Dublin Airport Operating Expenditure: Bottom-Up Efficiency Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Garda Síochána

An Garda Síochána Oifig an Choimisinéara Office of the Commissioner Gnóthaí Corparáideacha Corporate Affairs An Garda Síochána Garda Headquarters Páirc an Fhionnuisce Phoenix Park Baile Átha Cliath 8 Dublin 8 D08 HN3X D08 HN3X Láithreán Gréasáin / Website: www.garda.ie Luaigh an uimhir tharaghta seo a Ríomhpost / E-mail: leanas le do thoil: [email protected] Please quote the following ref. number: CMR_34-367274/15 Ms. Helen Hall Chief Executive Policing Authority Dear Helen Re: Commissioner’s Monthly Report to the Policing Authority __________________________________________________________________________________ I am pleased to provide the seventh monthly report for 2019 outlining the key aspects of the administration and operation of An Garda Síochána, in accordance with Section 41A of the Garda Síochána Act 2005, as amended. Additional and updated data continues to be included in response to requests of the Policing Authority during discussions at monthly meetings. As advised previously, reporting will continue through the Policing Strategy and Performance and the Organisation Development Committees to ensure the Authority is informed on all relevant projects in accordance with its oversight role. Project information not outlined in our core reporting will be provided as required. Yours sincerely J A HARRIS COMMISSIONER July 2019 An Garda Síochána: Ag Coinneáil Daoine Sábháilte – Keeping People Safe 1 Message from the Commissioner During the last month, An Garda Síochána demonstrated in a number of ways its commitment to becoming a more diverse organisation so it can fully reflect and represent the community it serves. The most visible of these was the participation by Garda members and staff, along with colleagues in the PSNI, in the annual Pride Parade. -

Draft Common Manual for Immigration Liaison Officers (Ilos) Posted Abroad by the Member States of the European Union

COUNCIL OF Brussels, 25 April 2006 THE EUROPEAN UNION 8418/06 LIMITE CIREFI 16 COMIX 368 NOTE from : General Secretariat to : CIREFI No. prev. doc.: 14759/05 CIREFI 31 COMIX 781 Subject : Draft Common Manual for Immigration Liaison Officers (ILOs) posted abroad by the Member States of the European Union Delegations will find attached the above-mentioned draft Common Manual. ______________ 8418/06 EB/cr 1 DG H I LIMITE EN DRAFT Common Manual For Immigration Liaison Officers posted abroad by the Member States of the European Union 2006 8418/06 EB/cr 2 DG H I LIMITE EN TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.......................................................................................................................5 2. Purpose, Nature And Scope of the Manual.......................................................................5 3. General Part.......................................................................................................................5 3.1 Organisations and persons concerned by this Manual ...............................................5 3.2 ILOs tasks and best practices .....................................................................................6 3.2.1. Constitution of cooperation networks between ILOs through networking activities....................................................................................6 3.2.2. Establish and maintain direct contacts with the competent authorities/ representatives of international organisations in the host country/ ILOs of third countries and commercial -

PRO IP Act Annual Report FY 2019

United States Department of Justice ____________________________ PRO IP Act Annual Report FY 2019 PRO IP ACT ANNUAL REPORT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL FY 2019 INTRODUCTION The Department of Justice (the “Department” or “DOJ”)1 submits this Fiscal Year 2019 (“FY 2019”) annual report to the United States Congress pursuant to Section 404 of the Prioritizing Resources and Organization for Intellectual Property Act of 2008 (“PRO IP Act” or “Act”), Pub. L. No. 110-403. The Act imposes a number of annual reporting requirements on the Attorney General, including actions the Department has taken to implement Title IV of the Act (“Department of Justice Programs”) and “a summary of the efforts, activities, and resources the [Department] has allocated to the enforcement, investigation, and prosecution of intellectual property crimes.” The Act requires similar reporting by the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”) on its intellectual property (“IP”) enforcement efforts pursuant to Title IV of the Act. To the extent a particular request seeks information maintained by the FBI, the Department respectfully refers Congress to the FBI Fiscal Year 2019 Report to Congress on Intellectual Property Enforcement (“FBI’s Annual Report”). 1 Appendix A contains a glossary of acronyms referenced throughout this report. PRO IP Act Annual Report FY 2019 1 Section 404(a) of the PRO IP Act requires the Attorney General to report annually to Congress on the Department’s efforts to implement eight specified provisions of Title IV during the prior fiscal year. Those provisions and the Department’s efforts to implement them during FY 2019 (i.e., October 1, 2018 through September 30, 2019) are set forth below. -

Building for the Future

Building for the future daa plc | daa cpt Annual Report 2018 daa plc | daa cpt Annual Report 2018 Strategic report Governance 77 Company balance sheet 2 2018 highlights 56 Board of Directors 78 Group statement of cash flows 6 About our business 58 Executive management team 79 Group statement of changes in equity 8 Our business at a glance 60 Governance report 80 Company statement of changes in equity 10 Chairman’s statement 68 Report of the Directors 81 Notes on and forming part of the 12 Chief Executive’s review financial statements 16 Our strategy Financial statements 116 Five-year summaries 22 Strategy in action 70 Directors’ responsibilities statement 119 Aeronautical information 28 Risk report 71 Independent auditor’s report 120 General business information 34 Operating review 74 Group profit and loss account 44 Chief Financial Officer’s review 75 Group statement of comprehensive income 50 Corporate responsibility 76 Group balance sheet 2 What we do We manage Dublin and Cork airports, and have overseas airport operations and investments in Cyprus, Germany and Saudi Arabia. Our travel retail subsidiary ARI has outlets in Europe, North America, the Middle East, India and Asia-Pacific. We also provide aviation advisory services. Find out more on page 6 1 Who we are We are a global airports and travel retail Group that has businesses in 13 countries. We are owned by the Irish State and headquartered at Dublin Airport. Our vision is to be airport industry leaders. Strategic report Governance 4 Our focus Financial statements on growth We look to grow our Group at home and abroad to increase the value of the business. -

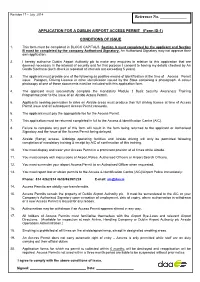

Application for Permanent Security Identity Pass

Revision 17 – July 2014 Reference No. _____________ APPLICATION FOR A DUBLIN AIRPORT ACCESS PERMIT (Form ID-1) CONDITIONS OF ISSUE 1. This form must be completed in BLOCK CAPITALS. Section A must completed by the applicant and Section B must be completed by the company Authorised Signatory. An Authorised Signatory may not approve their own application. 2. I hereby authorise Dublin Airport Authority plc to make any enquiries in relation to this application that are deemed necessary in the interest of security and for that purpose I consent to having my details checked by An Garda Siochana (such check is repeated at intervals not exceeding 5 years). 3. The applicant must provide one of the following as positive means of identification at the time of Access Permit issue: Passport, Driving Licence or other identification issued by the State containing a photograph. A colour photocopy of one of these documents must be included with this application form. 4. The applicant must successfully complete the mandatory Module 1 Basic Security Awareness Training Programme prior to the issue of an Airside Access Permit. 5. Applicants seeking permission to drive on Airside areas must produce their full driving licence at time of Access Permit issue and all subsequent Access Permit renewals. 6. The applicant must pay the appropriate fee for the Access Permit. 7. This application must be returned completed in full to the Access & Identification Centre (AIC). 8. Failure to complete any part of this form will result in the form being returned to the applicant or Authorised Signatory and the issue of the Access Permit being delayed. -

Dublin Airport Terminal 2 Operating Cost Assessment R01000

Booz & Company Dublin, 2009 Report Dublin Airport Terminal 2 Operating Cost Assessment R01000 6th November 2009 This document is confidential and is intended solely for the use and information of the client to whom it is addressed. This report was commissioned by, and prepared for, the Commission of Aviation Regulation (CAR) by Booz & Company (“The Consultant”). The findings and conclusions set forth in the report represent the best professional judgment of the Consultant based on information made available to it by the CAR and others. The Consultant has relied on, and not independently verified, data provided to it by such sources and on secondary sources of information cited in the report. We note that if the information provided to us by such sources or obtained from secondary sources proves to be incorrect, the conclusions stated in our report could also be incorrect. The report states a number of assumptions made during our analysis. While we have no reason to believe any of these assumptions are unreasonable, we note that if any prove incorrect, actual results could vary from those we have projected. Third parties to whom CAR may make this report available should not rely on the findings or conclusions set forth in this report without obtaining independent professional advice and undertaking their own due diligence. Any reliance on this report by a third party or any decisions made by any such third party based on this report, are the sole responsibility of such third party. The Consultants have not had and do not acknowledge any duty of care to any such third party with respect to the report, and shall have no financial or other liability to any such party with respect to any matter related to any decisions made by any such party, in whole or in part, on this report. -

Conference Booklet Pearls in Policing 2015

Conference booklet Pearls in Policing 2015 Copenhagen, Denmark 13-17 June 2015 ‘Shaping Innovation through Partnerships’ 2 Table of contents 1. Welcome by Commissioner Jens Henrik Højbjerg of the Danish National Police, Host Pearls in Policing 2015 2. Welcome by Commissioner Gerard Bouman of the Netherlands Police, on behalf of the Pearls Curatorium 3. Welcome on behalf of the Conference Co-Directors, Mr. Anders Dorph and Ms. Anita Hazenberg 4. Conference Programme Pearls in Policing 5. Peer to Peer Consultation 6. Participants Pearls in Policing 7. Academics Pearls in Policing 8. The International Pearl Fishers Action Learning Group (IALG) 9. Partner Programme 10. Pearls Curatorium 11. Board of International Advisors 12. Organisation of the Pearls in Policing Conference 13. Things you should know 14. Notes 3 4 Welcome by Commissioner Jens Henrik Højbjerg of the Danish National Police, Host Pearls in Policing 2015 On behalf of the Danish National Police I am Danish Police to raise the level of performance My hope for this conference and for the honoured and delighted to welcome you to significantly and has successfully been a future is, that we all will be brick makers and the city of Copenhagen for the 2015 Pearls in strong factor in producing results all over the join together in strengthening the foundation Policing Conference. organisation. for innovation - a necessity in order to meet I have been looking forward to this great the future requirements and challenges of opportunity to introduce you to our beautiful Innovations also require transparency, open- increasingly complex crime patterns, political capital, and I hope you will find the setting mindedness and willingness to look at others. -

Attorney General's Annual Report to Congress and Assessment of U.S

Attorney General’s Annual Report to Congress and Assessment of U.S. Government Activities to Combat Trafficking in Persons Fiscal Year 2014 Table of Contents I. Introduction .......................................................................................................................1 II. U.S. Governmental Measures and Activities Responding to FY 2014 Recommendations ..............................................................................................................6 III. FY 2015 Recommendations .............................................................................................23 IV. Benefits and Services Given Domestically to Trafficking Victims ..............................24 A. Department of Health and Human Services ..................................................................24 B. Department of Homeland Security ................................................................................36 C. Department of Justice ....................................................................................................38 D. Department of Labor .....................................................................................................48 E. Department of State .......................................................................................................49 F. Legal Services Corporation ...........................................................................................49 V. Immigration Benefits for Trafficking Victims ..............................................................50 -

Challenges for People with Intellectual Disabilities in Law Enforcement Interactions in Ireland; Thematic Analysis Informed by 1537 Person-Years’ Experience

International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 75 (2021) 101683 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Law and Psychiatry journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijlawpsy Challenges for people with intellectual disabilities in law enforcement interactions in Ireland; thematic analysis informed by 1537 person-years’ experience Gautam Gulati a,b,*, Alan Cusack a, John Bogue c, Anne O’Connor c, Valerie Murphy d, Darius Whelan e, Walter Cullen f, Cliona McGovern g, Brendan D. Kelly h, Elizabeth Fistein i, Shane Kilcommins a, Colum P. Dunne b a School of Law, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland b School of Medicine, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland c School of Psychology, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland d Department of Psychiatry, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland e School of Law, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland f Department of Primary Care, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland g Forensic & Legal Medicine, University College Dublin, Ireland h Department of Psychiatry, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland i School of Public Health and Primary Care, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Background: People with intellectual disabilities (PWID) are over-represented in criminal justice systems globally. Intellectual disabilities This over-representation reveals itself at once in the demographic make-up of prison populations, as well as those Police detained in police settings as suspects of crime. While it is well-established in international -

Iacp New Members

44 Canal Center Plaza, Suite 200 | Alexandria, VA 22314, USA | 703.836.6767 or 1.800.THEIACP | www.theIACP.org IACP NEW MEMBERS New member applications are published pursuant to the provisions of the IACP Constitution. If any active member in good standing objects to an applicant, written notice of the objection must be submitted to the Executive Director within 60 days of publication. The full membership listing can be found in the online member directory under the Participate tab of the IACP website. Associate members are indicated with an asterisk (*). All other listings are active members. Published May 1, 2020. Armenia Yezevan Ghambaryan, Artashes, Captain of Customs Service, State Revenue Committee of the Republic of Armenia Australia Victoria Docklands *West, Alexandra, Chief Psychologist, Victoria Police Service Bahrain Manama Al Marwani, Abdulla, Captain, Ministry of Interior Bangladesh Malibagh Dhaka Talukder, Mohammad Mahmudal Islam, Additional Superintendent, Criminal Investigation Department, Bangladesh Police Botswana Private Ba Gaborone Ndlovu, Christopher Busani, Assistant Commissioner of Police, Botswana Police Service Cambodia Phnom Penh Sokheang, Teang, Police Major General, General Dept of Immigration Canada British Columbia Vancouver *Prox, Ryan, S/Constable in Charge-Crime Analytics Advisory & Development Unit, Vancouver Police Dept Wrathall, Kris T, Inspector, Vancouver Police Dept Manitoba Winnipeg *Kumar, Ajit, Secretary, International Police Sports Council Ontario Chatham *Flikweert, Joshua, Constable, Chatham-Kent -

Centralized and Decentralized Police Systems: a Cross-National Mixed-Methods Study of the Effects of Policing Structures with Le

CENTRALIZED AND DECENTRALIZED POLICE SYSTEMS: A CROSS-NATIONAL MIXED-METHODS STUDY OF THE EFFECTS OF POLICING STRUCTURES WITH LESSONS FOR THAILAND _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by GRICHAWAT LOWATCHARIN Dr. Judith I. Stallmann, Dissertation Supervisor May, 2016 © Copyright by Grichawat Lowatcharin 2016 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled CENTRALIZED AND DECENTRALIZED POLICE SYSTEMS: A CROSS-NATIONAL MIXED-METHODS STUDY OF THE EFFECTS OF POLICING STRUCTURES WITH LESSONS FOR THAILAND presented by Grichawat Lowatcharin, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _______________________________________ Professor Judith I. Stallmann _______________________________________ Professor Anna Ball _______________________________________ Professor Charles E. Menifield _______________________________________ Associate Professor Emeritus Charles L. Sampson ï To the Lowatcharins and the Kongudoms úÐû ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my immeasurable appreciation and deepest gratitude to the following individuals, who have given me intellectual, emotional, morale, and/or spiritual supports over the course of my dissertation process and PhD career. First and foremost, Dr. Judy Stallmann, my major advisor. Although Star Wars is not her favorite movie, I could not think of her in any other way but her being a Jedi Master—the Yoda to my Luke Skywalker. Over the past few years, she has given me invaluable lessons in the ways of the Force and trained me to become a Jedi who is able to roam the intellectual universe not so far away. -

List of Competent Authorities Notified to the Commission In

12.2.2019 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 56/1 IV (Notices) NOTICES FROM MEMBER STATES List of competent authorities notified to the Commission in accordance with Article 43 of Regulation (EU) No 603/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the establishment of ‘Eurodac’ for the comparison of fingerprints for the effective application of Regulation (EU) No 604/2013 establishing the criteria and mechanisms for determining the Member State responsible for examining an application for international protection lodged in one of the Member States by a third-country national or a stateless person and on requests for the comparison with Eurodac data by Member States' law enforcement authorities and Europol for law enforcement purposes, and amending Regulation (EU) No 1077/2011 establishing a European Agency for the operational management of large-scale IT systems in the area of freedom, security and justice (2019/C 56/01) BELGIUM National Access Point BELGIAN IMMIGRATION OFFICE Antwerpsesteenweg 59B 1000 Brussels BELGIUM Tel. + 32 2 793 91 50 Fax + 32 2 201 57 24 E-mail: [email protected] Designated Authorities THE FOLLOWING SERVICES OF THE BELGIAN INTEGRATED POLICE: POLICE 7446 – CG/CGI/SPOC/Permanence Rue Royale 202A 1000 Bruxelles Tel. + 32 2 644 86 41 E-mail: [email protected] POLICE 7583 – DGJ/DJO/Permanence Rue Royale 202A 1000 Bruxelles Tel. + 32 2 642 78 09 E-mail: [email protected] POLICE 6270 – DGA/DAO/Ops/Permanence Rue Royale 202A 1000 Bruxelles Tel. + 32 2 642 63 80 E-mail: [email protected] POLICE 6658 – DJO Rue Royale 202A 1000 Bruxelles Tel.