Vol. 14 No. 3 (1999, Pp. 3-24) Migration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2018 AL HAJ NUR MOHAMMED Chairman, Jamuna Bank Foundation

Annual Report 2018 AL HAJ NUR MOHAMMED Chairman, Jamuna Bank Foundation 224 Jamuna Bank A Few Words from rhe Chairman Jamuna Bank Foundation Dear Stakeholders, Kishoregonj district by Jamuna Bank Foundation. Char Tertakia is the remote char area where no electricity is Asslamu Alikum. available, many poor & meritorious students of the village could not study well due to cost of kerosene oil etc. We Jamuna Bank Foundation has been playing pioneer role have arranged Solar light for every family in this village. in the CSR activities since its inception. The vision of the Henceforth, the students of that village can study at night by Foundation is to advance a more purpose-led and values- using solar light, the villagers can perform evening chores driven supportive approach to helping solve society’s continuously and without any interruption. greatest challenges in education and humanitarianism. Since establishing the Foundation, we’ve endeavored to be a We have completed the construction works of 2 story out catalyst for change. of 10 storied building of Jamuna Bank Old home at Mekail Nagar, Keranigonj to accommodate enlightened, renowned In 2018, we launched Jamuna Bank Foundation Kidney and respectable aged people who once upon a time Dialysis Center for providing dialysis services to the patients contributed to the development of society to Nation and at a minimum cost and free dialysis for poor patient. now have become desolated and helpless with the increase Organized 18 free medical camps throughout the country & of Unitarian family in course of time. It is a non-profitable at Bishwa Ijtema where 81,446 no. -

In the Supreme Court of Bangladesh High Court Division (Special Original Jurisdiction)

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BANGLADESH HIGH COURT DIVISION (SPECIAL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION) Writ Petition No. 696 of 2010 In the matter of: An application under Article 102(2)(a)(ii) of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh And In the matter of: Siddique Ahmed. ... Petitioner -Versus- Bangladesh, represented by the Secretary Ministry of law, justice and Parliamentary Affairs, Bangladesh Secretariat, P.S.-Ramna and District-Dhaka and others. ....Respondents Mr. Mirza Ali Mahmood, Advocate. ...For the petitioner Mr. Mahbubey Alam, Attorney General Mr.Akram Hossain Chowdhury Mr.Karunamoy Chakma Mr.Bhisma Dev Chakravarty Ms.Promila Biswas Ms.Shakila Rowshan Jahan Deputy Attorneys General Mr.Ekramul Haque Md.Diliruzzaman Ms. Kasifa Hossain Assistant Attorneys General And Mr.M.K.Rahman, Additional Attorney General with Mr.Mostafa Zaman Islam Deputy Attorney General Mr.S.M.Nazmul Huq Assistant Attorney General ... For respondent no.1. Mr. Murad Reza, Additional Attorney General with Mr. Md. Nazrul Islam Talukder Mr. Md. Motaher Hossain Sazu, =2= Mr. M. Khurshid Alam sarker, Mr. Mahammad Selim .... Deputy Attorneys General Mr. Delowar Hossain Samaddar, A.A.G Mr. A.B.M. Altaf Hossain, A.A.G Mr. Amit Talukder, A.A.G Mr. Md. Shahidul Islam Khan, A.A.G Ms. Purabi Saha, A.A.G Ms. Fazilatunessa Bappy, A.A.G ... For the respondents No.2 Mr. M. Amir-Ul Islam, Senior Advocate Mr. A.F.M. Mesbahuddin, Senior Advocate Mr. Abdul Matin Khasru, Senior Advocate Mr. Yusuf Hossain Humayun, Advocate ......As Amicus Curiae Heard on 08.07.10, 26.07.10, 27.07.10, 10.08.10, 16.08.10, 25.8.10 and Judgment on 26.08.2010 . -

Send Us Victorious N Zeeshan Khan World

MONDAY, DECEMBER 16, 2013 | www.dhakatribune.com Victory Day 2013 Illustration: Sabyasachi Mistry Send us victorious n Zeeshan Khan world. The economic exploitation was our surprise when our language, our When Babur, the Mughal, encoun- Charjapadas. It ran through the Pala acute, resulting in death by the mil- culture, our ethnicity, our economy tered this kingdom for the first time, and Sena kingdoms of Gaur-Bongo to or the generations born lions, but the strains on our social and and then ultimately our votes were in the 1500s he made this observation: the Vangaladesa of the Cholas and was after December 16, 1971, psychological well-being were equally subordinated to a national pecking reborn in the Sultanate of Bangala that Bangladesh was an exis- catastrophic. Added to that, a British order that placed us at the bottom. A “There is an amazing custom in Babur encountered. tentially “normal” place policy of advancing some communi- rude awakening followed, and then Bengal: rule is seldom achieved by The emergence of Bangladesh was to grow up in. Nothing in ties at the expense of others created the guns came out. hereditary succession. Instead, there a historical inevitability. Repeatedly, Fthe atmosphere hinted at the violent sectarian tensions that wouldn’t go Truth is, the break from Pakistan, is a specific royal throne, and each the people of this land have resist- upheavals our preceding generations away when 1947 rolled around. even from India earlier, was the of the amirs, viziers or office holders ed authority that was oppressive or had to contend with and there was But an independent Bengal was in has an established place. -

Impacts of the Rohingya Refugee Influx on Host Communities

Impacts of the Rohingya Refugee November 2018 Impacts of the Rohingya Refugee Influx on Host Communities November 2018 United Nations Development Programme www.bd.undp.org United Nations Development Programme UN Offices, 18th Floor, IDB Bhaban Agargaon, Sher-e-Bangla Nagar Dhaka 1207, Bangladesh www.bd.undp.org Standard Disclaimer: This report is a product of the UNDP Bangladesh Country Office. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Board of the UNDP or the governments they represent. UNDP does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of UNDP concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Copyright Statement: Copyright © United Nations Development Programme, Bangladesh Country Office UN Offices, 18th Floor, IDB Bhaban, Agargaon, Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka 1207, Bangladesh Table of Contents Figures, tables and boxes IV CHAPTER 4 36 Acknowledgement VIII The Rohingya influx, GoB response and institutional set-up Acronyms IX 4.1. The refugee population profile 37 Executive summary 1 4.1.1. Definition 37 4.1.2. Previous inflows, repatriation and CHAPTER 1 16 37 remaining refugees Introduction 4.1.3. The latest influx 37 4.1.4. Demographic and other characteristics 37 CHAPTER 2 18 of refugees 4.2. Bangladesh government policy on the Rationale and methodology 39 Rohingya and response 2.1. Rationale 18 4.3. Organizational framework for the refugee 42 2.2. -

Al-Haj Nur Mohammed Founder Chairman, Jamuna Bank Foundation Jamuna Bank Annual Report 2017 199

Corporate Social Responsibility Jamuna Bank 196 Annual Report 2017 CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY JAMUNA BANK FOUNDATION Why Corporate Social Responsibility? CSR refers to strategies corporations Corporate social responsibility (CSR) refers to strategies corporations or firms conduct their business in a way that is or firms conduct their business in a ethical, society friendly and beneficial to community in terms way that is ethical, society friendly of development. Business is basically a socio-economic entity. and beneficial to community in Although business is fundamentally an economic activity, it cannot be carried out in isolation of society. It is a group terms of development endeavour and therefore has a number of responsibilities towards different stakeholders – management, workers, customers, shareholders, government and the society. Today, the world faces lot of challenges ranging from Realisation and fulfilment of responsibilities towards these environmental degradation through poverty and human stakeholders is termed as corporate social responsibilities. rights, to energy and resource supply issues. Our social Further, business cannot function independently and responsibility policy focuses on using our capabilities as a depends on the society for various requirements. Business is business to improve lives and sustain our planet through a part of the society and has to follow and operate within the contributions to local communities and society at large. limits of the rules and regulations prescribed by the society. It Corporate Social Responsibility is not only an act for is the responsibility of the business to provide fair wages and humanity but also to provide good working environment facilities to its employees, provide a fair return on shareholders’ to an organization’s employees, to pay just remuneration, funds, pay taxes and duties regularly and contribute to social to give regular leave, to care as a human beings and to care development in which it is prospering. -

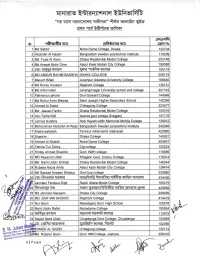

16R{19Ffiebffie'

:16r{19ffieBffiE' "qg {[6{ <tqEtmrt{ -ilftEs'f" tr-s q{flt{ AtT ereN "rr(tfr"fmrvtfu$t ,gq,{qf8 gGtrffi{{rq SI "r-ftr,Etaqrq GtI6r {i 1 Md Sabbir Notre Dame Colleqe, Dhaka 122734 2 Abdullah Al Hasan Banqladesh sweden polvtechnic lnstitute 115239 J Md. Fuad AlAlam Dhaka Residential Model Colleqe 203148 4 Md.Anayet Kobir Ome Abdul Kadir Mollah Citv Colleqe 1 99088 5 Cil3 IIIIGI<-{NF[ uqqrrrcF-osrdrq 105174 b MD.ABDUR RAHIM BADSHA DHAKA COLLEGE 228119 7 Masum Billah Jurainpur Adarsha U niversity College 168440 B Md.Rockv Hossain Raishahi Colleoe 1351 31 I Md Ariful lslam Jahanqirnaoar Universitv school and colleqe 307743 10 Fatima tus iahara Govt Edward Colleqe 144048 11 Md RuhulAmin Biswas Saint Joseph Hiqher Secondary School 142356 12 Ahmed Al Sabid Chittaoono Colleoe 223577 13 Md. Jeesan Fardin Dhaka Residential Model Colleqe 1 50316 14 Abu Talha Rafi lslamia qovt colleqe,Siraiqani 147176 15 Lamiya Sultana Hazi Kevamuddin Memorial Mohila Colleqe 128912 16 Mohammad Abdullah Al Reaz Banqladesh Sweden polytechnic lnstitute 242046 17 Khalid saifullah Ta'mirul millat kamil madrasah 422660 18 Shamim Dhaka Colleqe 140261 19 Ahmed Al Shahik Notre Dame Colleqe 505801 20 Fatima TuzZohra Ctg college 120224 21 Hridav Ahmed Shadhin Govt. KMH colleqe 1 1 8985 22 MD Neyamot Ullah Khilqaon Govt. Colonv Colleqe 178314 23 Md. Naim Uddin Shihab Dhaka Residential Model Colleqe 148344 24 Rubaba Nazia Anita Abdul kadir Mollah Citv Colleqe 136474 25 Md Sazzad Hossan Shabuz Govt kup colleqe 230880 ,$ -26 mrc frq'erH 5fir<F'K \Il\9tq<il\9 e.railt\Blt {tqht}il atI\crt \thflrl 434456 Jannatul Ferdous Dipti Raiuk Uttara Model College 155219 flP q1s4 -c9a Rne{rta{s 1r <uil;[ frfrffTT s"rR-4 nl'Grlqr, SFI{[ 428858 Sr,o F2e Md.Jannatul Nayeem Dhaka Citv Colleqe 208456 FJ 30 MD. -

Remittance Endeavour Progress

Annual Report 2020 INVESTMENT ADVANCEMENT DEPOSITSDEPOSITS GDP GROWTH TRUST GDP SME REMITTANCE ENDEAVOUR PROGRESS Annual Report 2020 1 2 Annual Report 2020 Annual Report 2020 Annual Report 2020 3 Allah has permitted trading and forbidden (Riba) usury. Surah 2 Al-Bakara-275 6 Annual Report 2020 PAGE OF CONTENTS Qur’anic Verses on Interest 04 Hadith on Interest 05 Opinion of other Religions and Great Men on Interest 06 Board of Directors 07 Allah has permitted trading Executive Committee, Audit Committee, Shariah Supervisory Committee 08 Management Team 09 and forbidden (Riba) usury. Vision, Mission and Commitments 12 Corporate Information 13 Notice of the 26th Annual General Meeting 15 Surah 2 Al-Bakara-275 5 Year Financial Highlights 17 Economic Impact Report 18 Value Added Statements 19 Chairman’s Address 23 Managing Director’s Address 27 Directors’ Report 39 Compliance on the Corporate Governance Code 66 Report of the Shariah Supervisory Committee 83 Implementation Status of Code of Integrity under National Integrity Strategy 85 Report of the Board Audit Committee 87 Activities of the Board Risk Management Committee in the year 2020 89 CEO and CFO’s Declaration to the Board 90 Dividend Distribution Policy 2020 91 Disclosure of Unpaid or Unclaimed Dividend 92 Auditors’ Report & Financial Statements for the year 2020 93 Disclosures on Risk Based Capital (Basel-III) 169 Auditors’ Report on the Financial Statements of AIBL Capital Market Services Limited 2020 187 Auditors’ Report on the Financial Statements of AIBL Capital Management Limited 2020 209 Branches of AIBL 225 Proxy Form 233 Annual Report 2020 7 QUR’aNIC Verses on Interest I am seeking refuge in Allah from Shaitan, the outcast (the cursed one). -

Result of FSIBL Scholarship-2018 Class: HSC to Hon's

Result of FSIBL Scholarship-2018 Class: HSC to Hon’s Sl Name Of Student Class Name Of College / Name Of Guardian Present Address University 1 Ismita Nur Eleven Coxsbazar Govt. Sabe Meraj South Nayapara,Pm College Khali,Coxsbazar 2 Md Sajedul Islam Eleven Joypurhat Anowar Hossen Atol, Joypurhat Govt.College 3 Md. Akharuzzaman Hons (2rd Rajshahi University Md. Mahbubur Shahid Shahrardy Hall, Year) Rahman Rajshahi University, Rajshahi 4 Md. Mohsin Mia Hons-1st Chittagong Md. Ibrahim Muslimabad,North Year University Patenga,Patenga, Chattogram 5 Md. Sadrul Hon’s 4th Carmical College Md. Mizanur Rahman Balapara Lalbag Rangpur Islam year Rangpur 6 Mowrin Ferdous Eleven Haji Aftab Uddin Abdul Goni Khan Goalbari, Juri Amena Khatun College 7 Nawshat Salam Eleven Ideal School& Late Md.Abdus Slam West Sanarpar, Nuha College Demra,Dhaka 8 Parmita Rashed Eleven Cox's Bazar Govt. Monjura Begum Uttor Mais Para, Eidaon, Chy Naba College Sadar Cox's Bazar. 9 Rasel Mia Hon's (2nd) Dhaka University Izzat Ali Master Da Surjo Sen year Hall, Room No-241. 10 Rihana Rahman Eleven Chandpur Govt. Sahina Rahman Vill:Sengaon,Post:Asikati Mim Mahila College ,Chandpur Sadar 11 Saima Akter Eleven Feni Govt. College Rokeya Begum Patan Bari Road, Feni Sadar, Feni 12 Shinthia Twelve Gazipur Govt Shafiqul Alam Khan Vill: Demra, P.O: Shafiq Puspo Mahila College Taraganj, P.S: Kaliganj, Dist: Gazipur. 13 Shoudia Afrose H.S.C 1st Sonar Bangla Abul Hossain Sardar Vill: Chanda, Post: Year Degree Colege Sonabaria, Kalaroa, Satkhira 14 Sumaiya Jahan Eleven Pabna Govt. Md Abdul Awal Natore Sader, Natore Women College 15 Meraj Ahmed Eleven Shaheed Police Hasina Akter 161,Ahmednogor,Mirpu Smrity School & r-1,Dhaka-1216 College 16 Arif Khan Eleven Barguna Govt Md. -

Judgement 3 Chief Prosecutor V Muhammad Kamaruzzaman

ICT-BD [ICT-2] Case No. 03 of 2012: Judgement 1 Chief Prosecutor v Muhammad Kamaruzzaman International Crimes Tribunal-2 (ICT-2) [Tribunal constituted under section 6 (1) of the Act No. XIX of 1973] Old High Court Building, Dhaka, Bangladesh ICT-BD Case No. 03 of 2012 [Charges: crimes against Humanity and aiding & complicity to commit such crimes as specified in section 3(2)(a)(g)(h) of the Act No. XIX of 1973] The Chief Prosecutor Vs Muhammad Kamaruzzaman Before Justice Obaidul Hassan, Chairman Justice Md. Mozibur Rahman Miah, Member Judge Md. Shahinur Islam, Member For the Prosecution: Mr. Ghulam Arieff Tipoo, Chief Prosecutor Mr. Syed Haidar Ali, Prosecutor Mr. Mohammad Ali, Prosecutor Mr. A.K.M Saiful Islam, Prosecutor Ms. Nurjahan Mukta, Prosecutor Ms. Tureen Afroz, Prosecutor For the Accused: Mr. Abdur Razzak, Senior Advocate, Bangladesh Supreme Court Mr. Kafil Uddin Chowdhury, Advocate, Bangladesh Supreme Court Mr. Ehsan Siddique, Advocate, Bangladesh Supreme Court Date of delivery of Judgment: 09 May 2013 JUDGEMENT [Under section 20(1) of the Act XIX of 1973] I. Opening words Following wrapping up of trial that took place in presence of Muhammad Kamaruzzaman who has been arraigned of internationally recognized crimes i.e. crimes against humanity perpetrated in 1971 in the territory of Bangladesh, ICT-BD [ICT-2] Case No. 03 of 2012: Judgement 2 Chief Prosecutor v Muhammad Kamaruzzaman during the War of Liberation, this Tribunal (ICT-2) [a domestic judicial forum constituted on 22 March 2012 under the International Crimes (Tribunals) Act, 1973] is sitting today to render its unanimous Judgement. -

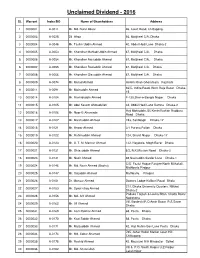

Unclaimed Divident

Unclaimed Dividend - 2016 SL Warrant Index/BO Name of Shareholders Address 1 0000001 A-0011 Mr. Md. Nurul Absar 46, Court Road, Chittagong. 2 0000003 A-0025 Dil Afroz 66, Motijheel C/A, Dhaka 3 0000004 A-0048 Mr. Taslim Uddin Ahmed 40, Abdul Hadi Lane Dhaka-2 4 0000005 A-0053 Mr. Khondker Mahtab Uddin Ahmed 67, Motijheel C/A. Dhaka 5 0000006 A-0054 Mr. Khondker Raisuddin Ahmed 67, Motijheel C/A. Dhaka 6 0000007 A-0055 Mr. Khondker Raziuddin Ahmed 67, Motijheel C/A. Dhaka 7 0000008 A-0056 Mr. Khondker Giasuddin Ahmed 67, Motijheel C/A. Dhaka 8 0000009 A-0074 Mr. Murad Ahmed Hetem Khan Ghoramara Rajshahi 66/C, Indira Road, West Raja Bazar Dhaka- 9 0000011 A-0091 Mr. Moinuddin Ahmed 15 10 0000014 A-0104 Mr. Rashiduddin Ahmed F-130,Sher-e-Bangla Nagar Dhaka 11 0000015 A-0105 Mr. Abul Kasem Ahmadullah 34, Abdul Hadi Lane Ramna Dhaka-2 Haji Mohiuddin, 56 KiminiVushan Rudduru 12 0000016 A-0106 Mr. Noor-E-Ahameda Road Dhaka 13 0000017 A-0107 Mr. Masihuddin Ahmed 193, Santibagh Dhaka-17 14 0000018 A-0121 Mr. Anwar Ahmed 3/1 Purana Paltan Dhaka 15 0000019 A-0122 Mr. Rahimuddin Ahmed 124, Shanti Nagar Dhaka-17 16 0000020 A-0123 Mr. A. T. M. Mansur Ahmed 132, Nayatola, Mogh Bazar Dhaka 17 0000021 A-0131 Mr. Ghiasuddin Ahmed 8/2, R.K.Mission Road Dhaka-3 18 0000023 A-0141 Mr. Nazir Ahmed 48,Nasiruddin Sardar Lane Dhaka-1 C/O. Fazlul Haque Farajee North Mithakali, 19 0000024 A-0146 Mr. -

2019 Centre Wise Final College List ======Zilla : 15 - Nawabganj ======Centre Centre College College Name Code Name Code ======151 - Nawabganj-1 No

BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, RAJSHAHI H. S. C. EXAMINATION - 2019 CENTRE WISE FINAL COLLEGE LIST ============================== ZILLA : 10 - RAJSHAHI ================================================================================ CENTRE CENTRE COLLEGE COLLEGE NAME CODE NAME CODE ================================================================================ 101 - RAJSHAHI-1 NO. OF COLLEGE = 1 ----------------------------------------------------------------- 1075 - RAJSHAHI GOVT. CITY COLLEGE -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ================================================================================ CENTRE CENTRE COLLEGE COLLEGE NAME CODE NAME CODE ================================================================================ 102 - RAJSHAHI-2 NO. OF COLLEGES = 2 ----------------------------------------------------------------- 1005 - RAJSHAHI COLLEGIATE SCHOOL AND COLLEGE ----------------------------------------------------------------- 1025 - NEW GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE, RAJSHAHI -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ================================================================================ CENTRE CENTRE COLLEGE COLLEGE NAME CODE NAME CODE ================================================================================ 103 - RAJSHAHI-3 NO. OF COLLEGE = 1 ----------------------------------------------------------------- 1050 - RAJSHAHI GOVT. WOMEN'S COLLEGE -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

English Translation from The

CultureTalk Bangladesh Video Transcripts: http://langmedia.fivecolleges.edu The Assassination of Intellectuals English translation: We have obtained our beloved independence at the cost of thousands of lives. The martyrs of the nine month-long independence war in 1971 include farmers, laborers, students, professors, members of the armed forces, civil servants, men and women from various professions, children, and countless other people whose names are unknown. The people of this country are proud of them. The merciless attack on the innocent people of Dhaka began late at night on the 25 th of March, 1971. Pakistani soldiers launched the surprise attack and [consequent] bloodbath at around midnight. At first they killed anybody and everybody, and then carried out the planned and cold-blooded murder of the famous and respected people of this country. They prepared a death-list containing the names of talented people in different professions throughout the country – both within Dhaka and outside of Dhaka. They realized their murderous intentions using great cruelty, using the help of people in the country who opposed independence … independence. At midnight on the 25 th of March, they attacked the student dorms in Dhaka University and the residences of professors. M. Muniruzzaman was a deeply religious professor of science at Dhaka University. Upon hearing tremendous firing, he [anticipated the worst]. He had sat down to read the Holy Qur’an. The Pakistani soldiers seized him as he was, and dragged him away. The renowned professor of English, Jyotirmoy Guhathakurata lived downstairs in the same building. The raiding party took him away also. After this, the soldiers took them downstairs and shot them.