Raging Bull” Case Finally Bring Some Consistency to the Doctrine of Laches in Copyright Infringement Cases?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wo Bleibt Blofeld?

Arnold F. Rusch AJP/PJA 11/2015 Wo bleibt Blofeld? 1622 James Bond hat Ian Fleming geschrie- ken Largo spielte jetzt aber Klaus ben. Es ging um sieben Novellen. Für Maria Brandauer, während Kim Ba- deren filmische Umsetzung nahm Fle- singer die Schurkendame Domino ming die Hilfe von Kevin McClory verkörperte, die sich später in Bond und Jack Whittingham in Anspruch. verknallt und zu ihm überläuft. Wei- Zu dritt verfassten sie das Drehbuch tere McClory-Konkurrenzfilme – jetzt für Thunderball. 1961 veröffentlichte unter dem Label von Sony – konnte Fleming dennoch alleine eine Novelle Danjaq in der Folge mit einer Flut von mit dem gleichen Titel – Whittingham Prozessen verhindern. und McClory klagten sofort in Lon- Der amerikanische Prozess vor don.1 dem Appellationsgericht des Ninth Danjaq bereitete sich im gleichen Circuit im Jahre 2001 setzte dem epi- Zeitpunkt darauf vor, James Bond- schen Streit ein vorläufiges Ende. Die Filme zu produzieren. Sie erwarben Richter hielten fest, dass McClory die Rechte von Fleming alleine und seine Rechte durch laches, d.h. lang- 3 ARNOLD F. RUSCH gaben ein eigenes Drehbuch zu Thun- jährige Untätigkeit, verwirkt habe. Prof. Dr. iur., Rechtsanwalt, LL.M., Zürich derball in Auftrag. Wegen des Streits Die endgültige Einigung erzielten die um die Rechte an der Thunderball- Streithähne erst mit der Einigung im Geschichte drehten sie zuerst Dr. No, Jahre 2013, die Danjaq die umfassen- der 1962 in den Kinos erschien. In den Rechte an James Bond gewährte, James Bond und SPECTRE sind zu- der Zwischenzeit knickte Fleming im mitsamt allen Schurken und Schur- rück, aber was ist mit Blofeld? ursprünglichen Prozess um Thunder- kenvereinigungen. -

Paramount Consent Decree Review Public Comments 2018

COMMENTS OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF THEATRE OWNERS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, ANTITRUST DIVISION REVIEW OF PARAMOUNT CONSENT DECREES October 1, 2018 National Association of Theatre Owners 1705 N Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 (202) 962-0054 I. INTRODUCTION The National Association of Theatre Owners (“NATO”) respectfully submits the following comments in response to the U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust Division’s (the “Department”) announced intentions to review the Paramount Consent Decrees (the “Decrees”). Individual motion picture theater companies may comment on the five various provisions of the Decrees but NATO’s comment will focus on one seminal provision of the Decrees. Specifically, NATO urges the Department to maintain the prohibition on block booking, as that prohibition undoubtedly continues to support pro-competitive practices. NATO is the largest motion picture exhibition trade organization in the world, representing more than 33,000 movie screens in all 50 states, and additional cinemas in 96 countries worldwide. Our membership includes the largest cinema chains in the world and hundreds of independent theater owners. NATO and its members have a significant interest in preserving an open marketplace in the North American film industry. North America remains the biggest film-going market in the world: It accounts for roughly 30% of global revenue from only 5% of the global population. The strength of the American movie industry depends on the availability of a wide assortment of films catering to the varied tastes of moviegoers. Indeed, both global blockbusters and low- budget independent fare are necessary to the financial vitality and reputation of the American film industry. -

The 007Th Minute Ebook Edition

“What a load of crap. Next time, mate, keep your drug tripping private.” JACQUES A person on Facebook. STEWART “What utter drivel” Another person on Facebook. “I may be in the minority here, but I find these editorial pieces to be completely unreadable garbage.” Guess where that one came from. “No, you’re not. Honestly, I think of this the same Bond thinks of his obituary by M.” Chap above’s made a chum. This might be what Facebook is for. That’s rather lovely. Isn’t the internet super? “I don’t get it either and I don’t have the guts to say it because I fear their rhetoric or they’d might just ignore me. After reading one of these I feel like I’ve walked in on a Specter round table meeting of which I do not belong. I suppose I’m less a Bond fan because I haven’t read all the novels. I just figured these were for the fans who’ve read all the novels including the continuation ones, fan’s of literary Bond instead of the films. They leave me wondering if I can even read or if I even have a grasp of the language itself.” No comment. This ebook is not for sale but only available as a free download at Commanderbond.net. If you downloaded this ebook and want to give something in return, please make a donation to UNICEF, or any other cause of your personal choice. BOOK Trespassers will be masticated. Fnarr. BOOK a commanderbond.net ebook COMMANDERBOND.NET BROUGHT TO YOU BY COMMANDERBOND.NET a commanderbond.net book Jacques I. -

Boek Het James Bond

HET JAMES RAY ROMBOUT BOND BOEK VAN DR NO TOT NO TIME TO DIE WAARBORG TEGEN CHAOS? Waarom is James Bond zo succesvol? Wat zijn de mechanismen van het succes? Dat zijn vaak de eerste vragen die journalisten me stellen. Het kan gewoon niet anders dan dat de figuur James Bond op een ijzersterke structuur is geschraagd. Er is de literaire laag, dankzij Ian Fleming, maar er is ook het filmisch raamwerk. Je vindt verder in dit boek hoe een en ander in elkaar steekt. 003 James Bond is meer dan de som van alle boeken en films. De Bondwereld is een vloeibare kracht die al tegen vijf generaties aanklotst. Dit boek wil dit ondubbelzinnig aantonen. Een ultiem naslagboek, niet opgevat als encyclopedie, maar als een gezaghebbende opinie, niet noodzakelijk een kopie van wat EON ons voorhoudt. En de boeken dan? Ik zou ze maar niet vergeten. Ian Fleming verdient een monument voor zijn creatie, die de wereld van boek en film verbaasde en domineerde. Niet alleen als fictieve held, maar vooral als metafoor voor het wereldwijde geloof in de stijd tegen het kwaad. Zowat alle actiefilms van de jaren ’70, ’80 en ’90 zijn schatplichtig aan de Grote Roerganger. Niet alleen qua thema en uitwerking, vrouwen en stunts, snufjes en locaties, maar dankzij niet aflatend marketingonderzoek heeft de filmindustrie begrippen mogen ontdekken zoals teaser, product- placement of tie-ins. Het beste van Bond blijft Bond zelf. Hij is de sluitsteen van twee werelden. Het idool voor miljoenen mensen die zich al meer dan vijftig jaar een stukje James Bond wanen in hun dagelijks bestaan. -

Entertainment Studios Networks the Goodfriend Group 1925 Century Park East, 10Th Floor 208 I St

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of Conditions Imposed in the ) WC Docket No.16-197 Charter Communications-Time Warner ) Cable-Bright House Networks Order ) PETITION TO DENY Mark DeVitre David R. Goodfriend Executive Vice President and General Counsel Meagan M. Sunn Entertainment Studios Networks The Goodfriend Group 1925 Century Park East, 10th Floor 208 I St. NE Los Angeles, CA 90067 Washington, D.C. 20002 (310) 277-3500 (202) 549-5612 July 22, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY…………………………………………....1 II. CHARTER’S INCENTIVE AND ABILITY TO FAVOR SOME EDGE PROVIDERS OVER OTHERS AND ITS SELF-PROFESSED DESIRE TO DISCRIMINATE BASED ON RACE SHOULD PREVENT THE COMMISSION FROM LIFTING MERGER CONDITIONS…............................3 A. The Commission established the merger conditions to prevent Charter from engaging in anti-competitive economic discrimination…...............3 B. Charter’s statements in federal district and appellate court reveal its desire to discriminate based on race….....................................................4 C. Lifting the merger conditions likely would harm ESN, other minority-owned businesses, and minority consumers…..........................5 III. THE COMMISSION’S UNTIMELY COMMENCEMENT OF THIS PROCEEDING SHOULD RENDER THE OUTCOME MOOT………………..11 A. The Commission lacks authority to commence this proceeding prior to August 18, 2020….....................................................................................11 B. ESN relied on the timeframe -

The US Film Industry

Jono Polansky, Onbeyond LLC August 2020 _____________________________________________________________________________________________ This SFM guide to who owns what in the US screen entertainment industry — movies, broadcast, cable and streaming — has been updated to reflect developments in tobacco content and changes in corporate ownership. We put this map together so public health experts, parents, young people and policy makers can identify who decides if smoking shows up in entertainment accessible to kids. The US film industry MAJOR STUDIOS | The US feature film industry is dominated by five “major studio” distributors. In 2019, their top-grossing films accounted for 81 percent of all youth-rated tobacco impressions delivered to domestic theater audiences. The studios develop, finance, and market film projects domestically and worldwide. Almost all films with production budgets greater than $50 million are major studio films. Studios may not break even on theatrical showings of a film, but a film’s box office, split roughly 50-50 with the theaters, strongly predicts the revenue the studio keeps to itself when the film is later released on DVD and licensed to on-demand, cable, and broadcast services. Most studio revenue comes from those “long tail” after-markets. In addition, 70 percent of US studios’ theatrical revenue now comes from outside the United States, which helps explain why easy-to-sell “franchise” films are prized by major studios. The major studios are represented by a trade group, the Motion Picture Association (MPA), dominate its board of directors. The MPA owns and administers the movie ratings (G/PG/PG-13/R,NC-17), with a nod to the National Association of Theatre Owners (NATO), which plays a role in enforcing age restrictions. -

Das Es Sich Bei Die Another Day Um Einen James Bond-Film Handelt, Erkennt Man Schon Am Titel

Ein Bond ist nicht genug Zum 20. mal kehrte James Bond mit Die Another Day im November in die Kinos zurück. Seinen ersten Leinwand-Auftritt hatte der britische Nobelagent vor 40 Jahren. Anlass genug, um auf die Ursprünge des erfolgreichsten Filmfranchises der Kinogeschichte zurückzublicken. ROBERT BLANCHET Dass es sich bei Die Another Day um den neuesten James-Bond-Film handelt, erkennt man schon am Titel: Leben und Tod, Luxus, Eros und Unendlichkeit - mindestens eines dieser Elemente kommt in fast allen Bondfilmtiteln vor. Gut gewählt ist er aber auch deshalb, weil er perfekt zum Jubiläum passt, das das älteste Filmfranchise des Gegenwartskinos vor kurzem feierte: Seit 40 Jahren steht 007 im Geheimdienst Ihrer Majestät; 50 Jahre wenn man die Bücher mit dazurechnet – und tatsächlich ist die Zeit für den Agenten mit der Lizenz zum Töten wohl noch lange nicht gekommen. Seit Pierce Brosnan 1995 die Walther PPK von Timothy Dalton übernommen hat, spielen Bondsequels wieder fast doppelt so viel ein wie in den für das Spion-Genre eher mageren Achtzigerjahren. Mit Blockbusterserien wie Mission: Impossible (Paramount), XXX (Columbia TriStar), und Austin Powers (Warner Bros./New Line) hat mittlerweile fast jedes der Hollywoodstudios sein eigenes Bondderivat im Programm. Und wenn Madonna nach Austin Powers dieses Jahr endlich auch den echten Bond mit einem Titelsong beehrt, ist dies nur konsequent, wenn man bedenkt, wie viel die zeitgenössische Popkultur dem Retrochic der 20 offiziellen Bondfilme und ihren Soundtracks schuldet. Begonnen hat alles 1952 in Goldeneye, dem jamaikanischen Winterrefugium von Ian Flemming. Umgeben von Palmen, illustren Gästen und dem zunehmend frostigeren politischen Klima des Kalten Krieges schuf der Journalist und Bonvivant hier eine Romanfigur, die wohl vieles von dem verkörperte, was er sich für sein eigenes Leben erträumte. -

George Lazenby -- Trivia

George Lazenby -- Trivia Was the highest paid male model in Europe prior to playing James Bond. Except for TV commercials, he had no previous acting experience when he was cast as James Bond. Bond producer Albert R. Broccoli, remarked that Lazenby could have been the best Bond had he not quit after just one film. He was a martial arts instructor in the Australian army, and holds more than one black belt in the martial arts. He studied martial arts under Bruce Lee himself. He was set to co-star in the biggest budgeted action/martial arts film of all time in 1973, along with Bruce Lee. However, Lee died two weeks before the film was to begin shooting. (The film, originally titled "Shrine of Ultimate Bliss," was eventually made, but on a considerably smaller budget, and was given a limited theatrical release, excluding the U.S.) Broke a stuntman's nose during a Bond fight screen test, and it was this physical strength that finalized his selection as Bond. Was considered by producer Kevin McClory to play James Bond 007 in Never Say Never Again (1983) but was dropped from consideration when Sean Connery confirmed he wanted the role. He was offered a seven-movie deal by the Bond producers, but quit the role because he felt that the tuxedo-clad Bond would die out in the new hippie culture that had permeated society in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Was the #1 male fashion model in the world from 1964 to 1968. His agent, Maggie Smith, told him that he should apply for Bond, since in her opinion, his arrogance would surely win him the role. -

Emmy Nominations

2021 Emmy® Awards 73rd Emmy Awards Complete Nominations List Outstanding Animated Program Big Mouth • The New Me • Netflix • Netflix Bob's Burgers • Worms Of In-Rear-Ment • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television / Bento Box Animation Genndy Tartakovsky's Primal • Plague Of Madness • Adult Swim • Cartoon Network Studios The Simpsons • The Dad-Feelings Limited • FOX • A Gracie Films Production in association with 20th Television Animation South Park: The Pandemic Special • Comedy Central • Central Productions, LLC Outstanding Short Form Animated Program Love, Death + Robots • Ice • Netflix • Blur Studio for Netflix Maggie Simpson In: The Force Awakens From Its Nap • Disney+ • A Gracie Films Production in association with 20th Television Animation Once Upon A Snowman • Disney+ • Walt Disney Animation Studios Robot Chicken • Endgame • Adult Swim • A Stoopid Buddy Stoodios production with Williams Street and Sony Pictures Television Outstanding Production Design For A Narrative Contemporary Program (One Hour Or More) The Flight Attendant • After Dark • HBO Max • HBO Max in association with Berlanti Productions, Yes, Norman Productions, and Warner Bros. Television Sara K. White, Production Designer Christine Foley, Art Director Jessica Petruccelli, Set Decorator The Handmaid's Tale • Chicago • Hulu • Hulu, MGM, Daniel Wilson Productions, The Littlefield Company, White Oak Pictures Elisabeth Williams, Production Designer Martha Sparrow, Art Director Larry Spittle, Art Director Rob Hepburn, Set Decorator Mare Of Easttown • HBO • HBO in association with wiip Studios, TPhaeg eL o1w Dweller Productions, Juggle Productions, Mayhem Mare Of Easttown • HBO • HBO in association with wiip Studios, The Low Dweller Productions, Juggle Productions, Mayhem and Zobot Projects Keith P. Cunningham, Production Designer James F. Truesdale, Art Director Edward McLoughlin, Set Decorator The Undoing • HBO • HBO in association with Made Up Stories, Blossom Films, David E. -

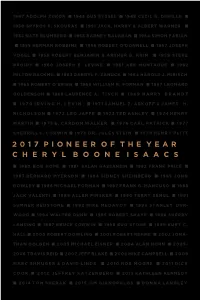

2017 Pioneer of the Year C H E R Y L B O O N E I S a A

1947 ADOLPH ZUKOR n 1948 GUS EYSSEL n 1949 CECIL B. DEMILLE n 1950 SPYROS P. SKOURAS n 1951 JACK, HARRY & ALBERT WARNER n 1952 NATE BLUMBERG n 1953 BARNEY BALABAN n 1954 SIMON FABIAN n 1955 HERMAN ROBBINS n 1956 ROBERT O’DONNELL n 1957 JOSEPH VOGEL n 1958 ROBERT BENJAMIN & ARTHUR B. KRIM n 1959 STEVE BROIDY n 1960 JOSEPH E. LEVINE n 1961 ABE MONTAGUE n 1962 MILTON RACKMIL n 1963 DARRYL F. ZANUCK n 1964 HAROLD J. MIRISCH n 1965 ROBERT O’BRIEN n 1966 WILLIAM R. FORMAN n 1967 LEONARD GOLDENSON n 1968 LAURENCE A. TISCH n 1969 HARRY BRANDT n 1970 IRVING H. LEVIN n 1971 SAMUEL Z. ARKOFF & JAMES H . NICHOLSON n 1972 LEO JAFFE n 1973 TED ASHLEY n 1974 HENRY MARTIN n 1975 E. CARDON WALKER n 1976 CARL PATRICK n 1977 SHERRILL C. CORWIN n 1978 DR. JULES STEIN n 1979 HENRY PLITT 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS n 1980 BOB HOPE n 1981 SALAH HASSANEIN n 1982 FRANK PRICE n 1983 BERNARD MYERSON n 1984 SIDNEY SHEINBERG n 1985 JOHN ROWLEY n 1986 MICHAEL FORMAN n 1987 FRANK G. MANCUSO n 1988 JACK VALENTI n 1989 ALLEN PINSKER n 1990 TERRY SEMEL n 1991 SUMNER REDSTONE n 1992 MIKE MEDAVOY n 1993 STANLEY DUR- WOOD n 1994 WALTER DUNN n 1995 ROBERT SHAYE n 1996 SHERRY LANSING n 1997 BRUCE CORWIN n 1998 BUD STONE n 1999 KURT C. HALL n 2000 ROBERT DOWLING n 2001 ROBERT REHME n 2002 JONA- THAN DOLGEN n 2003 MICHAEL EISNER n 2004 ALAN HORN n 2005– 2006 TRAVIS REID n 2007 JEFF BLAKE n 2008 MIKE CAMPBELL n 2009 MARC SHMUGER & DAVID LINDE n 2010 ROB MOORE n 2011 DICK COOK n 2012 JEFFREY KATZENBERG n 2013 KATHLEEN KENNEDY n 2014 TOM SHERAK n 2015 JIM GIANOPULOS n DONNA LANGLEY 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR Welcome On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Will Rogers Motion Picture Pioneers Foundation, thank you for attending the 2017 Pioneer of the Year Dinner. -

The Political Economy of Independent Film: a Case Study of Kevin Smith Films

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 The Political Economy of Independent Films: A Case Study of Kevin Smith Films Grace Kathleen Keenan Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF INDEPENDENT FILMS: A CASE STUDY OF KEVIN SMITH FILMS By GRACE KATHLEEN KEENAN A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Media Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Grace Kathleen Keenan defended on April 9, 2009. ____________________________________ Jennifer M. Proffitt Professor Directing Thesis ____________________________________ Stephen D. McDowell Committee Member ____________________________________ Andrew Opel Committee Member __________________________________________________ Stephen D. McDowell, Chair, Department of Communication __________________________________________________ Gary R. Heald, Interim Dean, College of Communication The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii For my parents, who have always seen me as their shining star iii ACKNOWLEGEMENTS Dr. Proffitt: Without your dedication to learning and students, this thesis would have been impossible. You truly have the patience of an angel. Much love. Dad: How do you put up with me? Thank you for all your emotional and financial support. Mom: You are always striving to understand. I think I get that from you. Newton Hazelbaker: Again, how do you put up with me? Thank you for your absolute and unconditional love. Laura Clements: Perhaps the most fun person I’ve ever met. -

Copyright in Teams Anthony J

Copyright in Teams Anthony J. Caseyt & Andres Sawickitt Dozens of people worked together to produce Casablanca. But a single person working alone wrote The Sound and the Fury. While almost all films are produced by large collaborations,no great novel ever resulted from the work of a team. Why does the frequency and success of collaborative creative production vary across art forms? The answer lies in significantpart at the intersection of intellectualproperty law and the theory of the firm. Existing analyses in this area often focus on patent law and look almost exclusively to a property-rights theory of the firm. The impli- cations of organizational theory for collaborative creativity and its intersection with copyright law have been less examined. To fill this gap, we look to team- production and moral-hazardtheories to understandhow copyright law can facili- tate or impede collaborative creative production. While existing legal theories look only at how creative goods are integrated with complementary assets, we explore how the creative goods themselves are produced. This analysis sheds new light on poorly understood features of copyright law, including the derivative-works right, the ownership structure ofa joint work, and the work-made-for-hire doctrine. INTRODUCTION ....................................................... 1684 I. A THEORY OF CREATIVE PRODUCTION ........................... 1690 A. The Limitations of Property-Rights Theory ..................... 1690 B. Theories of Team Production. .................... .......... 1694 1. The monitoring manager ........................ 1695 t Assistant Professor of Law, The University of Chicago Law School. The Jerome F. Kutak Faculty Fund provided research support. ft Associate Professor of Law, University of Miami School of Law. This article is built largely on foundational theories pioneered by the late Ronald H.