Idaho Mountain Goat Management Plan (2019-2024)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White Cloud Milkvetch), a Region 4 Sensitive Species, on the Sawtooth National Forest

FIELD INVESTIGATION OF ASTRAGALUS VEXILLIFLEXUS VAR. NUBILUS (WHITE CLOUD MILKVETCH), A REGION 4 SENSITIVE SPECIES, ON THE SAWTOOTH NATIONAL FOREST by Michael Mancuso and Robert K. Moseley Natural Heritage Section Nongame/Endangered Wildlife Program Bureau of Wildlife December 1990 Idaho Department of Fish and Game 600 South Walnut, P.O. Box 25 Boise, Idaho 83707 Jerry M. Conley, Director Cooperative Challenge Cost-share Project Sawtooth National Forest Idaho Department of Fish and Game Purchase Order No. 40-0261-0-0801 ABSTRACT An inventory for Astragalus vexilliflexus var. nubilus (White Cloud milkvetch) was conducted on the Sawtooth National Forest by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game's Natural Heritage Program during August of 1990. The inventory was a cooperative Challenge Cost-share project between the Department and the Sawtooth National Forest. White Cloud milkvetch is a narrow endemic to the White Cloud Peaks and Boulder Mountains of central Idaho, in Custer County. Populations are scattered along the ridge systems that slope generally west to east on the east side of the White Cloud crest. Additionally, one population from the Bowery Creek drainage of the Boulder Mountains is known. It is a high elevation species, found mostly on exposed, dry, rocky ridge crests or upper slopes that typically support a relatively sparse vegetation cover. Prior to our 1990 survey, the species was known from three populations. Five new populations were discovered during the 1990 field investigation. Together, these eight populations support approximately 5,700 plants and cover an area less than 40 acres. Both current and potential threats have been identified at several populations. -

Educator's Guide

Educator’s Guide the jill and lewis bernard family Hall of north american mammals inside: • Suggestions to Help You come prepared • essential questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for teaching in the exhibition • map of the Exhibition • online resources for the Classroom • Correlations to science framework • glossary amnh.org/namammals Essential QUESTIONS Who are — and who were — the North as tundra, winters are cold, long, and dark, the growing season American Mammals? is extremely short, and precipitation is low. In contrast, the abundant precipitation and year-round warmth of tropical All mammals on Earth share a common ancestor and and subtropical forests provide optimal growing conditions represent many millions of years of evolution. Most of those that support the greatest diversity of species worldwide. in this hall arose as distinct species in the relatively recent Florida and Mexico contain some subtropical forest. In the past. Their ancestors reached North America at different boreal forest that covers a huge expanse of the continent’s times. Some entered from the north along the Bering land northern latitudes, winters are dry and severe, summers moist bridge, which was intermittently exposed by low sea levels and short, and temperatures between the two range widely. during the Pleistocene (2,588,000 to 11,700 years ago). Desert and scrublands are dry and generally warm through- These migrants included relatives of New World cats (e.g. out the year, with temperatures that may exceed 100°F and dip sabertooth, jaguar), certain rodents, musk ox, at least two by 30 degrees at night. kinds of elephants (e.g. -

Research Natural Areas on National Forest System Lands in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Utah, and Western Wyoming: a Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and Educators

USDA United States Department of Agriculture Research Natural Areas on Forest Service National Forest System Lands Rocky Mountain Research Station in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, General Technical Report RMRS-CTR-69 Utah, and Western Wyoming: February 2001 A Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and E'ducators Angela G. Evenden Melinda Moeur J. Stephen Shelly Shannon F. Kimball Charles A. Wellner Abstract Evenden, Angela G.; Moeur, Melinda; Shelly, J. Stephen; Kimball, Shannon F.; Wellner, Charles A. 2001. Research Natural Areas on National Forest System Lands in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Utah, and Western Wyoming: A Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and Educators. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-69. Ogden, UT: U.S. Departmentof Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 84 p. This guidebook is intended to familiarize land resource managers, scientists, educators, and others with Research Natural Areas (RNAs) managed by the USDA Forest Service in the Northern Rocky Mountains and lntermountain West. This guidebook facilitates broader recognitionand use of these valuable natural areas by describing the RNA network, past and current research and monitoring, management, and how to use RNAs. About The Authors Angela G. Evenden is biological inventory and monitoring project leader with the National Park Service -NorthernColorado Plateau Network in Moab, UT. She was formerly the Natural Areas Program Manager for the Rocky Mountain Research Station, Northern Region and lntermountain Region of the USDA Forest Service. Melinda Moeur is Research Forester with the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain ResearchStation in Moscow, ID, and one of four Research Natural Areas Coordinators from the Rocky Mountain Research Station. J. Stephen Shelly is Regional Botanist and Research Natural Areas Coordinator with the USDA Forest Service, Northern Region Headquarters Office in Missoula, MT. -

Survival and Mortality of Translocated Woodland Caribou Author(S): Bradley B

Survival and Mortality of Translocated Woodland Caribou Author(s): Bradley B. Compton, Peter Zager and Gregg Servheen Reviewed work(s): Source: Wildlife Society Bulletin, Vol. 23, No. 3 (Autumn, 1995), pp. 490-496 Published by: Allen Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3782959 . Accessed: 07/11/2012 15:12 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Allen Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Wildlife Society Bulletin. http://www.jstor.org Caribou survival Survival and mortality of translocated woodland caribou Bradley B. Compton, Peter Zager, and Gregg Servheen AbstractWe monitoredsurvival of 60 woodland caribou (Rangifertarandus) translocatedfrom BritishColumbia to the SelkirkMountains of northernIdaho betweenMarch 1987 and February1992. This translocationwas to assistin recoveryof the endangeredSelkirk population. For all translocatedcaribou combined,estimated annual survivalrates rangedfrom 0.65-0.94 and wereconsistent with declining established populations. No differences(P > 0.10) in survivalwere foundbetween male and femalecaribou or be- tweenmountain and northernecotypes. Causes ofdeath included unknown (n = 14), pre- dation(n = 7), other(n = 4), and human-caused(n = 2), withsummer accounting for the greatestproportion (53o/o). Emigrationof 7 mountainecotype animals also was a loss to the population. -

Horned Animals

Horned Animals In This Issue In this issue of Wild Wonders you will discover the differences between horns and antlers, learn about the different animals in Alaska who have horns, compare and contrast their adaptations, and discover how humans use horns to make useful and decorative items. Horns and antlers are available from local ADF&G offices or the ARLIS library for teachers to borrow. Learn more online at: alaska.gov/go/HVNC Contents Horns or Antlers! What’s the Difference? 2 Traditional Uses of Horns 3 Bison and Muskoxen 4-5 Dall’s Sheep and Mountain Goats 6-7 Test Your Knowledge 8 Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Wildlife Conservation, 2018 Issue 8 1 Sometimes people use the terms horns and antlers in the wrong manner. They may say “moose horns” when they mean moose antlers! “What’s the difference?” they may ask. Let’s take a closer look and find out how antlers and horns are different from each other. After you read the information below, try to match the animals with the correct description. Horns Antlers • Made out of bone and covered with a • Made out of bone. keratin layer (the same material as our • Grow and fall off every year. fingernails and hair). • Are grown only by male members of the • Are permanent - they do not fall off every Cervid family (hoofed animals such as year like antlers do. deer), except for female caribou who also • Both male and female members in the grow antlers! Bovid family (cloven-hoofed animals such • Usually branched. -

Tectonic Alteration of a Major Neogene River Drainage of the Basin and Range

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2016 TECTONIC ALTERATION OF A MAJOR NEOGENE RIVER DRAINAGE OF THE BASIN AND RANGE Stuart D. Parker Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Part of the Tectonics and Structure Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Parker, Stuart D., "TECTONIC ALTERATION OF A MAJOR NEOGENE RIVER DRAINAGE OF THE BASIN AND RANGE" (2016). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 10637. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/10637 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TECTONIC ALTERATION OF A MAJOR NEOGENE RIVER DRAINAGE OF THE BASIN AND RANGE By STUART DOUGLAS PARKER Bachelor of Science, University of North Carolina-Asheville, Asheville, North Carolina, 2014 Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geology The University of Montana Missoula, MT May, 2016 Approved by: Scott Whittenburg, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School James W. Sears, Committee Chair Department of Geosciences Rebecca Bendick Department of Geosciences Marc S. Hendrix Department of Geosciences Andrew Ware Department of Physics and Astronomy Parker, Stuart, M. S., May, 2016 Geology Tectonic alteration of a major Neogene river drainage of the Basin and Range Chairperson: James W. -

Cabinet-Yaak and Selkirk Mountains Grizzly Bear Monitoring Update 610/2019

Cabinet-Yaak and Selkirk Mountains Grizzly Bear Monitoring Update 610/2019 Wayne Kasworm, US Fish and Wildlife Service, 385 Fish Hatchery Road, Libby, MT 59923 (406) 293-4161 ext 205 [email protected] Reports: https://www.fws.gov/mountain-prairie/es/grizzlyBear.php Our 2019 field season began in early May with the arrival of our field technicians for work and training. We spent almost a week on training before crews dispersed to the field. We have two bear capture teams and one hair collection team in the Cabinet-Yaak plus one trap team and two hair collection teams in the Selkirk Mountains. Crews began capture and hair collection efforts on May 18. Capture efforts will emphasize recapture of existing collar bears. The manufacturer of our radio collars alerted us to a software glitch that is causing many of our collars to malfunction. This year’s collars have had the software updated to avoid the issue. Selkirk Mountains Research Monitoring We began 2019 with five grizzly bears collared in the Selkirk Mountains (3 females and 2 males). Capture activities have resulted in the recapture and collar change on one of the females (Figure 1). Trail cameras at the capture site indicated she was accompanied by a 2 year-old offspring, but that bear was not captured. Trapping will continue near the international border to attempt recapture of the other two females. Cabinet-Yaak Research Monitoring We began 2019 with six collared grizzly bears in the Cabinet-Yaak (2 females and 4 males). One of the females was observed in May with two new cubs. -

Antelope, Deer, Bighorn Sheep and Mountain Goats: a Guide to the Carpals

J. Ethnobiol. 10(2):169-181 Winter 1990 ANTELOPE, DEER, BIGHORN SHEEP AND MOUNTAIN GOATS: A GUIDE TO THE CARPALS PAMELA J. FORD Mount San Antonio College 1100 North Grand Avenue Walnut, CA 91739 ABSTRACT.-Remains of antelope, deer, mountain goat, and bighorn sheep appear in archaeological sites in the North American west. Carpal bones of these animals are generally recovered in excellent condition but are rarely identified beyond the classification 1/small-sized artiodactyl." This guide, based on the analysis of over thirty modem specimens, is intended as an aid in the identifi cation of these remains for archaeological and biogeographical studies. RESUMEN.-Se han encontrado restos de antilopes, ciervos, cabras de las montanas rocosas, y de carneros cimarrones en sitios arqueol6gicos del oeste de Norte America. Huesos carpianos de estos animales se recuperan, por 10 general, en excelentes condiciones pero raramente son identificados mas alIa de la clasifi cacion "artiodactilos pequeno." Esta glia, basada en un anaIisis de mas de treinta especlmenes modemos, tiene el proposito de servir como ayuda en la identifica cion de estos restos para estudios arqueologicos y biogeogrMicos. RESUME.-On peut trouver des ossements d'antilopes, de cerfs, de chevres de montagne et de mouflons des Rocheuses, dans des sites archeologiques de la . region ouest de I'Amerique du Nord. Les os carpeins de ces animaux, generale ment en excellente condition, sont rarement identifies au dela du classement d' ,I artiodactyles de petite taille." Le but de ce guide base sur 30 specimens recents est d'aider aidentifier ces ossements pour des etudes archeologiques et biogeo graphiques. -

Geologic Map of the Lemhi Pass Quadrangle, Lemhi County, Idaho

IDAHO GEOLOGICAL SURVEY IDAHOGEOLOGY.ORG IGS DIGITAL WEB MAP 183 MONTANA BUREAU OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MBMG.MTECH.EDU MBMG OPEN FILE 701 Tuff, undivided (Eocene)—Mixed unit of tuffs interbedded with, and directly Jahnke Lake member, Apple Creek Formation (Mesoproterozoic)—Feldspathic this Cambrian intrusive event introduced the magnetite and REEs. CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS Tt Yajl below, the mafic lava flow unit (Tlm). Equivalent to rhyolitic tuff beds (Tct) quartzite, minor siltite, and argillite. Poorly exposed and only in the Whole-rock geochemical analysis of the syenite indicates enrichment in Y of Staatz (1972), who noted characteristic recessive weathering and a wide northeast corner of the map. Description based mostly on that of Yqpi on (54-89 ppm), Nb (192-218 ppm), Nd (90-119 ppm), La (131-180 ppm), and GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE LEMHI PASS QUADRANGLE, LEMHI COUNTY, IDAHO, AND Artificial Alluvial Deposits Mass-Movement Glacial Deposits and range of crystal, lithic, and vitric fragment (pumice) proportions. Tuffs lower the Kitty Creek map (Lewis and others, 2009) to the north. Fine- to Ce (234-325 ppm) relative to other intrusive rocks in the region (data from Deposits Deposits Periglacial Deposits in the sequence commonly contain conspicuous biotite phenocrysts. Most medium-grained, moderately well-sorted feldspathic quartzite. Typically Gillerman, 2008). Mineralization ages are complex, but some are clearly or all are probably rhyolitic. A quartzite-bearing tuff interbedded with mafic flat-laminated m to dm beds with little siltite or argillite. Plagioclase content m Paleozoic (Gillerman, 2008; Gillerman and others, 2008, 2010, and 2013) Qaf Qas Qgty Qalc Holocene lava flows north of Trail Creek yielded a U-Pb zircon age of 47.0 ± 0.2 Ma (12-28 percent) is greater than or sub-equal to potassium feldspar (5-16 as summarized below. -

Representativeness Assessment of Research Natural Areas on National Forest System Lands in Idaho

USDA United States Department of Representativeness Assessment of Agriculture Forest Service Research Natural Areas on Rocky Mountain Research Station National Forest System Lands General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-45 in Idaho March 2000 Steven K. Rust Abstract Rust, Steven K. 2000. Representativeness assessment of research natural areas on National Forest System lands in Idaho. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-45. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 129 p. A representativeness assessment of National Forest System (N FS) Research Natural Areas in ldaho summarizes information on the status of the natural area network and priorities for identification of new Research Natural Areas. Natural distribution and abundance of plant associations is compared to the representation of plant associations within natural areas. Natural distribution and abundance is estimated using modeled potential natural vegetation, published classification and inventory data, and Heritage plant community element occur- rence data. Minimum criteria are applied to select only viable, high quality plant association occurrences. In assigning natural area selection priorities, decision rules are applied to encompass consideration of the adequacy and viability of representation. Selected for analysis were 1,024 plant association occurrences within 21 4 natural areas (including 115 NFS Research Natural Areas). Of the 1,566 combinations of association within ecological sections, 28 percent require additional data for further analysis; 8, 40, and 12 percent, respectively, are ranked from high to low conservation priority; 13 percent are fully represented. Patterns in natural area needs vary between ecological section. The result provides an operational prioritization of Research Natural Area needs at landscape and subregional scales. -

Seasonal Status of the American Pipit in Idaho

SEASONAL STATUS OF THE AMERICAN PIPIT IN IDAHO DANIEL M. TAYLOR, 244 N. 12th, Pocatello,Idaho 83201 In Idaho, the AmericanPipit (Antbus rubescens)has been considered primarilya migrant,either locally common but erratic (Larrison et al. 1967) or uncommonin springand commonin fall (Burleigh1972). Severalother writers(Merriam 1891, Merrill 1898, Newhouse1960, Levy 1962) consid- ered it an abundantfall migrantbut gaveno indicationof actualnumbers. The one (Larrisonet al. 1967) or two (Burleigh1972) winterrecords were from Lewiston.Larrison et al. (1967) suspectedthat pipitsmight breed on someof the state'shigh mountains,while Burleigh(1972) knew of only Merriam's(1891) statementthat they breedin the Salmon River Mountains and a report by L. B. McQueenof breedingin the upper Pahsimeroi drainagenear Borah Peak. This scantinessof breedingevidence may be why the mostrecent A.O.U. checklist(1983) statesthat the AmericanPipit breedslocally on mountaintopsin severalRocky Mountain states but does not specificallylist Idaho. In this paper I consolidateand enhancewhat is known aboutAmerican Pipit distributionin Idaho with reference to adjacent areas. I present evidenceof additionalbreeding, concentrations of thousandsof fall mi- grants,and the species'regular but erraticwintering in much of southern Idaho.I analyzeChristmas Bird Countdata for patternsin winterdistribu- tion relatedto differencesin weather,elevation, geography, and annual variability. METHODS I gatheredrecent American Pipit recordsfrom a literaturereview and my own fieldnotes for the last 15 years.All ChristmasBird Counts(CBCs) for Idahosince 1978 were included,as well as somefrom adjacentMontana and Washington.Long-term counts from southernIdaho were examined statisticallyin a mannersimilar to that of Lauranceand Yensen(1985) and Dunning and Brown (1982). Weather data were extracted from U.S. EnvironmentalData Servicemonthly reports from eachweather station in or closeto eachCBC. -

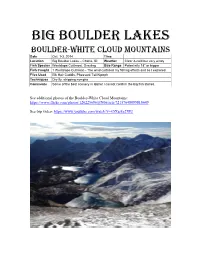

Big Boulder Lakes Boulder-White Cloud Mountains Date Oct

Big Boulder lakes Boulder-White Cloud Mountains Date Oct. 1-3, 2014 Time Location Big Boulder Lakes – Challis, ID Weather Clear & cold but very windy Fish Species Westslope Cutthroat, Grayling Size Range Potentially 18” or bigger Fish Caught 1 Westslope Cuthroat – The wind curtailed my fishing efforts and so I explored Flies Used Elk Hair Caddis, Pheasant Tail Nymph Techniques Dry fly, stripping nymphs Comments Some of the best scenery in Idaho! I cannot confirm the big fish stories. See additional photos of the Boulder-White Cloud Mountains: https://www.flickr.com/photos/120225686@N06/sets/72157648089810649 See trip video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x5Xsska2XlU When I think of big fish in alpine lakes in Idaho – I think of the Big Boulder Lakes. I’ve seen photos and heard several reports that the fishing is excellent for big Cutthroat. Unfortunately, the relentless wind made the wind chill unbearable and I was relegated to bundling up and bagging a couple of peaks instead. But trust me – I have no regrets! The scenery is spectacular and possibly my favorite in Idaho. The Boulder-White Cloud Mountains are part of the Sawtooth National Recreation Area. The fight has continued for decades to designate the Boulder-White Clouds a Wilderness Area. I personally think it rivals the Sawtooths as my favorite backpacking destination in Idaho and I’ve set foot in most mountain ranges save a few in the panhandle. A view near the lower section of trail on the way to Walker Lake Itinerary Wednesday – Drive 4 hours from Boise; less than a mile hike to Jimmy Smith Lake; Backpack 6 to 7 miles to Walker Lake (camp).