2007 Report, Prepared by Clallam County Noxious Weed Control Board

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Summary……………………………………………………...… 1

2009 Olympic Knotweed Working Group Knotweed in Sekiu, 2009 prepared by Clallam County Noxious Weed Control Board For more information contact: Clallam County Noxious Weed Control Board 223 East 4th Street Ste 15 Port Angeles WA 98362 360-417-2442 or [email protected] or http://clallam.wsu.edu/weeds.html CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……………………………………………………...… 1 OVERVIEW MAPS……………………………………………………………… 2 & 3 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 4 Project Goal……………………………………………………………………… 4 Project Overview………………………………………………………………… 4 2009 Overview…………………………………………………………………… 4 2009 Summary…………………………………………………………………... 5 2009 Project Procedures……………………………………………………….. 6 Outreach………………………………………………………………………….. 8 Funding……………………………………………………………………………. 8 Staff Hours………………………………………………………………………... 8 Participating Groups……………………………………………………………... 9 Observations and Conclusions…………………………………………………. 10 Recommendations……………………………………………………………..... 10 PROJECT ACTIVITIES BY WATERSHED Quillayute River System ………………………………………………………... 12 Big River and Hoko-Ozette Road………………………………………………. 15 Sekiu River………………………………………………………........................ 18 Hoko River………………………………………………………......................... 20 Sekiu, Clallam Bay and Highway 112…………………………………………. 22 Clallam River………………………………………………………..................... 24 Pysht River………………………………………………………........................ 26 Sol Duc River and tributaries…………………………………………………… 28 Forks………………………………………………………………………………. 34 Valley Creek……………………………………………………………………… 36 Peabody Creek…………………………………………………………………… 37 Ennis Creek………………………………………………………………………. -

Clallam County Community Wildfire Protection Plan

Clallam County Community Wildfire Protection Plan Clallam County Community Wildfire Protection Plan December 2009 Developed by Shea McDonald and Dwight Barry, Peninsula College Center of Excellence. Contributions and developmental assistance: Chris DeSisto, Tiffany Nabors, Erin Drake, and Aaron Lambert; Western Washington University-Peninsulas; Bill Sanders and Bryan Suslick, Washington Department of Natural Resources; Al Knobbs, Clallam County Fire District 3; Jon Bugher, Clallam County Fire District 2; Phil Arbeiter, Clallam County Fire District 1; Larry Nickey, Olympic National Park; Clea Rome, USDA-NRCS; and Dean Millett, US Forest Service. GIS analysis by Shea McDonald, Chris DeSisto, and Dwight Barry. Cartography by Shea McDonald. Project funded under Title III of the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000. 1 Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 6 Overview ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Policy Context ............................................................................................................................. 7 Healthy Forests Restoration Act ........................................................................................................... 7 National Fire Plan ................................................................................................................................. -

Case Studies of Three Salmon and Steelhead Stocks in Oregon and Washington, Including Population Status, Threats, and Monitoring Recommendations

HOW HEALTHY ARE HEALTHY STOCKS? Case Studies of Three Salmon and Steelhead Stocks in Oregon and Washington, including Population Status, Threats, and Monitoring Recommendations Prepared for the Native Fish Society April 2001 How Healthy Are Healthy Stocks? Case Studies of Three Salmon and Steelhead Stocks in Oregon and Washington, including Population Status, Threats, and Monitoring Recommendations Prepared for: Bill Bakke, Director Native Fish Society P.O. Box 19570 Portland, Oregon 97280 Prepared by: Peter Bahls, Senior Fish Biologist David Evans and Associates, Inc. 2828 S.W. Corbett Avenue Portland, Oregon 97201 Sponsored by the Native Fish Society and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. April 2001 Please cite this document as follows: Bahls, P. 2001. How healthy are healthy stocks? Case studies of three salmon and steelhead stocks in Oregon and Washington, including population status, threats, and monitoring recommendations. David Evans and Associates, Inc. Report. Portland, Oregon, USA. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Three salmon stocks were chosen for case studies in Oregon and Washington that were previously identified as “healthy” in a coast-wide assessment of stock status (Huntington et al. 1996): fall chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) of the Wilson River, summer steelhead (O. mykiss) of the Middle Fork John Day (MFJD) River, and winter steelhead (O. mykiss) of the Sol Duc River. The purpose of the study was to examine with a finer focus the status of these three stocks and the array of human influences that affect them. The best available information was used, some of which has become available since the 1996 assessment of healthy stocks was conducted. Recommendations for monitoring were developed to address priority data gaps and most pressing threats to the species. -

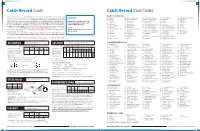

Catch Record Cards & Codes

Catch Record Cards Catch Record Card Codes The Catch Record Card is an important management tool for estimating the recreational catch of PUGET SOUND REGION sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness crab. A catch record card must be REMINDER! 824 Baker River 724 Dakota Creek (Whatcom Co.) 770 McAllister Creek (Thurston Co.) 814 Salt Creek (Clallam Co.) 874 Stillaguamish River, South Fork in your possession to fish for these species. Washington Administrative Code (WAC 220-56-175, WAC 825 Baker Lake 726 Deep Creek (Clallam Co.) 778 Minter Creek (Pierce/Kitsap Co.) 816 Samish River 832 Suiattle River 220-69-236) requires all kept sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness Return your Catch Record Cards 784 Berry Creek 728 Deschutes River 782 Morse Creek (Clallam Co.) 828 Sauk River 854 Sultan River crab to be recorded on your Catch Record Card, and requires all anglers to return their fish Catch by the date printed on the card 812 Big Quilcene River 732 Dewatto River 786 Nisqually River 818 Sekiu River 878 Tahuya River Record Card by April 30, or for Dungeness crab by the date indicated on the card, even if nothing “With or Without Catch” 748 Big Soos Creek 734 Dosewallips River 794 Nooksack River (below North Fork) 830 Skagit River 856 Tokul Creek is caught or you did not fish. Please use the instruction sheet issued with your card. Please return 708 Burley Creek (Kitsap Co.) 736 Duckabush River 790 Nooksack River, North Fork 834 Skokomish River (Mason Co.) 858 Tolt River Catch Record Cards to: WDFW CRC Unit, PO Box 43142, Olympia WA 98504-3142. -

Bogachiel Wild Steelhead Broodstock Program – Options Document August 19, 2014

Bogachiel Wild Steelhead Broodstock Program – Options Document August 19, 2014 Background The Washington Department of Game entered into a 25-year cooperative agreement with the Olympic Peninsula Guides’ Association (OPGA) on June 17, 1986. The purpose of the agreement was: “to provide a maximum of 100,000 winter steelhead smolts of wild Soleduck River stock annually for release into the Soleduck River. These fish shall be reared to release size (larger than 10 fish /pound) on OPGA managed facilities and are to be used to produce additional harvestable adult steelhead for commercial and sport fishermen on the Quillayute River system. Returning adults from this project will be considered hatchery fish for the purposes of harvest management.” The OPGA was to draw broodstock each year from early returning Sol Duc wild steelhead, to be collected prior to February 1. The early returning wild steelhead were targeted to provide additional harvestable steelhead during the period between the December peaking early-timed hatchery returns and the later wild returns. There was an additional assumption that returning Snider origin steelhead that escaped the fisheries would bolster the early portion of the wild return, which is typically subjected to higher exploitation rates than the later timed peak return of wild steelhead. This agreement expired June of 2011, prompting a review of the project to assess its performance in light of its original purpose and the more recently developed Hatchery and Fishery Reform Policy guidelines, and management directives contained in the Statewide Steelhead Management Plan. A written assessment of the performance of the program, completed spring of 2011, is available for download from the web at: http://wdfw.wa.gov/publications/01187/. -

North Pacific Coast (WRIA 20) Salmon Restoration Strategy (2021 Edition)

North Pacific Coast (WRIA 20) Salmon Restoration Strategy (2021 Edition) North Pacific Coast Lead Entity University of Washington, Olympic Natural Resources Center 1455 South Forks Avenue, P.O. Box 1628, Forks, WA 98331 Approved by the North Pacific Coast Lead Entity Public Review Draft - Pending April 2021 final approval 2021 North Pacific Coast (WRIA 20) Salmon Restoration Strategy Table of Contents Page - Table of Contents i - List of Figures ii - List of Tables ii - Acronyms iii - Glossary iv - Executive Summary xi - Acknowledgements xii Section 1: Project Prioritization and Application Processes 1.1 Goals and Objectives. 1 1.1.1 Incorporating Climate Change 2 1.1.2 Education and Outreach 3 1.2 Project Prioritization Method. 4 1.2.1 Descriptions of Prioritization Categories: 7 1.3 Review Process (Project application procedure, explanation of evaluation process). 10 1.4 Annual Project List. 10 1.5 Eligibility for the Annual Project Round 11 Section 2: Priority Projects by Geographic Section 2.0 All WRIA 20 Basins System-wide 12 2.1 Hoh River Basin: 2.1.1 Hoh Watershed Background. 13 2.1.2 Hoh River Watershed Priority Projects. 18 2.2 Quillayute River Complex: 2.2.1 Quillayute Basin Background. 21 2.1.1.1 Climate Change Forecasts 23 2.2.2 Quillayute Basin Prioritized Projects: 24 2.2.2.0 Quillayute Basin-Wide Priority Projects. 24 2.2.2.1 Quillayute Main Stem Priority Projects. 25 2.2.2.2 Dickey River Watershed Priority Projects. 27 2.2.2.3 Bogachiel River Watershed Priority Projects. 28 2.2.2.4 Calawah River Watershed Priority Projects. -

2016 State of Our Watersheds Report Quillayute River Basin Quileute Tribe

2016 State of Our Watersheds Report Quillayute River Basin abitat projects are vital to restoring the Hsalmon fishery. We have successfully partnered on projects in the past but we need many more into the future. - MEL MOON, NATURAL RESOURCES DIRECTOR QUILEUTE TRIBE Quileute Tribe The Quileute Tribe is located in La Push, on the shores of the Pacific Ocean, where tribal members have lived and hunted for thousands of years. Although their reservation is only about 2 square miles, the Tribe’s original territory stretched along the shores of the Pacific from the glaciers of Mount Olympus to the rivers of rain forests. Much has changed since those times, but Quileute elders remember the time when the Seattle people challenged Kwalla, the mighty whale. They also tell the story of how the bayak, or ra- ven, placed the sun in the sky. 178 Quileute Tribe Large Watershed Has Significant Subbasins The Quileute Tribe’s Area of Concern co-managed with the state of Washington, includes the northern portion of WRIA 20, and the Quileute Tribe has a shared Usual from Lake Ozette to the Goodman Creek and Accustomed area with the Makah Tribe Watershed. The largest basin in the area in the Lake Ozette basin. The Lake Ozette is the Quillayute, with four major sub-ba- sockeye is listed as threatened under the sins: the Dickey, Sol Duc, Calawah and Endangered Species Act. Bogachiel rivers. This part of the coastal The area is heavily forested with rela- region is a temperate rainforest with abun- tively infrequent impervious cover caused dant waterfall and an annual rainfall that by development and small population cen- can reach 140 inches. -

Adapting to Climate Change at Olympic National Forest and Olympic National Park

United States Department of Agriculture Adapting to Climate Forest Service Pacific Northwest Change at Olympic Research Station General Technical Report National Forest and PNW-GTR-844 August 2011 Olympic National Park The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the national forests and national grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Editors Jessica E. Halofsky is a research ecologist, University of Washington, College of the Environment, School of Forest Resources, Box 352100, Seattle, WA 98195-2100; David L. -

Wild Olympics Wilderness and Wild and Scenic Rivers Act

116TH CONGRESS REPORT " ! 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 116–388 WILD OLYMPICS WILDERNESS AND WILD AND SCENIC RIVERS ACT FEBRUARY 4, 2020.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. GRIJALVA, from the Committee on Natural Resources, submitted the following R E P O R T together with DISSENTING VIEWS [To accompany H.R. 2642] [Including cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office] The Committee on Natural Resources, to whom was referred the bill (H.R. 2642) to designate and expand wilderness areas in Olym- pic National Forest in the State of Washington, and to designate certain rivers in Olympic National Forest and Olympic National Park as wild and scenic rivers, and for other purposes, having con- sidered the same, report favorably thereon with an amendment and recommend that the bill as amended do pass. The amendment is as follows: Strike all after the enacting clause and insert the following: SEC. 1. SHORT TITLE. This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Wild Olympics Wilderness and Wild and Scenic Riv- ers Act’’. SEC. 2. DESIGNATION OF OLYMPIC NATIONAL FOREST WILDERNESS AREAS. (a) IN GENERAL.—In furtherance of the Wilderness Act (16 U.S.C. 1131 et seq.), the following Federal land in the Olympic National Forest in the State of Wash- ington comprising approximately 126,554 acres, as generally depicted on the map entitled ‘‘Proposed Wild Olympics Wilderness and Wild and Scenic Rivers Act’’ and dated April 8, 2019 (referred to in this section as the ‘‘map’’), is designated as wil- derness and as components of the National Wilderness Preservation System: (1) LOST CREEK WILDERNESS.—Certain Federal land managed by the Forest Service, comprising approximately 7,159 acres, as generally depicted on the map, which shall be known as the ‘‘Lost Creek Wilderness’’. -

Supplement of What's Streamflow Got to Do With

Supplement of Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 19, 1415–1431, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-19-1415-2019-supplement © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Supplement of What’s streamflow got to do with it? A probabilistic simulation of the competing oceanographic and fluvial processes driving extreme along-river water levels Katherine A. Serafin et al. Correspondence to: Katherine A. Serafin (kserafi[email protected]) The copyright of individual parts of the supplement might differ from the CC BY 4.0 License. 1 Hydraulic model domain and setup HEC-RAS model runs require detailed terrain information for the river network, including bathymetry and topography for the floodplains of interest. Topography data is sourced from a 2014 U.S Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) lidar survey (USACE, 2014). Bathymetry data is developed by blending two NOAA digital elevation models (DEM): National Geophysical Data 5 Center’s (NGDC) La Push, WA tsunami DEM (1/3 arc second; NGDC (2007)) and the coastal relief model (3 arc seconds; NGDC (2003)). These datasets, however, do not accurately resolve the channel depths of the Quillayute River inland of the coast, so a 2010 US Geological Survey (USGS)-conducted bathymetric survey of the river is also blended into the DEM (Czuba et al., 2010). In 2010, depths of along-river cross sections and an 11 km long longitudinal profile from the Bogachiel River to the mouth of 10 the Quillayute River were surveyed (Czuba et al., 2010). The survey of the longitudinal river profile also recorded the elevation of the water surface. -

Dr. Paolo Tarolli Viale Dell'universita, 16 35020 Legnaro PD, Italy

DEPARTMENT OF GEOPHYSICS May 24, 2019 Dr. Paolo Tarolli Viale dell’Universita, 16 35020 Legnaro PD, Italy Dear Dr. Tarolli, This letter accompanies the submission of the REVISED manuscript NHESS-2018-347 entitled, “What’s streamflow got to do with it? A probabilistic simulation of the competing oceanographic and fluvial processes driving extreme along-river water levels.” We have thoroughly considered and addressed the comments of the reviewers, and feel that this enabled us to better explain and clarify the overall framework and the importance of our results, strengthening the overall manuscript. Please find reviewer comments given in verbatim and our replies in italics. References to locations in the article are made by section (e.g., S3.5) or line number corresponding to the updated manuscript. The re-revised manuscript, which includes 14 figures, a supplemental information section, and this letter, has been uploaded. Thank you for your consideration. Please contact me at [email protected] with any questions. Sincerely, Katherine A. Serafin (lead and corresponding author) Postdoctoral Research Fellow Stanford University Department of Geophysics 397 Panama Mall, Mitchell Building, Stanford, CA 94305 T 650.497.6509 Anonymous Referee #1 Received and published: 4 March 2019 General comments Serafin et al present a new framework for examining the joint influence of several coastal and riverine processes on water levels in estuarine environments, and show very clearly that the 100-yr ocean or 100-yr streamflow event does not always produce the 100-yr along-river water level. It is a novel piece of work using a clever methodological framework, resulting in an analysis that can assesses non-stationary water levels from a multivariate joint distribution and truly decompose coastal water levels. -

The Sol Duc River System

The Sol Duc River System The Sol Duc River flows a total length of 64.9 miles in a westward direction from its source high in the north central Olympic Mountain range in the Olympic National Park (ONP) to its confluence with the Bogachiel and Quillayute Rivers roughly 5.5 miles from the Pacific Ocean. Its watershed is long and linear with elevations ranging from 5500 feet to 80 feet. For 5.3 miles, the Sol Duc forms the boundary between the ONP and the Olympic National Forest (ONF). Outside of the National Park, 11.1 miles of the Sol Duc lies entirely within the ONF and an additional 34.6 miles flow through private lands (22.5 miles) and state owned lands (12.1 miles). For the purposes of this analysis, the shorelines of the Sol Duc River are divided into 9 reaches (SOL DUC 10 through SOL DUC 90). Important features of each segment are presented in the tables below. A number of major tributary systems flow into the Sol Duc mainstem including the following creeks: Shuwah, Lake, Bockman, Beaver, Bear, Camp, and Goodman. Lake Creek also flows into the Sol Duc, but it and Lake Pleasant are addressed in a separate section. Most of these tributary systems join the Sol Duc mainstem within its middle reaches. The tributaries of the upper Sol Duc include SOLDUC S and the two tributaries GOODMAN and CAMP. The upper reaches of the Sol Duc and its tributaries flow through lands dedicated to commercial timberland uses and are not suitable for development.