of Brant’s Block was just south of the northern boundary of the First Concession South of Dundas Street and the eastern boundary extended easterly into Lot 18. -

AND the TREATY RELATIONSHIP on the Cover

TREATIES AND THE TREATY RELATIONSHIP On the cover The cover design for this issue began with the Treaty phrase “As long as the sun shines, the grass grows, and the waters flow” represented by three colours (red, green, and blue). These colours were then interwoven to resemble a sweetgrass braid, traditionally signifying mind, body, and spirit, and in this case also representing the three parties in the Treaty relationship (the First Nations, the Crown, and the Creator). The end of the braid includes twenty-one individual strands representing seven past generations, seven future generations, and the Seven Sacred Teachings. The design was a collaboration between artist Kenneth Lavallee and graphic designer Andrew Workman. Contents Gakina Gidagwi’igoomin Anishinaabewiyang: 10 We Are All Treaty People Understanding the spirit and intent of the Treaties matters to all of us. by Karine Duhamel Interpreting the Treaties 16 Historical agreements between the Crown and First Nations are fraught with ambiguity. by Douglas Brown and William Wicken Ties of Kinship 22 The Treaty of Niagara is seen by some as marking the true founding of Canada. by Philip Cote and Nathan Tidridge The Numbered Treaties 26 Western Canada’s Treaties were intended to provide frameworks for respectful coexistence. by Wabi Benais Mistatim Equay (Cynthia Bird) Living Well Together 34 Understanding Treaties as an agreement to share. by Aimée Craft Algonquin Territory 40 Indigenous title to land in the Ottawa Valley is an issue that has yet to be resolved. by Peter Di Gangi Nations in Waiting 46 British Columbia’s First Nations are in a unique situation regarding Treaties.