Critical Spatial Practice As Parrhesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Does It Mean to Make-Up the Mind (Οὕτω Διανοεῖσθε)? Justin Murphy

parrhesia 29 · 2018 · 163-189 what does it mean to make-up the mind (οὕτω διανοεῖσθε)? justin murphy Under what conditions can thought and speech participate meaningfully in sys- temic political transformations? In my view, two bodies of late twentieth-century thought stand out as the most advanced efforts to answer this question. Gilles De- leuze and Michel Foucault, in their own registers and of course with very differ- ent accents, both suggest substantial but complicated roles thinking and speaking might have to play in any viable future project of emancipatory politics. Given the idealistic associations and connotations of such terms as thinking and speaking, it is no surprise that both figures have been charged with similar crimes: individual- ism, aestheticism, or escapism, all of which are typically implied to render their bodies of work unhelpful for projects of organized, collective political change.1 In the present historical moment of the so-called age of information, we are now in a better position than ever to understand the ways in which mere thought and speech are unable to generate politically significant emancipatory dynamics. In modern global capitalism, it has never seemed more clear that what is called free- dom of speech and the public exchange of ideas is perfectly consistent with the perpetuity and even intensification of oppressive institutional dynamics. Yet, I wish to suggest that in this rightful disillusionment with mere thought and speech lies an opportunity for improving our understanding of the unique conditions under which certain types of thought and speech might be keys to unlocking new forms of emancipatory politics today, in the context of what Deleuze called “con- trol societies.”2 If it is true that Foucault and Deleuze are two of the most advanced thinkers of this question—and yet even they remain uncleared of charges relating to political triviality—then it would seem that the surest way to advance the question would be to begin at the edges of where they left off. -

Critical Inquiry As Virtuous Truth-Telling: Implications of Phronesis and Parrhesia ______

______________________________________________________________________________ Critical Inquiry as Virtuous Truth-Telling: Implications of Phronesis and Parrhesia ______________________________________________________________________________ Austin Pickup, Aurora University Abstract This article examines critical inquiry and truth-telling from the perspective of two comple- mentary theoretical frameworks. First, Aristotelian phronesis, or practical wisdom, offers a framework for truth that is oriented toward ethical deliberation while recognizing the contingency of practical application. Second, Foucauldian parrhesia calls for an engaged sense of truth-telling that requires risk from the inquirer while grounding truth in the com- plexity of human discourse. Taken together, phronesis and parrhesia orient inquirers to- ward intentional truth-telling practices that resist simplistic renderings of criticality and overly technical understandings of research. This article argues that truly critical inquiry must spring from the perspectives of phronesis and parrhesia, providing research projects that aim at virtuous truth-telling over technical veracity with the hope of contributing to ethical discourse and social praxis. Keywords: phronesis, praxis, parrhesia, critical inquiry, truth-telling Introduction The theme of this special issue considers the nature of critical inquiry, specifically methodological work that remains committed to explicit goals of social justice and the good. One of the central concerns of this issue is that critical studies have lost much of their meaning due to a proliferation of the term critical in educational scholarship. As noted in the introduction to this issue, much contemporary work in education research that claims to be critical may be so in name only, offering but methodological techniques to engage in critical work; techniques that are incapable of inter- vening in both the epistemological and ontological formations of normative practices in education. -

Exploring Liquid Modernity, Material Feminisms, Care of the Self, and Parrhesia

Journal of critical Thought and Praxis Iowa state university digital press & School of education ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Volume 6 Issue 1 Everyday Practices of Social Justice Article 2 Working Towards Everyday Social Justice Action: Exploring Liquid Modernity, Material Feminism, Care of the Self, and Parrhesia Lauren P. Hoffman Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/jctp/vol6/iss1/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Repository @ Iowa State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Critical Thought and Praxis by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Iowa State University Journal of Critical Thought and Praxis 2017, Vol. 6, No. 1, 1-17 Working Towards Everyday Social Justice Action: Exploring Liquid Modernity, Material Feminisms, Care of the Self, and Parrhesia Lauren P. Hoffman* Lewis University The purpose of this paper is to explore the difficulty many critically prepared educators and leaders experience when wanting to translate their social justice knowledge into everyday social justice practices. Even though these individuals are critically conscious and want to critically act, many become overwhelmed with the enormity of the neoliberal crisis, tend to fear actually acting against or speaking up in the face of injustice, and may become cynical in terms of even believing in the possibility of any type of educational and social transformation. To address this reticence, the postmodern and posthuman concepts of liquid modernity (Bauman, 2006, 2007) material feminisms (Barad, 2007,2008), care of the self and parrhesia (Foucault, 2001, 2005, 2011) were presented to educational leadership doctoral students as ideas to explicitly challenge their issues of fear and cynicism. -

Parrhesia 31 · 2019 Parrhesia 31 · 2019 · 1-16

parrhesia 31 · 2019 parrhesia 31 · 2019 · 1-16 gaston bachelard and contemporary philosophy massimiliano simons, jonas rutgeerts, anneleen masschelein and paul cortois1 There are philosophers whose name sounds familiar, but who very few people know in more than a vague sense. And there are philosophers whose footprints are all over the recent history of philosophy, but who themselves have retreated somewhat in the background. Gaston Bachelard (1884-1962) is a bit of both. With- out doubt, he was one of the most prominent French philosophers in the first half of the 20th century, who wrote over twenty books, covering domains as diverse as philosophy of science, poetry, art and metaphysics. His ideas profoundly influ- enced a wide array of authors including Georges Canguilhem, Gilbert Simondon, Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, Bruno Latour and Pierre Bourdieu. Up until the 1980s, Bachelard’s work was widely read by philosophers, scientists, literary theo- rists, artists, and even wider audiences and in his public appearances he incar- nated one of the most iconic and fascinating icons of a philosopher. And yet, surprisingly, in recent years the interest in Bachelard’s theoretical oeuvre seems to have somewhat waned. Apart from some recent attempts to revive his thinking, the philosopher’s oeuvre is rarely discussed outside specialist circles, often only available for those able to read French.2 In contemporary Anglo-Saxon philosophy the legacy of Bachelard seems to consist mainly in his widely known book Poetics of Space. While some of Bachelard’s contemporaries, like Georges Canguilhem or Gilbert Simondon (see Parrhesia, issue 7), who were profoundly influenced by Bachelard, have been rediscovered, the same has not happened for Bachelard’s philosophical oeuvre. -

Kierkegaard on Socrates' Daimonion

Kierkegaard on Socrates’ daimonion Citation for published version (APA): Sneller, R. (2020). Kierkegaard on Socrates’ daimonion. International Journal of Philosophy and Theology, 81(1), 87-100. https://doi.org/10.1080/21692327.2019.1649602 DOI: 10.1080/21692327.2019.1649602 Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2020 Document Version: Publisher’s PDF, also known as Version of Record (includes final page, issue and volume numbers) Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

Parrhesia E Injusticias Epistémicas

Parrhesia and epistemic injustices Parrhesia e injusticias epistémicas Gonzalo Lucas Gallego Universidad de Murcia [email protected] DOI: https://doi.org/10.15366/bp2017.17.015 Bajo Palabra. II Época. Nº17. 2017. Pgs: 309-328 Recibido: 15/01/2016 Aprobado: 26/10/2017 Resumen Abstract El presente trabajo acomete el aná- The present paper attempts to analyse lisis de las complejas relaciones entre the complex relationship between truth verdad y democracia a partir de la no- and democracy from the notion of pa- ción de parrhesia, tal y como esta fue rrhesia, as Foucault treated it during his rescatada por Michel Foucault durante last works. The Foucauldian approach sus últimos trabajos. La propuesta fou- establishes a stressing linkage on one caultiana predica una vinculación cons- another: there can be no democracy wi- titutiva, no exenta de tensiones, entre thout appealing to certain idea of truth, ambas: no puede haber democracia sin but the emergence of such truth invol- referencia a una cierta idea de verdad, ves the existence of a democratic space. pero la emergencia de tal verdad presu- Such space is constructed through the pone la existencia de un espacio demo- critic of every attempt to monopolize crático. La construcción de ese espacio the capacity of saying the truth. In this se realiza sobre la crítica a todo intento sense, the concept of epistemic injusti- de monopolizar la capacidad de decir la ce helps us to understand how political verdad. En este sentido, el concepto de and epistemic dimensions are interwo- injusticia epistémica nos ayuda a enten- ven in the democratic process. -

Rachel Elizabeth Zuckert Department of Philosophy 5728 N. Kenmore

Rachel Elizabeth Zuckert Department of Philosophy 5728 N. Kenmore Ave, 3N Northwestern University Chicago, IL 60660 Kresge 3-512 1880 Campus Drive home: (773) 728-7927 Evanston, IL 60208 work: (847) 491-2556 [email protected] Education: 2000 PhD, University of Chicago, Department of Philosophy and the Committee on Social Thought 1995 MA, University of Chicago, Committee on Social Thought 1992 B.A. (1), Oxford University (Philosophy and Modern Languages) 1990 B.A. (Summa Cum Laude; Highest Honors in Philosophy; Phi Beta Kappa), Williams College Areas of Specialization: Kant and eighteenth-century philosophy Aesthetics Areas of Competence: Early modern philosophy Nineteenth-century philosophy Feminist philosophy Languages: French German Academic Employment: 2018- Professor of Philosophy, Northwestern University; affiliated with the German Department 2008-18 Associate Professor of Philosophy, Northwestern University; affiliated with the German Department 2011-18 2006-2008 Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Northwestern University 2001-2006 Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Rice University 1999-2001 Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Bucknell University Zuckert 2 Publications: Books Kant on Beauty and Biology: An Interpretation of the Critique of Judgment, Cambridge University Press, 2007. Awarded the American Society for Aesthetics Monograph Prize (2008); reviewed in British Journal for the History of Philosophy, Comparative and Continental Philosophy, Graduate Faculty Philosophy Journal, Journal of the History of Philosophy, Metascience, Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, Review of Metaphysics, and subject of review essays in Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism and Kant Yearbook Herder’s Naturalist Aesthetics, Cambridge University Press, forthcoming (2019). Edited Volume Hegel on Philosophy in History, co-edited with James Kreines, Cambridge University Press, 2017. -

Parrhesia 30 · 2019 Parrhesia 30 · 2019 · 1-17

parrhesia 30 · 2019 parrhesia 30 · 2019 · 1-17 critical approaches to continental philosophy: intellectual community, disciplinary identity, and the politics of inclusion timothy laurie, hannah stark and briohny walker This article examines what it means to produce critical continental philosophy in contexts where the label of “continental” may seem increasingly tenuous, if not entirely anachronistic. We follow Ghassan Hage in understanding “critical thought” as enabling us “to reflexively move outside of ourselves such that we can start seeing ourselves in ways we could not have possibly seen ourselves, our culture or our society before.”1 Such thought may involve an interrogation of our own conditions of knowledge production, by giving us “access to forces that are outside of us but that are acting on us causally.”2 Our argument in this article is that critical approaches within continental philosophy need to examine a multi- plicity of ways that disciplines can be defined and delimited, and to understand the ways that gender, geography, and coloniality (among other forces) shape the intellectual and social worlds of continental philosophy. In doing so, we want to consider the ways that familiar debates around intellectual and institutional biases might be enhanced by a closer consideration of process-based aspects of disciplinary self-reproduction, and we take as our example the Australasian Soci- ety for Continental Philosophy (ASCP) conference at the University of Tasmania (November 29-December 1, 2017).3 We also consider Nelson Maldonado-Torres’ notion of “post-continental philosophy,” and reflect on the implications of such a venture in the Australian context. But to begin with, we want to navigate a path between two modes of criticism commonly directed toward philosophy as a dis- cipline. -

Published Version: John Lippitt, ‘Forgiveness: a Work of Love?’, Parrhesia: a Journal of Critical Philosophy, Issue 28: 19-39, November 2017

Research Archive Citation for published version: John Lippitt, ‘Forgiveness: A Work of Love?’, Parrhesia: A Journal of Critical Philosophy, Issue 28: 19-39, November 2017. Link to published version: https://www.parrhesiajournal.org/ Document Version: This is the Published Version. Copyright and Reuse: © 2017 The Author. This is an Open Access article made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 3.0 Unported license (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/, which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way. Enquiries If you believe this document infringes copyright, please contact the Research & Scholarly Communications Team at [email protected] parrhesia 28 · 2017 · 19-39 forgiveness: a work of love? john lippitt1 What difference would it make to our understanding of the process of interpersonal forgiveness to approach it as what Kierkegaard calls a “work of love”? In this article, I argue that such an approach—which I label “love’s forgiveness”—challenges key assumptions in two prominent philosophical accounts of forgiveness. First, it challenges “desert-based” views, according to which forgiveness is conditional upon such features as the wrongdoer’s repentance and making amends. But second, it also avoids legitimate worries raised against some forms of unconditional forgiveness. I argue that what we may call “love’s vision” has a crucial role to play in interpersonal forgiveness. Against the objection that viewing forgiveness as a work of love is problematic because love involves a certain wilful blindness, I argue (drawing on both Kierkegaard and Troy Jollimore) that a) love has its own epistemic standards, and b) pace Jollimore’s remarks on agape, his claims about romantic love and friendship can in the relevant respects be extended to the case of agapic neighbour-love. -

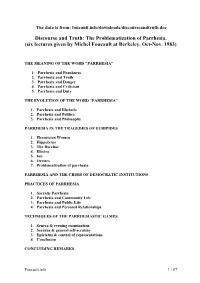

Discourse and Truth: the Problematization of Parrhesia. (Six Lectures Given by Michel Foucault at Berkeley, Oct-Nov

The data is from: foucault.info/downloads/discourseandtruth.doc Discourse and Truth: The Problematization of Parrhesia. (six lectures given by Michel Foucault at Berkeley, Oct-Nov. 1983) THE MEANING OF THE WORD "PARRHESIA" 1. Parrhesia and Frankness 2. Parrhesia and Truth 3. Parrhesia and Danger 4. Parrhesia and Criticism 5. Parrhesia and Duty THE EVOLUTION OF THE WORD “PARRHESIA” 1. Parrhesia and Rhetoric 2. Parrhesia and Politics 3. Parrhesia and Philosophy PARRHESIA IN THE TRAGEDIES OF EURIPIDES 1. Phoenician Women 2. Hippolytus 3. The Bacchae 4. Electra 5. Ion 6. Orestes 7. Problematization of parrhesia PARRHESIA AND THE CRISIS OF DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTIONS PRACTICES OF PARRHESIA 1. Socratic Parrhesia 2. Parrhesia and Community Life 3. Parrhesia and Public Life 4. Parrhesia and Personal Relationships TECHNIQUES OF THE PARRHESIASTIC GAMES 1. Seneca & evening examination 2. Serenus & general self-scrutiny 3. Epictetus & control of representations 4. Conclusion CONCLUDING REMARKS Foucault.info 1 / 67 The Meaning of the Word " Parrhesia " The word "parrhesia" [παρρησία] appears for the first time in Greek literature in Euripides [c.484-407 BC], and occurs throughout the ancient Greek world of letters from the end of the Fifth Century BC. But it can also still be found in the patristic texts written at the end of the Fourth and during the Fifth Century AD -dozens of times, for instance, in Jean Chrisostome [AD 345-407] . There are three forms of the word : the nominal form " parrhesia " ; the verb form "parrhesiazomai" [παρρησιάζοµαι]; and there is also the word "parrhesiastes"[παρρησιαστής] --which is not very frequent and cannot be found in the Classical texts. -

Implications of Foucault's Parrhesia

EJBO Electronic Journal of Business Ethics and Organization Studies Vol. 17, No. 2 (2012) Can we organize courage? Implications of Foucault’s parrhesia Wim Vandekerckhove 1. Introduction order to manage the cattle. A shepherd Suzan Langenberg without self-criticism is not able to take As the financial crisis unfolded, it be- care of his cattle. The strength of the cat- came clear that many people inside the tle depends on the shepherd’s attention Abstract financial sector were aware of the risks for the smallest detail. Ethics in organizations, raising they were taking. We also heard of the In this paper we approach the issue of concerns, and whistleblowing rare individual who tried to raise his con- ‘standing up’ and raising concerns from have been previously theorized cerns with the SEC about Madoff. But Foucault’s third period – his writings on it was amazing how many people wilfully parrhesia, a concept of critique from an- through Foucault’s work on the played along, and how the few individu- cient Greece which denotes the courage power/knowledge bond. However, als who raised concerns were blocked or of speaking frankly and where the truth approaching these issues through overlooked. lies not necessarily in what is being said, the work from Foucault’s third Obviously, this is not the only cause of but rather in the fact that someone is period on parrhesia, or fearless the crisis. Moreover, it is not an exclusive taking the courage to speak and express speech remains an underdeveloped characteristic of the latest crisis. But the critique. organizational dynamic which appears to Whilst some authors argue that route. -

Political Rhetoric: the Modern Parrhesia

The Catalyst Volume 4 | Issue 1 Article 5 2017 Political Rhetoric: The oM dern Parrhesia Jessica Townsend University of Southern Mississippi, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://aquila.usm.edu/southernmisscatalyst Part of the Political Theory Commons Recommended Citation Townsend, Jessica (2017) "Political Rhetoric: The odeM rn Parrhesia," The Catalyst: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. DOI: 10.18785/cat.0401.05 Available at: http://aquila.usm.edu/southernmisscatalyst/vol4/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC talyst by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Catalyst Volume 4 | Issue 1 | Article 5 2017 Political Rhetoric: The Modern Parrhesia Jessica Townsend The French philosopher Michel Foucault is substantial manner by speaking this truth, use best known among academics as a theorizer this truth to criticize the audience, and feel a of human nature and social relationships. sense of duty to speak this criticism (Foucault Although his areas of expertise did not 1983). The risk that goes along with parrhesia encompass politics, which he attempted typically includes risk of life, punishment, or to avoid altogether in his writings, many significant loss of social standing. Because of of his philosophical ideas have been re- this, the truth-teller must be subordinate to examined inside a political context. One of the audience. However, the one speaking with his major theories, the idea of free speech parrhesia, the parrhesiastes, also must be free known as parrhesia, has made its way to the to speak the truth freely of his own accord; foreground of scrutiny by political theorists meaning that he must also not be a slave or as well as an internationally-acclaimed non-citizen, in the case of ancient Greece expert in rhetoric and professor by the name (Foucault 1983).