Complete Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vector » Email: [email protected] Features, Editorial and Letters the Critical Journal of the BSFA Andrew M

Sept/Oct 1998 £2.25 David Wingrove • John Meaney The Critical Tetsuo and Tetsuo II • Gattaca • John Wyndham Journal of George Orwell • Best of British Poll • Dr Who the BSFA Editorial Team Production and General Editing Tony Cullen - 16 Weaver's Way, Camden, London NW1 OXE Vector » Email: [email protected] Features, Editorial and Letters The Critical Journal of the BSFA Andrew M. Butler - 33 Brook View Drive, Keyworth, Nottingham, NG12 5JN Email: [email protected] Contents Gary Dalkin - 5 Lydford Road, Bournemouth, 3 Editorial - The View from Hangar 23 Dorset, BH11 8SN by Andrew Butler Book Reviews 4 TO Paul Kincaid 60 Bournemouth Road, Folkestone, Letters to Vector Kent CT19 5AZ 5 Red Shift Email: [email protected] Corrections and Clarifications Printed by: 5 Afterthoughts: Reflections on having finished PDC Copyprint, 11 Jeffries Passage, Guildford, Chung Kuo Surrey GU1 4AP .by David Wingrove |The British Science Fiction Association Ltd. 6 Emergent Property An Interview with John Meaney by Maureen Kincaid Limited by guarantee. Company No. 921500. Registered Speller Address: 60 Bournemouth Road, Folkestone, Kent. CT19 5AZ 9 The Cohenstewart Discontinuity: Science in the | BSFA Membership Third Millennium by lohn Meaney UK Residents: £19 or £12 (unwaged) per year. 11 Man-Sized Monsters Please enquire for overseas rates by Colin Odell and Mitch Le Blanc 13 Gattaca: A scientific (queer) romance Renewals and New Members - Paul Billinger , 1 Long Row Close , Everdon, Daventry, Northants NN11 3BE by Andrew M Butler 15 -

Why Hollywood Isn't As Liberal As We Think and Why It Matters

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2019 Why Hollywood Isn't As Liberal As We Think nda Why It Matters Amanda Daily Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Daily, Amanda, "Why Hollywood Isn't As Liberal As We Think nda Why It Matters" (2019). CMC Senior Theses. 2230. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/2230 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Claremont McKenna College Why Hollywood Isn’t As Liberal As We Think And Why It Matters Submitted to Professor Jon Shields by Amanda Daily for Senior Thesis Fall 2018 and Spring 2019 April 29, 2019 2 3 Abstract Hollywood has long had a reputation as a liberal institution. Especially in 2019, it is viewed as a highly polarized sector of society sometimes hostile to those on the right side of the aisle. But just because the majority of those who work in Hollywood are liberal, that doesn’t necessarily mean our entertainment follows suit. I argue in my thesis that entertainment in Hollywood is far less partisan than people think it is and moreover, that our entertainment represents plenty of conservative themes and ideas. In doing so, I look at a combination of markets and artistic demands that restrain the politics of those in the entertainment industry and even create space for more conservative productions. Although normally art and markets are thought to be in tension with one another, in this case, they conspire to make our entertainment less one-sided politically. -

The City of Prague Philharmonic Orchestra and Chorus

WINTER 2017 - SPRING 2018 NEWS www.tadlowmusic.com THE CITY OF PRAGUE PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA AND CHORUS EUROPE’S MOST EXPERIENCED AND VERSATILE RECORDING ORCHESTRA: 70 YEARS OF QUALITY MUSIC MAKING The CoPPO have been recording local film and TV scores at Smecky Music Studios since 1946, and a large number of international productions since 1988. Over the years they have worked with many famous composers from Europe and America including: ELMER BERNSTEN * MICHEL LEGRAND * ANGELO BADALAMENTI * WOJCIECH KILAR * CARL DAVIS GABRIEL YARED * BRIAN TYLER * RACHEL PORTMAN * MYCHAEL DANNA * JEFF DANNA * NITIN SAWHNEY JAVIER NAVARRETE * LUDOVIC BOURCE * CHRISTOPHER GUNNING * INON ZUR * JOHANN JOHANNSSON * NATHANIEL MECHALY * PATRICK DOYLE * PHILIP GLASS * BEAR McCREARY * JOE HISAISHI In recent years they have continued this tradition of recording orchestral scores for international productions with composers now recording in Prague from: Australia * New Zealand * Japan * Indonesia * Malaysia * Singapore * China * Taiwan * Russia * Egypt * The Lebanon * Turkey * Brazil * Chile and India PRAGUE HAS BECOME THE CENTRE OF WORLDWIDE SCORING AND ORCHESTRAL RECORDINGS BECAUSE BEING 100% TOTAL BUYOUT ON ALL RECORDINGS AND THE QUALITY OF FINE MUSICIANS AND RECORDING FACILITIES TADLOW MUSIC The Complete Recording Package for FILM, TV, VIDEO GAMES SCORING AND FOR THE RECORD INDUSTRY in LONDON + PRAGUE Music Contractor / Producer : James Fitzpatrick imdb page: http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0280533/ NEW PHONE # : +44 (0) 797 181 4674 “It’s an absolute delight to work with Tadlow Music. The Prague musicians are great and I’ve had many happy experiences recording with them.” - Oscar Winning Composer RACHEL PORTMAN “Always a pleasure to work with James, as i have many times over the years. -

Fafnir Cover Page 1:2018

NORDIC JOURNAL OF SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY RESEARCH Volume 5, issue 1, 2018 journal.finfar.org The Finnish Society for Science Fiction and Fantasy Research Suomen science fiction- ja fantasiatutkimuksen seura ry Submission Guidelines Fafnir is a Gold Open Access international peer-reviewed journal. Send submissions to our editors in chief at [email protected]. Book reviews, dissertation reviews, and related queries should be sent to [email protected]. We publish academic work on science-fiction and fantasy (SFF) literature, audiovisual art, games, and fan culture. Interdisciplinary perspectives are encouraged. In addition to peer- reviewed academic articles, Fafnir invites texts ranging from short overviews, essays, interviews, conference reports, and opinion pieces as well as academic reviews for books and dissertations on any suitable SFF subject. Our journal provides an international forum for scholarly discussions on science fiction and fantasy, including current debates within the field. Open-Access Policy All content for Fafnir is immediately available through open access, and we endorse the definition of open access laid out in Bethesda Meeting on Open Access Publishing. Our content is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License. All reprint requests can be sent to the editors at Fafnir, which retains copyright. Editorial Staff Editors in Chief Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay Laura E. Goodin Aino-Kaisa Koistinen Reviews Editor Dennis Wilson Wise Managing Editor Jaana Hakala Advisory Board Merja Polvinen, University of Helsinki, Chair Sari Polvinen, University of Helsinki Paula Arvas, University of Helsinki Liisa Rantalaiho, University of Tampere Stefan Ekman, University of Gothenburg Adam Roberts, Royal Holloway, U. London Ingvil Hellstrand, University of Stavanger Hanna-Riikka Roine, U. -

Danny Boyle Himesh Patel, Lily James

UNIVERSAL PICTURES présente En association avec PERFECT WORLD PICTURES Une production WORKING TITLE Un fi lm de DANNY BOYLE HIMESH PATEL, LILY JAMES, avec ED SHEERAN et KATE MCKINNON Producteurs délégués NICK ANGEL, LEE BRAZIER, LIZA CHASIN Produit par, TIM BEVAN, ERIC FELLNER, MATTHEW JAMES WILKINSON, BERNARD BELLEW, RICHARD CURTIS, DANNY BOYLE Sur une idée originale de JACK BARTH et RICHARD CURTIS Scénario RICHARD CURTIS SORTIE : 3 JUILLET Durée 1h56 Matériel disponible sur www.upimedia.com Yesterday-lefi lm.com @Yesterday.lefi lm @UniversalFR #Yesterday DISTRIBUTION PRESSE Universal Pictures International Sylvie FORESTIER 21, rue François 1er Giulia GIÉ 75008 Paris assistées de Sophie GRECH Tél. : 01 40 69 66 56 www.universalpictures.fr SYNOPSIS Hier tout le monde connaissait les Beatles, mais aujourd’hui seul Jack se souvient de leurs chansons. Il est sur le point de devenir extrêmement célèbre. Jack Malik (Himesh Patel) est un auteur-compositeur interprète en galère, dont les rêves sont en train de sombrer dans la mer qui borde le petit village où il habite en Angleterre, en dépit des encouragements d’Ellie (Lily James), sa meilleure amie d’enfance qui n’a jamais cessé de croire en lui. Après un accident avec un bus pendant une étrange panne d’électricité, Jack se réveille dans un monde où il découvre que les Beatles n’ont jamais existé… ce qui va le mettre face à un sérieux cas de conscience. Poussé par Debra (Kate McKinnon) son agent américain et secondé de son ami Rocky (Joel Fry), roadie improvisé sur le tas, aussi adorable qu’imprévisible, la popularité du jeune homme va vite exploser quand il se met à chanter les titres du groupe le plus connu du monde à un public qui ne les a jamais entendus. -

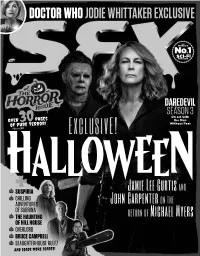

SFX’S Horror Columnist Peers Into If You’Re New to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones Movie

DOCTOR WHO JODIE WHITTAKER EXCLUSIVE SCI-FI 306 DAREDEVIL SEASON 3 On set with Over 30 pages the Man of pure terror! Without Fear featuring EXCLUSIVE! HALLOWEEN Jamie Lee Curtis and SUSPIRIA CHILLING John Carpenter on the ADVENTURES OF SABRINA return of Michael Myers THE HAUNTING OF HILL HOUSE OVERLORD BRUCE CAMPBELL SLAUGHTERHOUSE RULEZ AND LOADS MORE SCARES! ISSUE 306 NOVEMBER Contents2018 34 56 61 68 HALLOWEEN CHILLING DRACUL DOCTOR WHO Jamie Lee Curtis and John ADVENTURES Bram Stoker’s great-grandson We speak to the new Time Lord Carpenter tell us about new OF SABRINA unearths the iconic vamp for Jodie Whittaker about series 11 Michael Myers sightings in Remember Melissa Joan Hart another toothsome tale. and her Heroes & Inspirations. Haddonfield. That place really playing the teenage witch on CITV needs a Neighbourhood Watch. in the ’90s? Well this version is And a can of pepper spray. nothing like that. 62 74 OVERLORD TADE THOMPSON A WW2 zombie horror from the The award-winning Rosewater 48 56 JJ Abrams stable and it’s not a author tells us all about his THE HAUNTING OF Cloverfield movie? brilliant Nigeria-set novel. HILL HOUSE Shirley Jackson’s horror classic gets a new Netflix treatment. 66 76 Who knows, it might just be better PENNY DREADFUL DAREDEVIL than the 1999 Liam Neeson/ SFX’s horror columnist peers into If you’re new to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones movie. her crystal ball to pick out the superhero shows, this third season Fingers crossed! hottest upcoming scares. is probably a bad place to start. -

Emmy Award Winners

CATEGORY 2035 2034 2033 2032 Outstanding Drama Title Title Title Title Lead Actor Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Outstanding Comedy Title Title Title Title Lead Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Outstanding Limited Series Title Title Title Title Outstanding TV Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actor—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title CATEGORY 2031 2030 2029 2028 Outstanding Drama Title Title Title Title Lead Actor—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Outstanding Comedy Title Title Title Title Lead Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. -

Vector 8 the CRITICAL JOURNAL of the BSFA £2.25 August 1996

1 8 Vector 8 THE CRITICAL JOURNAL OF THE BSFA £2.25 August 1996 Bob Shaw 1931-1996 also, Books of the Vear - 1995 & The Science of The Time Machine EDITORIAL INVECTIVE Before the modern era of semi-mainstream acceptance, which is to say before Star Wa n, things were simple. Bookshops were stocked with, in random orde r, Asimov, Ellison, Heinlein, Clarke, Watson, Cowpcr, Priest, Roberts, Coney, Holdstock, Moorcock, Simak, Wyndham, Farmer, Shcc klcy, Bester, Anckrson [Poul], Bradbury, Ballard, Delany, Contents LcGuin, We ll s, Blish, Dick, Zclazny. The only fantasy not in the 3 Bob Shaw 193 1-1996 Children's section was The l...lJrd of the Rings and a few titles in the BoSh remembered and apprcciatc-d by Ballantine Adult Fantasy se ri es. [not what it means today.] Dave Langford, Andy Sawyer, Post-Star Wan everything changed Skl r Trtk returned. D1m,geons and Brian Stableford, and J ames White Dragons spawned an industry, created a new hobby and, eventually, a publishing catagory. Media novelisations went nova, and an entire Year- 1995 Books of the genre, High Fantasy, was born from the continuing enthusiasm for Vector Reviewers pick their favourites, one book: the aforementioned l...lJrd of/he Rings. edited by Paul Kincaid Today many of the above writers have vanished from the shops. Some 12 Cognitive Mapping 3: Aliens as part of the process of the old making way for the new, but others by Paul Kincaid because of the demand for shelf space created by the new forms of publishing- the book of the calendar of the T-shirt of the recipe book 14 WIid Extravagant Theories of the CD-ROM of the RPG of the video of the Theatrical Motion The Science of Tlu Time Machine, by Picture of the 1V show of the comic book, etc. -

Gender, Society and Technology in Black Mirror

Aditya Hans Prasad WGSS 7 Professor Douglas Moody May 2018. Gender, Society and Technology in Black Mirror The anthology television show Black Mirror is critically acclaimed for the manner in which it examines and criticizes the relationship between human society and technology. Each episode focuses on a specifically unnerving aspect of technology, and the topics explored by it range from surveillance to mass media. These episodes may initially provide a cynical perspective of technology, but they are far more nuanced in that they provide a commentary on how human technology reflects the society it is produced for and by. With that in mind, it is evident that Black Mirror is an anthology series of speculative fiction episodes that scrutinizes the darker implications of these technologies. Often, these implications are products of particular social constructs such as race, socioeconomic class and gender. It is particularly interesting to analyze the way in which Black Mirror presents the interaction between gender and technology. Many of the television show’s episodes highlight the differences in the way women interact with technology as compared to men. These intricacies ultimately provide viewers with an understanding of the position women often hold in a modern, technologically driven society. Black Mirror is renowned for the unsettling way it presents the precarious situations that come up when technology begins to reflect the flaws of a society. The episode “Fifteen Million Merits” explores, among other things, the hyper-sexualized nature of modern mass media. The episode takes place in a simulated world, where humans exist inside a digital world where all they do is cycle to earn credits, spend credits on products of the media and sleep. -

Anticipatory Knowledge on Post-Scarcity Futures in John Barnes's Thousand Cultures Tetralogy

After Work: Anticipatory Knowledge on Post-Scarcity Futures in John Barnes’s Thousand Cultures Tetralogy By Michael Godhe Abstract What would happen if we could create societies with an abundance of goods and services created by cutting-edge technology, making manual wage labour unne- cessary – what has been labelled societies with a post-scarcity economy. What are the pros and cons of such a future? Several science fiction novels and films have discussed these questions in recent decades, and have examined them in the so- cio-political, cultural, economic, scientific and environmental contexts of globa- lization, migration, nationalism, automation, robotization, the development of nanotechnology, genetic engineering, artificial intelligence and global warming. In the first section of this article, I introduce methodological approaches and theoretical perspectives connected to Critical Future Studies and science fiction as anticipatory knowledge. In the second and third section, I introduce the question of the value of work by discussing some examples from speculative fiction. In sec- tion four to seven, I analyze the Thousand Culture tetralogy (1992–2006), written by science fiction author John Barnes. The Thousand Cultures tetralogy is set in the 29th century, in a post-scarcity world. It highlights the question of work and leisure, and the values of each, and discusses these through the various societies depicted in the novels. What are the possible risks with societies where work is voluntary? Keywords: post-scarcity, work, utopia, dystopia, critical future studies Godhe, Michael: “After Work: Anticipatory Knowledge on Post-Scarcity Futures in John Barnes’s Thousand Cultures tetralogy”, Culture Unbound, Volume 10, issue 2, 2018: 246–262. -

Honors in Practice, Volume 16 (Complete)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Honors in Practice -- Online Archive National Collegiate Honors Council 2020 Honors in Practice, Volume 16 (complete) Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nchchip Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, Higher Education Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, and the Other Education Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Collegiate Honors Council at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors in Practice -- Online Archive by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. In This Issue Volume 16 | 2020 Honors In Practice 2019 PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS Radical Honors: Pedagogical Troublemaking as a Model for Institutional Change Richard Badenhausen ESSAYS Music in the Holocaust as an Honors Colloquium Galit Gertsenzon HIP Brave New Worlds: Transcending the Humanities/STEM Divide through Creative Writing Adam Watkins and Zahra Tehrani Humanities-Driven STEM—Using History as a Foundation for HIP STEM Education in Honors Honors In Practice John Carrell, Hannah Keaty, and Aliza Wong A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL COLLEGIATE HONORS COUNCIL Best Practices in Honors Pedagogy: Teaching Innovation and Community Engagement through Design Thinking Beth H. Chaney, Tim W. Christensen, Alleah Crawford, Katherine Ford, W. Wayne Godwin, Gerald Weckesser, Todd Fraley, and Volume 16 | 2020 Phoenix Little Teaching Critical University Studies: A First-Year Seminar to Cultivate Intentional Learners Elizabeth Bleicher A Potential for Improving Honors Retention with Degree Planning Teddi S. Deka A Meaningful and Useful Twofer: Enhancing Honors Students’ Research Experiences While Gathering Assessment Data Mary Scheuer Senter Statistics: A Cautionary Tale Len Zane Contracts for Honors Credit: Balancing Access, Equity, and Opportunities for Authentic Learning Patrick Bahls BRIEF IDEAS ABOUT WHAT WORKS IN 16 Volume HONORS Authors: Brent M. -

Black Mirrors: Reflecting (On) Hypermimesis

Philosophy Today Volume 65, Issue 3 (Summer 2021): 523–547 DOI: 10.5840/philtoday2021517406 Black Mirrors: Reflecting (on) Hypermimesis NIDESH LAWTOO Abstract: Reflections on mimesis have tended to be restricted to aesthetic fictions in the past century; yet the proliferation of new digital technologies in the present century is currently generating virtual simulations that increasingly blur the line between aes- thetic representations and embodied realities. Building on a recent mimetic turn, or re-turn of mimesis in critical theory, this paper focuses on the British science fiction television series, Black Mirror (2011–2018) to reflect critically on the hypermimetic impact of new digital technologies on the formation and transformation of subjectivity. Key words: mimesis, Black Mirror, simulation, science fiction, hypermimesis, AI, posthuman he connection between mirrors and mimesis has been known since the classical age and is thus not original, but new reflections are now appearing on black mirrors characteristic of the digital age. Since PlatoT first introduced the concept ofmimēsis in book 10 of the Republic, mir- rors have been used to highlight the power of art to represent reality, generating false copies or simulacra that a metaphysical tradition has tended to dismiss as illusory shadows, or phantoms, of a true, ideal and transcendental world. This transparent notion of mimesis as a mirror-like representation of the world has been dominant from antiquity to the nineteenth century, informs twentieth- century classics on realism,