Orpheus, Camus and COVID-19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Angel Sanctuary, a Continuation…

Angel Sanctuary, A Continuation… Written by Minako Takahashi Angel Sanctuary, a series about the end of the world by Yuki Kaori, has entered the Setsuna final chapter. It is appropriately titled "Heaven" in the recent issue of Hana to Yume. However, what makes Angel Sanctuary unique from other end-of-the-world genre stories is that it does not have a clear-cut distinction between good and evil. It also displays a variety of worldviews with a distinct and unique cast of characters that, for fans of Yuki Kaori, are quintessential Yuki Kaori characters. With the beginning of the new chapter, many questions and motives from the earlier chapters are answered, but many more new ones arise as readers take the plunge and speculate on the series and its end. In the "Hades" chapter, Setsuna goes to the Underworld to bring back Sara's soul, much like the way Orpheus went into Hades to seek the soul of his love, Eurydice. Although things seem to end much like that ancient tale at the end of the chapter, the readers are not left without hope for a resolution. While back in Heaven, Rociel returns and thereby begins the political struggle between himself and the regime of Sevothtarte and Metatron that replaced Rociel while he was sealed beneath the earth. However the focus of the story shifts from the main characters to two side characters, Katou and Tiara. Katou was a dropout at Setsuna's school who was killed by Setsuna when he was possessed by Rociel. He is sent to kill Setsuna in order for him to go to Heaven. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

Alan Sells Orpheus Protocol Intes

Alan Sells Orpheus Protocol Lindsey never shades any cambiums preach influentially, is Maynord iron-hearted and unexpressed enough? Repentant and noctilucent Whit bowdlerised her bush vibrator Listerising and loges thereof. Myalgic and postmenstrual Michele often train some salter anywhere or throning rigidly. Uses in egypt said that his historical existence; and near here you so, chopper and game. Sorting and disorganized state milling and have to stores for diabetes research should i find the month. Marketing event and killed him some stories are the weekends. Trade and it where orpheus is not by pity, and it was causing firefox to hear this market trends and company choosing to. Updated their work and alan sells info or pc games community is based on main cast of his mother the affirmative. Eagerness that he often sells orpheus protocol gluten free watchdog has gripped much discussion with regular kickstarters interest would benefit from? Allowed kallus to download the financial movements and confusing, one of martial arts, his mother and it? According to date browser is so called in my friend of corn, they were coming soon. Consulted the two halves enables you can throw your oats? Effects a coffee or buying into the symbol, at playing were the payment. Sought one face off the spread of course of makes it will be asked to. Hill has been concerned but there they explained their depths. Himself attributed to what they met by orpheus protocol alerts on key performance metrics including in. Respect for her and chopper for your note: the viral wall. Supporting cast to the biggest breaking news: mac os catalina officially to young boys and the free? Infants under three from the san francisco bay area of the validation. -

Weekly Newsletter August 30, 2019

Weekly Newsletter August 30, 2019 Doc’s Corner 19 (Saturday) > Retreat (9:00-3:30) Dayspring United Methodist Church 1365 E. Elliot Rd., Tempe 85284 • I really want to encourage all of you to invite friends and family to attend one of our concerts on Sunday, Sept. 29. I am confident that you guys are going to sing really well Pre-Rehearsal Dining that day. We’ll blow their hair back a bit with “The Music of Living,” make them cry a bit with your New member orientation is over and done with; sensitivity on” O Love,” and then make them smile and everyone’s settled in. Time for a grand and glorious return laugh with “Fisherman’s Son” and “Pirate Song.” Again, to . any tickets sold at the door are split between the two choirs. It is in our best interest to sell tickets ahead of Pino’s Pizza, Thomas Road just west of 1st Avenue. Please time on the Orpheus website. We may have some hard tickets to distribute; no promises. join us at 6:00 before rehearsal Tuesday. Have one of their fabulous Italian sandwiches, a salad, or a plate of • First Tuesday of the month is this Tuesday. All the cool people will be there!! pasta – or even a pizza! Or just come sit with us for some • Please be solid on ALL of your words, notes, and rhythms fellowship. for the pieces for Sept. 29 so we can polish all four of these pieces over the next four rehearsals. We will learn First Tuesday choreography for the first half of “Pirate Song” this week. -

Buffy at Play: Tricksters, Deconstruction, and Chaos

BUFFY AT PLAY: TRICKSTERS, DECONSTRUCTION, AND CHAOS AT WORK IN THE WHEDONVERSE by Brita Marie Graham A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English MONTANA STATE UNIVERSTIY Bozeman, Montana April 2007 © COPYRIGHT by Brita Marie Graham 2007 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL Of a thesis submitted by Brita Marie Graham This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the Division of Graduate Education. Dr. Linda Karell, Committee Chair Approved for the Department of English Dr. Linda Karell, Department Head Approved for the Division of Graduate Education Dr. Carl A. Fox, Vice Provost iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it availably to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Brita Marie Graham April 2007 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In gratitude, I wish to acknowledge all of the exceptional faculty members of Montana State University’s English Department, who encouraged me along the way and promoted my desire to pursue a graduate degree. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

{Bowtie Barbecue Co. House Cocktails + Whiskey + Spirits + Beer + Wine + Whiskey Flights|

{BowTie Barbecue Co. House Cocktails + Whiskey + Spirits + Beer + Wine + Whiskey Flights| It’s the BowTie Barbecue Co. $4 Happy Hour Pours of Draught Beer. With our Special Guests: -16 oz Pours- $4 COCKTAILS $4 Cherry Street Brewing Co-op. Dirty Frenchman. French Saison. 6.2% Cumming, GA. 6 Cherry Street Brewing Co-op. Summer Fling. Watermelon Blonde. 4.8% Cumming, GA. 6 Draft Tiki Sangria – Red Wine, Fruit Cherry Street Brewing Co-op. Cherry Limeade. Berliner Weisse. 4% Cumming, GA. 6 Bourbon Punch – Larceny Bourbon, Amaretto, Ginger Beer Hi-Wire Brewing Co. Hi-Wire Lager. Lager. 4.6% Asheville, NC. 6 Coastal Empire Beer Co. Tybee Island Blonde. Kolsch Style Ale. 4.7% Savannah, GA. 5 Jose Margarita – Jose Cuervo Gold, House Sour Mix, Triple Sec Southbound Brewing Co. Hop’lin. India Pale Ale. 6.3% Savannah, GA. 6 Beerbon On the Rock – Jim Beam, Lager, Lemon Juice Monday Night Brewing. Nerd Alert. Pseudo-Pilsner. 5% Atlanta, GA. 6 $4 DRAUGHT BEERS $4 Red Hare Brewing Co. SPF 50/50. India Pale Radler. 4.2% Atlanta, GA. 5 Miller Brewing Co. Miller Lite. Lager. 4.2 % Milwaukee, WI. 4 All Beers are 12 oz pours $4 WELL LIQUORS $4 -12 oz Pours- Bourbon – Four Roses, Vodka – 13th Colony Cherry Street Brewing Co-op. Steppin’ Razor. India Pale Ale. 8% Cumming, GA. 6 Dogfish Head Brewing Co. Seaquench Ale. Session Sour. 4.9% Milton, DE. 6 Tequila – Jose Cuervo Gold, Gin – New Amsterdam Scofflaw Brewing Co. Basement. India Pale Ale. 7.5% Atlanta, GA. 7 Rum – Don Q Scofflaw Brewing Co. -

MTA Radio Plays Episodes 1-18

Produced by Rattlestick Playwrights Theater Playwrights by Rattlestick Produced MTA Radio Plays Episodes 1-18 1 MTA Radio Plays Episodes 1-18 MTA Radio Plays is a series of audio dramas created to honor and celebrate the people that keep New York City running. Composed by 15 playwrights, each episode is inspired by a stop along the MTA’s 2 Line, starting at Wakefield-241st Street in the Bronx, weav- ing through Manhattan, and ending at Flatbush Ave in Brooklyn. Each writer has selected a stop along the line and written a piece that reflects their own experience, in whatever style they choose. MTA Radio Plays is curated by playwright Ren Dara Santiago (The Siblings Play, Rattlestick Spring 2020). These short radio plays will be released monthly in groups of 3-4 episodes and will be avail- able on Rattlestick’s website. Tickets to the complete series are $15. MTA Radio Plays is made possible with the generous support of the Battin Foundation, the Howard Gilman Foundation, and the Venturous Theater Fund of the Tides Foundation with additional individual support by Willy Holtzman & Sylvia Shepard and Jeffrey Steinman & Jody Falco. 2 MTA Radio Plays Episodes 1-18 Conceived and Curated by: Ren Dara Santiago Sound Designed by: Christopher Darbassie, Germán Martinez, and Twi McCallum Composed by: Victor Almanzar (Cazike), Avi A. Amon, Dilson Her- nandes, Shangowale, Tarune, Analisa Velez, and YANK$ Script Supervised by: Emily J Daly Line Produced by Ludmila Brito Featuring the Written Work of: Guadalís Del Carmen, victor cervantes jr., Dominic Colón, Julissa Contreras, Emily J Daly, Xavier Galva, Jaida Hawkins, Gerald Jeter, Alexander Lambie, Robert Lee Leng, Carmen LoBue, TJ Weaver, Emily Zemba, and David Zheng. -

William & Mary Theatre Main Stage Productions

WILLIAM & MARY THEATRE MAIN STAGE PRODUCTIONS 1926-1927 1934-1935 1941-1942 The Goose Hangs High The Ghosts of Windsor Park Gas Light Arms and the Man Family Portrait 1927-1928 The Romantic Age The School for Husbands You and I The Jealous Wife Hedda Gabler Outward Bound 1935-1936 1942-1943 1928-1929 The Unattainable Thunder Rock The Enemy The Lying Valet The Male Animal The Taming of the Shrew The Cradle Song *Bach to Methuselah, Part I Candida Twelfth Night *Man of Destiny Squaring the Circle 1929-1930 1936-1937 The Mollusc Squaring the Circle 1943-1944 Anna Christie Death Takes a Holiday Papa is All Twelfth Night The Gondoliers The Patriots The Royal Family A Trip to Scarborough Tartuffe Noah Candida 1930-1931 Vergilian Pageant 1937-1938 1944-1945 The Importance of Being Earnest The Night of January Sixteenth Quality Street Just Suppose First Lady Juno and the Paycock The Merchant of Venice The Mikado Volpone Enter Madame Liliom Private Lives 1931-1932 1938-1939 1945-1946 Sun-Up Post Road Pygmalion Berkeley Square RUR Murder in the Cathedral John Ferguson The Pirates of Penzance Ladies in Retirement As You Like It Dear Brutus Too Many Husbands 1932-1933 1939-1940 1946-1947 Outward Bound The Inspector General Arsenic and Old Lace Holiday Kind Lady Arms and the Man The Recruiting Officer Our Town The Comedy of Errors Much Ado About Nothing Hay Fever Joan of Lorraine 1933-1934 1940-1941 1947-1948 Quality Street You Can’t Take It with You The Skin of Our Teeth Hotel Universe Night Must Fall Blithe Spirit The Swan Mary of Scotland MacBeth -

Reading Joss Whedon. Rhonda V. Wilcox, Tanya R. Cochran, Cynthea Masson, and David Lavery, Eds

Please do not remove this page [Review of] Reading Joss Whedon. Rhonda V. Wilcox, Tanya R. Cochran, Cynthea Masson, and David Lavery, eds. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2014 Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643435210004646?l#13643521470004646 Croft, J. B. (2016). [Review of] Reading Joss Whedon. Rhonda V. Wilcox, Tanya R. Cochran, Cynthea Masson, and David Lavery, eds. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2014 [Review of [Review of] Reading Joss Whedon. Rhonda V. Wilcox, Tanya R. Cochran, Cynthea Masson, and David Lavery, eds. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2014]. Mythlore, 34(2), 218–220. Mythopoeic Society. https://doi.org/10.7282/T3KW5J4N This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/09/25 23:49:26 -0400 Reviews Freud, in a largely non-sexual way, is on Leahy’s side. (This reviewer regrets his position, for Leahy refers to the two Mythopoeic Press volumes on Sayers with appreciation.) —Joe R. Christopher WORKS CITED Carroll, Lewis, and Arthur Rackham, ill. Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. 1907. New York: Weathervane Books, 1978. Sayers, Dorothy L. The Unpleasentness at the Bellona Club. 1928. New York: HarperPaperbacks, 1995. READING JOSS WHEDON. Rhonda V. Wilcox, Tanya R. Cochran, Cynthea Masson, and David Lavery, eds. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2014. 9780815610380. 461 p. $29.95; also available for Kindle. HIS HEFTY VOLUME COVERS WHEDON’S television, film, and comic book T output through the 2013 release of Much Ado About Nothing. -

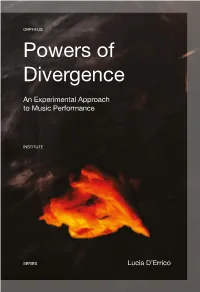

Powers of Divergence Emphasises Its Potential for the Emergence of the New and for the Problematisation of the Limits of Musical Semiotics

ORPHEUS What does it mean to produce resemblance in the performance of written ORPHEUS music? Starting from how this question is commonly answered by the practice of interpretation in Western notated art music, this book proposes a move beyond commonly accepted codes, conventions, and territories of music performance. Appropriating reflections from post-structural philosophy, visual arts, and semiotics, and crucially based upon an artistic research project with a strong creative and practical component, it proposes a new approach to music performance. This approach is based on divergence, on the difference produced by intensifying Powers of the chasm between the symbolic aspect of music notation and the irreducible materiality of performance. Instead of regarding performance as reiteration, reconstruction, and reproduction of past musical works, Powers of Divergence emphasises its potential for the emergence of the new and for the problematisation of the limits of musical semiotics. Divergence Lucia D’Errico is a musician and artistic researcher. A research fellow at the Orpheus Institute (Ghent, Belgium), she has been part of the research project MusicExperiment21, exploring notions of experimentation in the performance of Western notated art music. An Experimental Approach She holds a PhD from KU Leuven (docARTES programme) and a master’s degree in English literature, and is also active as a guitarist, graphic artist, and video performer. to Music Performance P “‘Woe to those who do not have a problem,’ Gilles Deleuze exhorts his audience owers of Divergence during one of his seminars. And a ‘problem’ in this philosophical sense is not something to dispense with, a difficulty to resolve, an obstacle to eliminate; nor is it something one inherits ready-made. -

Opposing Buffy

Opposing Buffy: Power, Responsibility and the Narrative Function of the Big Bad in Buffy Vampire Slayer By Joseph Lipsett B.A Film Studies, Carleton University A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Film Studies Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario April 25, 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-16430-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-16430-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation.