Affairs 1 the Twain Shall Meet’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Pakistanonedge.Pdf

Pakistan Project Report April 2013 Pakistan on the Edge Copyright © Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, 2013 Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, Delhi Cantt., New Delhi - 110 010 Tel. (91-11) 2671-7983 Fax.(91-11) 2615 4191 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idsa.in ISBN: 978-93-82512-02-8 First Published: April 2013 Cover shows Data Ganj Baksh, popularly known as Data Durbar, a Sufi shrine in Lahore. It is the tomb of Syed Abul Hassan Bin Usman Bin Ali Al-Hajweri. The shrine was attacked by radical elements in July 2010. The photograph was taken in August 2010. Courtesy: Smruti S Pattanaik. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this Report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute or the Government of India. Published by: Magnum Books Pvt Ltd Registered Office: C-27-B, Gangotri Enclave Alaknanda, New Delhi-110 019 Tel.: +91-11-42143062, +91-9811097054 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.magnumbooks.org All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA). Contents Preface 5 Abbreviations 7 Introduction 9 Chapter 1 Political Scenario: The Emerging Trends Amit Julka, Ashok K. Behuria and Sushant Sareen 13 Chapter 2 Provinces: A Strained Federation Sushant Sareen and Ashok K. Behuria 29 Chapter 3 Militant Groups in Pakistan: New Coalition, Old Politics Amit Julka and Shamshad Ahmad Khan 41 Chapter 4 Continuing Religious Radicalism and Ever Widening Sectarian Divide P. -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Crisis Response Bulletin V3I1.Pdf

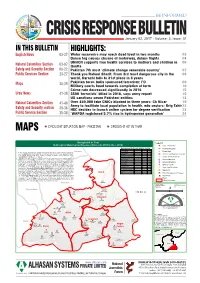

IDP IDP IDP CRISIS RESPONSE BULLETIN January 02, 2017 - Volume: 3, Issue: 01 IN THIS BULLETIN HIGHLIGHTS: English News 03-27 Water reservoirs may reach dead level in two months 03 Dense fog causes closure of motorway, delays flights 04 UNHCR supports free health services to mothers and children in 06 Natural Calamities Section 03-07 Quetta Safety and Security Section 08-22 Pakistan 7th most ‘climate change venerable country’ 07 Public Services Section 23-27 Thank you Raheel Sharif: From 3rd most dangerous city in the 08 world, Karachi falls to 31st place in 3 years Maps 28-29 Pakistan faces India sponsored terrorism: FO 09 Military courts head towards completion of term 10 Crime rate decreased significantly in 2016 15 Urdu News 41-30 3500 ‘terrorists’ killed in 2016, says army report 15 US sanctions seven Pakistani entities 18 Natural Calamities Section 41-40 Over 450,000 fake CNICs blocked in three years: Ch Nisar 19 Army to facilitate local population in health, edu sectors: Brig Tahir23 Safety and Security section 39-36 HEC decides to launch online system for degree verification 23 Public Service Section 35-30 ‘WAPDA registered 5.7% rise in hydropower generation’ 24 MAPS DROUGHT SITUATION MAP - PAKISTAN DROUGHT HIT IN THAR Drought Hit in Thar Legend Outbreak of Waterborne Diseases (from Jan,2016 to Dec, 2016) G Basic Health Unit Government & Private Health Facility ÷Ó Children Hospital Health Facility Government Private Total Sanghar Basic Health Unit 21 0 21 G Dispensary At least nine more infants died due to malnutrition and outbreak of the various diseases in Thar during that last two Children Hospital 0 1 1 days, raising the toll to 476 this year.With the death of nine more children the toll rose to 476 during past 12 months Dispensary 12 0 12 "' District Headquarter Hospital of the outgoing year, said health officials. -

The Battle for Pakistan

ebooksall.com ebooksall.com ebooksall.com SHUJA NAWAZ THE BATTLE F OR PAKISTAN The Bitter US Friendship and a Tough Neighbourhood PENGUIN BOOKS ebooksall.com Contents Important Milestones 2007–19 Abbreviations and Acronyms Preface: Salvaging a Misalliance 1. The Revenge of Democracy? 2. Friends or Frenemies? 3. 2011: A Most Horrible Year! 4. From Tora Bora to Pathan Gali 5. Internal Battles 6. Salala: Anatomy of a Failed Alliance 7. Mismanaging the Civil–Military Relationship 8. US Aid: Leverage or a Trap? 9. Mil-to-Mil Relations: Do More 10. Standing in the Right Corner 11. Transforming the Pakistan Army 12. Pakistan’s Military Dilemma 13. Choices Footnotes Important Milestones 2007–19 Preface: Salvaging a Misalliance 1. The Revenge of Democracy? 2. Friends or Frenemies? 3. 2011: A Most Horrible Year! 4. From Tora Bora to Pathan Gali 5. Internal Battles 6. Salala: Anatomy of a Failed Alliance 7. Mismanaging the Civil–Military Relationship 8. US Aid: Leverage or a Trap? 9. Mil-to-Mil Relations: Do More 10. Standing in the Right Corner 11. Transforming the Pakistan Army 12. Pakistan’s Military Dilemma 13. Choices Select Bibliography ebooksall.com Acknowledgements Follow Penguin Copyright ebooksall.com Advance Praise for the Book ‘An intriguing, comprehensive and compassionate analysis of the dysfunctional relationship between the United States and Pakistan by the premier expert on the Pakistan Army. Shuja Nawaz exposes the misconceptions and contradictions on both sides of one of the most crucial bilateral relations in the world’ —BRUCE RIEDEL, senior fellow and director of the Brookings Intelligence Project, and author of Deadly Embrace: Pakistan, America and the Future of the Global Jihad ‘A superb, thoroughly researched account of the complex dynamics that have defined the internal and external realities of Pakistan over the past dozen years. -

Play an Existing Slideshow 1 Select Pictures & Videos > Slideshows , Then Click on the Slideshow

urg_00874.book Page 46 Wednesday, July 16, 2008 9:03 AM Using the HD player 4 You can: ■ Click Play in the Slideshow tray to play the slideshow now (the tray must have 2 or more pictures). To exit the slideshow, click the Back button on the pointer remote. ■ Click Add to Slideshow again or the in the Slideshow tray to close it and play it later. Select Pictures & Videos > Slideshows to access the slideshow. ■ Click the New Slideshow button to clear the current Slideshow tray and begin a new slideshow. ■ Click the pictures in the Slideshow tray to go to Slideshow View and see larger thumbnails. To continue working with your slideshow, click the Actions button . See page 49 for details on Actions panels, and page 51 for Editing an existing slideshow. Play an existing slideshow 1 Select Pictures & Videos > Slideshows , then click on the slideshow. 2 Click any picture to open the slideshow. 3 Click Play in the slideshow controls. The slideshow begins with the picture you clicked. 46 www.kodak.com/go/easysharecenter urg_00874.book Page 47 Wednesday, July 16, 2008 9:03 AM Using the HD player Enjoying a Picture Chronicles slideshow Once a week, EASYSHARE Digital Display Software automatically creates a slideshow called Picture Chronicles. A Picture Chronicles slideshow includes not only the pictures that were added to your shared folders during the past 7 days, but also any pictures taken during the same time period in any year. The most recent Picture Chronicles slideshow is: ■ Located in Pictures & Videos > Slideshows ■ Created every Sunday ■ Limited to 50 pictures/videos You can turn off the Picture Chronicles slideshow creation or change the day of the week that the slideshow is initiated in EASYSHARE Digital Display Software. -

UNITED STATES-PAKISTAN RELATIONS: Facing a Critical Juncture

MAY 2012 Report ISPU UNITED STATES-PAKISTAN RELATIONS: Facing a Critical Juncture Imtiaz Ali ISPU Fellow Institute for Social Policy and Understanding © 2012 Institute for Social Policy and Understanding. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding. The Institute for Social Policy and Understanding normally does not take institutional positions on public policy issues. The views presented here do not necessarily reflect the views of the institute, its staff, or trustees. MAY 2012 REPORT About The Author Imtiaz Ali ISPU Fellow ImtiaZ ali is a fellow at the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding. He is also an award- winning journalist from Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province (KP), where he worked for local and foreign media organizations such as the Washington Post, the BBC Pashto Service and London’s Daily Telegraph, and Pakistani newspapers The News, Dawn, and Khyber Mail. He has extensively written on Pakistani politics, security, militancy and the “war on terror” in Pakistan since 9/11, focusing on Pakistan’s FATA region along the Afghanistan border. His opinion pieces and research articles have appeared in various leading publications and research journals including Yale Global Online, Foreign Policy Magazine, CTC Sentinel of West Point and the Global Terrorism Monitor of the Jamestown Foundation. He has also worked with prominent American think tanks such as the United States Institute of Peace, the New America Foundation, Terror Free Tomorrow and Network 20/20, consulting and advising on Pakistani politics, society, governance, elections, social issues and media/communication. -

Educationinority Groups;*Professional Education; *Urban Education

DOCUMENTRESUME ED 059 686 HE 002s-852 , TITLE Proceedings of the Annual Meetingof the Western Association of Graduate Schools(11th, Las Vegas, Nevada, March 2-4, 1969). INSTITUTION Idaho State Univ., Pocatello. PUB DATE May 6\ ,1 NOTE. 82p. I EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Graduate Students;.*GraduateStudy; *Higher , Educationinority Groups;*Professional Education; *Urban Education A141`ACT This is the report of the1969 annual conference of the Western Association . of Graduate Schools. Thefirst general meeting held at theconfeFence presented 3'speechesby minority students from thearea graduate schbols. Discussed inthese addresses, were the problems confronting the Ame]rica-n Indian, MexicanAmerican, and black studentsas students in the schools. Thesecond general session of the conferencedealt with the question ofw1ether or npt the graduate school is,athreat to umiergraduate educaion. In/the 2 addresses piesented at this sessionit was established h.pt graduate education is not only nota threat, but that undergraduatbeducation has never been better.The'third session presentedaddresses that pointed out thepros, cons, and institutional barriersto urban action programs within thegraduate school. The fourthsession presented remarks concerning theprofessionalization of graduate education, and the fifth session dealt with the changingexpectations of graduate students. Thesixth and final sessionwas a business /meeting at whichnew officers Tre elected: and various maAe. (HS) resolutions - P 4 1 Proceedings esternAssociation of Graduate* Schools S. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALT EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN HE RO- Eleventh Annual Meeting DUCE0 EXACTLY AS RECEIVED F OM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION RIG - INATING IT, POINTS OF VIEW.014 OPIN- IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU- March 2=4, 1969 CATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

E-Manual COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

E15788 First Edition / November 2019 E-Manual COPYRIGHT INFORMATION No part of this manual, including the products and software described in it, may be reproduced, transmitted, transcribed, stored in a retrieval system, or translated into any language in any form or by any means, except documentation kept by the purchaser for backup purposes, without the express written permission of ASUSTeK COMPUTER INC. (“ASUS”). ASUS PROVIDES THIS MANUAL “AS IS” WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EITHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OR CONDITIONS OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. IN NO EVENT SHALL ASUS, ITS DIRECTORS, OFFICERS, EMPLOYEES OR AGENTS BE LIABLE FOR ANY INDIRECT, SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL, OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES (INCLUDING DAMAGES FOR LOSS OF PROFITS, LOSS OF BUSINESS, LOSS OF USE OR DATA, INTERRUPTION OF BUSINESS AND THE LIKE), EVEN IF ASUS HAS BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES ARISING FROM ANY DEFECT OR ERROR IN THIS MANUAL OR PRODUCT. Products and corporate names appearing in this manual may or may not be registered trademarks or copyrights of their respective companies, and are used only for identification or explanation and to the owners’ benefit, without intent to infringe. SPECIFICATIONS AND INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THIS MANUAL ARE FURNISHED FOR INFORMATIONAL USE ONLY, AND ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE AT ANY TIME WITHOUT NOTICE, AND SHOULD NOT BE CONSTRUED AS A COMMITMENT BY ASUS. ASUS ASSUMES NO RESPONSIBILITY OR LIABILITY FOR ANY ERRORS OR INACCURACIES THAT MAY APPEAR IN THIS MANUAL, INCLUDING THE PRODUCTS AND SOFTWARE DESCRIBED IN IT. Copyright © 2019 ASUSTeK COMPUTER INC. -

January Was a Momentous Event

EDITOR’S NOTE The last three months have been as significant as any in the recent history of our country. The year 2014 ended with the drawdown of US-NATO forces from Afghanistan with many opining that the ‘job’ was only half done or less. There are legitimate fears of instability in the region that could spill over to other parts of South Asia and Central Asia. India is naturally concerned that the situation does not take an ugly turn that will be of detriment to us. The internal and external pulls and pressures are many that encompass terrorism, trade, diplomacy and power politics. The situation merits continuous monitoring for some time to come. Some contingency planning will also be in order. The visit of President Obama in January was a momentous event. Apart from the fact that he was the first US president to be the chief guest at our Republic Day parade, the visit signalled that the strategic partnership was well on track. There was the very apparent bonhomie between the leaders of the two countries and the mutual understanding on a host of different issues, including the “vision document”, was clearly noted by our friends and possible adversaries. President Obama’s commitment to support our “Make in India” programme was very welcome and so was the desire for furtherance of the Defence Trade and Technology Initiative. However, the Americans, once again, were insistent on our signing the three “foundation pacts” viz the Logistics Support Agreement (LSA), Communication Interoperability and Security Memorandum Agreement (CISMOA) and Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement for Geo-spatial Cooperation (BECA). -

Newsletter #9

the American Institute of Pakistan Studies PSN AIPS Fall 2002 Volume V Issue 1 New Series No. 9 STUDIES OF PAKISTAN NEW HORIZONS IN PAKISTAN STUDIES BY NORTH AMERICAN SCHOLARS, 1947-1966 Over the past year the image of Pakistan for The following is the third in our series of lished anything on the subcontinent. The the general public has changed in ways we excerpts from Maureen Patterson’s un- Institute of Pacific Relations (IPR), on could not have predicted a year ago, and the published work on the history of Pakistan the other hand, while primarily focused disruption of AIPS programs has become long- Studies in the U.S. on East and Southeast Asia, had just term. A year on from nine eleven we have had after World War II expanded its western time to take stock. We are obliged to discon- A preliminary review of articles, books perimeter to include South Asia; for ex- tinue many of the programs we have been iden- and dissertations by North American ample, the IPR held its quadrennial inter- tified with. We must take advantage of this scholars in the early period of Pakistan national conference in 1950 in Lucknow unexpected shock to redefine our field and de- studies from 1947 to the late sixties to (India), and then its thirteenth (and, as it velop programs that will perhaps lift it out of its the late demonstrates the scope and area turned out, its last) in Lahore (Pakistan) of scholarly concerns. While not exhaus- in 1958. The IPR’s Far Eastern Survey historical isolation and give Pakistan a more tive, the following lists of articles, books included articles on South Asia in the visible place in the curriculum, in the humani- and dissertations – arranged in chrono- early fifties, with a few on Pakistan as ties and the social sciences in general. -

Pakistan Security Report 2018

Conflict and Peace Studies VOLUME 11 Jan - June 2019 NUMBER 1 PAKISTAN SECURITY REPORT 2018 PAK INSTITUTE FOR PEACE STUDIES (PIPS) A PIPS Research Journal Conflict and Peace Studies Copyright © PIPS 2019 All Rights Reserved No part of this journal may be reproduced in any form by photocopying or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage or retrieval systems, without prior permission in writing from the publisher of this journal. Editorial Advisory Board Khaled Ahmed Dr. Catarina Kinnvall Consulting Editor, Department of Political Science, The Friday Times, Lahore, Pakistan. Lund University, Sweden. Prof. Dr. Saeed Shafqat Dr. Adam Dolnik Director, Centre for Public Policy and Governance, Professor of Counterterrorism, George C. Forman Christian College, Lahore, Pakistan. Marshall European Center for Security Studies, Germany. Marco Mezzera Tahir Abbas Senior Adviser, Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Professor of Sociology, Fatih University, Centre / Norsk Ressurssenter for Fredsbygging, Istanbul, Turkey. Norway. Prof. Dr. Syed Farooq Hasnat Rasul Bakhsh Rais Pakistan Study Centre, University of the Punjab, Professor, Political Science, Lahore, Pakistan. Lahore University of Management Sciences Lahore, Pakistan. Anatol Lieven Dr. Tariq Rahman Professor, Department of War Studies, Dean, School of Education, Beaconhouse King's College, London, United Kingdom. National University, Lahore, Pakistan. Peter Bergen Senior Fellow, New American Foundation, Washington D.C., USA. Pak Institute for Peace ISSN 2072-0408 ISBN 978-969-9370-32-8 Studies Price: Rs 1000.00 (PIPS) US$ 25.00 Post Box No. 2110, The views expressed are the authors' Islamabad, Pakistan own and do not necessarily reflect any +92-51-8359475-6 positions held by the institute.