The Digital Lives of Refugees: How Displaced Populations Use Mobile Phones and What Gets in the Way

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Refugee Committee

Job Description Position Title: - Communication Officer Department/Country Program: South East Asia Program – Thailand Country Office Report to: Project Manager Status (full, part-time, temporary): Full-time Duty station: Bangkok, Thailand Supervisory Capacity: None Department/Country Program Description/Mission Since 1978Alight, formerly known as American Refugee Committee (ARC), has provided life-saving primary health services for refugees, internally displaced persons (IDPs), and host communities in emergency and post-conflict settings around the world. Since 1995, Alight has expanded its portfolio to include countries transitioning to longer-term development. From the program’s inception, Alight strives to build host country capacity to provide a broad range of comprehensive health care services by supporting Ministries of Health, service providers, and local communities. Alight implements innovative and inclusive solutions to ensure that all beneficiaries have ready and equal access to health care. Alight has been working in Thailand for over 30 years with camp-based refugees from Myanmar and mobile migrant population since 2004, with current projects mostly focusing in malaria interventions along Thailand Myanmar borders. In the health sector, Alight provides an essential package of primary, reproductive, maternal, and child healthcare services in several refugee camps along the border with Myanmar, providing supplies, training, and supervision of refugee staff, along with community-based education. Primary Purpose of the Position Alight is re-awarded as a Sub Recipient of the Global Fund RAI3E regional component to host the regional malaria Civil Society Organization (CSO) platform, GMS for 2021-2023. The Regional Malaria CSO Platform is a network of civil society organizations from the Global Fund RAI implementing countries: Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Lao PDR and Vietnam. -

Eliminating Violence Against Women

ELIMINATING VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN PERSPECTIVES ON HONOR-RELATED VIOLENCE IN THE IRAQI KURDISTAN REGION, SULAIMANIYA GOVERNORATE By Tanyel B. Taysi With Contributions from Norul M. Rashid Martin Bohnstedt ASUDA & UNAMI HUMAN RIGHTS OFFICE: ELIMINATING VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN FOREWORD ......................................................................................................................................3 I. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................................4 II. INTERNATIONAL, REGIONAL AND NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS FRAMEWORKS .......................8 III. HONOR-RELATED VIOLENCE..................................................................................................14 IV. CONTEXTUAL OVERVIEW OF WOMEN’S POSITION IN IRAQI KURDISTAN ............................16 V. FINDINGS ...................................................................................................................................19 VI. SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................41 VII. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS .............................................................................43 APPENDIX.......................................................................................................................................48 Honor-related Violence in the Kurdistan Region Page 2 ASUDA & UNAMI HUMAN RIGHTS OFFICE: ELIMINATING VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN FOREWORD Honor-related -

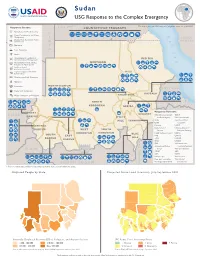

BHA Sudan Complex Emergency Fact Sheet

Sudan USG Response to the Complex Emergency This map represents USG-supported programs active as of 08/16/21. Response Sectors: EGYPT COUNTRYWIDE PROGRAMS Agriculture and Food Security LIBYA Camp Coordination and Camp R Management SAUDI Disaster Risk Reduction Policy e and Practice ARABIA Education d Food Assistance S Health e Humanitarian Coordination RED SEA and Information Management a Humanitarian Policy, Studies, NORTHERN Analysis, or Applications Livelihoods and Economic Recovery Logistics Support and Relief NILE Commodities Multipurpose Cash Assistance Nutrition Protection NORTH DARFUR ERITREA Shelter and Settlements KASSALA Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene KHARTOUM NORTH KORDOFAN GEZIRA WEST Response Partners: CHAD GEDAREF Adventist Development OCHA DARFUR WHITE and Relief Agency Relief International NILE SENNAR Alight Save the Children CARE Federation CENTRAL Concern UNDP Catholic Relief UN Department of DARFUR WEST SOUTH Services Safety and Security KORDOFAN KORDOFAN BLUE Danish Refugee Council UNFPA SOUTH EAST FAO UNHAS DARFUR NILE GOAL UNHCR DARFUR ETHIOPIA ICRC UNICEF IFRC Vétérinaires sans Abyei Area- International Medical Frontières/Germany C.A.R. Disputed* Corps War Child Canada iMMAP WFP IOM WHO Mercy Corps World Vision Near East Foundation World Relief SOUTH SUDAN Norwegian Church Aid International * Final sovereignty status of Abyei Area pending negotiations between South Sudan and Sudan. Displaced People by State Projected Acute Food Insecurity, July-September 2021 Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), Refugees, and Asylum-Seekers IPC Acute Food Insecurity Phase 1,000 - 100,000 250,001 - 500,000 1: Minimal 3: Crisis 5: Famine 100,001 - 250,000 Over 500,000 2: Stressed 4: Emergency Sources: Humanitarian Needs Overview, July 2020; UNHCR Population Dashboard, June 2021 Source: FEWS NET, Sudan Outlook, July - September 2021 The boundaries and names used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. -

Mahama Refugee Camp Profile Rwanda

Rwanda Mahama Refugee Camp Profile as of 09 April 2021 Population : 47,695 (Congolese: 4,190 Burundians: 43,500 Others: 5) CAMP OVERVIEW CURRENT SERVICES BACKGROUND SITUATION Coordinates : The following services are available in the camp: Lat:-2.30 S2o18’18.294” Mahama camp covering 175Ha of land with a total of 6,907 duplex family shelters that accommodates 52,026 persons and 2 durable 2 health centres, 2 primary schools and 2 secondary schools, 6 youth Long:30.8 E 30o50’17.904” communal accommodation blocks constructed in the camp to support Camp Extent : 175 Hectares centres, 1 women centre, 2 multi purpose vocational training centres, 2 accommodate new arrivals before being relocated to empty shelters Av. Camp Area/Person 2 34 m food distribution centres, 1 LPG distribution centre, 1 Police post; 3 camp within the camp. Distance from border : 30 km based markets, 1 community centre. Region/District : Kirehe # of Partners : 15 Admin divisions : 9 Quartiers (18 villages) Authority : Ministry in Charge of COMMUNITY ORGANIZATION Emergency Management (MINEMA) Government of Rwanda The camp community organization is structured around three administrative layers, which are Quartier, villages and communities. Each organizational level has its elected representatives, 18 village leaders and 9 zone leaders. Both men and women are proactively incorporated in all stages of electral process. SECTOR OVERVIEW Minimum DEMOGRAPHY Sector Indicator Target Achieved Standard Key Figures Age and Gender Refugees % of identified SGBV survivors offered multi-sectorial/appropriate -

Unhcr and Partner Practices Of

UNHCR AND PARTNER PRACTICES OF COMMUNITY-BASED PROTECTION ACROSS SECTORS IN THE EAST AND HORN OF AFRICA AND THE GREAT LAKES REGION SUGGESTED CITATION Charles Mballa, Josephine Ngebeh, Machtelt De Vriese, Katie Drew, Abigayil Parr, Chi-Chi Undie. 2020. UNHCR and Partner Practices of Community-Based Protection across Sectors in the East and Horn of Africa and the Great Lakes Region. UNHCR and Population Council. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS 2 FOREWORD 3 INTRODUCTION 4 METHODOLOGY 5 HIGHLIGHTS OF PROMISING PRACTICES 7 COMPENDIUM OF PRACTICES 9 COVID-RELATED PRACTICES 9 1. CHILD PROTECTION AND YOUTH 9 2. COMMUNITY-BASED PROTECTION 35 3. SGBV/RISK MITIGATION/RESPONSE 26 NON-COVID-RELATED PRACTICES 28 1. CHILD PROTECTION AND YOUTH 28 2. COMMUNITY-BASED PROTECTION 35 3. GENDER EQUALITY 51 4. SGBV/RISK MITIGATION/RESPONSE 54 1 UNHCR AND PARTNER PRACTICES OF COMMUNITY-BASED PROTECTION ACROSS SECTORS IN THE EAST AND HORN OF AFRICA AND THE GREAT LAKES REGION ACRONYMS AGD Age, Gender, and Diversity ARRA Agency for Refugee and Returnee Affairs CBAC Community-Based Adolescent Committee CBP Community-Based Protection CCCT Community Care Coalition Team CHH Child-Headed Household CHW Community Health Worker CORPS Community Owned Resource Person CPC Child Protection Committee CPV Child Protection Volunteer CRRF Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework CWC Child Welfare Committee DICAC Development and Inter-Church Aid Commission DRC Danish Refugee Council DHR Direction de l’Hydraulique Rurale EHAGL East and Horn of Africa and the Great Lakes FDP Food Distribution -

Amnesty International VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN

Amnesty International VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN Human Rights Education Activities for use in teaching Personal Social and Health Education, Citizenship and English for ages 11-18 HUMAN RIGHTS EDUcation RESOURCE WOMEN’S RIGHTS SECTION 2 The activities in this section are: ACTIVITY 1 Facts about violence against women Ages: 11+ 4 ACTIVITY 2 Is this OK? Ages: 11+ 7 ACTIVITY 3 Domestic violence Ages: 11+ 8 ACTIVITY 4 Problem, what problem? Ages: 15+ 11 ACTIVITY 5 Rape Ages: 15+ 13 ACTIVITY 6 Campaigns to stop gender violence Ages: 15+ 16 One important issue, not covered by any specific activity in this section, but referred to in the text, is Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). You can find information on this subject on these websites: http://www.stopfgmc.org/ www.ipu.org/wmn-e/fgm.htm www.amnesty.org.uk/education TEACHE INTRODUCTION FOR TEACHERS ‘Violence against women is perhaps the most shameful human rights violation, and it is perhaps the most pervasive. It knows no boundaries of geography, culture or wealth. As long as it R continues, we cannot claim to be making real progress towards NOTES equality, development and peace.’ Kofi Annan, UN Secretary General All human rights issues affect women. The activities in this resource comprises However, women also suffer specific denial the second in a series of three sets of of their human rights because of their activities on women and human rights that gender. The experience or threat of violence aim to help students to think about violence affects the lives of millions of women against women as a human rights issue, and everywhere, cutting across boundaries of to explore its causes and consequences: age, wealth, race, religion, sexual identity and culture. -

2021 South Sudan Regional Refugee Response Plan

SOUTH SUDAN REGIONAL REFUGEE RESPONSE PLAN January 2020 — December 2021 Updated in March 2021 CREDITS: UNHCR wishes to acknowledge the contributions of partners and staff in the field, Regional Bureau in Nairobi and Headquarters who have participated in the preparation of the narrative, financial and graphic components of this document. Production: UNHCR, Regional Bureau for East and Horn of Africa, and the Great Lakes The maps in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of UNHCR concerning the legal status of any country or territory or area, of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers or boundaries. All statistics are provisional and subject to change. For more information on the South Sudan crisis go to: South Sudan Information Sharing Portal FRONT COVER PHOTOGRAPH: South Sudanese refugees walk through Jewi refugee camp in Ethiopia. ©UNHCR / Eduardo Soteras Jalil SOUTH SUDAN REGIONAL RRP Contents Regional Refugee Response Plan 3 Foreword 4 Introduction 7 Regional Protection and Solutions Analysis 11 Regional Response Strategy and Priorities 14 Partnership and Coordination 20 Financial Requirements 22 The Democratic Republic of the Congo - summary plan Background 31 Needs Analysis 32 Response Strategy and Priorities 34 Partnership and Coordination 35 Financial Requirements 36 Ethiopia - summary plan Background 39 Needs Analysis 41 Response Strategy and Priorities 43 Partnership and Coordination 44 Financial Requirements 45 Kenya - summary plan Background 48 Needs Analysis 49 Response Strategy and -

(DFAT) Country Information Report on Sri Lanka of 4 November 2019

July 2020 Comments on the Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s (DFAT) Country Information Report on Sri Lanka of 4 November 2019 Contents About ARC ................................................................................................................................... 2 Introductory remarks on ARC’s COI methodology ......................................................................... 3 General methodological observations on the DFAT Country report on Sri Lanka ............................ 5 Section-specific observations on the DFAT Country report on Sri Lanka ....................................... 13 Economic Overview, Economic conditions in the north and east ........................................................ 13 Security situation, Security situation in the north and east ................................................................. 14 Race/Nationality; Tamils ....................................................................................................................... 16 Tamils .................................................................................................................................................... 20 Tamils: Monitoring, harassment, arrest and detention ........................................................................ 23 Political Opinion (Actual or Imputed): Political representation of minorities, including ethnic and religious minorities .............................................................................................................................. -

Southern Sudan

Southern Sudan Operational highlights Persons of concern • UNHCR facilitated the return of more than 26,000 Please refer to the Sudan (annual programme) chapter refugees and over 4,000 internally displaced people (IDPs) to their places of origin. • The Government of Sudan and UNHCR signed Working environment tripartite agreements on the voluntary repatriation of Sudanese refugees with the Governments of Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of the The signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement Congo and the Central African Republic. (CPA) between the Government of Sudan and the Sudan • The Office implemented more than 100 small People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) on community-based reintegration projects in areas with 9 January 2005 ended more than two decades of many returnees. The projects also benefited the conflict in Southern Sudan and raised hopes for the receiving communities. economic and social recovery of the country. Despite • UNHCR strengthened returnee monitoring and delays in the implementation of key aspects of the CPA, conducted 300 village assessments, which enabled the outlook today remains optimistic. refugees to receive timely and accurate information on conditions of return, besides allowing returnees to After the formation of the Government of National Unity and voice their protection concerns. the Government of Southern Sudan in September 2005, 218 UNHCR Global Report 2006 the United Nations and other organizations progressively Increased engagement with IDPs by UNHCR and its established their presence in Juba, the capital. partners and the establishment of State-based protection UNHCR’s operations, however, faced considerable working groups chaired by UNHCR helped to monitor challenges in 2006, most notably related to security. -

Kigeme Refugee Camp Profile Rwanda

Rwanda Kigeme Refugee Camp Profile as of 15 April 2021 Population : 17,694 (Congolese: 17,681 Burundi: 4 RWANDA: 9) CAMP OVERVIEW CURRENT SERVICES BACKGROUND SITUATION Coordinates : Lat 2°48’57.30”S The following services are available in the camp: Lon 29°52’41.94”E The government agency (MINEMA) allocated 34 hectares for 1 Health Clinic, 2 youth centres, 01 Women Centre, 01 community based housing refugees and building the assistance structures. Camp Extent : 34 Hectares rehabilitation centres, 1 food/NFI distribution centre, 1 police posts; 1 MINEMA administers the camp and is responsible for security Av. Camp Area/Person 2 191.417 m km (Nord-Kivu), 122.2 Km camp based market, 01 ECD (Early Childhoold Development) centres, 02 and protection of the refugees in coordination with UNHCR. Distance from border : (South Kivu) CFS (Child Friendly Space), 01 IP (Implementing Partner) Office, 01 Kigeme was established in 2012. Province/District : Southern / Nyamagabe MINEMA & Immigration Office, 01 Refugee Commitee Office, 01 UNHCR # of Partners : 10 Office, 61 solar streets lights, 01 Football playground, 01 Basketball/Volleyball Admin divisions : 14 Zones playground. Authority : Ministry of Emergency Management (MINEMA) - Government of Rwanda COMMUNITY ORGANIZATION The camp community organization is structured around 2 administrative layers, Kigeme which are Site (A&B), Quarters and villages . Each organizational level has its Refugee Camp elected representatives with currently 08 executive and quarters leaders, 27 village leaders. Both men -

Nyabiheke Refugee Camp Profile Rwanda

Rwanda Nyabiheke Refugee Camp Profile as of 31 March 2021 Population : 14,507 (Congolese: 14,499 Burundians: 8 ) CAMP OVERVIEW CURRENT SERVICES BACKGROUND SITUATION Coordinates : Lat 1°35’46”S The following services are available in the camp: Nyabiheke camp was established in 2005 mainly to reduce the Lon 30°15’40”E 1 health centre, 1 youth centre, 2 inter agency help desks and information overcrowding in Gihembe and Kiziba camps. This population has Camp Extent : 35 Hectares experienced multiple and/or prolonged displacement and is in need 2 centres, 1 women centre, 1 distribution site, 1 nutrition centre, 1 camp based Av. Camp Area/Person 45 m market, 1 community based rehabilitation centre, 1 library, 1 child friendly of durable solutions. Distance from border : 81.4 km space, 1 girls' safe space, 1 site for interview, complaints and feedback Of the three traditional durable solutions, resettlement in a third Region/District : Gatsibo/ Eastern Province mechanisms, 2 play grounds, 6 ECD classrooms, 62 solar streets lights country remains the most viable for the vast majority of the refugees # of Partners : 15 in Nyabiheke. In line with multi-year comprehensive solutions Admin divisions : COMMUNITY ORGANIZATION strategy, the Congolese resettlement programme will continue in Nyabiheke Authority : Ministry in Charge of Refugee Camp 2020 with 13,000 refugees identified to be still in need of Emergency Management The camp is divided into 8 quartiers and each quartier consists of approximately 4 resettlement. Following a reduced admissions ceiling to the USA for (MINEMA) - Government of villages giving a total of 29 villages. Each village has a 1 village leader. -

COVID-19 GLOBAL RESPONSE Situation Report Week 2 - March 23-29

COVID-19 GLOBAL RESPONSE Situation Report Week 2 - March 23-29 Emergency Preparedness No cases reported at clinics, refugee camps, or communities served. PEOPLE COVID-19 Confirmed • Virtual Covid-19 prevention training rolled out to all staff. 500 employees attend first two Cases in Alight countries: events. Translated briefings offered. • Recruitment focused health team pipeline Cambodia: 96 PROGRAM RESPONSE Colombia: 378 DRC: 48 Country Program COVID-19 Responses: El Salvador: 9 Sudan and Somalia have an incredibly high level of responsibility. Sudan health teams serve 1,500,000 people alone. Global health technical staff support surge Germany: 37.066 scenario planning and program design. Operations and logistics team focused on Jordan: 172 pre-position medicine and supplies. Recruitment focused on pipeline. Jack Ma, Ali Baba Founder, large shipment of emergency supplies lands in Somalia. Teams Kenya: 28 work to secure supplies for health facilities. Mexico: 405 Rwanda is the health lead in three refugee camps. Their role is to identify, isolate, Myanmar: 3 and transport people with Covid-19 symptoms to treatment facilities. Clinic preparedeness has been reviewed and approved by the Ministry of Health. The Pakistan: 1,022 team is now focused on securing funding for surge capacity. Rwanda: 40 Thailand + Myanmar have community-based health programs. Team are trained Somalia: 1 to identify and report cases. There is growing concern about protecting internally displaced communities. The begins to explore a community isolation South Sudan: 0 model. Sudan: 3 Uganda is the Protection lead in seven settlements. New arrival support, Syria: 5 counseling services, safe house and other critical services are ongoing.