Rapid Assessment of Forest Protection Activities Mongolia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biosecurity Risk Assessment

An Invasive Risk Assessment Framework for New Animal and Plant-based Production Industries RIRDC Publication No. 11/141 RIRDCInnovation for rural Australia An Invasive Risk Assessment Framework for New Animal and Plant-based Production Industries by Dr Robert C Keogh February 2012 RIRDC Publication No. 11/141 RIRDC Project No. PRJ-007347 © 2012 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-74254-320-8 ISSN 1440-6845 An Invasive Risk Assessment Framework for New Animal and Plant-based Production Industries Publication No. 11/141 Project No. PRJ-007347 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. -

Risk Analysis of Mongolian Erannis Jacobsoni Djak's Invasion Into The

Risk Analysis of Mongolian Erannis Jacobsoni Djak’s Invasion into the Inner Mongolia Area Xiaojun Huang 1,2,3,4, Yuhai Bao 2, Altanchimeg D5, Buren4, Fumiao1,Yongmei1 1 College of Geographical Science,Inner Mongolia Normal University,Huhhot 010022,China 2 Key Laboratory of Remote Sensing & Geography Information System ,Inner Mongolia Normal University,Huhhot 010022,China 3 College of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou730000,China 4 Institute of Natural disaster prevention and Control,Inner Mongolia Normal University,Huhhot 010022,China 5 Institute of Biology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences,Ulan Bator, Mongolia 蒙古国雅氏落叶松尺蠖入侵内蒙古地区的风险分析 黄晓君 1,2,3,4,包玉海 2,Altanchimeg D 5,布仁 4,付苗 1,咏梅 1 1 内蒙古师范大学地理科学学院,内蒙古 呼和浩特 010022 2 内蒙古自治区遥感与地理信息系统重点实验室,内蒙古 呼和浩特 010022 3 兰州大学资源环境学院,甘肃 兰州 730000 4 内蒙古师范大学自然灾害防治研究所,内蒙古 呼和浩特 010022 5 蒙古国科学院生物研究所,乌兰巴托 蒙古国 Abstract area of extremely high and high suitable risk areas in the Aershan city are 40380.21 hectares and 251409.34 Erannis jacobsoni Djak is the most important forest pest hectares respectively. The environmental variables that in Mongolia and has seriously destructive effect to forest have important effects on invasion risk of Erannis ecological system. It is important to study the invasion jacobsoni Djak included forest,mean temperature of risk of Inner Mongolia, which is of great significance for warmest quarter,annual precipitation, max temperature of the effective prevention of cross-border disaster. Based warmest month and min temperature of coldest month. on it, firstly, this study discussed the risk of Mongolia Erannis jacobsoni Djak spreading into Inner Mongolia; Keywords: Erannis jacobsoni Djak; Invasion risk; Then using the field survey point data of Mongolia maximum entropy(Maxent) niche model; Erannis jacobsoni Djak and environmental variables data environmental variables such as biological climatic factors, altitude, forest, predicted the potential suitable risk areas distribution of 摘要 this pest in Inner Mongolia by means of maximum entropy(Maxent) niche model and GIS technology. -

© Амурский Зоологический Журнал II(4), 2010. 303-321 © Amurian

© Амурский зоологический журнал II(4), 2010. 303-321 УДК 595.785 © Amurian zoological journal II(4), 2010. 303-321 ПЯДЕНИЦЫ (INSECTA, LEPIDOPTERA: GEOMETRIDAE) БОЛЬШЕХЕХЦИРСКОГО ЗАПОВЕДНИ- КА (ОКРЕСТНОСТИ ХАБАРОВСКА) Е.А. Беляев1, С.В. Василенко2, В.В. Дубатолов2, А.М. Долгих3 [Belyaev E.A., Vasilenko S.V., Dubatolov V.V., Dolgikh A.M. Geometer moths (Insecta, Lepidoptera: Geometridae) of the Bolshekhekhtsirskii Nature Reserve (Khabarovsk suburbs)] 1Биолого-почвенный институт ДВО РАН, пр. Сто лет Владивостоку, 159, Владивосток, 690022, Россия. E-mail: beljaev@ibss. dvo.ru 1Institute of Biology and Soil Science, Far Eastern Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, Prospect 100 Let Vladivostoku, 159, Vladivostok, 690022, Russia. E-mail: [email protected]. 2Сибирский зоологический музей, Институт систематики и экологии животных СО РАН, ул. Фрунзе 11, Новосибирск, 630091, Россия. E-mail: [email protected]. 2Siberian Zoological Museum, Institute of Systematics and Ecology of Animals, Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, Frunze str. 11, Novosibirsk, 630091, Russia. E-mail: [email protected]. 3Большехехцирский заповедник, ул. Юбилейная 8, пос. Бычиха, Хабаровский район, Хабаровский край, 680502, Россия. E-mail: [email protected]. 3Nature Reserve Bolshekhekhtsyrskii, Yubileinaya street 8, Bychikha, Khabarovsk District, Khabarovskii Krai, 680502, Russia. E-mail: [email protected]. Ключевые слова: Пяденицы,Geometridae, Большехехцирский заповедник, Хехцир, Хабаровск Key words: Geometer moths,Geometridae, Khekhtsyr, Khabarovsk, Russian Far East Резюме. Приводится 328 видов семейства Geometridae, собранных в Большехехцирском заповеднике. Среди них 34 вида впер- вые указаны для территории Хабаровского края. Summary. 328 Geometridae species were collected in the Bolshekhekhtsirskii Nature Reserve, 34 of them are recorded from Khabarovskii Krai for the first time. Большехехцирский заповедник, организованный в вершинным склонам среднегорья. -

Far Eastern Entomologist Number 386: 8-20 ISSN 1026-051X July 2019

Far Eastern Entomologist Number 386: 8-20 ISSN 1026-051X July 2019 https://doi.org/10.25221/fee.386.2 http://zoobank.org/References/33D1308D-3DCC-4460-A419-53ED20C9F35C NEW DATA ON LEPIDOPTERA OF WEST SIBERIAN PLAIN, RUSSIA S. A. Knyazev1), V. V. Ivonin2), P. Ya. Ustjuzhanin3), S. V. Vasilenko4), V. V. Rogalyov5) 1) Russian Entomological Society, Irtyshskaya naberezhnaya str., 14-16, Omsk, 644042, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] 1) Altai State University, Lenina, 61, Barnaul, 656049, Russia. 2) Vystavochnaya str., 32/1-81, Novosibirsk, 630078, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] 3) Altai State University, Lenina, 61, Barnaul, 656049, Russia. 4) Institute of Systematics and Ecology of Animals, SB RAS, Frunze str. 11, 630091, Novosibirsk, Russia E-mail: [email protected] 5) Lukashevitsha str., 11-61, Omsk, 644092, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] Summary. A list of 32 species of Lepidoptera from the south part of West Siberian Plain is given. Twenty-five species are reported from the territory of the Omsk Province for the first time, six species are new to the Novosibirsk Province. Eight species are new to the Russian part of the West Siberian Plain. Bucculatrix cristatella (Zeller, 1839) is reported as new for the Asian part of Russia. Key words: Lepidoptera, fauna, new records, Omsk Province, Novosibirsk Province, Siberia, Asia. С. А. Князев, В. В. Ивонин, П. Я. Устюжанин, С. В. Василенко, В. В. Рогалёв. Новые данные по чешуекрылым насекомым (Lepidoptera) Западно-Сибирской низменности, Россия // Дальневосточный энтомолог. 2019. N 386. С. 8-20. Резюме. Приведен список 32 видов чешуекрылых с юга Западно-Сибирской рав- нины. -

Forestry Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Forestry Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Forest Health & Biosecurity Working Papers OVERVIEW OF FOREST PESTS MONGOLIA January 2007 Forest Resources Development Service Working Paper FBS/26E Forest Management Division FAO, Rome, Italy Forestry Department Overview of forest pests - Mongolia DISCLAIMER The aim of this document is to give an overview of the forest pest1 situation in Mongolia. It is not intended to be a comprehensive review. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. © FAO 2007 1 Pest: Any species, strain or biotype of plant, animal or pathogenic agent injurious to plants or plant products (FAO, 2004). Overview of forest pests - Mongolia TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction..................................................................................................................... 1 Forest pests...................................................................................................................... 1 Naturally regenerating forests..................................................................................... 1 Insects ..................................................................................................................... 1 Diseases.................................................................................................................. -

Tolerance to Insect Defoliation: Biocenotic Aspects

TOLERANCE TO INSECT DEFOLIATION: BIOCENOTIC ASPECTS ANDREY A. PLESHANOV, VICTOR I. VORONIN, ELENA S. KHLIMANKOVA, and VALENTINA I. EPOVA Siberian Institute of Plant Physiology and Biochemistry Siberian Branch of the U.S.S.R. Academy of Sciences Irkutsk 664033 U.S.S.R. INTRODUCTION Woody plant resistance to insect damage is of great importance in forest protection, and tree tolerance is an important element of this resistance. The compensating mechanisms responsible for tolerance are nonspecific as a rule and develop after damage has been caused by phytophagous animals or other unfavorable effects. Beyond that, plant tolerance depends on duration, repetition, and phenological periods of the damage effects, and on environmental conditions. We have studied of radial increment patterns in trees as a measure of their physiological state. This approach may be tested in areas infested by various dendrophagous species and is especially useful if the outbreak areas are vast, similar dynamics prevail in different forest site conditions, and the damage inflicted generally does not cause tree mortality. In these respects, the areas infested by Zeiraphera @seanu Hbn., Dasychira abietis Schiff., Maera anastomosis L., and Leucoma salicis L. represent potentially significant conditions for estimation of the defoliation tolerance of larch, pine, and aspen trees, respectively, in Eastern Siberia. TREE GROWTH RESPONSES TO DEFOLIATION Fig. 1 shows the dynamics of radial increment of Larix sibirica in two biotopes that contrast in heat and water supply. The first curve shows the decrease in the increment caused by Zeiraphera grireana Hbn. defoliation in central larch taiga forests. Tree damage in 1953 and 1971 resulted in increment decline for the next 5 to 7 years. -

Data Sheet on Erannis Jacobsoni

EUROPEAN AND MEDITERRANEAN PLANT PROTECTION ORGANIZATION ЕВРОПЕЙСКАЯ И СРЕДИЗЕМНОМОРСКАЯ ОРГАНИЗАЦИЯ ПО КАРАНТИНУ И ЗАЩИТЕ РАСТЕНИЙ ORGANIZATION EUROPEENNE ET MEDITERRANEENNE POUR LA PROTECTION DES PLANTES Data Sheets on Forest Pests Erannis jacobsoni IDENTITY Name: Erannis jacobsoni Diakonoff Synonyms: Hybernia jacobsoni Taxonomic position: Insecta: Lepidoptera: Geometridae Common name: Geometrid of Yakobson (English); пяденица Якобсона (Russian). Bayer computer code: ERANJA HOSTS E. jacobsoni can damage different species of Larix (mainly Larix gmelinii (= Larix dahurica) and Larix sibirica (= Larix sukaczevii)). GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION EPPO region: Russia (east of Southern Siberia, Transbaïkalia, south of North – Eastern Siberia, Southern Far East). Asia: Russia (east of Southern Siberia, Transbaïkalia, south of North – Eastern Siberia, Southern Far East), Mongolia. EU: Absent Main outbreaks of E. jacobsoni occurs in forests around Baïkal lake (republic of Buryatia, oblast’s of Chita and Irkutsk, northern Mongolia). BIOLOGY Adults of E. jacobsoni in its natural range usually appear in the middle of September and occur till the middle of October with the maximum of activity at the end of September. Females have no wings and do not fly. They have negative geotaxis and move actively on the surface of the soil and up on the trunks of larch trees. They lay eggs under scales of the trunks bark and in cracks of branches bark. Migrative capacities of E. jacobsoni are limited because of non-flying females. At this reason, pest populations develop on the same trees during many consecutive years and may rich the population density till 6000 caterpillars per tree. Eggs overwinter and neonate caterpillars appear at the end of May and in the beginning of June. -

Dendroindication of Retrospective Larch Defoliation

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Biology 2018 11(3): 275-284 ~ ~ ~ УДК 630*634.0.453:582.47:632.212:581.143.5 Dendroindication of Retrospective Larch Defoliation Tatyana I. Morozova and Viktor I. Voronin* Siberian Institute of Plant Physiology and Biochemistry SB RAS 123 Lermontov Str., Irkutsk, 664033, Russia Received 08.07.2016, received in revised form 04.10.2016, accepted 04.04.2018, published online 19.04.2018 We propose a method for dating of growth seasons of Siberian larch (Larix sibirica Ledeb.) following insect infestation events and defoliation. Needle damage during the growth phase triggers tree investment into additional growth of brachyblasts within the same season. Dissecting brachyblasts allows the identification of these secondary growth events. We tested this method in the Baikal region, East Siberia, in larch forest sites infested by the gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar L.) from 1997 to 2000. Defoliation of trees due to the infestation was highest in 1997 (63%) and decreased gradually to 46% in 1998, 50% in 1999 and 35% in 2000. During the period of the Lymantria dispar outbreak some brachyblasts had needles reduced by four times after defoliation. The proposed method allows retrospective identification of years of larch canopy damage and defoliation not only by insects, but also fungi or toxic gases in the case of early summer and summer defoliation. Wintering buds are already formed during this period, so defoliation and elimination of its inhibiting impact (power) on the growth of wintering buds results in their fast regeneration. Keywords: Siberian larch, defoliation, radial and brachiblasts increment. Citation: Morozova T.I., Voronin V.I. -

FOLIA ENTOMOLOGICA HUNGARICA ROVARTANI KÖZLEMÉNYEK Volume 78 2017 Pp

FOLIA ENTOMOLOGICA HUNGARICA ROVARTANI KÖZLEMÉNYEK Volume 78 2017 pp. 257–261 Erannis jacobsoni Djakonov, 1926: new for the fauna of Korea (Lepidoptera, Geometridae: Ennominae) Balázs Tóth Hungarian Natural History Museum, Department of Zoology H-1088 Budapest, Baross utca 13, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract – Erannis jacobsoni sichotenaria Kurentzov, 1937 is recorded for the fi rst time from the Korean Peninsula on the basis of one male specimen deposited in the collection of the Hungarian Natural History Museum, Budapest. A key to the males of the Siberian and Pacifi c species of Eran- nis Hübner, 1825 are given. With 8 fi gures. Key words – Erannis, Geometridae, Korean Peninsula, new record, winter moth INTRODUCTION At present, two species of the genus Erannis Hübner, 1825 are known to oc- cur in the Pacifi c coasts of the Palaearctic Region, of which E. golda Djakonov, 1929 has been recorded from the southern part of the Korean Peninsula for a long time (Shin 1996). When the Korean Ennominae material deposited in the Hungarian Natural History Museum (HNHM) was catalogued, it was recorded as new for North Korea by Bálint & Katona (2011). Th e other species, E. jacobsoni is known from Japan, NE China and the Russian Far East up to now, but there is no published record from Korea. While studying the Korean Ennominae collection of the HNHM, I found one male specimen assigned to E. golda, which was diff erent from the other specimens, rather similar to E. defoliaria (Clerck, 1759) based on its wing traits (Fig. 1). Th e aim of the present paper is to document this specimen and clarify its identity. -

Volume 2, Chapter 12-15: Terrestrial Insects: Holometabola

Glime, J. M. 2017. Terrestrial Insects: Holometabola – Lepidoptera: Geometroidea – Noctuoidea. Chapt. 12-15. In: Glime, J. M. 12-15-1 Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 2. Bryological Interaction. Ebook sponsored by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 19 July 2020 and available at <http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology2/>. CHAPTER 12-15 TERRESTRIAL INSECTS: HOLOMETABOLA – LEPIDOPTERA: GEOMETROIDEA – NOCTUOIDEA TABLE OF CONTENTS GEOMETROIDEA ........................................................................................................................................ 12-15-2 Geometridae – Geometrid Moths (Inch Worms) .................................................................................... 12-15-2 LASIOCAMPOIDEA .................................................................................................................................. 12-15-12 Lasiocampidae – Snout Moths .............................................................................................................. 12-15-12 NOCTUOIDEA............................................................................................................................................ 12-15-12 Arctiidae – Tiger Moths, etc. ................................................................................................................ 12-15-12 Erebidae ................................................................................................................................................ 12-15-13 -

Lepidoptera: Geometridae) of the Baikal Region, Russia

Number 391: 1-23 ISSN 1026-051X September 2019 https://doi.org/10.25221/fee.391.1 http://zoobank.org/References/09FA2576-7AA8-42EA-ADFD-D1CD7C5C6600 NEW DATA ON GEOMETRID MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA: GEOMETRIDAE) OF THE BAIKAL REGION, RUSSIA I. A. Makhov 1, 2), E. A. Beljaev 3*) 1) Saint Petersburg State University, Biological Faculty, St. Petersburg 199034, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] 2) Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg 199034, Russia. 3) Federal Scientific Center of the East Asia Terrestrial Biodiversity, Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Vladivostok 690022, Russia. *Corresponding author, E-mail: [email protected] Summary. The list of 52 species of geometrid moths (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) of the Baikal region (Irkutskaya oblast and Buryatia, Russia) is given. Rheumaptera neocervinalis Inoue, 1982 is reported as new for Siberia, 3 species are new for Baikal region, 18 species are new for Irkutskaya oblast and 4 species are new for Buryatia; distribution in the Baikal region of 4 species is confirmed; literature reference of 23 species from the region are considered as dubious. As result, total number of geo- metrids in the Baikal region reaches to 347 species from 153 genera. Genus name Scardostrenia Sterneck, 1928, stat. n., is removed from synonymy with the name Proteostrenia Warren, 1895; original combination of the name Scardostrenia reticu- lata Sterneck, 1928, comb. resurr. is restored. A key to Ourapteryx ussurica Inoue, 1993 and Ourapteryx sambucaria (Linnaeus, 1758) is given. Accuracy of the original geographic labels of the holotypes of Proteostrenia reticulata transbaicalensis Wehrli, 1939, Erannis bajaria var. -

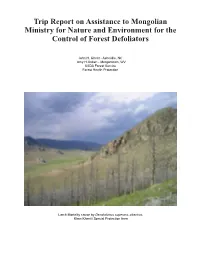

Trip Report on Assistance to Mongolian Ministry for Nature and Environment for the Control of Forest Defoliators

Trip Report on Assistance to Mongolian Ministry for Nature and Environment for the Control of Forest Defoliators John H. Ghent - Asheville, NC Amy H.Onken - Morgantown, WV USDA Forest Service Forest Health Protection Larch Mortality cause by Dendrolimus superans sibericus Khan Khentii Special Protection Area Assistance to Mongolian Ministry of Nature and Environment for the Control of Forest Defoliators John H. Ghent - Asheville, NC Amy H. Onken - Morgantown, WV Abstract In the fall of 2003, the USDA Forest Service assisted the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations in training and operations for the control of severe outbreaks of forest defoliators in Mongolia. Unsea- sonably cool temperatures delayed insect development and treatment was postponed until 2004. The Forest Service Forest Health Protection International Activities Team funded a return trip to assist in treatment opera- tions and to gather information on potential invasive pest species. Background Severe insect pest infestations in forests and urban trees are causing increasing concern both in terms of loss of valuable forest resources and also to the changing face of the urban landscape. Since 1980, 101,100 hectares (250,000 acres) of forest have been damaged due to insects and diseases. The volumes of most economically valuable tree species such as pines and larch are decreasing year by year due to insect pests and diseases. The pine forests of Tuj, Range of Arangat (Selenge aimag) and Duurlig (Khentii aimag) (Figure 1) have already been destroyed by insect damage and wildfire. Many of these forest stands have now reverted to birch forests (Betula sp.) Figure 1.