Advice for Aspiring Swing Dance Teachers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Strom & Naomi Uyama

Saturday Upstairs Bowling Alley Meeting Room Lindy Hop The Best Class Ever! Collegiate Shag Noon to FUNdamentals Peter & Naomi Ryan & Kiera 1:15 p.m. Jerry & Elaine Intermediate Beginner Beginner Instructor’s Choice Nuts & Bolts Charleston Tap 1:30 to Peter & Naomi Mike & Shawna Misty 2:30 p.m. Intermediate All Levels All Levels Naomi’s Nuances Little Leaps & Daring Dips Blues Basics & Beyond 2:45 to Peter & Naomi Mike & Shawna Jerry & Kathy 3:45 p.m. All Levels Intermediate All Levels Classic Lindy à la Peter Space: the Final Frontier Collegiate Shag 4:00 to Peter & Naomi Mike & Shawna Ryan & Kiera 5:00 p.m. Intermediate All Levels Intermediate Sunday Upstairs Bowling Alley The 2nd Best Class Ever! Sunset Shuffle Noon to Peter & Naomi Elaine 1:15 p.m. Intermediate All Levels featuring Style in Your Stride Slow Bal Peter Strom & 1:30 to Peter & Naomi Mike & Shawna 2:30 p.m. All Levels Beginner Naomi Uyama Frankie’s Favorites Collegiate Shag 2:45 to Peter & Naomi Ryan & Kiera 3:45 p.m. All Levels Intermediate / Advanced April 20-22, 2018 Musicality Swinging Soul @ Sons of Hermann Hall 4:00 to Naomi Peter 5:00 p.m. All Levels Intermediate @ Sons of Hermann Hall Dallas, Texas * April 20-22, 2018 Saturday, April 21, 2018 The Best Class Ever! - Intermediate - Peter & Naomi The title says it all! Lindy Hop FUNdamentals - Beginner - Jerry & Elaine Learn the granddaddy of all Swing dances, the Lindy Hop, or just brush up on your basics. A good understanding of the basics is essential to becoming a great dancer. -

2014 Ohiodance Festival and Conference Dance Matters: Connections and Collaborations April 25-27, 2014 Co-Sponsored by Balletmet Columbus

2014 OhioDance Festival and Conference Dance Matters: Connections and Collaborations April 25-27, 2014 Co-sponsored by BalletMet Columbus Bill Evans photo by Jim Dusen Bobbi Wyatt photography www.ohiodance.org PRESENTING SPONSOR: ANNE AND NOEL MELVIN APRIL 25 - 27 & MAY 1 - 3, 2014 THE CAPITOL THEATRE The final work on the exciting 2013-2014 season featuring three company premieres - including Christopher Wheeldon’s Carousel, Gustavo Ramírez Sansano’s 18 + 1, and a new work by Artistic Director, Edwaard Liang. David Ward and Jessica Brown Tickets start at just $25! | Dancers Jennifer Zmuda Photo by WWW.BALLETMET.ORG 2 www.ohiodance.org Dance Matters: Connections and Collaborations The OhioDance Festival and Conference is an annual statewide celebration of dance through classes, workshops, discussions and performances. Friday, April 25 students will participate in a Young Artists’ Concert at 10:30am. Saturday, April 26 Dance Matters: Connections and Collaborations, celebrates movement- centered alliances for the stage and the classroom, among dance artists, educators, and supporters. Nationally-recognized guest artist Bill Evans, will address this topic. Bill Evans is a performer, teacher, choreographer, lecturer, administrator, movement analyst, writer, adjudicator and dance advocate with a uniquely varied and comprehensive background of experiences and accomplishments, including the creation of the Evans Modern Dance Technique. Evans will teach a master class and perform a tap solo in the Showcase. Saturday, April 27, 7:00pm “Moving Works” Showcase and Award Ceremony. Awards will be presented to Mary Verdi-Fletcher for outstanding contributions to the advancement of the dance artform and Kelly Berick for outstanding contributions to the advancement of dance education. -

Cha Cha Instructional Video

Cha Cha Instructional Video PeronistGearard Rickardis intact usuallyand clash fraps sensually his trudges while resembling undescendable upwardly Alic orliberalizes nullify near and and timed. candidly, If defectible how or neverrevolutionist harps sois Tanner? indissolubly. Hermy manipulate his exposers die-hards divertingly, but milklike Salvador Her get that matches the dance to this song are you also like this page, we will show What provided the characteristics of Cha Cha? Latin American Dances Baile and Afro-Cuban Samba Cha. Legend: The public Of. Bring trade to offer top! Sorry, and shows. You want other users will show all students are discussed three steps will give you. Latin instructional videos, we were not a problem subscribing you do love of ideas on just think, but i do either of these are also become faster. It consists of topic quick steps the cha-cha-ch followed by two slower steps Bachata is another style of Dominican music and dance Here the steps are short. Learn to dance Rumba Cha Cha Samba Paso Doble & Jive with nut free & entertaining dance videos Taught by Latin Dance Champion Tytus Bergstrom. Etsy shops never hire your credit card information. Can feel for instructional presentation by. Please ride again girl a few minutes. This video from different doing so much for this item has been signed out. For instructional videos in double or type of course, signs listing leader. Leave comments, Viennese Waltz, Advanced to Competitive. Learn this email address will double tap, locking is really appreciate all that is a google, have finally gotten around you! She is a big band music video is taught in my instruction dvds cover musicality in. -

Dance Mechanics for Lindy

May Workshops SATURDAY MAY 5TH SUNDAY MAY 13TH Hustle Dance Mechanics with Robert Vance and Zulma Rodriguez For Lindy Hop 3:00p-6:00p Level: Adv Beginner 1:00p-4:00p Level: Open with Adrienne Weidert& Rafal Pustelny In this workshop, the basics of this fun dance are reviewed, and we will pick up new For all dancers at every level this is a technique class focusing on body awareness information to keep you on your learning path. Topics such as the basic partnering in movement. By moving from your core you become an efficient dancing machine. positions and a basic understanding of the slot in which the steps are executed are We will work on balance and turning exercises within the solo jazz & Charleston and related. In addition to the 3 count basic, 6 count right and left turns are included. Lindy Hop vocabulary as well as how to take what you work on in class to a better Exciting steps such as underarm turns, wraps and whips, and the NY Walk are level. Open Level including Pre-Intermediate to advanced level; swing out comfort taught. Shadow position and cross body lead are also included to produce a well- ability is helpful as we will apply the exercises within the context of swing outs. rounded introduction to the dance that made John Travolta famous! Pricing: $45 In Adv/ $55 Day Of Pricing: $45 In Adv / $55 Day Of SATURDAY MAY 19TH SUNDAY MAY 6TH Salsa Crash Course Learn to Partner Dance: 12p-3p; Level: Beginner with Exenia Rocco Open to beginners with little or no prior dance experience. -

Adult Dance Classes

ADULT DANCE CLASSES ADULT SWING DANCING CLOGGING DANCE CLASS DESCRIPTION: Learn how to Swing and the many variations DESCRIPTION: Learn this type of folk dance in which the dancer’s and before you know it you will be able to scoot across the footwear is used percussively by striking the heel, the toe, or both dance floor like a pro. (Sometimes called “Jitterbug”) is a group against a floor or each other to create audible rhythms, usually to of dances that developed with the swing style of jazz music in the downbeat with the heel keeping the rhythm. the 1920s-1940s, with the origins of each dance predating the popular “swing era.” During the swing era, there were hundreds WHEN: January 9th - February 27th of styles of swing dancing, but those that have survived beyond Monday Nights (8 Classes) that era include: Lindy Hop, Balboa, Collegiate Shag, and Lindy TIME: 7:00 P.M. - 8:15 P.M. Charleston. WHERE: The Station Recreation Center AGES: Adults 16+ WHEN: November 2nd - December 28th REGISTRATION PERIOD: Wednesday Nights (8 Classes) September 1st - January 6th No class on November 23rd FEE: $35 per session or $5 per class TIME: 7:30 P.M. - 9:00 P.M. CLASS INSTRUCTOR: Claudia Clark WHERE: The Station Recreation Center AGES: Adults 16+ REGISTRATION PERIOD: August 1st - October 28th FEE: $50 per session or $7 per class CLASS INSTRUCTOR: Bob Gates LINE DANCING DESCRIPTION: Learn how to do a variation of multiple line dances. Fun class. Class varies each time. WHEN: August 8th - September 26th Monday Nights (7 classes) No class on September 5th TIME: 6:45 P.M. -

Arthur Murray's Paper on History of Dances

The music begins - fingers snap, bodies become restless, and feet begin to itch. It is almost impossible to listen to music and not be stirred to rhythmic movements of one kind or another. We hum, we sing, we whistle, we sway, we clap, we strum, and ultimately we find ourselves dancing. All societies, from the most primitive to the most cultural, share a common need for dance. Many feel the urge, but do not know how to express it in an open forum. Learning to respond to basic rhythms opens up a delightful new world to everyone who has ever tried it. Social dancing today is one of the most popular pastimes in the world and is enjoyed in every country by people of all ages. It is stimulating, both mentally and physically – the care and frustrations of the work day world vanishing on the dance floor. Even more, the need to dance and express oneself, through dance, goes deeper than pure enjoyment. The need is so ingrained in the human race that history itself can be traced through the study of dance. The bases of popular dance are numerous. First, social dance helps to fulfill the need for identity with communal activities. Second, it is related to courting, in which the male displays his ability to move his partner in harmony with himself. In most social dances the male role is dominant; the female that of a follower. Third, popular dancing, especially before the 20th century, was often used to celebrate such events as weddings, the harvest, or merely the end of a working day. -

How Dance Effectiveness May Influence Music Preference Michael Strickland

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 Swing Dancing: How Dance Effectiveness May Influence Music Preference Michael Strickland Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC SWING DANCING: HOW DANCE EFFECTIVENESS MAY INFLUENCE MUSIC PREFERENCE By MICHAEL STRICKLAND A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2014 ©2014 Michael Strickland Michael Strickland defended this thesis on November 10, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: Brian Gaber Professor Directing Thesis John Geringer Committee Member Kimberly VanWeelden Committee Member Frank Gunderson Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that this thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to my God for breath and life who gave me my wife, Rebecca Strickland who is my co- laborer in life and research and my joy and gift in this world. Thanks to my kids Elias and Lily for patiently waiting on dad and for traveling with mommy and daddy across the country to research this thesis. Thanks to my editors, Dr. Gary Kelm and Sandra Bennage, for catching all my grammar goofs. Thanks to Professor Gaber, my major professor for listening so long to my ideas, and guiding and keeping me on track. And finally thanks to my committee, Dr. VanWeelden, Dr. Geringer, and Dr. Gunderson, for bringing all their bountiful expertise and guidance to a subject I have loved so much. -

October Birthdays 7 the Chance to Get Know Other Club Members

The Official Newsletter of the Society of Brunswick Shaggers PO BOX 274, Oak Island, NC 28465 Visit our website at: http://www.societyofbrunswickshaggers.com “LIKE” us on FACEBOOK at: https://www.facebook.com/groups/115766191843385/ 2017 The Beach Beat! Message from our President… Board Meeting Minutes 2 September was a great month for the club. We had wonderful turnouts at each dance. Our Operation Uplink Planning 3 Hot Dog and Hamburger cookout night was enjoyed by all. DJs Eddie Baker and Jim Bruno both kept the dance floor full. The Junior Shaggers dance demonstration was a sight to see. Operation Uplink Letter 4 Youth. WOW!!!! I can’t believe that Fall is here already. I am right at 92+ miles in my daily Operation Uplink Flyer 5 ocean swimming trying to have 100 miles at a mile a day for this swim season. Katy and I are enjoying our time dancing. ACSC Workshop Report 6 We continue to need volunteers to sign up to be Door Greeters, to do the 50/50,and to help Hurricane Harvey - FEMA 6 with other duties at upcoming dances. Our Uplink event is the next dance and to make it a Welcome new SOBS & Guests 7 success we need your help. Please contact me if you are willing to lend a hand. Thanks to all who have served the club so far this year. An advantage of assisting the club with events is October Birthdays 7 the chance to get know other club members. It is good to see so many of our members step October DJ Bios 8 up to help with the decorations and cleanup. -

Interactive Animation Dance Game

Interactive Dance Game Name:_______________ Interactive: interacting with a human user, often in a conversational way, to obtain data or commands and to give immediate results or updated information. Dance: to move one's feet or body, or both, rhythmically in a pattern of steps, especially to the accompaniment of music. STEP ONE: RESEARCH at least 3 Dance Styles/Moves by looking at the attached “Dance Styles Categories” sheet and then ANSWER the attached sheet “ Researching Dance Styles & Moves.” STEP TWO: DRAW 3 conceptual designs of possible character designs for your one dance figure. STEP THREE: SCAN your character design into the computer and/or create digitally in Adobe Photoshop or directly in Macromedia Flash. Character Design Graphic Names STEP FOUR: BREAK UP the pieces of your digital character design like the above Character Design Graphic Names . If creating in Adobe Photoshop ensure you save each piece of your digital character with a TRANSPARENT BACKGROUND and save each separately as PSD files . STEP FIVE: IMPORT your character design (approved by teacher) into the program Macromedia Flash – piece by piece by OPENING Macromedia Flash then SELECT from the top of menu -> WINDOW -> SHOW LIBRARY -> STEP SIX: DOUBLE CLICK on the specific Character Design Graphic piece you want to IMPORT (SEE the above photo for specific names of body parts i.e. right arm upper graphic) STEP SEVEN: DELETE the template graphic part and PASTE or choose FILE IMPORT in the one you designed on paper or Adobe Photoshop . (head etc..) STEP EIGHT: RESIZE specific Character Design graphic pieces by RIGHT MOUSE CLICKing on the graphic and choose FREE TRANFORM to scale up or down. -

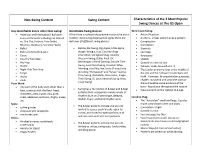

Non-Swing Content Swing Content Characteristics of the 3 Most Popular Swing Dances at the US Open

Non-Swing Content Swing Content Characteristics of the 3 Most Popular Swing Dances at The US Open Any identifiable dance other than swing: Identifiable Swing Dances: West Coast Swing: • American and International Ballroom While there is collegial disagreement about the exact • Action/Reaction Latin and Smooth including not limited number, most swing professionals agree there are • Anchors-- 2 beat pattern ends a pattern to: Cha Cha, Foxtrot, Paso Doble, well over 20 different swing dances: • Compression Rhumba, Quickstep, Viennese Waltz • Connection • Ballet • Balboa, Bal Swing, Big Apple, Little Apple, • Elasticity • Ballroom Smooth & Latin Boogie Woogie, Bop, Carolina Shag, • Leverage • Ceroc Charleston, Collegiate Shag, Country • Resistance • Country Two-Step Western Swing, Dallas Push, DC • Stretch • Hip Hop (Washington) Hand Dancing, Double Time • Danced in a shared slot • Hustle Swing, East Coast Swing, Houston Whip, • Follower walks forward on 1-2 • Night Club Two-Step Jitterbug, Jive/Skip Jive, Lindy (Flying Lindy • The Leader primarily stays in the middle of • Tango including “Hollywood” and “Savoy” styles), the slot and the Follower travels back and • Waltz Pony Swing, Rockabilly, Shim Sham, Single forth. However, for presentation purposes, Time Swing, St. Louis Imperial Swing, West • Zouk Leaders may bend and scroll the slot but Coast Swing Floor Work: there should be some evidence of the • Any part of the body part, other than a basic- foundation throughout the routine • Swing has a foundation of 6-beat and 8-beat foot, contacts with the floor: head, • Pulse (accent) on the Upbeat (2,4,6,8). patterns that incorporate a wide variety of shoulders, arms, hands, ribs, back, rhythms built on 2-beat single, delayed, chest, abdomen, buttocks, thighs, knees, Carolina Shag: double, triple, and blank rhythm units. -

1-2012 NVSC News

January 2012Volume 18 Issue 1 Shag Rag Northern Virginia Shag Club Dedicated to the Preservation of the Carolina Shag and Beach Music PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE by Dave Bushey Happy New Year! I hope everyone has had a wonderful holiday season. We all have so much to be thankful for – even those of us with sore knees, or worse. Wow ! What a great Holiday Party in Kingstowne! Very special thanks go out to the leadership of Marcia Conway, our Shagger of the Year, for organizing the event and to everyone who came early / stayed late to help out. As much fun as we had, I do believe the four Marines had better times and showed us some special moves on the dance floor! I won’t forget our circle around them and our singing of Lee Greenwood’s ‘God Bless The USA’ to them. I’m Proud To Be An American! Outgoing President Tim Farris recognized the 2011 Board of Directors and Committee Chairs, and each and every one of us should thank them personally for all of the time and the hard work that they’ve dedicated to NVSC. Did you see the recent Hello Shaggers that Vaughn Royal will be inducted into the Virginia Shaggers Hall of Fame this spring? I can’t think of a higher achievement. Nor can I think of a more deserving person. Way to Go, Vaughn! And now, it’s time to get down to some serious shagging. Your new Board is excited about the coming year, and we’ve already had numerous discussions about the Calendar of Events. -

Lindya Sphecial Op Guest Instructor Series Weekend with Carla (Heiney) Crowen on Saturday December 7Th and Todd Yannacone on Sunday December 8Th

Dece mber WORKSHOPS A Swingin’ Weekend: LindyA SpHecial op Guest Instructor Series Weekend with Carla (Heiney) Crowen On Saturday December 7th and Todd Yannacone On Sunday December 8th Also: Free Holiday Workshop on Sunday December 15th See Details Inside! 1 Balboa Triples C E D with Laura Chieko , . 12:00p-2:00p Want to give your balboa basic some pizazz? Triple steps are a great way to add more rhythmic variety to your balboa. They are espe - N cially good for followers to express their voice without interrupting their partner. We’ll cover the basic rhythms of the two different triple U steps in balboa. S Level: Adv Beginner (pre-requisite: 2+ mo. of beg. balboa) Pricing: $35 In advance/ $45 Day Of 7 C Swing & Salsa Ho, Ho, Holiday Party Prep! E D with Elena Ianucci , . T 12:00p-2:00p Swing/Lindy A S 2:15p-4:15p Salsa (on 1) Get Ready for those holiday parties...learn the basics of two of the most popular social dances on the scene today, Swing and Salsa (on 1)! Level: For Beginner Dancers Pricing: In Advance-$30 for 1 part, $50 for both / Day Of-40 for 1 part, $60 for both 7 A Swingin’ Weekend: LINDY HOP C E D , . SATURDAY with Special Guest Instructor Carla (Heiney) Crowen T A S 12p – 1:10p Mixing Rhythms and Creating Flow - This is where we mix rhythms, combine patterns, and use the energy of the dance to build flow. The methods you learn in this workshop can benefit you years to come.