Overview and Hotspots Analysis of the Tourism Value Chain in the Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ILOILO SCIENCE and TECHNOLOGY UNIVERSITY SEA-TVET EXPERIENCE ISAT University Basic Facts

ILOILO SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY UNIVERSITY SEA-TVET EXPERIENCE ISAT University Basic Facts Tourist Attractions Miagao Church Molo Church Tourist Attractions Lapaz Bachoy Biscocho Tourist Attractions Iloilo Infrastructure Iloilo Convention Center Iloilo Esplanade Iloilo Infrastructure Iloilo Dinagyang Festival ISAT University Basic Facts VISION ISAT U as a leading science and technology university in Southeast Asia by 2030. CORE VALUES Integrity Commitment Accountability Responsiveness Excellence ISAT University Basic Facts • Formerly Iloilo Trade School (ITS) founded in 1905 • Converted to Iloilo School of Arts and Trades (ISAT) in 1939 by Commonwealth Act No. 313 ISAT University Basic Facts On May 18, 1983 by virtue of Batas Pambansa Blg. 395 ISAT was converted into Western Visayas College of Science and Technology (WVCST) Republic Act 10595 4 June 2013 An Act Converting the Western Visayas College of Science and Technology (WVCST) in the City of Iloilo into a State University to be known as the ILOILO SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY UNIVERSITY May 18, 2015 Program Offerings Hotel and Restaurant Technology SEATVET Partners •Support of the Administration •Support of the National and International Affairs Coordinators •Good relationship and numerous industry partners •Very supportive and caring buddies • Financially challenging but rewarding • Forge strong alliance with partner institutions • Embrace and appreciate cultural differences • Realization of their capacity to accommodate other culture especially in the workplace • More profound and deeper appreciation and enhancement of their soft skills • Learned self-reliance and emotional independence Contact Details Dr. Raul F. Muyong SUC President Mailing Add: Burgos St., La Paz, Iloilo City, Philippines • Telephone Number: +63-33-3207190 • Fax Number: +63-33-3294274 • E-mail address: [email protected] • Website address: www.isatu.edu.ph . -

Distribution Agreement in Presenting This Thesis Or Dissertation As A

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Signature: _____________________________ ________________ Ryan Tans Date Decentralization and the Politics of Local Taxation in Southeast Asia By Ryan Tans Doctor of Philosophy Political Science _________________________________________ Richard F. Doner Advisor _________________________________________ Jennifer Gandhi Committee Member _________________________________________ Douglas Kammen Committee Member _________________________________________ Eric R. Reinhardt Committee Member Accepted: _________________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies ___________________ Date Decentralization and the Politics of Local Taxation in Southeast Asia By Ryan Tans M.A., Emory University, 2015 M.A., National University of Singapore, 2011 B.A., Calvin College, 2004 Advisor: -

Iloilo City Outreach

MESSAGE FOR U.S. CITIZENS U.S. Embassy representatives from the American Citizens Services (ACS) unit of the Consular Section; and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (USDVA) will be in: ILOILO CITY Friday, April 26, 2019 8:00am to 11:00am Richmonde Hotel Iloilo Megaworld Blvd. cor. Enterprise Road, Iloilo Business Park, Mandurriao, Iloilo City ACS will: IMPORTANT NOTICE: While fees are listed in U.S. Dollars, because of bank Accept applications for Passports and Consular Reports of Birth regulations, we can only accept Philippine pesos as payment Abroad (CRBA) for services. Peso exchange rate will be provided during the Provide information about registering with the U.S. Embassy outreach. Payment must be made in the exact amount, as no Provide notarial services and affidavits of legal capacity to change will be available. marry in the Philippines SCHEDULE OF FEES Please note: Citizenship and Passport applicants must read all Passports: information on the U.S. Embassy website and bring the Adult (16 and above) Passport Application (DS11) $145 completed checklist with them. Minor (under 16) Passport Application $115 Passports: Passport Renewal (minor DS11) $115 https://ph.usembassy.gov/u-s-citizen-services/passports/ (adult DS82) $110 CRBAs: Consular Report of Birth Abroad $100 https://ph.usembassy.gov/u-s-citizen-services/citizenship- Notarials: services/ Affidavit of Legal Capacity to Marry $50 Applicants who do not bring the required documentation and Affidavit (Subscribed and Sworn To) $50 photocopies will be turned away and must schedule an Additional Copy $50 appointment at the U.S. Embassy. Other doc. related to the same transaction $50 Due to high demand for services, ACS may not be able to Acknowledgment of Signature $50 accommodate all applicants for interview during the three Voting registration card or absentee ballot no fee hours of the outreach and may implement a limit for some Report of Death of an American Citizen no fee services. -

Annual Report 2018

ALLIANCE GLOBAL GROUP, INC. What’s Inside Financial Highlights 1 Chairman’s Message 2 View from the Top 6 AGI Subsidiaries 8 AGI at a Glance 10 AGI Milestones 12 Living the Dream 14 Working Hand in Hand 20 Enthralling Sights and Sounds 24 Holiday Stay Made Unforgettable 30 Exhilarating Experience 36 Spirit of Excellence 40 Taking a Bigger Bite 46 Enabling Interactive Connectivity 52 Raising the Bar 56 Corporate Social Responsibility 62 Board of Directors 68 AGI Key Officers 72 Subsidiaries Top Management 74 Management’s Discussion Our Cover and Analysis 76 Financials 89 Like a perfect world of lush greenery, fresh air, and warm sunshine affectionately embracing all of nature’s creation, AGI is at the heart of everyday life. With all things nice and wonderful, it is about living and loving every moment in the world of AGI. ALLIANCE GLOBAL GROUP, INC. Financial Highlights 17% 10-year 2018 156.8 CAGR* 2017 138.8 2016 132.9 2015 139.1 2014** 124.9 2013** 119.7 2012 102.1 2011 63.0 2010 44.5 Revenues billion Pesos In 2009 37.3 20% 2018 41.4 10-year 2017 40.6 CAGR* 2016 38.6 2015 35.9 ** 2014 35.0 2013** 33.4 1 2012 32.4 2011 18.9 2010 14.5 2009 8.9 EBITDA billion Pesos In 22% 2018 15.1 8.6 23.7 10-year CAGR* 2017 15.2 7.1 22.3 2016 14.9 8.0 22.9 2015 14.0 7.7 21.7 2014** 13.2 7.7 20.9 2013** 13.8 5.6 19.4 2012 13.9 6.6 20.5 2011 9.8 1.8 11.6 2010 6.9 2.6 9.5 2009 3.2 2.0 5.2 Net Profit Net billion Pesos In Owners of AGI Non-controlling interest Data shown for 2016 and 2017 are restated. -

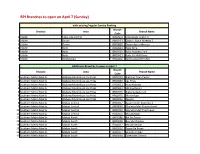

BPI Branches to Open on April 7 (Sunday)

BPI Branches to open on April 7 (Sunday) with existing/regular Sunday Banking Branch Division Area Branch Name Code 1 VisMin Cebu City Central BR00979 Cebu Ayala Center II 2 VisMin Davao BR00223 Davao - Ayala Abreeza 2 3 VisMin Davao BR00809 Davao Ayala Abreeza 4 VisMin Iloilo BR00914 Iloilo Atria 5 VisMin Iloilo BR00930 Iloilo Business Park 6 VisMin Iloilo BR00923 Iloilo GT Mall Pavia 7 VisMin Zamboanga BR00940 Zamboanga KCC Mall Additional Branches to open on April 7 Branch Division Area Branch Name Code 1 Southern Metro Manila Alabang Muntinlupa Las Pinas BR00159 Alabang Town Center 2 Southern Metro Manila Alabang Muntinlupa Las Pinas BR00830 Las Pinas 3 Southern Metro Manila Alabang Muntinlupa Las Pinas BR00033 New Alabang 4 Southern Metro Manila Alabang Muntinlupa Las Pinas BR00833 SM Southmall 5 Southern Metro Manila Alabang Muntinlupa Las Piñas BR00374 Alabang Ayala Life 6 Southern Metro Manila Alabang Muntinlupa Las Piñas BR00316 Muntinlupa 7 Southern Metro Manila Alabang Muntinlupa Las Piñas BR00023 Zapote 8 Southern Metro Manila Makati Central BR00247 Ayala Center Glorietta 3 9 Southern Metro Manila Makati Central BR00006 Glorietta Mall Ground Level 10 Southern Metro Manila Makati Central BR00453 Glorietta Mall Third Level 11 Southern Metro Manila Makati Central HO02001 Makati Main 12 Southern Metro Manila Makati North BR00186 Bel Air Paseo 13 Southern Metro Manila Makati North BR00028 Buendia Reposo 14 Southern Metro Manila Makati North BR00312 Makati Atrium 15 Southern Metro Manila Makati North BR00302 Paseo De Roxas 16 Southern -

Hotel Address Contact Number Email

HOTEL ADDRESS CONTACT NUMBER EMAIL Astoria Bohol Baranggay Taguihon, Baclayon, Bohol 335-1111 [email protected] 036-2881111/ Astoria Boracay Station 1, Boracay Island, Malay, Aklan [email protected] 036-2883536 Km 62 North National Highway, Brgy. San Rafael, Puerto Princesa Astoria Palawan 335-1111 [email protected] City, Palawan Astoria Plaza 15 J. Escriva Drive, Ortigas Business District, Pasig City 335-1131 to 35 [email protected] 2107 Prime Street, Madrigal Business Park, Ayala Alabang, B Hotel Alabang 828-8181 Muntinlupa City B Hotel Quezon City 14 Scout Rallos Street, Brgy. Laging Handa, Quezon City 990-5000 Chardonnay by Astoria 352 Captain Henry P. Javier, Brgy. Oranbo, Pasig City 335-1131 to 35 [email protected] Asean Avenue corner Roxas Boulevard, Entertainment City, City of Dreams Manila 800-8080 [email protected] Paranque Conrad Manila Seaside Boulevard, Coral Way, Pasay City 833-9999 Seascapes Resort Town, Soong, Lapu-Lapu City, Mactan Island, 032-4019999/ Crimson Resort & Spa Mactan [email protected] Cebu 239-3900 Ortigas Avenue corner Asian Development Bank Ave, Ortigas Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria 633-7222 Center, Quezon City Diamond Hotel Roxas Boulevard corner Dr. J. Quintos Street, Manila 528-3000/ 305-3000 [email protected] Discovery Suites 25 ADB Avenue, Ortigas Center, Pasig City 719-8888 [email protected] Dusit Thani Manila Ayala Center, Makati City 238-8888 [email protected] Eastwood Richmonde Hotel 17 Orchard Road, Eastwood City, Bagumbayan, Quezon City 570-7777 [email protected] F1 Hotel Manila 32nd Street, Bonifacio Global City, Taguig City 928-9888 Fairmont Makati 1 Raffles Drive, Makati Avenue, Makati City 795-1888 [email protected] Las Casas Filipinas de Acuzar Brgy. -

Report on the Private Sector Learning Activity

REPORT ON THE PRIVATE SECTOR LEARNING ACTIVITY Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project CONTRACT NO. AID-492-H-15-00001 SEPTEMBER 29, 2016 This report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the International City/County Management Association and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. USAID Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project Page i Documentation Report on Private Sector Learning Activity, September 2016 REPORT ON THE PRIVATE SECTOR LEARNING ACTIVITY Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project CONTRACT NO. AID-492-H-15-00001 Program Title: USAID/SURGE Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Philippines Contract Number: AID-492-H-15-00001 Contractor: International City/County Management Association (ICMA) Date of Publication: September 29, 2016 USAID Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project Page i Documentation Report on Private Sector Learning Activity, September 2016 Contents I. Introduction 4 II. Design of the Forum 5 III. Participants 5 IV. Implications on the Project 5 V. Next Steps 7 Tables Table 1. Batangas City Output of Workshop 1: Business Attraction and Expansion Opportunities and Challenges 25 Table 2. Batangas City Output of Workshop 2: Private Sector Agenda for Inclusive and Resilient Economic Growth in Cities 26 Table 3. Puerto Princesa City Output of Workshop 1: Business Attraction and Expansion Opportunities and Challenges 27 Table 4. Puerto Princesa City Output of Workshop 2: Private Sector Agenda for Inclusive and Resilient Economic Growth in Cities 28 Table 5. -

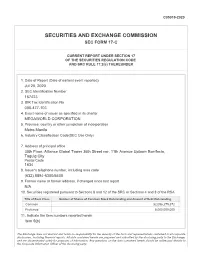

Securities and Exchange Commission Sec Form 17-C

C05019-2020 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM 17-C CURRENT REPORT UNDER SECTION 17 OF THE SECURITIES REGULATION CODE AND SRC RULE 17.2(c) THEREUNDER 1. Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported) Jul 20, 2020 2. SEC Identification Number 167423 3. BIR Tax Identification No. 000-477-103 4. Exact name of issuer as specified in its charter MEGAWORLD CORPORATION 5. Province, country or other jurisdiction of incorporation Metro Manila 6. Industry Classification Code(SEC Use Only) 7. Address of principal office 30th Floor, Alliance Global Tower 36th Street cor. 11th Avenue Uptown Bonifacio, Taguig City Postal Code 1634 8. Issuer's telephone number, including area code (632) 8894-6300/6400 9. Former name or former address, if changed since last report N/A 10. Securities registered pursuant to Sections 8 and 12 of the SRC or Sections 4 and 8 of the RSA Title of Each Class Number of Shares of Common Stock Outstanding and Amount of Debt Outstanding Common 32,056,275,872 Preferred 6,000,000,000 11. Indicate the item numbers reported herein Item 9(b) The Exchange does not warrant and holds no responsibility for the veracity of the facts and representations contained in all corporate disclosures, including financial reports. All data contained herein are prepared and submitted by the disclosing party to the Exchange, and are disseminated solely for purposes of information. Any questions on the data contained herein should be addressed directly to the Corporate Information Officer of the disclosing party. Megaworld Corporation MEG PSE Disclosure Form 4-31 - Press Release References: SRC Rule 17 (SEC Form 17-C) Section 4.4 of the Revised Disclosure Rules Subject of the Disclosure Press Release: "MEGAWORLD LAUNCHES 6TH RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT IN ILOILO BUSINESS PARK" Background/Description of the Disclosure Please see attached Press Release. -

Mice / Event Stakeholders and Partnership

UNIT OF COMPETENCY: MANAGE STAKEHOLDERS AND PARTNERSHIP _________________________________________________________________ CHAPTER II: MICE / EVENT STAKEHOLDERS AND PARTNERSHIP Learning Objectives: 1. Identify the market of MICE/Event 2. Examine the role of each stakeholders and partners STAKEHOLDERS Are the entities who are involved with the MICE/Events The level of influence on the MICE will depend on such factors as: • Motives (financial, emotional, political, or social) • Power and Authority • Resources • Degree of involvement PARTNERSHIP Formed among the stakeholders could be through a mix public and private involvement. STAKEHOLDERS CLIENTS INDEPENDENT ORGANIZERS INTERMEDIARIES SUPPLIERS CLIENTS – are the source of revenue of the event, they are the buyer who gives the final approval to host events and the main celebrator. The segment of clients are Individuals and Families, organizations/companies and public sector. Public Sector – this represent a broad cross- section of buyers, from government institutions and agencies, to local government unit who host civic events. Individuals and Families are typical prospects for life-cycle events. These clients normally hold parties to celebrate and to commune and rekindle relationships. Even wakes and funerals are now well orchestrated events. Organizations/Companies – are typical prospects for events to convene and for commerce, commonly referred to be a corporate event. They compose the market for meetings, seminars, conferences, conventions, product launches, bazaars, selling events, sales promotion activities, incentive trips and recreational activities THIS SEGMENT CAN BE FURTHER DIVIDED INTO: 1. Companies and Business establishments - These firms can either be sole proprietorship, partnerships or corporations whose main business can be retail, manufacturing or service. Events of these firms are part of the operating calendar or in response to the demand for their products or even to help to achieve the corporate objectives and support the management functions. -

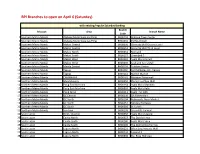

BPI Branches to Open on April 6 (Saturday)

BPI Branches to open on April 6 (Saturday) with existing/regular Saturday Banking Branch Division Area Branch Name Code 1 Southern Metro Manila Alabang Muntinlupa Las Piñas BR00159 Alabang Town Center 2 Southern Metro Manila Alabang Muntinlupa Las Piñas BR00833 SM Southmall 3 Southern Metro Manila Makati Central BR00006 Glorietta Mall Ground Level 4 Southern Metro Manila Makati Central BR00453 Glorietta Mall Third Level 5 Southern Metro Manila Makati North BR00352 Rockwell 6 Southern Metro Manila Makati South BR00157 Greenbelt 5 7 Southern Metro Manila Makati West BR00303 Ayala Malls Circuit 8 Southern Metro Manila Makati West BR00430 Cash and Carry Mall 9 Southern Metro Manila Manila Central BR00174 Tutuban Center 10 Southern Metro Manila Taguig BR01004 Fort Mckinley Hill- Venice 11 Southern Metro Manila Taguig BR00161 Market Market 12 Northern Metro Manila CAMANAVA BR00462 Malabon Fishermall 13 Northern Metro Manila Mandaluyong BR00250 Shangri-La Plaza Mall 14 Northern Metro Manila Pasig East Marikina BR00164 Ayala Malls Marikina 15 Northern Metro Manila Pasig East Marikina BR00804 Ayala Malls Feliz 16 Northern Metro Manila Pasig West BR00411 Ayala The 30th 17 Northern Metro Manila QC Central BR00446 QA Fisher Mall 18 Northern Metro Manila QC North BR00194 Robinson's Nova Market 19 Northern Metro Manila QC North BR00451 Fairview Terraces 20 Northern Metro Manila QC South BR00389 St. Luke's 21 Northern Metro Manila San Juan BR00193 Greenhills Unimart 22 South Luzon Bicol / Quezon BR00066 Ayala Malls Legazpi 23 South Luzon Cavite North BR00357 The District Imus 24 South Luzon Cavite South BR00180 Ayala Malls Serin 25 South Luzon Cavite South BR00285 The District Dasmarinas 26 South Luzon Laguna North BR00221 Biñan Southwoods Mall 27 South Luzon Laguna North BR00233 Solenad 3 28 South Luzon Laguna North BR00898 Sta. -

Securities and Exchange Commission

00111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 ' 110192018001895 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC Building,EDSA ,Greenh ills,MandaluyongCity,MetroManila, Philippines Tel:(632) 726-0931 to 39 Fax:(632) 725-5293 Email: [email protected] Barcode Page The following document has been received: Receiving Officer/Encoder : Buen Jose Mose - COS Receiving Branch : SEC Head Office Receipt Date and Time : October 19, 2018 03:13:16 PM Received From Head Office Company Representative Doc Source I Company Information SEC Registration No. 0000167 423 Company Name MEGAWORLD CORP. Industry Classification Company Type Stock Corporation Document Information Document ID 110192018001895 Document Type 17 -C (FORM 11-C:CURRENT DISCL/RPT) Document Code 17-C Period Covered October 16, 2018 No. of Days Late 0 Department CFD Remarks C06923-2018 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM 17-C CURRENT REPORT UNDER SECTION 17 OF THE SECURITIES REGULATION CODE AND SRC RULE 17.2(c) THEREUNDER 1. Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported) Oct 16, 2018 2. SEC Identification Number 167423 3. BIR Tax Identification No. 000-477-103 4. Exact name of issuer as specified in its charter MEGAWORLD CORPORATION 5. Province, country or other jurisdiction of incorporation Metro Manila 6. Industry Classification Code(SEC Use Only) 7. Address of principal office 30th Floor, Alliance Global Tower, 36th Street cor. 11th Avenue Uptown Bonifacio, Taguig City Postal Code 1634 8. Issuer's telephone number, including area code (632) 894-6300/6400 9. Former name or former address, if changed since last report N/A 10. Securities registered pursuant to Sections 8 and 12 of the SRC or Sections 4 and 8 of the RSA Title of Each Class Number of Shares of Common Stock Outstanding and Amount of Debt Outstanding Common 32,239,445,872 Preferred 6,000,000,000 11. -

United Architects of the Philippines Monthly Chapter

UNITED ARCHITECTS OF THE PHILIPPINES The Integrated and Accredited Professional Organization of Architects UAP National Headquarters, 53 Scout Rallos Street, Quezon City, Philippines MONTHLY CHAPTER ACTIVITY & ACCOMPLISHMENT REPORT Chapter UAP ILOILO CHAPTER MONTH OF OCTOBER 2019 Chapter President RODERICK G. TIAMSON Contact Numbers 0921-721 5506 DATE NOVEMBER 1, 2019 Email Address [email protected] SUBMITTED CHAPTER ACTIVITIES UNDERTAKEN DURING THE MONTH Indicate your chapter activities undertaken during the month such as Chapter GMM, Professional Development Seminars, Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives, etc ACTIVITY NO.1 WESTERN VISAYAS TRAINING OF TRAINERS Title of Activity Date September 30-October 4, 2019 ON CULTURAL MAPPING Jalaur Conference Room, NEDA-VI Building Twenty-two (22) Participants Venue Fort San Pedro Total Attendees Iloilo City Objective of the Activity PROMOTINGTHE ARCHITECTURE PROFESSION/HERITAGE CONSERVATION ADVOCACY Type of Activity GMM X Seminar X Socio-Civic Others: Activity in line with 4Ps Profession Professional X Professional Organization Professional Product Activity in support of the United Able X Proactive UAP corporate thrust PARTICIPANTS OF THE WESTERN VISAYAS TRAINING OF TRAINERS ON CULTURAL MAPPING NEDA WESTERN VISAYAS CONDUCTS TRAINING OF TRAINERS ON CULTURAL MAPPING The NEDA Regional Office in Western Visayas (NRO VI), in collaboration with the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), conducted the first Western Visayas Training of Trainers on Cultural mapping for local development planners and implementers in the region on September 30 to October 4, 2019. The event aimed to create a core set of regional trainers on cultural mapping. A total of 22 participants attended the the training composed of Provincial Tourism and Planning Officers from the Province of Antique, Capiz, Guimaras and Iloilo, and the cities of Iloilo and Bacolod.