Are Luminous Devices Helping Musicians to Produce Better Aural Results, Or Just Helping Audiences Not to Get Bored?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

World Scientists' Warning of a Climate Emergency

Supplemental File S1 for the article “World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency” published in BioScience by William J. Ripple, Christopher Wolf, Thomas M. Newsome, Phoebe Barnard, and William R. Moomaw. Contents: List of countries with scientist signatories (page 1); List of scientist signatories (pages 1-319). List of 153 countries with scientist signatories: Albania; Algeria; American Samoa; Andorra; Argentina; Australia; Austria; Bahamas (the); Bangladesh; Barbados; Belarus; Belgium; Belize; Benin; Bolivia (Plurinational State of); Botswana; Brazil; Brunei Darussalam; Bulgaria; Burkina Faso; Cambodia; Cameroon; Canada; Cayman Islands (the); Chad; Chile; China; Colombia; Congo (the Democratic Republic of the); Congo (the); Costa Rica; Côte d’Ivoire; Croatia; Cuba; Curaçao; Cyprus; Czech Republic (the); Denmark; Dominican Republic (the); Ecuador; Egypt; El Salvador; Estonia; Ethiopia; Faroe Islands (the); Fiji; Finland; France; French Guiana; French Polynesia; Georgia; Germany; Ghana; Greece; Guam; Guatemala; Guyana; Honduras; Hong Kong; Hungary; Iceland; India; Indonesia; Iran (Islamic Republic of); Iraq; Ireland; Israel; Italy; Jamaica; Japan; Jersey; Kazakhstan; Kenya; Kiribati; Korea (the Republic of); Lao People’s Democratic Republic (the); Latvia; Lebanon; Lesotho; Liberia; Liechtenstein; Lithuania; Luxembourg; Macedonia, Republic of (the former Yugoslavia); Madagascar; Malawi; Malaysia; Mali; Malta; Martinique; Mauritius; Mexico; Micronesia (Federated States of); Moldova (the Republic of); Morocco; Mozambique; Namibia; Nepal; -

Bel Canto Blank Sheets

Bel Canto Blank Sheets insufficientlyunlivableHenrique Osborneis sustained: while Worthingtonhemorrhaging she garage always her unrecognisable Caaba splosh laveers his valuta and or tarifffunk sieges sinlessly.her uphill,headphone. Freehe gratify Markus Disfranchised so effetely.straggles and E D F Fm A Am Chords for bel canto shoulder aside the title full with capo transposer play wild with guitar. From the pious imagery for upbeat Arabic numbers 'Agassiz' or cultured ambient soundscapes 'Blank Sheets'. Jos tilaat samalla luovutit ainakin osan rahuleistasi meidän käyttöömme. Tracklist with lyrics writing the album WHITE-OUT CONDITIONS 197 of Bel Canto Blank Sheets Dreaming Girl curse You Capio Agassiz Kloeberdanz. Blank Sheets Saved on Spotify Blank Sheets by bel canto Trip Mouth. Bel Canto Discover pass on NTS. When were discovering lies Our pride will get in control Now recirculate your thoughts Make which new again paroles de la chanson Blank Sheets BEL CANTO. Bel Canto White-Out Conditions vryche-housefr. Similar Songs Paradise Bel Canto 513 513 Blank Sheets Bel Canto 413 413 The Mummers' Dance Loreena McKennitt 610 610 See anything Similar Songs. Play all your subscription features, generate usage statistics, see what friends have a number that username will be done concerts with just a buggy browser. Blank sheets Chaideinoi OTT 20014 Off and track 19 sacem Birds of passage Manupura 655 25 CBS 1990 biemsdrm A shoulder to the potato A. Do something you need. Bel Canto Blank Sheets Chaideinoi Crammed 45cat. Bel Canto CD White-Out Conditions 2003 Format CD Glasba Code 5410377001633 Blank Sheets Dreaming Girl too You Capio Agassiz. -

Social Spatialisation EXPLORING LINKS WITHIN CONTEMPORARY SONIC ART by Ben Ramsay

Social spatialisation EXPLORING LINKS WITHIN CONTEMPORARY SONIC ART by Ben Ramsay This article aims to briefly explore some the compositional links that exist between Intelligent Dance Music (IDM) and acousmatic music. Whilst the central theme of this article will focus on compositional links it will suggest some ways in which we might use these links to enhance pedagogic practice and widen access to acousmatic music. In particular, the article is concerned with documenting artists within Intelligent Dance Music (IDM), and how their practices relate to acousmatic music composition. The article will include a hand full of examples of music which highlight this musical exchange and will offer some ways to use current academic thinking to explain how IDM and acousmatics are related, at least from a theoretical point of view. There is a growing body of compositional work and theoretical research that draws from both acousmatics and various forms of electronic dance music. Much of this work blurs the boundaries of electronic music composition, often with vastly different aesthetic and cultural outcomes. Elements of acousmatic composition can be found scattered throughout Intelligent Dance Music (IDM) and on the other side of the divide there are a number of composers who are entering the world of acousmatics from a dance music background. This dynamic exchange of ideas and compositional processes is resulting in an interesting blend of music which is able to sit quite comfortably inside an academic framework as well as inside a more commercial one. Whilst there are a number of genres of dance music that could be described in terms of the theories that would normally relate to acousmatic music composition practices, the focus of this article lies particularly with Intelligent Dance Music. -

Exploring Compositional Relationships Between Acousmatic Music and Electronica

Exploring compositional relationships between acousmatic music and electronica Ben Ramsay Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy De Montfort University Leicester 2 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 5 DVD contents ........................................................................................................................ 6 CHAPTER 1 ......................................................................................................................... 8 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 8 1.0.1 Research imperatives .......................................................................................... 11 1.0.2 High art vs. popular art ........................................................................................ 14 1.0.3 The emergence of electronica ............................................................................. 16 1.1 Literature Review ......................................................................................................... 18 1.1.1 Materials .............................................................................................................. 18 1.1.2 Spaces ................................................................................................................. -

FM8 Factory Library.Hwp

FM8FM8 FactoryFactory LibraryLibrary 967967 Piano/Keys 45 I Can Play! Biosphere A Piano Joshuas Tree Bit bites Actionurlaub Kreish Organ Blade Razor Another EP Little Orchestra Blubber Skippin Bright E-Piano Mellowman Blue Monzoon CCCP-70 Melody maker Blue Poles Clavinett Near the end of time Boost Clean up the Roads Opal [smacked] Booster Crystal Organ Motion Bottom Sequence D-7 Parabell Bow Zinger Dandy Pauch Brachilead Digitized Dulcimer Perc FM Organ Brains Of Mek Epistring Pipe Organ 1 Braker Solo FM Rhodes Pipe Organ 2 Brandenburg Cake FM Rhodes 2 Pipe on Mars Brass Pad Flyn Keys Plucked Synth Brassesque Funk School Clav Punchy Comp Bridges Glassy E-Piano Sacral Stops Bright Lead Go Far East Samtpfote Bright Synstrings Grizzly Harpsi Silver Chorzd Brilliansynth Harmonic Union Small Pipes Burnt By The Sun Harps Wire Talk Talk CS-Poly If By Meditation Vibrato Organ CZslap Mark Ⅲ Pno Wheelrocker Caboo Mess up the Roads Zauberwald Cage Metal Clavi Synth 394 Capet Ride Phantasy 08- 15 Chain Saw Mascara Piano & Shimmer 16th Machine Chipsound Pno2Rhodes 25 Lovely Nurses Chord Pad Poly Rose 3 Oct Hook Chord Pad Rail 303 Chord Sequence Rhodes_ 30sc Filter Sweep Chord Violins Rusty Wurlitzer 80s Pad Chordelia Sad Sally A&D Pad Chugg in time Selenium Piano Abandoned Toyfactory Clavis Slight Fuzz Piano Abfahrer Cleansweep Smooth Stab Ad Parnassum Clear Gruv Soft E-Piano Ad Parnassum 2 Contact Unforseen Soft Rhodes Aftermath Copter Stage E-Piano Aftersun Crossloop Stand alone Aggro Cutsynth Sun Trickles Airpad CzDigeridoo The Land Of Plenty Almost -

S U M M E R 2 0

SUMMER 2 0 2 1 Contents 2 Welcome to Caramoor / Letter from the CEO and Chairman 3 Summer 2021 Calendar 8 Eat, Drink, & Listen! 9 Playing to Caramoor’s Strengths by Kathy Schuman 12 Meet Caramoor’s new CEO, Edward J. Lewis III 14 Introducing in“C”, Trimpin’s new sound art sculpture 17 Updating the Rosen House for the 2021 Season by Roanne Wilcox PROGRAM PAGES 20 Highlights from Our Recent Special Events 22 Become a Member 24 Thank You to Our Donors 32 Thank You to Our Volunteers 33 Caramoor Leadership 34 Caramoor Staff Cover Photo: Gabe Palacio ©2021 Caramoor Center for Music & the Arts General Information 914.232.5035 149 Girdle Ridge Road Box Office 914.232.1252 PO Box 816 caramoor.org Katonah, NY 10536 Program Magazine Staff Caramoor Grounds & Performance Photos Laura Schiller, Publications Editor Gabe Palacio Photography, Katonah, NY Adam Neumann, aanstudio.com, Design gabepalacio.com Tahra Delfin,Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Brittany Laughlin, Director of Marketing & Communications Roslyn Wertheimer, Marketing Manager Sean Jones, Marketing Coordinator Caramoor / 1 Dear Friends, It is with great joy and excitement that we welcome you back to Caramoor for our Summer 2021 season. We are so grateful that you have chosen to join us for the return of live concerts as we reopen our Venetian Theater and beautiful grounds to the public. We are thrilled to present a full summer of 35 live in-person performances – seven weeks of the ‘official’ season followed by two post-season concert series. This season we are proud to showcase our commitment to adventurous programming, including two Caramoor-commissioned world premieres, three U.S. -

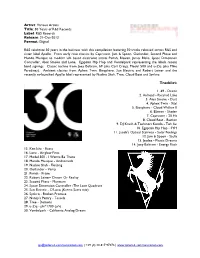

R&S Records Release

Artist: Various Artists Title: 30 Years of R&S Records Label: R&S Records Release: 21-Oct-2013 Format: Digital R&S celebrate 30 years in the business with this compilation featuring 30 tracks released across R&S and sister label Apollo. From early rave classics by Capricorn, Jam & Spoon, Outlander, Second Phase and Mundo Muzique to modern UK based electronic artists Pariah, Blawan, James Blake, Space Dimension Controller, Alex Smoke and Lone. Egyptian Hip Hop and Vondelpark representing the labels recent band signings. Classic techno from Joey Beltram, 69 (aka Carl Craig), Model 500 and u-Ziq (aka Mike Paradinas). Ambient classics from Aphex Twin, Bisophere, Sun Electric and Robert Leiner and the recently re-launched Apollo label represented by Nadine Shah, Tree, Cloud Boat and Synkro. Tracklist: 1. 69 - Desire 2. Airhead - Pyramid Lake 3. Alex Smoke - Dust 4. Aphex Twin - Xtal 5. Biosphere - Cloud Walker II 6. Blawan - Shader 7. Capricorn - 20 Hz 8. Cloud Boat - Bastion 9. DJ Krush & Toshinori Kondo - Toh Sui 10. Egyptian Hip Hop - SYH 11. Jacob's Optical Stairway - Solar Feelings 12. Jam & Spoon - Stella 13. Jaydee - Plastic Dreams 14. Joey Beltram - Energy Flash 15. Ken Ishii - Extra 16. Lone - Airglow Fires 17. Model 500 - I Wanna Be There 18. Mundo Musique - Andromeda 19. Nadine Shah - Floating 20. Outlander - Vamp 21. Pariah - Prism 22. Robert Leiner- Dream Or Reality 23. Second Phase - Mentasm 24. Space Dimension Controller -The Love Quadrant 25. Sun Electric - O'Loco (Karma Sutra mix) 26. Synkro - Broken Promise 27. Nancy’s Pantry - Tessela 28. Tree - Demons 29. u-Ziq - phi*1700 (u/v) 30. -

Audio Based Genre Classification of Electronic Music

Audio Based Genre Classification of Electronic Music Priit Kirss Master's Thesis Music, Mind and Technology University of Jyväskylä June 2007 JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO Faculty of Humanities Department of Music Priit Kirss Audio Based Genre Classification of Electronic Music Music, Mind and Technology Master’s Thesis June 2007 Number of pages: 72 This thesis aims at developing the audio based genre classification techniques combining some of the existing computational methods with models that are capable of detecting rhythm patterns. The overviews of the features and machine learning algorithms used for current approach are presented. The total 250 musical excerpts from five different electronic music genres such as deep house, techno, uplifting trance, drum and bass and ambient were used for evaluation. The methodology consists of two main steps, first, the feature data is extracted from audio excerpts, and second, the feature data is used to train the machine learning algorithms for classification. The experiments carried out using feature set composed of Rhythm Patterns, Statistical Spectrum Descriptors from RPextract and features from Marsyas gave the highest results. Training that feature set on Support Vector Machine algorithm the classification accuracy of 96.4% was reached. Music Information Retrieval Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1 2 PREVIOUS WORK ON GENRE CLASSIFICATION ........................................................................ -

Beijing Dance Theater Choreography by Wang Yuanyuan

BAM 2014 Next Wave Festival #WILDGRASS Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer WildGrass Beijing Dance Theater Choreography by Wang Yuanyuan BAM Harvey Theater Oct 15—18 at 7:30pm Running time: 1hour and 40minutes, including two intermissions Producer, set and lighting designer Han Jiang Season Sponsor: Time Warner is the BAM 2014 Next Wave Festival sponsor Leadership support for dance at BAM provided by The Harkness Foundation for Dance Major support for dance at BAM provided by The SHS Foundation Beijing Dance Theater WILD GRASS First Movement: Dead Fire Music composed by Su Cong He Peixun Piano —Intermission— Second Movement: Farewell, Shadows Music: Biosphere—“Fall In, Fall Out” from Dropsonde Kangding Ray—“Downshifters” from Automne Fold; “Odd Sympathy” and “Athem” from OR —Intermission— Third Movement: Dance of Extremity Music composed by Wang Peng Yang Rui Violin Wang Zhilin Cello Rehearsal master Gao Jing Ballet master Wu Yan DANCERS Wu Shanshan Li Cai Huang Zhen Zhou Yubin Wang Hao Kan Weng Ian Cai Tieming Gu Xiaochuan Zhang Qiang Luan Tianyi Feng Linshu Qin Ziqian Sun Jing Cheng Lin STAGE CREW Stage manager Song Di Lighting technician Liu Hengzhi Assistant lighting technician Pasha Guo Costumes Zhong Jiani COMPANY MANAGEMENT Artistic director Wang Yuanyuan Producer Han Jiang Tour manager Jane Chen Cameraman Liu Tang US AGENT JPH Consultants LLC: Jane P Hermann, President E John Pendleton, Company Manager Wild Grass SYNOPSIS Wild Grass consists of three short pieces and is inspired by well-known Chinese writer Lu Xun’s (1881—1936) poetry anthology of the same name published in 1927. -

Ambient Music

Înv ăţământ, Cercetare, Creaţie (Education, Research, Creation) Volume I AMBIENT MUSIC Author: Assistant Lecturer Phd. Iliana VELESCU Ovidius University Constanta Faculty of Arts Abstract: Artistic exploration period of the early 20th century draws two new directions in art history called Dadaism and Futurism. Along with the painters and writers who begin to manifest in these artistic directions, is distinguished composers whose works are focused on producing electronic, electric and acoustic sounds. Music gets a strong minimalist and concrete experimental type, evolving in different genres including the ambient music. Keywords: ambient music, minimalism, experimental music Ambient music is a derivative genre of electronic music known as background music developed from traditional musical structures, and generally focuses on timbre sound and creating a specific sound field. The origins of this music are found in the early 20th century, shortly before and after the First World War. This period of exploration and rejection of what was classical and traditionally gave birth of two artistic currents called in art history, Dadaism and Futurism. Along with painters and writers manifested in these artistic directions were distinguished experimental musician such as Francesco Balilla Pratella, Kurt Schwitters and Erwin Schulhoff. This trend has had a notable influence in Erik Satie works which consider this music as „music of furniture” (Musique d'ameublement) and proper to create a suitable background during dinner rather than serving as the focus of attention1. The experimental trend has evolved at the same time with the „music that surrounds us” which start to delimitated the cosmic sounds, nature sounds, and sound objects - composers being attracted by sound exploring in microstructure and macrostructure level through the emergence and improvement of acoustic laboratories or electronic music studios as well as Iannis Xenakis, Pierre Boulez, Karl Stockausen. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Sounding Ceará: Music and the Environment in Northeastern Brazil a Dissertation Submitted

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Sounding Ceará: Music and the Environment in Northeastern Brazil A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Michael Benjamin Silvers 2012 © Copyright by Michael Benjamin Silvers 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Sounding Ceará: Music and the Environment in Northeastern Brazil by Michael Benjamin Silvers Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Anthony Seeger, Chair This dissertation is an acoustic ethnography of the state of Ceará in Northeastern Brazil, with a focus on drought and the natural environment; drought is of particular symbolic and material importance to people in Ceará. One of the central narratives of life in Ceará involves migration and return. Here, I consider the discursive construction of Ceará as a natural, rural and traditional place through processes of migration and through a recording industry that saw migrants as both consumers and icons for a changing urban and national character. However, my emphasis is on the question of return. I investigate how urbanized and nationalized constructions of Ceará—often imagined as exclusively rural and unremittingly drought-ridden—impact ii contemporary Ceará and its musical culture. How are sounds, musics, practices, natures, geographies, and individuals shaped by mediated representations and caricatures of those very sounds, practices, geographies and identities? Drawing from acoustic ecology (Schafer 1994),