Looking for Harmony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Refugee Committee

Job Description Position Title: - Communication Officer Department/Country Program: South East Asia Program – Thailand Country Office Report to: Project Manager Status (full, part-time, temporary): Full-time Duty station: Bangkok, Thailand Supervisory Capacity: None Department/Country Program Description/Mission Since 1978Alight, formerly known as American Refugee Committee (ARC), has provided life-saving primary health services for refugees, internally displaced persons (IDPs), and host communities in emergency and post-conflict settings around the world. Since 1995, Alight has expanded its portfolio to include countries transitioning to longer-term development. From the program’s inception, Alight strives to build host country capacity to provide a broad range of comprehensive health care services by supporting Ministries of Health, service providers, and local communities. Alight implements innovative and inclusive solutions to ensure that all beneficiaries have ready and equal access to health care. Alight has been working in Thailand for over 30 years with camp-based refugees from Myanmar and mobile migrant population since 2004, with current projects mostly focusing in malaria interventions along Thailand Myanmar borders. In the health sector, Alight provides an essential package of primary, reproductive, maternal, and child healthcare services in several refugee camps along the border with Myanmar, providing supplies, training, and supervision of refugee staff, along with community-based education. Primary Purpose of the Position Alight is re-awarded as a Sub Recipient of the Global Fund RAI3E regional component to host the regional malaria Civil Society Organization (CSO) platform, GMS for 2021-2023. The Regional Malaria CSO Platform is a network of civil society organizations from the Global Fund RAI implementing countries: Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Lao PDR and Vietnam. -

Rising Sinophobia in Kyrgyzstan: the Role of Political Corruption

RISING SINOPHOBIA IN KYRGYZSTAN: THE ROLE OF POLITICAL CORRUPTION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY DOĞUKAN BAŞ IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF EURASIAN STUDIES SEPTEMBER 2020 Approval of the thesis: RISING SINOPHOBIA IN KYRGYZSTAN: THE ROLE OF POLITICAL CORRUPTION submitted by DOĞUKAN BAŞ in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Eurasian Studies, the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Yaşar KONDAKÇI Dean Graduate School of Social Sciences Assoc. Prof. Dr. Işık KUŞÇU BONNENFANT Head of Department Eurasian Studies Prof. Dr. Pınar KÖKSAL Supervisor Political Science and Public Administration Examining Committee Members: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Işık KUŞÇU BONNENFANT (Head of the Examining Committee) Middle East Technical University International Relations Prof. Dr. Pınar KÖKSAL (Supervisor) Middle East Technical University Political Science and Public Administration Assist. Prof. Dr. Yuliya BILETSKA Karabük University International Relations I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Doğukan Baş Signature : iii ABSTRACT RISING SINOPHOBIA IN KYRGYZSTAN: THE ROLE OF POLITICAL CORRUPTION BAŞ, Doğukan M.Sc., Eurasian Studies Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Pınar KÖKSAL September 2020, 131 pages In recent years, one of the major problems that Kyrgyzstan witnesses is rising Sinophobia among the local people due to problems related with increasing Chinese economic presence in the country. -

Eliminating Violence Against Women

ELIMINATING VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN PERSPECTIVES ON HONOR-RELATED VIOLENCE IN THE IRAQI KURDISTAN REGION, SULAIMANIYA GOVERNORATE By Tanyel B. Taysi With Contributions from Norul M. Rashid Martin Bohnstedt ASUDA & UNAMI HUMAN RIGHTS OFFICE: ELIMINATING VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN FOREWORD ......................................................................................................................................3 I. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................................4 II. INTERNATIONAL, REGIONAL AND NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS FRAMEWORKS .......................8 III. HONOR-RELATED VIOLENCE..................................................................................................14 IV. CONTEXTUAL OVERVIEW OF WOMEN’S POSITION IN IRAQI KURDISTAN ............................16 V. FINDINGS ...................................................................................................................................19 VI. SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................41 VII. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS .............................................................................43 APPENDIX.......................................................................................................................................48 Honor-related Violence in the Kurdistan Region Page 2 ASUDA & UNAMI HUMAN RIGHTS OFFICE: ELIMINATING VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN FOREWORD Honor-related -

ELECTION OBSERVATION DELEGATION to the PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS in KYRGYZSTAN (4 October 2015) Report by Ryszard Czarnecki, Chair

ELECTION OBSERVATION DELEGATION TO THE PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS IN KYRGYZSTAN (4 October 2015) Report by Ryszard Czarnecki, Chair of the Delegation Annexes: A. Final programme (including list of participants) B. Statement of the Chair of the EP Delegation at the press conference C. IEOM Joint Press Statement D. IEOM Preliminary Findings and Conclusions Introduction Following an invitation sent by the President of the Parliament of the Kyrgyz Republic, the Conference of Presidents of the European Parliament authorised, on 10 September 2015, the sending of an Election Observation Delegation to observe the parliamentary elections in Kyrgyzstan scheduled for 4 October 2015. The European Parliament Election Observation Delegation was composed of six Members: Mr Ryszard Czarnecki (ECR, Poland), Mr Joachim Zeller (EPP, Germany), Mr Juan Fernando Lopez Aguilar (S&D, Spain), Ms Marietje Schaake (ALDE, Netherlands), Ms Tatjana Zdanoka (Greens/EFA, Latvia) and Mr Ignazio Corrao (EFDD, Italy). Mr Ryszard Czarnecki was elected Chair of the Delegation at the constituent meeting on 22 September 2015. The European Parliament Delegation performed the election observation in accordance with the Declaration of Principles of International Election Observation and the Code of Conduct for international election observers. It followed the OSCE/ODIHR's methodology in the evaluation procedure and assessed the election for its compliance with OSCE commitments for democratic elections. Members of the EP Delegation signed the Code of Conduct for Members of the European Parliament Election Observation Delegations, in conformity with the decision of the Conference of Presidents of 13 September 2012. Programme As is usual in the OSCE area, the Delegation was integrated within the framework of the OSCE/ODIHR election observation mission. -

Central Asia in a Reconnecting Eurasia Kyrgyzstan’S Evolving Foreign Economic and Security Interests

JUNE 2015 1616 Rhode Island Avenue NW Washington, DC 20036 202-887-0200 | www.csis.org Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 4501 Forbes Boulevard Lanham, MD 20706 301- 459- 3366 | www.rowman.com Central Asia in a Reconnecting Eurasia Kyrgyzstan’s Evolving Foreign Economic and Security Interests AUTHORS Andrew C. Kuchins Jeffrey Mankoff Oliver Backes A Report of the CSIS Russia and Eurasia Program ISBN 978-1-4422-4100-8 Ë|xHSLEOCy241008z v*:+:!:+:! Cover photo: Labusova Olga, Shutterstock.com. Blank Central Asia in a Reconnecting Eurasia Kyrgyzstan’s Evolving Foreign Economic and Security Interests AUTHORS Andrew C. Kuchins Jeffrey Mankoff Oliver Backes A Report of the CSIS Rus sia and Eurasia Program June 2015 Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 594-61689_ch00_3P.indd 1 5/7/15 10:33 AM hn hk io il sy SY eh ek About CSIS hn hk io il sy SY eh ek For over 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has worked to hn hk io il sy SY eh ek develop solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. Today, CSIS scholars are hn hk io il sy SY eh ek providing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart hn hk io il sy SY eh ek a course toward a better world. hn hk io il sy SY eh ek CSIS is a nonprofit or ga ni za tion headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full- time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analy sis and hn hk io il sy SY eh ek develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. -

Challenges to Freedom of Religion in Post-Soviet Central Asian States

MARCH 2016 Challenges to Freedom of Religion in Post-Soviet Central Asian States Religious Freedom Initiative Mission Eurasia VITALIY V. PROSHAK AND EVGENY GRECHKO www.MissionEurasia.org Challenges to Freedom of Religion in Post-Soviet Central Asian States Analytical Report Vitaliy V. Proshak and Evgeny Grechko Publication of Mission Eurasia Religious Freedom Initiatives March 2016 Foreword This year the global community marks 25 years since the disintegration of the USSR, which gave 15 Soviet socialist republics the freedom to determine their own political, economic, and religious identities. This includes the five former Soviet republics in the pre-dominantly Muslim region known as Central Asia, which share geographical borders and the same Soviet political and economic system that propagated atheism for more than 70 years. When the USSR collapsed, the religious groups most actively involved in outreach in Central Asia—evangelicals—were given the unprecedented opportunity to grow by reaching across ethnic boundaries with Christian values. However, this region’s deep historical Muslim roots joined with the vestiges of Soviet authoritarianism to establish strict control over the religious sphere and prevent the establishment of new democracies. It is interesting to note that the leaders of most Central Asian countries today are the same leaders who were in power in these countries during the Soviet era. Governments of the countries in Central Asia understand the threat that all religions, including radical Islam, pose to their power. For this reason, they have enacted legislation that strictly controls every aspect of religious life. Christianity, especially the evangelical church, has suffered the most, both because of its rejection by the predominantly Muslim culture and its outward focus on society. -

Strategic Nodes and Regional Interactions in Southern Eurasia

MARLENE Laruelle STRATEGIC editor NODES Central Asia Program REGIONAL Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies and INTERACTIONS Elliott School of International SOUTHERN A airs The George Washington University in EURASIA STRATEGIC NODES AND REGIONAL INTERACTIONS IN SOUTHERN EURASIA Marlene Laruelle, editor Washington, D.C.: The George Washington University, Central Asia Program, 2017 www.centralasiaprogram.org The volume provides academics and policy makers with an introduction to current trends in Southern Eurasia. At the collapse of the Soviet Union, Western pundits celebrated the dramatic reshaping of regional interactions in Southern Eurasia to come, with the hope of seeing Russia lose its influence and be bypassed by growing cooperation between the states of the South Caucasus and Central Asia, as well as the arrival of new external powers. This hope has partially failed to come to fruition, as regional cooperation between the South Caucasus and Central Asia never started up, and cooperation within these regions has been hampered by several sovereignty-related and competition issues. However, a quarter of century after the disappearance of the Soviet Union, strategic nodes in Southern Eurasia have indeed deeply evolved. Some bottom-up dynamics seem to have taken shape and the massive involvement of China has been changing the long-accepted conditions in the wider region. Islamic finance has also emerged, while external actors such as Turkey, Iran, the Gulf countries and Pakistan have progressively structured their engagement with both Central Asia and South Caucasus. Another key node is centered in and around Mongolia, whose economic boom and strategic readjustments may help to shape the future of Northeast Asia. -

India-Kyrgyz Republic Bilateral Relations

India-Kyrgyz Republic bilateral relations Historically, India has had close contacts with Central Asia, especially countries which were part of the Ancient Silk Route, including Kyrgyzstan. During the Soviet era, India and the then Kyrgyz Republic had limited political, economic and cultural contacts. Former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi visited Bishkek and Issyk-Kul Lake in 1985. Since the independence of Kyrgyz Republic on 31st August, 1991, India was among the first to establish diplomatic relations on 18 March 1992; the resident Mission of India was set up on 23 May 1994. Political relations Political ties with the Kyrgyz Republic have been traditionally warm and friendly. Kyrgyzstan also supports India’s bid for permanent seat at UNSC and India’s full membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Both countries share common concerns on threat of terrorism, extremism and drug–trafficking. Since the establishment of diplomatic relations in 1992, the two countries have signed several framework agreements, including on Culture, Trade and Economic Cooperation, Civil Aviation, Investment Promotion and Protection, Avoidance of Double Taxation, Consular Convention etc. At the institutional level, the 8th round of Foreign Office Consultation was held in Bishkek on 27 April 2016. The Indian delegation was led by Ms. Sujata Mehta, Secretary (West) and Kyrgyz side was headed by Mr. Azamat Usenov, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs. An Indo-Kyrgyz Joint Commission on Trade, Economic, Scientific and Technological Cooperation was set up in 1992. The 8th Session of India-Kyrgyz Inter- Governmental Commission on Trade, Economic, Scientific and Technological Cooperation was held in Bishkek on 28 November 2016. -

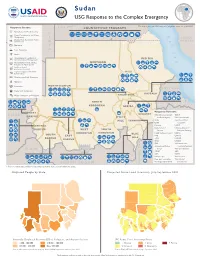

BHA Sudan Complex Emergency Fact Sheet

Sudan USG Response to the Complex Emergency This map represents USG-supported programs active as of 08/16/21. Response Sectors: EGYPT COUNTRYWIDE PROGRAMS Agriculture and Food Security LIBYA Camp Coordination and Camp R Management SAUDI Disaster Risk Reduction Policy e and Practice ARABIA Education d Food Assistance S Health e Humanitarian Coordination RED SEA and Information Management a Humanitarian Policy, Studies, NORTHERN Analysis, or Applications Livelihoods and Economic Recovery Logistics Support and Relief NILE Commodities Multipurpose Cash Assistance Nutrition Protection NORTH DARFUR ERITREA Shelter and Settlements KASSALA Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene KHARTOUM NORTH KORDOFAN GEZIRA WEST Response Partners: CHAD GEDAREF Adventist Development OCHA DARFUR WHITE and Relief Agency Relief International NILE SENNAR Alight Save the Children CARE Federation CENTRAL Concern UNDP Catholic Relief UN Department of DARFUR WEST SOUTH Services Safety and Security KORDOFAN KORDOFAN BLUE Danish Refugee Council UNFPA SOUTH EAST FAO UNHAS DARFUR NILE GOAL UNHCR DARFUR ETHIOPIA ICRC UNICEF IFRC Vétérinaires sans Abyei Area- International Medical Frontières/Germany C.A.R. Disputed* Corps War Child Canada iMMAP WFP IOM WHO Mercy Corps World Vision Near East Foundation World Relief SOUTH SUDAN Norwegian Church Aid International * Final sovereignty status of Abyei Area pending negotiations between South Sudan and Sudan. Displaced People by State Projected Acute Food Insecurity, July-September 2021 Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), Refugees, and Asylum-Seekers IPC Acute Food Insecurity Phase 1,000 - 100,000 250,001 - 500,000 1: Minimal 3: Crisis 5: Famine 100,001 - 250,000 Over 500,000 2: Stressed 4: Emergency Sources: Humanitarian Needs Overview, July 2020; UNHCR Population Dashboard, June 2021 Source: FEWS NET, Sudan Outlook, July - September 2021 The boundaries and names used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. -

Kyrgyzstan: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests

Kyrgyzstan: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Jim Nichol Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs August 30, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov 97-690 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Kyrgyzstan: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Summary Kyrgyzstan is a small and poor Central Asian country that gained independence in 1991 with the breakup of the Soviet Union. The United States has been interested in helping Kyrgyzstan to enhance its sovereignty and territorial integrity, bolster economic reform and development, strengthen human rights, prevent weapons proliferation, and more effectively combat transnational terrorism and trafficking in persons and narcotics. Special attention long has been placed on bolstering civil society and democratization in what has appeared to be the most receptive—but still challenging—political and social environment in Central Asia. The significance of Kyrgyzstan to the United States increased after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States. Kyrgyzstan offered to host U.S. forces at an airbase at the Manas international airport outside of the capital, Bishkek, and it opened in December 2001. The U.S. military repaired and later upgraded the air field for aerial refueling, airlift and airdrop, medical evacuation, and support for U.S. and coalition personnel and cargo transiting in and out of Afghanistan. The Kyrgyz government threatened to close down the airbase in early 2009, but renewed the lease on the airbase (renamed the Manas Transit Center) in June 2009 after the United States agreed to higher lease and other payments. President Almazbek Atambayev and the legislature have stated that the basing agreement will not be renewed when it expires in 2014. -

Mahama Refugee Camp Profile Rwanda

Rwanda Mahama Refugee Camp Profile as of 09 April 2021 Population : 47,695 (Congolese: 4,190 Burundians: 43,500 Others: 5) CAMP OVERVIEW CURRENT SERVICES BACKGROUND SITUATION Coordinates : The following services are available in the camp: Lat:-2.30 S2o18’18.294” Mahama camp covering 175Ha of land with a total of 6,907 duplex family shelters that accommodates 52,026 persons and 2 durable 2 health centres, 2 primary schools and 2 secondary schools, 6 youth Long:30.8 E 30o50’17.904” communal accommodation blocks constructed in the camp to support Camp Extent : 175 Hectares centres, 1 women centre, 2 multi purpose vocational training centres, 2 accommodate new arrivals before being relocated to empty shelters Av. Camp Area/Person 2 34 m food distribution centres, 1 LPG distribution centre, 1 Police post; 3 camp within the camp. Distance from border : 30 km based markets, 1 community centre. Region/District : Kirehe # of Partners : 15 Admin divisions : 9 Quartiers (18 villages) Authority : Ministry in Charge of COMMUNITY ORGANIZATION Emergency Management (MINEMA) Government of Rwanda The camp community organization is structured around three administrative layers, which are Quartier, villages and communities. Each organizational level has its elected representatives, 18 village leaders and 9 zone leaders. Both men and women are proactively incorporated in all stages of electral process. SECTOR OVERVIEW Minimum DEMOGRAPHY Sector Indicator Target Achieved Standard Key Figures Age and Gender Refugees % of identified SGBV survivors offered multi-sectorial/appropriate -

VULNERABLE to MANIPULATION Interviews with Migrant Youth and Youth Remittance-Recipients in the Kyrgyz Republic MAY 2016

Photo: Timothy Harris VULNERABLE TO MANIPULATION Interviews with Migrant Youth and Youth Remittance-Recipients in the Kyrgyz Republic MAY 2016 Executive Summary Research conducted by Mercy Corps and Foundation for Tolerance International (FTI) in Kyrgyzstan1 reveals a number of risk factors related to violence that exist within the studied youth population of southern Kyrgyzstan. This research was conducted between March and May 2016 in the southern provinces of Osh, Jalalabad, Batken, and in the northern province of Issyk-Kul. In 2010, southern Kyrgyzstan saw an outbreak of violence between ethnic Kyrgyz and ethnic Uzbek citizens. Known locally as the Osh Events, this violence resulted in mass casualties, displacement and destruction of physical infrastructure in the South. In addition, southern Kyrgyzstan is a known origin of people migrating to Syria to join Jabhat al-Nusra or the so-called Islamic State, with official figures citing fewer than 500 people from Kyrgyzstan.2 While this research did not specifically seek out people who migrated to join the fight in the Middle East, some respondents were directly aware of neighbors, friends, acquaintances or people from their communities who had gone. Issyk-Kul was selected as a comparator province for this study due to its multi-ethnic composition and lack of conflict history. Kyrgyzstan is characterized by a young, rapidly expanding population, high levels of rural poverty, insufficient domestic jobs for working-age people, and a high dependence on Russia as a source of remittances. The precipitous reduction in remittances from Russia due to contractions in the Russian economy in the last two years and changes in the ruble/som exchange rate have spurred questions about the population’s vulnerability to destabilization or recruitment to jihadi organizations.