RGZM – TAGUNGEN Band 30

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

With a Short Neck and Angular Should

LOW HIGH Lot Description Estimate Estimate Chinese archaistic bronze wine vessel (pou), with a short neck and angular shoulder with 1 three ram's head form handles, the body with taotie on a dense ground, raised on a tall foot, 8"h $ 300 - 500 (lot of 2) Chinese archaistic bronzes, the first a pouring vessel on tripod supports with taotie 2 pattern, body with inscription; the other an ox form guang lidded vessel, with a bird motif on the body,10.75"w $ 300 - 500 (lot of 3) Asian bronze items, consisting of a Himalayan ritual dagger (purba) and a ghanta 3 (bell); together with a Chinese archaistic bronze bell, with raised bosses, with wood stand, bell: 8.25"h $ 300 - 500 (lot of 5) Chinese hardstone plaques, consisting of two butterflies; one floral roundel; one 4 fan and one of bird-and-flowers, 2.75"w $ 150 - 250 5 Chinese hardstone bangle, reticulated with bats and tendrils, 2.5"w $ 300 - 500 (lot of 2) Chinese hardstone pebbles, the first carved of a bamboo stalk; the second, of a 6 mouse and sack, largest: 2"w $ 400 - 600 7 (lot of 2) Chinese hardstone figural carvings, featuring one young attendant; and the other of an immortal with a lion on his shoulder, with wood stands, carving: 3.125"h $ 300 - 500 Chinese bronze zoomorph, featuring a recumbent beast with a reticulated body with a bird 8 pattern, 4"w $ 200 - 400 Chinese patinated bronze censer of ding-form, the rim flanked by upright handles and the 9 body cast with floral scrolls, raised on tall tripod supports, with wood stand and lid, censer: 5"h $ 300 - 500 (lot of 5) Chinese -

KIRANJYOT RENU RANA FILE NO. CCRT/SF-3/163/2015 ADDRESS; D 1051 NEW FRIENDS COLONY NEAR MATA MANDIR EMAIL: [email protected] MOBILE: 98101 67661

KIRANJYOT RENU RANA FILE NO. CCRT/SF-3/163/2015 ADDRESS; D 1051 NEW FRIENDS COLONY NEAR MATA MANDIR EMAIL: [email protected] MOBILE: 98101 67661 PROGRESS REPORT 1 WHAT IS SCULPTURE Three-dimensional art that can stand on its own is known as a sculpture. Sculptures vary in sizes, and may be small enough to fit in the palm of a hand or large enough that they can only fit in a large outdoor space. Some sculptures are representative, and may look like a famous person; others may be abstract. The materials used in sculpture vary, and anything from ceramics, cement, recycled materials, paper or synthetics may be used to produce this particular type of art. By definition, a sculpture differs from other structures in that it does not have an intrinsically utilitarian purpose. HISTORY & ORIGIN Sculpture was used mainly as a form of religious art to illustrate the principles of Hinduism, Buddhism, or Jainism. The female nude in particular was used to depict the numerous attributes of the gods, for which it was often endowed with multiples heads and arms. Important milestones in the history of sculpture include: the Buddhist Pillars of Ashokaof the Mauryan period, with their wonderful carved capitals (3rd century BCE); the figurative Greco- Buddhist sculpture of the Gandhara and Mathura schools, and the Hindu art of the Gupta period (1st-6th century CE). In brief, the flow of the growth of sculpture is as follows: Indus Valley Civilization (c.3300-1300 BCE) Mauryan Sculpture: Pillars of Ashoka (3rd Century BC Ajanta Caves (c.200 BCE - 650 CE) Under the Kushans, sculpture from Gandhara and Mathura art went on to influence artists across India, Elephanta Caves (c.550-720) Pallava and Pandya Sculpture from South India (600-900) Ellora Caves (c.600-1000) Chandela Stone Sculpture in Central India (10th-13th century) Chola Bronze Sculpture of South India, Sri Lanka (9th-13th century) Famous Sculptures that impressed and inspired me 1) TheAshoka Pillars 2) SanchiStupa 3) Ajanta Caves 4). -

Of the Grand Cameo: a Holistic Approach to Understanding the Piece, Its Origins and Its Context Constantine Prince Sidamon-Eristoff Sotheby's Institute of Art

Sotheby's Institute of Art Digital Commons @ SIA MA Theses Student Scholarship and Creative Work 2018 The "Whys" of the Grand Cameo: A Holistic Approach to Understanding the Piece, its Origins and its Context Constantine Prince Sidamon-Eristoff Sotheby's Institute of Art Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.sia.edu/stu_theses Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Metal and Jewelry Arts Commons Recommended Citation Sidamon-Eristoff, Constantine Prince, "The "Whys" of the Grand Cameo: A Holistic Approach to Understanding the Piece, its Origins and its Context" (2018). MA Theses. 14. https://digitalcommons.sia.edu/stu_theses/14 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship and Creative Work at Digital Commons @ SIA. It has been accepted for inclusion in MA Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ SIA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The “Whys” of the Grand Cameo: A Holistic Approach to Understanding the Piece, its Origins and its Context by Constantine P. Sidamon-Eristoff A thesis submitted in conformity With the requirements for the Master’s Degree Fine and Decorative Art and Design Sotheby’s Institute of Art 2018 Word Count: 14,998 The “Whys” of the Grand Cameo: A Holistic Approach to Understanding the Piece, its Origins and its Context By: Constantine P. Sidamon-Eristoff The Grand Cameo for France is the largest cameo surviving from antiquity. Scholars have debated who is portrayed on the stone and what its scene means for centuries, often, although not always, limiting their interpretations to this narrow area and typically only discussing other causes in passing. -

^ ^ the Journal Of

^^ The Journal of - Volume 29 No. 5/6 Gemmology January/April 2005 The Gemmological Association and Gem Testing Laboratory of Great Britain Gemmological Association and Gem Testing Laboratory of Great Britain 27 Greville Street, London EC1N 8TN Tel: +44 (0)20 7404 3334 • Fax: +44 (0)20 7404 8843 e-mail: [email protected] • Website: www.gem-a.info President: E A jobbins Vice-Presidents: N W Deeks, R A Howie, D G Kent, R K Mitchell Honorary Fellows: Chen Zhonghui, R A Howie, K Nassau Honorary Life Members: H Bank, D J Callaghan, E A Jobbins, J I Koivula, I Thomson, H Tillander Council: A T Collins - Chairman, S Burgoyne, T M J Davidson, S A Everitt, L Hudson, E A Jobbins, J Monnickendam, M J O'Donoghue, E Stern, P J Wates, V P Watson Members' Audit Committee: A J Allnutt, P Dwyer-Hickey, J Greatwood, B Jackson, L Music, J B Nelson, C H Winter Branch Chairmen: Midlands - G M Green, North East - N R Rose, North West -DM Brady, Scottish - B Jackson, South East - C H Winter, South West - R M Slater Examiners: A J Allnutt MSc PhD FGA, L Bartlett BSc MPhil FGA DCA, Chen Meihua BSc PhD FCA DGA, S Coelho BSc FCA DCA, Prof A T Collins BSc PhD, A G Good FCA DCA, D Gravier FGA, J Greatwood FGA, S Greatwood FGA DCA, G M Green FGA DGA, He Ok Chang FGA DGA, G M Howe FGA DGA, B Jackson FGA DGA, B Jensen BSc (Geol), T A Johne FGA, L Joyner PhD FGA, H Kitawaki FGA CGJ, Li Li Ping FGA DGA, M A Medniuk FGA DGA, T Miyata MSc PhD FGA, M Newton BSc DPhil, C J E Oldershaw BSc (Hons) FGA DGA, H L Plumb BSc FGA DCA, N R Rose FGA DGA, R D Ross BSc FGA DGA, J-C -

Nephrite Imperial Presentation Portrait Snuffbox by Carl Fabergé St

The Orlov-Davydov Nephrite Imperial Presentation portrait snuffbox by Carl Fabergé St. Petersburg. The box was presented on the 26 November 1904 to Count Anatoli Vladimirovich Orlov-Davydov (1837-1905) on his retirement and presented by the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna in the absence of the Emperor at the front. The Orlov-Davydov Imperial Presentation snuffbox by Carl Fabergé St. Petersburg.1904. Nephrite, gold, diamonds. Workmaster: Henrik Wigström. Provenance: Emperor Nicholas II & Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. Count Anatoli Vladimirovich Orlov-Davydov. Wartski, London. The Duchess of Alba. 1 Bibliography. Carl Fabergé - Goldsmith to the Imperial Court of Russia by A. Kenneth Snowman, page 118. Wartski- The First One hundred and Fifty Years by Geoffrey C. Munn, page 248. A highly important Imperial presentation snuffbox, the bun shaped nephrite lid and base mounted with a cage work of green gold laurels and red gold beadwork secured with red gold forget-me-not flowers, tied with similarly coloured gold bows and bearing trefoils set with rose diamonds. The lid is emblazoned with a miniature of Emperor Nicholas II wearing the uniform of the Preobrazhensky Guards by the court miniaturist Vasyli Zuiev, in an elaborate diamond frame surmounted with a diamond-set Romanov crown. Jewelled works of art incorporating the sovereign’s portrait were the highest form of state gift in Imperial Russia. During the reign of Nicholas II Fabergé only supplied fourteen examples to the Emperor and this box is the most lavish of those that survive. Dia. 8.5cm; H. 6cm. The box was presented on 26th September 1904 by Empress Alexandra Feodorovna to Lieutenant-General and Grand Master of the Horse, Count Anatoli Vladimirovich Orlov- Davydov. -

Antique Italian Pietra Dura Brass & Alabaster Comport Dish

anticSwiss 26/09/2021 14:08:10 http://www.anticswiss.com Antique Italian Pietra Dura Brass & Alabaster Comport Dish FOR SALE ANTIQUE DEALER Period: 19° secolo - 1800 Regent Antiques London Style: Altri stili +44 2088099605 447836294074 Height:8cm Width:29cm Depth:29cm Price:700€ DETAILED DESCRIPTION: This is a superb quality antique Italian Pietra Dura mounted, gilt brass and alabaster table-centre comport dish, dating from the late 19th Century. With striking pierced Neo-Gothic chased brass mounts this splendid alabaster dish is set with six highly decorative pietra dura roundels depicting various floral decoration. It is raised on a sturdy circular brass base. It is a sumptuous piece which will make a great statement in any special room. Condition: In really excellent condition, please see photos for confirmation. Dimensions in cm: Height 8 x Width 29 x Depth 29 Dimensions in inches: Height 3.1 x Width 11.4 x Depth 11.4 Pietra dura is a term for the inlay technique of using cut and fitted, highly polished coloured stones to create images. It is considered a decorative art. Pietre dure is an Italian plural meaning "hard rocks" or hardstones; the singular pietra dura is also encountered in Italian. In Italian, but not in English, the term embraces all gem engraving and hardstone carving, which is the artistic carving of three-dimensional objects in semi-precious stone, normally from a single piece, for example in Chinese jade. The traditional convention in English has been to use the singular pietra dura just to denote multi-colored inlay work. However, in recent years there has been a trend to use pietre dure as a term for the same thing, but not for all of the techniques it covers, in Italian. -

Lot Description LOW Estimate HIGH Estimate 4000 a Wooden Vessel

LOW HIGH Lot Description Estimate Estimate A wooden vessel with a hardstone ring handle, carved with Indian deities, 5.5"W 4000 x 19"H $ 100 - 200 4001 A blue and white Chinese vase depicting scholar and servant, 6.5"W x 12.5"H $ 200 - 300 A Chinese blue and white revolving vase, with pair of mystical beast handles , six- 4002 character mark to the base; 5.5"w x 8.75"h $ 300 - 500 A Chinese blue and white footed bowl decorated with dragon chasing flaming 4003 pearls and elephant head handles , 10.5"W x 12"H $ 200 - 300 4004 A Tang-style Sancai ewer in a phoenix head shape; 4.5"W x 9.75"H $ 100 - 200 A pair of Chinese double gourd Familie-rose vases, enameled with floral 4005 decoration on a green ground, 8.5"W x 14"H $ 500 - 700 Chinese Guan-type ceramic brush washer, of drum form with two rows of raised 4006 bosses accenting the side, the blue-gray glaze suffused with a network of dark crackles, 6"W x 2.75"H $ 500 - 700 A Chinese hardstone carving of a covered antique vase surrounded with four 4007 dragons 9"H x 6"W $ 150 - 250 A Chinese wooden ruyi scepter inset with three carved jade panels 19.5"W x 4008 3.25"H $ 500 - 700 A Chinese wooden ruyi scepter, with "longevity" incised in the central panel, 4009 14.5"W x 4.5"H $ 150 - 250 4010 (lot of 6) A group of six Southeast Asian dishes and wares, 8"W x 1.5"H $ 100 - 200 4011 A large Chinese celadon bowl with incised decorative patterns, 13"W x 6"H $ 200 - 300 A large Chinese yellow ground bowl with incised patterns of dragon and cloud 4012 scrolls, 13.5"W x 5.75"H $ 200 - 300 4013 A -

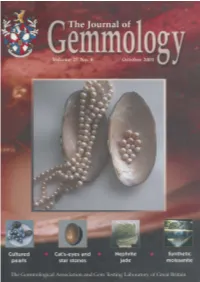

X"^ the Journal of "I Y Volume 27 No

GAGTL EDU GemmolosX"^ The Journal of "I y Volume 27 No. 8 October 2001 tj J Cultured Cat's-eyes and Nephrite Synthetic pearls star stones jade moissanite The Gemmological Association and Gem Testing Laboratory of Great Britain Gemmological Association and Gem Testing Laboratory of Great Britain 27 Greville Street, London EC1N 8TN Tel: 020 7404 3334 Fax: 020 7404 8843 e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.gagtl.ac.uk President: Professor A.T. Collins Vice-Presidents: A.E. Farn, R.A. Howie, D.G. Kent, R.K. Mitchell Honorary Fellows: Chen Zhonghui, R.A. Howie, R.T. Liddicoat Jnr, K. Nassau Honorary Life Members: H. Bank, D.J. Callaghan, E.A. Jobbins, H. Tillander Council of Management: T.J. Davidson, R.R. Harding, I. Mercer, J. Monnickendam, M.J. O'Donoghue, E. Stern, I. Thomson, J-P. van Doren, V.P. Watson Members' Council: A.J. Allnutt, S. Burgoyne, P. Dwyer-Hickey, S.A. Everitt, J. Greatwood, B. Jackson, L. Music, J.B. Nelson, P.G. Read, P.J. Wates, C.H. Winter Branch Chairmen: Midlands - G.M. Green, North West - I. Knight, Scottish - B. Jackson, South West - R.M. Slater Examiners: A.J. Allnutt, M.Sc, Ph.D., FGA, L. Bartlett, B.Sc, M.Phil., FGA, DGA, S. Coelho, B.Sc, FGA, DGA, Prof. A.T. Collins, B.Sc, Ph.D, A.G. Good, FGA, DGA, J. Greatwood, FGA, G.M. Howe, FGA, DGA, S. Hue Williams MA, FGA, DGA, B. Jackson, FGA, DGA, G.H. Jones, B.Sc, Ph.D., FGA, Li Li Ping, FGA, DGA, M. -

Antique Grand Tour Pietra Dura Plaque Giltwood Frame 19Th C

anticSwiss 01/10/2021 16:29:36 http://www.anticswiss.com Antique Grand Tour Pietra Dura Plaque Giltwood Frame 19th C FOR SALE ANTIQUE DEALER Period: 19° secolo - 1800 Regent Antiques London Style: Altri stili +44 2088099605 447836294074 Height:41cm Width:32cm Depth:4cm Price:1650€ DETAILED DESCRIPTION: This is an exceptional Italian antique Grand Tour Pietra Dura plaque set in a stunning Florentine hand-carved giltwood frame, dating from the late 19th century. This stunning Pietra Dura plaque is of rectangular shape and was made with superb skill and artistry from many different hand-carved semi-precious stones. It features a joyful scene of a man and woman dancing in Tyrolean style costumes in front of their house. The scene is captured in very high detail and the inlaid decoration in the various specimen hardstones is of the highest quality. The plaque is framed in its original hand-carved giltwood frame. Add this beautiful antique Pietra Dura plaque to a special wall in your home. Condition: It is in really excellent condition and is a delightful scene which will grace any room in your home. Dimensions in cm: Height 41 x Width 32 x Depth 4 Dimensions in inches: Height 16.1 x Width 12.6 x Depth 1.6 Pietra dura is a term for the inlay technique of using cut and fitted, highly polished coloured stones to create images. It is considered a decorative art. Pietre dure is an Italian plural meaning "hard rocks" or hardstones; the singular pietra dura is also encountered in Italian. In Italian, but not in English, the term embraces all gem engraving and hardstone carving, which is the artistic carving of three-dimensional 1 / 4 anticSwiss 01/10/2021 16:29:36 http://www.anticswiss.com objects in semi-precious stone, normally from a single piece, for example in Chinese jade. -

American, 20Th Century

LOW HIGH Lot Description Estimate Estimate Jill Davenport (American, 20th Century), "Green Boots with Hat," oil on canvas, signed lower 1 right, titled verso, overall (with frame): 25"h x 32"w $ 100 - 200 Jill Davenport (American, 20th Century), Cows in the Pasture, oil on canvas, unsigned, 2 canvas (unframed): 25"h x 32"w $ 100 - 200 Jill Davenport (American, 20th century), "Person with Pig," oil on canvas, initialed and titled 3 verso, canvas (unframed): 26"h x 38"w $ 100 - 200 Jill Davenport (American, 20th Century), "Attic Series: Clean Shirt," 1984, oil on canvas, 4 signed lower right, gallery label (J. Noblett, Sonoma, CA) with title and date affixed verso, overall (with frame): 20.5"h x 25"w $ 100 - 200 Russian School (19th century), Merchant in the Snow, 1997, oil on canvas, signed in Cyrillic 5 and dated lower right, overall (with frame): 28.5"h x 32.5"w $ 50 - 100 Portrait of a Musician, charcoal on paper, signed indistinctly lower right, 20th century, 6 overall (with frame): 32"h x 26"w $ 200 - 400 7 Minerva Bernetta (Kohlhepp) Teichert (American, 1889-1976), Portrait of a Lady in Red, oil on panel, signed lower right, panel: 24"h x 13"w, overall (with frame): 28"h x 17.5"w $ 600 - 900 American School (20th Century), Girl making pottery, oil on canvas, partial signature lower 8 right, overall (with frame): 30"h x 35.5"w $ 300 - 500 Follower of David Park (American, 1911-1960), Portrait of a Lady, oil on canvas, unsigned, 9 overall (with frame): 19.25"h x 15.25"w $ 200 - 400 10 American School (19th century), Portrait of a Gentleman, -

Lapidary Works of Art, Gemstones, Minerals And

MINERALS AND NATURAL HISTORY MINERALS AND NATURAL May 16, 2018 Wednesday Los Angeles LAPIDARY WORKS OF ART, GEMSTONES, WORKS OF ART, LAPIDARY LAPIDARY WORKS OF ART, GEMSTONES, MINERALS AND NATURAL HISTORY | Los Angeles, Wednesday May 16, 2018 24619 LAPIDARY WORKS OF ART, GEMSTONES, MINERALS AND NATURAL HISTORY Wednesday May 16, 2018 at 10am Los Angeles BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES ILLUSTRATIONS 7601 W. Sunset Boulevard +1 (323) 850 7500 Claudia Florian, G.J.G Front cover: Lot 4170 Los Angeles, California 90046 +1 (323) 850 6090 fax Co-Consulting Director Inside front cover: Lot 4287 bonhams.com (323) 436-5437 Session page: Lot 4020 To bid via the internet please visit [email protected] Inside back cover: Lot 4464 PREVIEW www.bonhams.com/24619 Back cover: Lot 4463 Friday, May 11, 12-5pm Tom E. Lindgren Saturday, May 12, 12-5pm Please note that telephone bids Co-consulting Director Sunday, May 13, 12-5pm must be submitted no later (323) 436-5437 Monday, May 14, 10-5pm than 4pm on the day prior to [email protected] Tuesday, May 15, 10-5pm the auction. New bidders must also provide proof of identity Katherine Miller SALE NUMBER: 24619 and address when submitting Business Administrator Lots 4001 - 4473 bids. Telephone bidding is only (323) 436-5445 available for lots with a low [email protected] CATALOG: $35 estimate in excess of $1000. Please contact client services with any bidding inquiries. Please see pages 178 to 181 for bidder information including Conditions of Sale, after-sale collection and shipment. Bonhams 220 San Bruno Avenue San Francisco, California 94103 © 2018, Bonhams & Butterfields Auctioneers Corp.; All rights reserved. -

Exploring Natural Stone and Building a National Identity

arts Article Exploring Natural Stone and Building a National Identity: The Geological Exploration of Natural Stone Deposits in the Nordic Countries and the Development of a National-Romantic Architecture Atli Magnus Seelow Chalmers University of Technology, Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering, Sven Hultins Gata 6, Gothenburg 41296, Sweden; [email protected]; Tel.: +46-72-968-88-85 Academic Editor: Marco Sosa Received: 22 February 2017; Accepted: 2 May 2017; Published: 12 May 2017 Abstract: In the second half of the 19th century, new methods for quarrying and processing natural stone were developed. In the Nordic countries Sweden, Norway, and Finland, this technological progress went hand in hand with a systematic geological mapping and large-scale exploitation of natural stone deposits. As a result, new constructions were developed, changing the building practice in these countries. With the end of historicism, a new architecture arose that, particularly in Norway and Finland, acquired a national-romantic character. This paper examines the interaction between geological exploration, commercial development, technical inventions, and the development of national-romantic architecture. Keywords: architecture; 19th century; 20th century; Nordic countries; natural stone; national romanticism; geology 1. Introduction In the second half of the nineteenth century, the methods for quarrying and processing natural stone were developed tremendously—parallel to the industrialization of brick production and later the advent of concrete construction. A number of technical innovations, such as the invention of the band saw or the use of power machines and explosives from the 1860s and 1880s onwards respectively, facilitated the hitherto laborious quarrying of natural stone, especially of hard rock varieties (Elliott 1992, pp.