The Plight of Whitebark Pine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White Cloud Milkvetch), a Region 4 Sensitive Species, on the Sawtooth National Forest

FIELD INVESTIGATION OF ASTRAGALUS VEXILLIFLEXUS VAR. NUBILUS (WHITE CLOUD MILKVETCH), A REGION 4 SENSITIVE SPECIES, ON THE SAWTOOTH NATIONAL FOREST by Michael Mancuso and Robert K. Moseley Natural Heritage Section Nongame/Endangered Wildlife Program Bureau of Wildlife December 1990 Idaho Department of Fish and Game 600 South Walnut, P.O. Box 25 Boise, Idaho 83707 Jerry M. Conley, Director Cooperative Challenge Cost-share Project Sawtooth National Forest Idaho Department of Fish and Game Purchase Order No. 40-0261-0-0801 ABSTRACT An inventory for Astragalus vexilliflexus var. nubilus (White Cloud milkvetch) was conducted on the Sawtooth National Forest by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game's Natural Heritage Program during August of 1990. The inventory was a cooperative Challenge Cost-share project between the Department and the Sawtooth National Forest. White Cloud milkvetch is a narrow endemic to the White Cloud Peaks and Boulder Mountains of central Idaho, in Custer County. Populations are scattered along the ridge systems that slope generally west to east on the east side of the White Cloud crest. Additionally, one population from the Bowery Creek drainage of the Boulder Mountains is known. It is a high elevation species, found mostly on exposed, dry, rocky ridge crests or upper slopes that typically support a relatively sparse vegetation cover. Prior to our 1990 survey, the species was known from three populations. Five new populations were discovered during the 1990 field investigation. Together, these eight populations support approximately 5,700 plants and cover an area less than 40 acres. Both current and potential threats have been identified at several populations. -

Idaho Mountain Goat Management Plan (2019-2024)

Idaho Mountain Goat Management Plan 2019-2024 Prepared by IDAHO DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME June 2019 Recommended Citation: Idaho Mountain Goat Management Plan 2019-2024. Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Boise, USA. Team Members: Paul Atwood – Regional Wildlife Biologist Nathan Borg – Regional Wildlife Biologist Clay Hickey – Regional Wildlife Manager Michelle Kemner – Regional Wildlife Biologist Hollie Miyasaki– Wildlife Staff Biologist Morgan Pfander – Regional Wildlife Biologist Jake Powell – Regional Wildlife Biologist Bret Stansberry – Regional Wildlife Biologist Leona Svancara – GIS Analyst Laura Wolf – Team Leader & Regional Wildlife Biologist Contributors: Frances Cassirer – Wildlife Research Biologist Mark Drew – Wildlife Veterinarian Jon Rachael – Wildlife Game Manager Additional copies: Additional copies can be downloaded from the Idaho Department of Fish and Game website at fishandgame.idaho.gov Front Cover Photo: ©Hollie Miyasaki, IDFG Back Cover Photo: ©Laura Wolf, IDFG Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG) adheres to all applicable state and federal laws and regulations related to discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, gender, disability or veteran’s status. If you feel you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility of IDFG, or if you desire further information, please write to: Idaho Department of Fish and Game, P.O. Box 25, Boise, ID 83707 or U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Federal Assistance, Mailstop: MBSP-4020, 4401 N. Fairfax Drive, Arlington, VA 22203, Telephone: (703) 358-2156. This publication will be made available in alternative formats upon request. Please contact IDFG for assistance. Costs associated with this publication are available from IDFG in accordance with Section 60-202, Idaho Code. -

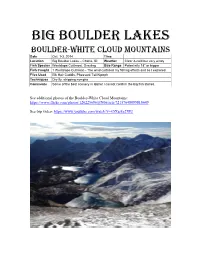

Big Boulder Lakes Boulder-White Cloud Mountains Date Oct

Big Boulder lakes Boulder-White Cloud Mountains Date Oct. 1-3, 2014 Time Location Big Boulder Lakes – Challis, ID Weather Clear & cold but very windy Fish Species Westslope Cutthroat, Grayling Size Range Potentially 18” or bigger Fish Caught 1 Westslope Cuthroat – The wind curtailed my fishing efforts and so I explored Flies Used Elk Hair Caddis, Pheasant Tail Nymph Techniques Dry fly, stripping nymphs Comments Some of the best scenery in Idaho! I cannot confirm the big fish stories. See additional photos of the Boulder-White Cloud Mountains: https://www.flickr.com/photos/120225686@N06/sets/72157648089810649 See trip video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x5Xsska2XlU When I think of big fish in alpine lakes in Idaho – I think of the Big Boulder Lakes. I’ve seen photos and heard several reports that the fishing is excellent for big Cutthroat. Unfortunately, the relentless wind made the wind chill unbearable and I was relegated to bundling up and bagging a couple of peaks instead. But trust me – I have no regrets! The scenery is spectacular and possibly my favorite in Idaho. The Boulder-White Cloud Mountains are part of the Sawtooth National Recreation Area. The fight has continued for decades to designate the Boulder-White Clouds a Wilderness Area. I personally think it rivals the Sawtooths as my favorite backpacking destination in Idaho and I’ve set foot in most mountain ranges save a few in the panhandle. A view near the lower section of trail on the way to Walker Lake Itinerary Wednesday – Drive 4 hours from Boise; less than a mile hike to Jimmy Smith Lake; Backpack 6 to 7 miles to Walker Lake (camp). -

Historical Photograph Collection Special Collections and Archives, University of Idaho Library, Moscow, ID 83844- January 25, 2008 Postcard Collection

Historical Photograph Collection Special Collections and Archives, University of Idaho Library, Moscow, ID 83844- January 25, 2008 Postcard Collection Number Description 9-01-1 Sunset, Idaho. - Printer: Inland-American Ptg Co., Spokane. 1915. Photographer: Barnard Studio, Wallace. 3.5x5.5 printed black and white postcard 9-01-10a Street of Culdesac, Idaho. 1907. 3.5x5.5 black and white postcard 9-01-11a Main Street, Plummer, Idaho. n.d. 3.5x5.5 printed black and white postcard 9-01-12a Murray, Idaho. 1885 photo inset. - Pub. by Ross Hall, Studio, Sandpoint. n.d. 3.5x5.5 printed color 9-01-12b Murray, Idaho. 1890. 3.5x5.5 black and white postcard 9-01-12c Old town of Murray, Idaho. 1886 or 1887. 3.5x5.5 black and white postcard 9-01-13 Stanely Store, Stanley, Idaho. 198? Photographer: Coy Poe Photography. 4x6 printed color postcard 9-01-13b Stanley, Idaho, in the Stanley Basin. IC-14. 198? Photographer: Coy Poe Photography. 4x6 printed 9-01-14a Aerial view of Coeur d'Alene, Idaho. n.d. Photographer: Ross Hall. 4x6 printed color postcard 9-01-14b Scenic setting of Coeur d'alene, Idaho. n.d. Photographer: Ross Hall. 4x6 printed color postcard 9-01-15a Mullan, Idaho, along Interstate 90 below Lookout Pass. - Pub. by Ross Hall Scenics, Sandpoint. n.d. Photographer: Will Hawkins. 4x6 printed color postcard 9-01-16a Osburn, Idaho, in the center of Coeur d'Alene mining region. - Pub. by Ross Hall Scenics, Sandpoint. n.d. Photographer: Ross Hall. 4x6 printed color postcard 9-01-17a Priest River, Idaho. -

Sawtooth NF Stock Users Pamphlet

The Stock User’s Guide Sawtooth National Recreation Area “It was a land of vast silent spaces, of lonely rivers, and of plains where the wild game stared at passing horsemen. We felt the beat of hardy life in our veins, and ours was the glory of work and the joy of living.” Theodore Roosevelt Contents 1 Welcome, Weeds and Frontcountry Camping 2 Avoiding Bruises (and Bears) 3 Where should I go? 4 A few Sawtooth facts 5-6 Leave No Trace at a Glance 7-10 Sawtooth Wilderness Backcountry Stock Tie Areas 11-12 Sawtooth Wilderness Regulations 13-14 Boulder-White Clouds Backcountry Stock Tie Areas and Regulations 15 Checklist: What to Take Back Contact Us Cover Welcome! The mountain meadows, alpine lakes and jagged peaks of the Sawtooth National Recreation Area (SNRA) await your visit. The task of keeping this area beautiful and undamaged belongs to all of us. As a stock user, you must take extra pre- cautions to safeguard the land. The introduction of noxious weeds, overgrazing, tree girdling and other impacts can be easily avoided with a bit of skill and preparation. This user’s guide can help you prepare for your trip. For example, did you know you must get a free wilderness permit from a Forest Service office if you are taking stock overnight into the Sawtooth Wilderness? Are you aware that the eastern side of the Wilderness is closed to grazing? So if you go, bring certified weed seed free feed (no loose hay or straw). For more useful tips, please read on, and have a great journey. -

Winter Recreation and Wolverines

WOLVERINE – WINTER RECREATION RESEARCH PROJECT: INVESTIGATING THE INTERACTIONS BETWEEN WOLVERINES AND WINTER RECREATION 2013 PROGRESS REPORT NOVEMBER 16, 2013 KIMBERLY HEINEMEYER ROUND RIVER CONSERVATION STUDIES 284 W 400 N, SUITE 105 SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH 84103 AND JOHN R. SQUIRES RESEARCH WILDLIFE BIOLOGIST ROCKY MOUNTAIN RESEARCH STATION ROOM 263, FEDERAL BUILDING 200 E. BROADWAY MISSOULA, MT 59802 Wolverine – Winter Recreation Study, 2013 Progress Report WOLVERINE – WINTER RECREATION RESEARCH PROJECT: Investigating the Interactions between Wolverines and Winter Recreation 2013 PROGRESS REPORT November 16, 2013 PREPARED BY: KIMBERLY HEINEMEYER ROUND RIVER CONSERVATION STUDIES 284 WEST 400 NORTH, SUITE 105 SALT LAKE CITY, UT 84103 [email protected] AND JOHN R. SQUIRES RESEARCH WILDLIFE BIOLOGIST ROCKY MOUNTAIN RESEARCH STATION ROOM 263, FEDERAL BUILDING 200 E. BROADWAY MISSOULA, MT 59802 [email protected] WITH THE SUPPORT OF PROJECT PARTNERS AND COLLABORATORS INCLUDING: Payette National Forest Boise National Forest Sawtooth National Forest Idaho Department of Fish and Game University of Montana Brundage Mountain Resort Central Idaho Recreation Coalition Idaho State Snowmobile Association The Sawtooth Society The Wolverine Foundation US Fish and Wildlife Service And the winter recreation community of Idaho To receive a copy of this report or other project information, see www.forestcarnivores.org Page ii Wolverine – Winter Recreation Study, 2013 Progress Report ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are grateful to our multiple partners and collaborators who have assisted the project in numerous ways. Funding and equipment for the project has been contributed by the US Forest Service, Southwest Idaho Resource Advisory Committee, Southeast Idaho Resource Advisory Committee, Round River Conservation Studies, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Idaho State Snowmobile Association, The Wolverine Foundation, Sawtooth Society, Central Idaho Recreation Coalition, Brundage Mountain Resort and the Nez Perce Tribe. -

Supporting Information Article Title: Increasing Phylogenetic

Supporting Information Article title: Increasing phylogenetic stochasticity at high elevations on summits across a remote North American wilderness Authors: Hannah E. Marx, Melissa Richards, Grahm M. Johnson, and David C. Tank Article acceptance date: The following Supporting Information is available for this article: Appendix S1: Table with target-specific primer pair sequences and citations. Appendix S2: Voucher numbers and collection information for each accession. Appendix S3: Accession number for the high-throughput (miseq) or GenBank (ncbi) se- quence used for each gene region and community matrix. Appendix S4: Table summarizing high-throughput sequencing read statistics and aligned sequence length for each gene region. Appendix S5: Maximum likelihood phylograms estimated from concatenated gene regions of each dataset (total combined, GenBank, and high-throughput). Appendix S6: Comparison of phylogenetic community structure between microhabitats within each summit. Appendix S7: Table summarizing phylogenetic α-diversity. Appendix S8: Table summarizing phylogenetic β-diversity. Appendix S9: Comparison of the datasets used to infer phylogenetic relationships among alpine plant species. 1 Table Appendix 1: Table with target-specific primer pair sequences and citations for each gene region (and segments). Primer 5' Primer 5' Sequence 5' Reference 3' Primer 3' Sequence 3' Reference Pair Name White et al. (1990); White et al. (1990); ITS ITS-5 ggAAggAgAAgTCgTAACAAgg ITS-4 TCCTCCgCTTATTgATATgC Baldwin (1992) Baldwin (1992) atpB1 S1494R TCAgTACACAAAgATTTAAggTCAT -

Hemingway-Boulders and Cecil D. Andrus-White Clouds Wilderness

NATIONAL SYSTEM OF PUBLIC LANDS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT United States Department of Agriculture United States Department of the Interior Forest Service Bureau of Land Management Hemingway-Boulders and Cecil D. Andrus-White Clouds Wilderness Management Plan Sawtooth National Forest, Sawtooth National Recreation Area BLM, Idaho Falls District, Challis Field Office May 7, 2018 For More Information Contact: Kit Mullen, Forest Supervisor Sawtooth National Forest 2647 Kimberly Road East Twin Falls, ID 83301-7976 Phone: 208-737-3200 Fax: 208-737-3236 Mary D’Aversa, District Manager Idaho Falls District 1405 Hollipark Drive Idaho Falls, ID 83401 Phone: 208-524-7500 Fax: 208-737-3236 Description: Castle Peak in the Cecil D. Andrus-White Clouds Wilderness In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. -

The Upper Salmon River Boating Guide, East-Central Idaho

THE UPPER SALMON RIVER BOATING GUIDE, EAST-CENTRAL IDAHO Idaho Department of Fish and Game | U.S. Forest Service | Bureau of Land Management INDEX AND LOCATION MAP NORTH FORK ! r ve S15 Ri on Salm S14 CARMEN ! SALMON TO NEWLAND RANCH —22.9 miles SALMON ! S13 S12 McKIM CREEK TO SALMON —33.4 miles S11 S10 ELLIS ! THOMPSON CREEK TO McKIM CREEK S9 —66.3 miles S8 CHALLIS ! S7 STANLEY TO THOMPSON CREEK —26.4 miles S6 S5 S3 ! S2 S4 ! CLAYTON STANLEY S1 Map Location IDAHO Cover photography © Chad Case UPPER SALMON RIVER BOATING GUIDE, EAST-CENTRAL IDAHO Idaho Department of Fish and Game Salmon Regional Office 99 Highway 93 North Salmon, Idaho 83467 208-756-2271 Sawtooth National Forest 370 American Avenue Jerome, Idaho 83338 208-423-7500 Bureau of Land Management Idaho Falls District 1405 Hollipark Drive Idaho Falls, Idaho 83401 208-524-7500 Bureau of Land Management Challis Field Office 721 East Main Avenue, Suite 8 Challis, Idaho 83226 208-879-6200 Bureau of Land Management Salmon Field Office Salmon-Challis National Forest 1206 S. Challis Street Salmon, Idaho 83467 208-756-5400 THE RIVER’S NAMESAKE The Salmon river supports three separate species of anadromous fish (fish born in fresh water that migrates to the ocean to mature, then returns to fresh water to spawn). A salmon’s life begins and ends here in the moun- tains of Idaho. Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) and sockeye salmon (Onrcorhynchus nerka) travel nearly 900 miles to reach the spawn- ing areas in the Stanley Basin and, unlike steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss), die after spawning. -

Hiking the Sawtooth Mountains of Idaho - 1 July 17, 2021 – July 28, 2021 (Trip# 2153)

Hiking the Sawtooth Mountains of Idaho - 1 July 17, 2021 – July 28, 2021 (trip# 2153) Alice Lake, Sawtooth Wilderness We are glad that you are interested in this exciting trip! Please read the information carefully, and contact us if you have specific questions about this trip: Bill Wheeler 860-324-7374; [email protected] or George Schott 203-223-1677; [email protected]. For general questions about AMC Adventure Travel, please email [email protected]. SUMMARY The Sawtooth Range is a mountain range of the Rocky Mountains, located in Central Idaho. It is named for its jagged peaks. Much of the range is located within the Sawtooth Wilderness. Bordered to the east lies 30-mile long Sawtooth Valley and the town of Stanley, our home for the majority of this trip. To the east of the valley are the White Cloud Mountains. These peaks offer a unique perspective, looking across the valley at the jagged Sawtooth. On this 12-day adventure, we'll explore the alpine lakes, high divides and summits of the Sawtooth and White Cloud. After arriving in Boise, Idaho, we’ll meet the group at our welcome dinner and gather some supplies for the trip. After one night in Boise, we’ll leave it behind for a three hour scenic drive to the town of Stanley, our home for eight nights. We'll enjoy moderate to challenging hikes ranging from 7 to 17 miles per day. We’ll see wildflowers and wildlife, pristine lakes, jagged peaks and one panorama after another. We’ll experience the unique terrain and mountain air as we climb to several divides and summits between 9,000’ and 10,000’. -

Lassen National Forest Over-Snow Vehicle Use Designation DEIS Mar 15, 2016

March 15, 2016 Chris O’Brien On behalf of Russell Hays, Forest Supervisor Lassen National Forest 2550 Riverside Drive Susanville, CA 96130 [email protected] By Electronic Mail Re: Comments on Lassen OSV Use Designation DEIS Dear Supervisor Hays, Thank you for the opportunity to comment on the Lassen National Forest’s Over-Snow Vehicle (OSV) Use Designation Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS). The Lassen National Forest is the very first forest in the country to undergo winter travel management planning under the Forest Service’s new regulation governing OSV use, subpart C of the Forest Service travel management regulations.1 The rule 1 36 C.F.R. part 212, subpart C. 1 requires national forests with adequate snowfall to designate and display on an “OSV Use Map” specific areas and routes where OSV use is permitted based on protection of resources and other recreational uses. OSV use outside the designated system is prohibited. We are pleased to see that many sections of the DEIS provide a relatively thorough discussion of the impacts associated with OSV use. Unfortunately, the Forest Service has failed to apply that information and analysis to formulate a proposed action and alternatives that satisfy the requirements of the new subpart C regulations. To ensure that rule implementation is off to the right start and avoid the specter of litigation that has plagued summertime travel management planning, it is critical that the Lassen’s OSV use designation planning process: Satisfy the Forest Service’s substantive legal duty to locate each area and trail to minimize resource damage and conflicts with other recreational uses – not just identify or consider those impacts. -

User's Guide to Fish Habitat: Descriptions That Represent Natural

United States Department User’s Guide to Fish Habitat: of Agriculture Forest Service Descriptions that Represent Intermountain Research Station Natural Conditions in the General Technical Salmon River Basin, Idaho Report INT-GTR-322 August 1995 C. Kerry Overton John D. McIntyre Robyn Armstrong Shari L. Whitwell Kelly A. Duncan The Authors Shari L. Whitwell is a computer specialist with the Intermountain Research Station’s Enhancing Fish C. Kerry Overton is a technology transfer specialist Habitat Research Work Unit in Boise, ID. She began with the Intermountain Research Station’s Enhancing work with the Forest Service in 1991. Her primary Fish Habitats Research Work Unit in Boise, ID. He job functions are data base management, analysis, received B.S. degrees in conservation and biology and and display of fish habitat data, and computer sup- an M.S. degree in zoology (aquatic ecology) from Idaho port to the technology transfer program. State University. He joined the Forest Service in 1978 Kelly A. Duncan was a biological technician (fisher- and has worked as a fishery biologist at the District, ies) with the Intermountain Research Station’s En- Forest, and Regional levels in the Pacific Southwest hancing Fish Habitats Research Work Unit in Boise, Region, CA. He joined the Intermountain Research ID. She received her B.S. degree in environmental Station in November 1990 working on the develop- science from Willamette University in 1992. She began ment, evaluation, and transfer of technical tools to work with the Forest Service in 1991 and has been in- assist National Forest fishery biologists. volved with aquatic habitat inventories, videography, John D.