Supreme Court of Canada Citation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Report on the Screen-Based

PROFILE ECONOMIC REPORT ON THE SCREEN-BASED MEDIA PRODUCTION INDUSTRY IN CANADA 2019 PROFILE ECONOMIC REPORT ON THE SCREEN-BASED MEDIA PRODUCTION INDUSTRY IN CANADA 2019 Prepared for the Canadian Media Producers Association, Department of Canadian Heritage, Telefilm Canada and Association québécoise de la production médiatique Production facts and figures prepared by Nordicity Group Ltd. Profile 2019 is published by the Canadian Media Producers Association (CMPA) in collaboration with the Department of Canadian Heritage, Telefilm Canada, the Association québécoise de la production médiatique (AQPM) and Nordicity. Profile 2019 marks the 23rd edition of the annual economic report prepared by CMPA and its project partners over the years. The report provides an analysis of economic activity in Canada’s screen-based production sector during the period April 1, 2018 to March 31, 2019. It also provides comprehensive reviews of the historical trends in production activity between fiscal years 2009/10 to 2018/19. André Adams-Robenhymer Policy Analyst, Film and Video Policy and Programs Ottawa Susanne Vaas Department of Canadian Mohamad Ibrahim Ahmad 251 Laurier Avenue West, 11th Floor Vice-President, Heritage Statistics and Data Analytics Ottawa, ON K1P 5J6 Corporate & International Affairs 25 Eddy Street Supervisor, CAVCO Gatineau, QC K1A 0M5 Tel: 1-800-656-7440 / 613-233-1444 Nicholas Mills Marwan Badran Email: [email protected] Director, Research Tel: 1-866-811-0055 / 819-997-0055 Statistics and Data Analytics cmpa.ca TTY/TDD: 819-997-3123 Officer, CAVCO Email: [email protected] Vincent Fecteau Toronto https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian- Senior Policy Analyst, 1 Toronto Street, Suite 702 heritage.html Film and Video Policy and Programs Toronto, ON M5C 2V6 Mounir Khoury Tel: 1-800-267-8208 / 416-304-0280 The Department of Canadian Senior Policy Analyst, Email: [email protected] Heritage contributed to the Film and Video Policy and Programs funding of this report. -

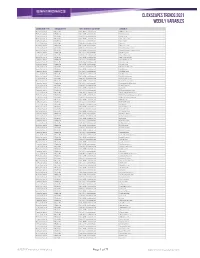

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

15383 Onex Q2 MDA.Qxd

Management’s Discussion and Analysis and Financial Statements Second Quarter Ended June 30, 2006 ONEX CORPORATION Onex manages third party private equity investments through the Onex Partners and ONCAP family of funds and invests in real estate and public equities through Onex Real Estate Partners and Onex Capital Management. It generates annual management fee income and earns a carried interest on more than $3.5 billion of third party capital. Onex is a diversified company with annual revenues of approximately $19 billion, assets of $15 billion and 136,000 employees worldwide. It operates through autonomous subsidiaries in a variety of industries, including electronics manufacturing services, aerostructures manufacturing, healthcare, theatre exhibition, customer management services, personal care products and communications infrastructure. Onex is listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange under the symbol OCX. Table of Contents 2 Management’s Discussion and Analysis 22 Consolidated Financial Statements 40 Shareholder Information Throughout this report, all amounts are in Canadian dollars unless otherwise indicated. This report includes Onex Corporation’s Management’s Discussion and Analysis and Financial Statements for the second quarter ended June 30, 2006. We invite you to visit our website, www.onex.com, for your complete and up-to-date source of information about Onex. Get our financial results Get to know our people in a simple, comprehensible Here is what we look for in and the individual format, with interactive businesses we want to own strengths they bring annual and quarterly and what we provide. to our team. financial statements. Find out about See how Onex has our companies. Learn about our operating performed against key Learn about our principles and values, market indices. -

Cineplex Store

Creative & Production Services, 100 Yonge St., 5th Floor, Toronto ON, M5C 2W1 File: AD Advice+ E 8x10.5 0920 Publication: Cineplex Mag Trim: 8” x 10.5” Deadline: September 2020 Bleed: 0.125” Safety: 7.5” x 10” Colours: CMYK In Market: September 2020 Notes: Designer: KB A simple conversation plus a tailored plan. Introducing Advice+ is an easier way to create a plan together that keeps you heading in the right direction. Talk to an Advisor about Advice+ today, only from Scotiabank. ® Registered trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. AD Advice+ E 8x10.5 0920.indd 1 2020-09-17 12:48 PM HOLIDAY 2020 CONTENTS VOLUME 21 #5 ↑ 2021 Movie Preview’s Ghostbusters: Afterlife COVER STORY 16 20 26 31 PLUS HOLIDAY SPECIAL GUY ALL THE 2021 MOVIE GIFT GUIDE We catch up with KING’S MEN PREVIEW Stressed about Canada’s most Writer-director Bring on 2021! It’s going 04 EDITOR’S Holiday gift-giving? lovable action star Matthew Vaughn and to be an epic year of NOTE Relax, whether you’re Ryan Reynolds to find star Ralph Fiennes moviegoing jam-packed shopping online or out how he’s spending tell us about making with 2020 holdovers 06 CLICK! in stores we’ve got his downtime. Hint: their action-packed and exciting new titles. you covered with an It includes spreading spy pic The King’s Man, Here we put the spotlight 12 SPOTLIGHT awesome collection of goodwill and talking a more dramatic on must-see pics like CANADA last-minute presents about next year’s prequel to the super- Top Gun: Maverick, sure to please action-comedy Free Guy fun Kingsman films F9, Black Widow -

2019 Annual Report

2019 Annual Report Stronger together Looking back at 2019 feels like looking back at a world we no longer recognize, but it is an important reminder of the impact Boys and Girls Clubs have on young people, families, and communities—and how our work is even more important in Felix Wu Owen Charters times of crisis. Our ability to adapt, our grit and determination, our shared mission, Board Chair President & CEO vision, and values will guide us through this pandemic. We are stronger together. Support to Clubs remains our priority. Thanks to our partners and significant funding from the Working closely with Clubs, we identified three policy priorities—mental health, child and youth federal government, in 2019 we were able to provide $7.1 million in grants to Clubs. Federal poverty, and youth employment. We continue to be active at all levels of government, successfully funding resulted in three new national programs—Let’s Talk Digital, a collaboration with the advocating for the federal government’s investment in an additional 250,000 before and after Samara Centre for Democracy that engages youth in digital, media, and civic literacy; Creating school spaces across Canada, helping Clubs secure over 700 Canada Summer Jobs grants, and Connections, which establishes safe spaces for teens to talk and learn about substance use, providing training and tools to help 55 Clubs run collective advocacy campaigns. addiction, and mental health; and Great Futures Savings Program, which raises awareness and promotes the Canada Learning Bond. We also worked to strengthen our Reconciliation efforts, including forming a committee with representatives from Clubs and members of our national team to engage our movement and grow Along with the federal government, we continue to see great success with our other strategic our Truth & Reconciliation commitment. -

10 Pm ET, Tuesday, November 10, 2015

For Immediate Release: 10 p.m. ET, Tuesday, November 10, 2015 ANDRÉ ALEXIS WINS THE 2015 SCOTIABANK GILLER PRIZE November 10, 2015 (Toronto, Ontario) – André Alexis has been named the winner of the $100,000 Scotiabank Giller Prize for Fifteen Dogs, published by Coach House Books. The announcement was made at a black-tie dinner and award ceremony hosted by Rick Mercer, attended by nearly 500 members of the publishing, media and arts communities. CBC Television is the broadcaster for the gala. This year the prize celebrates its twenty-second anniversary. A shortlist of five authors and their books was announced on October 5, 2015. Those finalists are: André Alexis for his novel Fifteen Dogs, published by Coach House Books Samuel Archibald for his story collection Arvida, published by Biblioasis, translated from the French by Donald Winkler Rachel Cusk for her novel Outline, published by Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd Heather O’Neill for her story collection Daydreams of Angels, published by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd Anakana Schofield for her novel Martin John, published by A John Metcalf Book, an imprint of Biblioasis The shortlist and ultimate winner were selected by the esteemed five-member jury panel made up of Irish author John Boyne (Jury Chair), Canadian writers Cecil Foster, Alexander MacLeod and Alison Pick, and British author Helen Oyeyemi. Of the winning book, the jury wrote: “What does it mean to be alive? To think, to feel, to love and to envy? André Alexis explores all of this and more in the extraordinary Fifteen Dogs, an insightful and philosophical meditation on the nature of consciousness. -

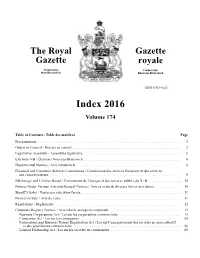

The Royal Gazette Index 2016

The Royal Gazette Gazette royale Fredericton Fredericton New Brunswick Nouveau-Brunswick ISSN 0703-8623 Index 2016 Volume 174 Table of Contents / Table des matières Page Proclamations . 2 Orders in Council / Décrets en conseil . 2 Legislative Assembly / Assemblée législative. 6 Elections NB / Élections Nouveau-Brunswick . 6 Departmental Notices / Avis ministériels. 6 Financial and Consumer Services Commission / Commission des services financiers et des services aux consommateurs . 9 NB Energy and Utilities Board / Commission de l’énergie et des services publics du N.-B. 10 Notices Under Various Acts and General Notices / Avis en vertu de diverses lois et avis divers . 10 Sheriff’s Sales / Ventes par exécution forcée. 11 Notices of Sale / Avis de vente . 11 Regulations / Règlements . 12 Corporate Registry Notices / Avis relatifs au registre corporatif . 13 Business Corporations Act / Loi sur les corporations commerciales . 13 Companies Act / Loi sur les compagnies . 54 Partnerships and Business Names Registration Act / Loi sur l’enregistrement des sociétés en nom collectif et des appellations commerciales . 56 Limited Partnership Act / Loi sur les sociétés en commandite . 89 2016 Index Proclamations Lagacé-Melanson, Micheline—OIC/DC 2016-243—p. 1295 (October 26 octobre) Acts / Lois Saulnier, Daniel—OIC/DC 2016-243—p. 1295 (October 26 octobre) Therrien, Michel—OIC/DC 2016-243—p. 1295 (October 26 octobre) Credit Unions Act, An Act to Amend the / Caisses populaires, Loi modifiant la Loi sur les—OIC/DC 2016-113—p. 837 (July 13 juillet) College of Physicians and Surgeons of New Brunswick / Collège des médecins Energy and Utilities Board Act / Commission de l’énergie et des services et chirurgiens du Nouveau-Brunswick publics, Loi sur la—OIC/DC 2016-48—p. -

Film and Television Production

Produced by the CMPA and the AQPM, in conjunction with the Department of Canadian Heritage. Production facts and figures prepared by Nordicity Group Ltd. Profile 2014 | 1 TITLE GOES HERE The Canadian Media Production Association (CMPA), the Association québécoise de la production médiatique (AQPM), the Department of Canadian Heritage, and Nordicity Group Ltd. have once again collaborated to prepare Profile 2014. Profile 2014 marks the 18th edition of the annual economic report prepared by CMPA and its project partners. Profile 2014 provides an analysis of economic activity in Canada’s screen-based production industry during the period April 1, 2013 to March 31, 2014. It also provides comprehensive reviews of the historical trends in production activity between the fiscal years of 2004/05 and 2013/14. Ottawa Vancouver AQPM 601 Bank Street, 2nd Floor 736 Granville Street, Suite 600 1470 Peel Street, Suite 950, Tower A Ottawa, ON K1S 3T4 Vancouver, BC V6Z 1G3 Montréal, QC H3A 1T1 Tel: 1-800-656-7440 (Canada only)/ Tel: 1-866-390-7639 (Canada only)/ Tel: 514-397-8600 613-233-1444 604-682-8619 Fax: 514-392-0232 Fax: 613-233-0073 Fax: 604-684-9294 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] www.aqpm.ca www.cmpa.ca At the CMPA: At the AQPM: Susanne Vaas Toronto Vice-president, Corporate Marie Collin 160 John Street, 5th Floor and International Affairs President and CEO Toronto, ON M5V 2E5 Tel: 1-800-267-8208 (Canada only)/ Brigitte Doucet 416-304-0280 Deputy General Director Fax: 416-304-0499 Email: [email protected] At the Department of Canadian Heritage: Nordicity Group Ltd. -

Cineplex EA SPORTS NHL14 Premiere Tournament-FINAL.Pdf

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Cineplex, EA SPORTS partner for first-ever giant screen NHL14 tournament Play NHL 14 on a giant theatre screen for the opportunity to win great prizes – days before the game’s official release date Toronto, ON, (TSX: CGX) – September 3, 2013 – Fans of the EA SPORTS NHL hockey franchise will get their first chance to play the newest installment in the series, the award winning, EA SPORTS NHL® 14, live on a huge theatre screen, three days in advance of the game’s official release date. Cineplex Entertainment today announced the opening of registration for the first-ever Cineplex EA SPORTS NHL® 14 Premiere Tournament – beginning at 8:00 a.m. at Toronto’s Cineplex Cinemas Yonge-Dundas, on Saturday, September 7, 2013. “This tournament provides fans of EA SPORTS’ NHL franchise an exclusive first opportunity to play one of the most anticipated video games of 2013,” said Brad LaDouceur, Vice President, Alternative Programming, Cineplex Entertainment. “There’s no better way to play than live on the big screen, with the opportunity to win great prizes.” As part of the grand prize, the tournament winner will have the opportunity to face-off against one of the players from the Toronto Maple Leafs, for ultimate bragging rights. The tournament will be played on the PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system, and is open to approximately 200 participants. For more information or to register, visit Cineplex.com/NHL14Tournament.com or the Cineplex Cinemas Yonge-Dundas box office. Tournament Participation tickets cost just $10.00. Spectator tickets will be available at no charge at the theatre box office, beginning at 1:00 p.m. -

Cineplex Entertainment to Offer Game of Thrones® the IMAX Experience® Tickets for This Cinema Event on Sale Now

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Cineplex Entertainment to offer Game of Thrones® The IMAX Experience® Tickets for this cinema event on sale now Toronto, ON, January 27, 2015 (TSX: CGX) –Cineplex Entertainment today announced that participating theaters will screen the epic HBO® hit Game of Thrones in IMAX. Through a partnership with HBO and IMAX, Game of Thrones will become the first television series to be shown in this immersive cinematic experience. Guests will have the opportunity to see episodes nine and ten from season four, followed by the worldwide debut of the season five sneak-peek preview. The one-week Game of Thrones engagement will begin on Thursday, January 29 at 10 p.m. and extend through February 5. Episode Synopses Episode nine, “The Watchers on the Wall,” takes place entirely at The Wall with the Night’s Watch hopelessly outnumbered as they attempt to defend Castle Black from the Wildings and features one the fiercest and most intense battle scenes ever filmed for television. Episode 10, the season finale entitled “The Children,” features Dany coming to grips with the realities of ruling a kingdom, Bran learning the startling reality of his destiny and Tyrion facing the truth of his unfortunate situation. Game of Thrones is an epic series whose storylines of treachery and nobility, family and honor, ambition and love, and death and survival, have captured the imagination of fans globally and made it one of the most popular shows on television. The IMAX release of Game of Thrones will be digitally re-mastered into the image and sound quality of The IMAX Experience®, with proprietary IMAX DMR® (Digital Re-mastering) technology. -

Signature Redacted

Perspectives on Film Distribution in the U.S.: Present and Future By Loubna Berrada Master in Management HEC Paris, 2016 SUBMITTED TO THE MIT SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MANAGEMENT STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2016 OFTECHNOLOGY 2016 Loubna Berrada. All rights reserved. JUN 08 201 The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic LIBRARIES copies of this thesis document in whole or in part ARCHIVES in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: Signature redE cted MIT Sloan School of Management May 6, 2016 Certified by: Signature redacted Juanjuan Zhang Epoch Foundation Professor of International Management Professor of Marketing MIT Sloan School of Management Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Signature redacted Rodrigo S. Verdi Associate Professor of Accounting Program Director, M.S. in Management Studies Program MIT Sloan School of Management 2 Perspectives on Film Distribution in the U.S.: Present and Future By Loubna Berrada Submitted to MIT Sloan School of Management on May 6, 2016 in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Management Studies. Abstract I believe film has the power to transform people's lives and minds and to enlighten today's generation like any other medium. This is why I wanted to write my thesis about film distribution as it will determine the future of the industry itself. The way films are distributed, accessed and consumed will be critical in shaping our future entertainment culture and the way we approach content. -

Our Creed Is What We Believe. It May Seem Like We’Ve Been Fighting This We See Leading Researchers, from All Over the Fight Forever

Our Creed is what We Believe. It May Seem Like We’ve Been Fighting This We see leading researchers, from all over the Fight Forever. But We Haven’t. world, leave their homes to come here. Because this is where they believe the fight will be There was a time, not long ago, when cancer finished. In our lifetime. was a death sentence. And the treatment was dreaded almost as much as the disease. Yes, we are still losing people to cancer. But We’ve seen that change in our lifetime, at more and more, we are controlling the cancer, The Princess Margaret. instead of the cancer controlling us. We now know that every cancer is as individual as the We’ve seen the entire process of cancer patient. So we’re developing personalized care care forever altered. We’ve seen radical that delivers the right treatment to the right mastectomies become lumpectomies. We’ve patient at the right time. We are pioneering seen the precision of image guided therapies new, innovative treatment options, like using spare more healthy tissue. We’ve seen a patient’s own immune system to fight cancer. undreamed-of advances at the cellular level and This is the future of cancer medicine, and we revolutionary work in healing beyond the body. are on the forefront of that progress, today. All in our lifetime. It may seem like we’ll be fighting this fight All at The Princess Margaret. forever. But we won’t. Because we’re closing in. We have the momentum. We have the talent.