Zingiberaceae Extracts for Pain: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Shaheen E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Book Chefs Guide to Herbs and Spices

CHEFS GUIDE TO HERBS AND SPICES: REFERENCE GUIDE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Inc. Barcharts | 4 pages | 23 Feb 2006 | Barcharts, Inc | 9781423201823 | English | Boca Raton, FL, United States Chefs Guide to Herbs and Spices: Reference Guide PDF Book I also love it with lentils and in my chicken salad with apples. Cinnamon is beloved in both sweet and savory dishes around the world and can be used whole as sticks or ground. Email Required. They do tend to go stale and are not as pure as fresh ones so make sure they are green and strongly aromatic when you crush them. Read more about garlic here. Ginger powder is the dried and ground root of the flowering tropical plant Zingiber officinale, and has a milder and slightly sweeter taste than that of fresh ginger root. I never use parsley in dried form. Shred it and add it to a white sauce with mustard. From European mountains , but also moorland and heaths. Shrimp Alfredo is exquisite — juicy shrimp in a cheese sauce serves with pasta. It is widely used in Indian cuisine and is woody and pungent. The results is a lovely, sweetly smoky and lightly spiced flavor often found in spicy sausages like chorizo or salami, and paella. They also last for a long time in the fridge. Anise is the dried seed of an aromatic flowering plant, Pimpinella anisum , in the Apiaceae family that is native to the Levant, or eastern Mediterranean region, and into Southwest Asia. Cinnamon has a subtle, sweet, and complex flavor with floral and clove notes. -

RHS the Plantsman, December 2014

RubRic To come Zingiber mioga and its cultivars In temperate gardens Zingiber mioga is a good companion for other exotic-looking plants As hardy as the eaps of myoga in a Wild distribution Japanese supermarket The native range of Z. mioga extends hardiest roscoeas, in Hawai’i sparked our from central and southeast China to this edible ginger Hinterest in Zingiber mioga. Orchid- the mountains of north Vietnam and like flowers and a tropical appearance into South Korea. It is also found in also has desirable belie its hardiness. As well as being a Japan, but not Hokkaido. Colonies, ornamental qualities. popular culinary herb in the Far East, favouring rich, moist, well-drained Japanese ginger grows well in soils, usually grow on shady slopes Theodor Ch Cole temperate gardens. and in mountain valleys in the and Sven In this article we hope to understory of deciduous and mixed demonstrate what a good garden forests. The species probably nürnberger look plant it is, and highlight some of the originated in southeast China. at its many aspects ornamental cultivars. Knowledgeable gardeners in Europe and North Plant description and discuss its garden America are aware of this plant, Zingiber mioga is a rhizomatous use and cultivars but its potential is still greatly perennial with short vegetative underestimated in the West. shoots. The pseudostems are formed As well as being called myoga mostly by the leaf sheaths and the in Japan, it is known as rang he in alternate leaves are lanceolate. The China and yang ha in Korea. inflorescences, borne on a short 226 December 2014 PlantsmanThe Theodor CH Cole Theodor Questing rhizomes (above) show how the plant spreads to form dense colonies. -

Therapeutic Effects of Bossenbergia Rotunda

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2015): 78.96 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Therapeutic Effects of Bossenbergia rotunda S. Aishwarya Bachelor of Dental Surgery, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals Abstract: Boesenbergia rotunda (L.) (Fingerroot), formerly known as Boesenbergia or Kaempferiapandurata (Roxb). Schltr. (Zingiberaceae), is distributed in south-east Asian countries, such as Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. The rhizomes of this plant have been used for the treatment of peptic ulcer, as well as colic, oral diseases, urinary disorders, dysentery and inflammation. As people have started to focus more on natural plants species for their curative properties. B. rotunda is a native ingredient in many Asian countries and is used as a condiment in food. It is also used as traditional medicine to treat several illnesses, consumed as traditional tonic especially after childbirth, beauty aid for teenage girls, and as a leukorrhea preventive remedy for women. Its fresh rhizomes are also used to treat inflammatory diseases, in addition to being used as an antifungal, antiparasitic, and aphrodisiac among Thai folks. Moreover, AIDS patients self-medicate themselves with B. rotunda to cure the infection. With the advancement in technology, the ethnomedicinal usages of herbal plants can be explained through in vitro and in vivo studies to prove the activities of the plant extracts. The current state of research on B. rotunda clearly shows that the isolated bioactive compounds have high potential in treating many diseases. Keywords: Zingerberaceae, anti fungal, anti parasitic, Chalcones, flavonoids. 1. Introduction panduratin derivative are prenylated flavonoids from B. pandurata that showed broad range of biological activities, Boesenbergia rotunda is a ginger species that grows in such as strong antibacterial acitivity9-11, anti- inflammatory Southeast Asia, India, Sri Lanka, and Southern China. -

Micropropagation-An in Vitro Technique for the Conservation of Alpinia Galanga

Available online a t www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library Advances in Applied Science Research, 2014, 5(3):259-263 ISSN: 0976-8610 CODEN (USA): AASRFC Micropropagation-an in vitro technique for the conservation of Alpinia galanga Nongmaithem M. Singh 1, Lukram A. Chanu 1, Yendrembam P. Devi 1, Wahengbam R.C. Singh 2 and Heigrujam B. Singh 2 1DBT-Institutional Biotech Hub, Pettigrew College, Ukhrul, Manipur 2DBT- Institutional Biotech Hub, Deptt. of Biotechnology, S.K. Women’s College, Nambol, Manipur _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT This study was conducted to develop an efficient protocol for mass propagation of Alpinia galanga L. Explants from rhizome buds were cultured on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium supplemented with 6-Benzylaminopurine (BAP) alone (0 to 5 mg/l) or a combination of BAP (0 to 5 mg/l) and indole 3-acetic acid (IAA) (0 to 2 mg/l). MS medium supplemented with a combination of 5.0 mg/l BAP and 2.0 mg/l IAA or 3.0 mg/l BAP and 0.5 mg/l IAA produced the highest mean number of shoots per explant as compared to other concentrations. The best shoot length was obtained on the medium containing 1.0 mg/l of BAP and 2.0 mg/l IAA. Thus, combined effects of BAP and IAA improved significantly the shoot growth and proliferation. MS medium supplemented with a combination of 5.0 mg/l BAP and 2 mg/l IAA gave the highest number of roots. However, longest roots per explant were obtained with 1.0 mg/l BAP alone. -

Propagation of Zingiberaceae and Heliconiaceae1

14 Sociedade Brasileira de Floricultura e Plantas Ornamentais Propagation of Zingiberaceae and Heliconiaceae1 RICHARD A.CRILEY Department of Horticulture, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii USA 96822 Increased interest in tropical cut vegetative growths will produce plants flower export in developing nations has identical to the parent. A few lesser gen- increased the demand for clean planting era bear aerial bulbil-like structures in stock. The most popular items have been bract axils. various gingers (Alpinia, Curcuma, and Heliconia) . This paper reviews seed and Seed vegetative methods of propagation for Self-incompatibility has been re- each group. Auxins such as IBA and ported in Costus (WOOD, 1992), Alpinia NAA enhanced root development on aerial purpurata (HIRANO, 1991), and Zingiber offshoots of Alpinia at the rate 500 ppm zerumbet (IKEDA & T ANA BE, 1989); while while the cytokinin, PBA, enhanced ba- other gingers set seed readily. sal shoot development at 100 ppm. Rhi- zomes of Heliconia survived treatment in The seeds of Alpinia, Etlingera, and Hedychium are borne in round or elon- 4811 C hot water for periods up to 1 hour gated capsules which split when the seeds and 5011 C up to 30 minutes in an experi- are ripe and ready for dispersai. ln some ment to determine their tolerance to tem- species a fleshy aril, bright orange or scar- pera tures for eradicating nematodes. Iet in color, covers .the seed, perhaps to Pseudostems soaks in 400 mg/LN-6- make it more attractive to birds. The seeds benzylaminopurine improved basal bud of gingers are black, about 3 mm in length break on heliconia rhizomes. -

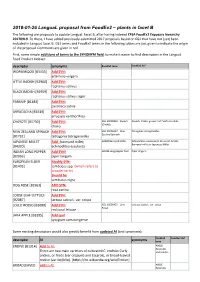

2018-01-26 Langual Proposal from Foodex2 – Plants in Facet B

2018-01-26 LanguaL proposal from FoodEx2 – plants in facet B The following are proposals to update LanguaL Facet B, after having indexed EFSA FoodEx2 Exposure hierarchy 20170919. To these, I have added previously-submitted 2017 proposals based on GS1 that have not (yet) been included in LanguaL facet B. GS1 terms and FoodEx2 terms in the following tables are just given to indicate the origin of the proposal. Comments are given in red. First, some simple additions of terms to the SYNONYM field, to make it easier to find descriptors in the LanguaL Food Product Indexer: descriptor synonyms FoodEx2 term FoodEx2 def WORMWOOD [B3433] Add SYN: artemisia vulgaris LITTLE RADISH [B2960] Add SYN: raphanus sativus BLACK RADISH [B2959] Add SYN: raphanus sativus niger PARSNIP [B1483] Add SYN: pastinaca sativa ARRACACHA [B3439] Add SYN: arracacia xanthorrhiza CHAYOTE [B1730] Add SYN: GS1 10006356 - Squash Squash, Choko, grown from Sechium edule (Choko) choko NEW ZEALAND SPINACH Add SYN: GS1 10006427 - New- Tetragonia tetragonoides Zealand Spinach [B1732] tetragonia tetragonoides JAPANESE MILLET Add : barnyard millet; A000Z Barnyard millet Echinochloa esculenta (A. Braun) H. Scholz, Barnyard millet or Japanese Millet. [B4320] echinochloa esculenta INDIAN LONG PEPPER Add SYN! A019B Long pepper fruit Piper longum [B2956] piper longum EUROPEAN ELDER Modify SYN: [B1403] sambucus spp. (which refers to broader term) Should be sambucus nigra DOG ROSE [B2961] ADD SYN: rosa canina LOOSE LEAF LETTUCE Add SYN: [B2087] lactusa sativa L. var. crispa LOLLO ROSSO [B2088] Add SYN: GS1 10006425 - Lollo Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa Rosso red coral lettuce JAVA APPLE [B3395] Add syn! syzygium samarangense Some existing descriptors would also greatly benefit from updated AI (and synonyms): FoodEx2 FoodEx2 def descriptor AI synonyms term ENDIVE [B1314] Add to AI: A00LD Escaroles There are two main varieties of cultivated C. -

Plant Life of Western Australia

INTRODUCTION The characteristic features of the vegetation of Australia I. General Physiography At present the animals and plants of Australia are isolated from the rest of the world, except by way of the Torres Straits to New Guinea and southeast Asia. Even here adverse climatic conditions restrict or make it impossible for migration. Over a long period this isolation has meant that even what was common to the floras of the southern Asiatic Archipelago and Australia has become restricted to small areas. This resulted in an ever increasing divergence. As a consequence, Australia is a true island continent, with its own peculiar flora and fauna. As in southern Africa, Australia is largely an extensive plateau, although at a lower elevation. As in Africa too, the plateau increases gradually in height towards the east, culminating in a high ridge from which the land then drops steeply to a narrow coastal plain crossed by short rivers. On the west coast the plateau is only 00-00 m in height but there is usually an abrupt descent to the narrow coastal region. The plateau drops towards the center, and the major rivers flow into this depression. Fed from the high eastern margin of the plateau, these rivers run through low rainfall areas to the sea. While the tropical northern region is characterized by a wet summer and dry win- ter, the actual amount of rain is determined by additional factors. On the mountainous east coast the rainfall is high, while it diminishes with surprising rapidity towards the interior. Thus in New South Wales, the yearly rainfall at the edge of the plateau and the adjacent coast often reaches over 100 cm. -

Thai Zingiberaceae : Species Diversity and Their Uses

URL: http://www.iupac.org/symposia/proceedings/phuket97/sirirugsa.html © 1999 IUPAC Thai Zingiberaceae : Species Diversity And Their Uses Puangpen Sirirugsa Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Prince of Songkla University, Hat Yai, Thailand Abstract: Zingiberaceae is one of the largest families of the plant kingdom. It is important natural resources that provide many useful products for food, spices, medicines, dyes, perfume and aesthetics to man. Zingiber officinale, for example, has been used for many years as spices and in traditional forms of medicine to treat a variety of diseases. Recently, scientific study has sought to reveal the bioactive compounds of the rhizome. It has been found to be effective in the treatment of thrombosis, sea sickness, migraine and rheumatism. GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE FAMILY ZINGIBERACEAE Perennial rhizomatous herbs. Leaves simple, distichous. Inflorescence terminal on the leafy shoot or on the lateral shoot. Flower delicate, ephemeral and highly modified. All parts of the plant aromatic. Fruit a capsule. HABITATS Species of the Zingiberaceae are the ground plants of the tropical forests. They mostly grow in damp and humid shady places. They are also found infrequently in secondary forest. Some species can fully expose to the sun, and grow on high elevation. DISTRIBUTION Zingiberaceae are distributed mostly in tropical and subtropical areas. The center of distribution is in SE Asia. The greatest concentration of genera and species is in the Malesian region (Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, the Philippines and Papua New Guinea) *Invited lecture presented at the International Conference on Biodiversity and Bioresources: Conservation and Utilization, 23–27 November 1997, Phuket, Thailand. -

Check List of Wild Angiosperms of Bhagwan Mahavir (Molem

Check List 9(2): 186–207, 2013 © 2013 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution Check List of Wild Angiosperms of Bhagwan Mahavir PECIES S OF Mandar Nilkanth Datar 1* and P. Lakshminarasimhan 2 ISTS L (Molem) National Park, Goa, India *1 CorrespondingAgharkar Research author Institute, E-mail: G. [email protected] G. Agarkar Road, Pune - 411 004. Maharashtra, India. 2 Central National Herbarium, Botanical Survey of India, P. O. Botanic Garden, Howrah - 711 103. West Bengal, India. Abstract: Bhagwan Mahavir (Molem) National Park, the only National park in Goa, was evaluated for it’s diversity of Angiosperms. A total number of 721 wild species belonging to 119 families were documented from this protected area of which 126 are endemics. A checklist of these species is provided here. Introduction in the National Park are Laterite and Deccan trap Basalt Protected areas are most important in many ways for (Naik, 1995). Soil in most places of the National Park area conservation of biodiversity. Worldwide there are 102,102 is laterite of high and low level type formed by natural Protected Areas covering 18.8 million km2 metamorphosis and degradation of undulation rocks. network of 660 Protected Areas including 99 National Minerals like bauxite, iron and manganese are obtained Parks, 514 Wildlife Sanctuaries, 43 Conservation. India Reserves has a from these soils. The general climate of the area is tropical and 4 Community Reserves covering a total of 158,373 km2 with high percentage of humidity throughout the year. -

Galangal from Laos to Inhibit Some Foodborne Pathogens, Particularly Escherichia Coli, Salmonella Enterica Serovar

Food and Applied Bioscience Journal, 2018, 6(Special Issue on Food and Applied Bioscience), 218–239 218 Antimicrobial Activities of some Herb and Spices Extracted by Hydrodistillation and Supercritical Fluid Extraction on the Growth of Escherichia coli, Salmonella Typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus in Microbiological Media Somhak Xainhiaxang1,2, Noppol Leksawasdi1 and Tri Indrarini Wirjantoro1,* Abstract This study investigated the antimicrobial actions of Zanthoxylum limonella, neem leaves, garlic and galangal from Laos to inhibit some foodborne pathogens, particularly Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica serovar. Typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus. Herb extracts were obtained by hydrodistillation at 100ºC for 4 h at atmospheric pressure or by supercritical fluid extraction at 45ºC and 17 MPa for 4 h. The antimicrobial activities of the extracts were then studied against three different pathogens on microbiological media using Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC), Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) and agar disc diffusion assay. The highest yield extract was determined in the Z. limonella extract obtained by hydrodistillation, which was 6.32±0.40%. In the MIC method, the Z. limonella extract from hydrodistillation and galangal extract obtained by supercritical fluid extraction at a concentration of 12.5% could inhibit all of the studied pathogens. However, it was only the Z. limonella extract produced by hydrodistillation that could kill the pathogens at the lowest concentration of 12.5%. Regarding the agar disc diffusion assay, Z. limonella extract from hydrodistillation at 100% concentration could inhibit E. coli for 15.67±1.81 mm, which was not significantly different to that of an antibiotic control of 10 g methicillin (p≥0.05). For S. -

Effect of Turmeric (Curcuma Longa Zingiberaceae) Extract Cream On

Zaman & Akhtar Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research October 2013; 12 (5): 665-669 ISSN: 1596-5996 (print); 1596-9827 (electronic) © Pharmacotherapy Group, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Benin, Benin City, 300001 Nigeria. All rights reserved . Available online at http://www.tjpr.org http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/tjpr.v12i5.1 Original Research Article Effect of Turmeric ( Curcuma longa Zingiberaceae) Extract Cream on Human Skin Sebum Secretion Shahiq uz Zaman* and Naveed Akhtar Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy and Alternative Medicine, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, 63100 Pakistan *For correspondence: Email: [email protected]; Tel: 0092-333-3854488 Received: 5 September 2012 Revised accepted: 15 July 2013 Abstract Purpose: To evaluate the effect of a w/o cream of turmeric (Curcuma longa Zingiberaceae) extract on skin sebum secretion in human volunteers. Methods: Two w/o cream formulations were prepared - one contained 5% extract prepared from the rhizomes of the plant, turmeric, and the second was similar except that it did not contain the extract and served as control. The antioxidant activity of the extract was determined by using the DPPH method. Evaluation of the effect of the creams on skin sebum secretion was conducted with the aid of a sebumeter. Initial sebum measurements on the face of thirteen human volunteers were taken with the sebumeter prior to application of cream, and then fortnightly after twice daily application of cream (on the right and left cheeks for control and extract creams, respectively) over a period of three months. Results : Significant increase (p ˂ 0.05) in the sebum values was observed from the 6 th week onwards after control cream application. -

A Review of the Literature

Pharmacogn J. 2019; 11(6)Suppl:1511-1525 A Multifaceted Journal in the field of Natural Products and Pharmacognosy Original Article www.phcogj.com Phytochemical and Pharmacological Support for the Traditional Uses of Zingiberacea Species in Suriname - A Review of the Literature Dennis RA Mans*, Meryll Djotaroeno, Priscilla Friperson, Jennifer Pawirodihardjo ABSTRACT The Zingiberacea or ginger family is a family of flowering plants comprising roughly 1,600 species of aromatic perennial herbs with creeping horizontal or tuberous rhizomes divided into about 50 genera. The Zingiberaceae are distributed throughout tropical Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Many members are economically important as spices, ornamentals, cosmetics, Dennis RA Mans*, Meryll traditional medicines, and/or ingredients of religious rituals. One of the most prominent Djotaroeno, Priscilla Friperson, characteristics of this plant family is the presence of essential oils in particularly the rhizomes Jennifer Pawirodihardjo but in some cases also the leaves and other parts of the plant. The essential oils are in general Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of made up of a variety of, among others, terpenoid and phenolic compounds with important Medical Sciences, Anton de Kom University of biological activities. The Republic of Suriname (South America) is well-known for its ethnic and Suriname, Paramaribo, SURINAME. cultural diversity as well as its extensive ethnopharmacological knowledge and unique plant Correspondence biodiversity. This paper first presents some general information on the Zingiberacea family, subsequently provides some background about Suriname and the Zingiberacea species in the Dennis RA Mans country, then extensively addresses the traditional uses of one representative of the seven Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Anton de Kom genera in the country and provides the phytochemical and pharmacological support for these University of Suriname, Kernkampweg 6, uses, and concludes with a critical appraisal of the medicinal values of these plants.