11293 Report 19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Summary

executive summary This is the third report of the Oversight Commissioner for the year 2002.The objective is to report publicly on the progress in implementing the recommendations of the Independent Commission on Policing for Northern Ireland, as well as on any delays.The scope and magnitude of the changes recommended by the Independent Commission are unparalleled in modern-day policing, and recommendations will require a significant application of resources and effort.The Independent Commission also advised in the strongest terms against “cherry picking” from its report, and against trying to implement certain elements or recommendations in isolation from others. This report differs in style and format from previous oversight reports, in that it provides a more comprehensive overview of progress, from the Autumn of 2001 to the present.The reason is to provide the reader with an overall sense of how reforms are progressing as a whole.The underlying methodology of the oversight process remains unchanged. This report also contains comprehensive easy-to-read tables at page 69, which chart progress according to a number of specific categories.These are: recommendation completed, substantial progress, moderate progress, limited progress and minimal progress.The tables are based on the oversight team’s informed judgement, and should be read and interpreted both in the context of the main narrative segments of this report, as well as previous oversight reports.Although some of the recommendations were achieved in a relatively short period of time, such as those covering the Policing Board, the Ombudsman, police uniforms and symbols, others will of necessity occur in stages, and only over an extended period of time.As a result, the visible impact of many of the policing reforms will not be immediately apparent. -

Archived Content Contenu Archivé

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. In Search of Security: The Future of Policing in Canada LAW COMMISSION OF CANADA COMMISSION DU DROIT DU CANADA Ce document est également disponible en français : En quête de sécurité : l’avenir du maintien de l’ordre au Canada ISBN : JL2-26/2006F Catalogue : 0-662-71409-1 This Report is also available online at www.lcc.gc.ca. -

In Search of Security: the Future of Policing in Canada

In Search of Security: The Future of Policing in Canada LAW COMMISSION OF CANADA COMMISSION DU DROIT DU CANADA Ce document est également disponible en français : En quête de sécurité : l’avenir du maintien de l’ordre au Canada ISBN : JL2-26/2006F Catalogue : 0-662-71409-1 This Report is also available online at www.lcc.gc.ca. To order a copy of the Report, contact: Law Commission of Canada 222 Queen Street, Suite 1124 Ottawa ON K1A 0H8 Telephone: (613) 946-8980 Facsimile: (613) 946-8988 E-mail: [email protected] Cover illustration by David Badour. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Public Works and Government Services, 2006 ISBN: JL2-26/2006E Catalogue: 0-662-42902-8 The Honourable Vic Toews Minister of Justice Justice Building 284 Wellington Street Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0H8 Dear Honourable Minister: In accordance with section 5(1)(c) of the Law Commission of Canada Act, we are pleased to submit this Report by the Law Commission of Canada that examines the emergence of networks of policing in Canadian society and recommends changes to the legal and policy environment to reflect this new reality. Yours sincerely, Yves Le Bouthillier Bernard Colas President Commissioner Dr. Sheva Medjuck Mark L. Stevenson Commissioner Commissioner Roderick J. Wood Commissioner i Table of Contents Letter of Transmittal ..................................................................i Preface...........................................................................................vii Acknowledgments ....................................................................ix -

December 2019 / January 2020

The Police Federation of England & Wales www.polfed.org POLICEDecember 2019 / January 2020 Centenary celebrations at Central Hall Editor: Theo Boyce December / January – in this issue: Federation House, POLICE Highbury Drive, Leatherhead, NEWS & COMMENT Surrey, KT22 7UY Tel: 01372 352000 5 Editorial MPs’ inquiry into police watchdog welcomed Designer: Keith Potter 6 Outrage as Bonfire Night sees spate of attacks on officers Advertising agents: 7 Knife and violent crime rates continue to spiral Richard Place 8 View from the chair: John Apter takes time out to reflect Chestnut Media on a rollercoaster 12 months Tel: 01271 324748 Politics is a funny old game... P7 07962 370808 Email: 9 New Police Roll of Honour unveiled [email protected] 10 Centenary Celebration: Coverage of the special event to Every care is taken to ensure celebrate 100 years of the Police Federation that advertisements are accepted 14 Policing in Wales ‘should be run by the Welsh Government’ only from bona fide advertisers. The Police Federation cannot 15 PFEW Chair welcomes ‘working closer’ with the AMP accept any liability for losses 16 Public complaints against officers fall incurred by any person as a 17 Officers honoured at PFNDF result of a default on the part of P9 an advertiser. 18 Post-Incident Procedures Seminar: Officer suicides averted by welfare programme P10 The views expressed within PFEW campaigns outlined by National Board Members the magazine are not necessarily 22 Five minutes with John Apter the views of the National Board of the Police Federation of England 24 The latest on the pensions challenge and Wales. -

Human Rights Thematic Review: Policing with and for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Individuals Human Rights and Professional Standards Committee

Human Rights Thematic Review: Policing with and for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Individuals Human Rights and Professional Standards Committee FOREWORD The Human Rights Act 1998 requires the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) to uphold and protect the fundamental rights and freedoms of individuals that are enshrined in the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The Northern Ireland Policing Board (the Policing Board) has a statutory duty, under the Police (Northern Ireland) Act 2000, to monitor the performance of the PSNI in complying with the Human Rights Act. In 2003 the Policing Board appointed Human Rights Advisors who devised a human rights monitoring framework. The monitoring framework sets out in detail the standards against which the performance of the police in complying with the Human Rights Act is monitored by the Policing Board and identifies key areas to be examined. The Policing Board’s Human Rights and Professional Standards Committee (the Committee) is responsible for implementing the human rights monitoring framework. The Committee is assisted in this task by the Policing Board’s Human Rights Advisor. Every year since 2005, the Human Rights Advisor has presented the Committee with a Human Rights Annual Report. In recent years the Committee has enhanced its human rights monitoring work by introducing human rights thematic reviews. Thematic reviews enable a more in-depth and dynamic examination of specific areas of policing from a human rights perspective. A key feature of this approach is use of the community’s experience of policing as evidence by which to evaluate police policy and practice. The first thematic review, published in March 2009, examined the policing of domestic abuse. -

Police Advisory Board for England and Wales

OFFICIAL POLICE ADVISORY BOARD FOR ENGLAND AND WALES SEVENTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE INDEPENDENT CHAIR APRIL 2017 - MARCH 2018 2017-2018 OFFICIAL Foreword The Police Advisory Board for England and Wales (PABEW) was established as a non-departmental public body under section 46 of the Police Act 1964. During the year 2016, the PABEW was reclassified as a Stakeholder Group following a recommendation in the triennial review. Its membership and functions are set out in its constitution, which was revised and agreed in January 2015 and can be found at Annex C. It is tasked to: a. advise the Secretary of State on general questions affecting the police in England and Wales; b. consider draft regulations which the Secretary of State proposes to make under section 50 or section 52 of the Police Act 1996 with respect to matters other than hours of duty, leave, pay and allowances, or the issue, use and return of police clothing, personal equipment and accoutrements, or the ranks to be held by members of police forces, or the qualifications for appointment and promotion of members of police forces, or periods of service on probation, or the maintenance of personal records of members of police forces and to make such representations to the Secretary of State as it thinks fit; c. consider draft regulations which the Secretary of State proposes to make under section 37, 39, 81 or 83 of the Police Act 1997, and to make such representations to the Secretary of State as it thinks fit; d. consider draft regulations which the Secretary of State proposes to make under Part 2 of the Police Reform Act 2002, and to make such representations to the Secretary of State as it thinks fit; e. -

Police and Fire Reform (Scotland) Bill (SP Bill 8) As Introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 16 January 2012

This document relates to the Police and Fire Reform (Scotland) Bill (SP Bill 8) as introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 16 January 2012 POLICE AND FIRE REFORM (SCOTLAND) BILL —————————— POLICY MEMORANDUM INTRODUCTION 1. This document relates to the Police and Fire Reform (Scotland) Bill introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 16 January 2012. It has been prepared by the Scottish Government to satisfy rule 9.3.3(c) of the Parliament’s standing orders. The contents are entirely the responsibility of the Scottish Government and have not been endorsed by the Parliament. Explanatory notes and other accompanying documents are published separately as SP Bill 8–EN. POLICY OBJECTIVES OF THE BILL 2. Scotland has an excellent police service and fire and rescue service, with crime at a 35 year low and detection rates improving, helped by the 1,000 additional police officers the Government has put into communities, and fire deaths almost 50% lower than a decade ago. The Scottish Government is determined to protect and improve local police and local fire and rescue services in the face of reductions in public finance, by streamlining and modernising services. 3. The main policy objectives of this Bill are to create a single police service, and a single fire and rescue service, to deliver the policy aims set out below: • To protect and improve local services despite financial cuts, by stopping duplication of support services eight times over and not cutting front line services; • To create more equal access to specialist support and national capacity – like murder investigation teams, firearms teams or flood rescue – where and when they are needed; and, • To strengthen the connection between services and communities, by creating a new formal relationship with each of the 32 local authorities, involving many more local councillors and better integrating with community planning partnerships. -

Specials & Employers Covid-19 Support

SPRING 2020 | ISSUE 38 SPECIALS & EMPLOYERS COVID-19 SUPPORT SEE CENTRE PAGES Policing lead, Chief Constable local organisations inviting Lisa Winward, to pull together them to sign up to become an CHIEF CONSTABLE MESSAGE FROM guidance and resources, ESP partner. Spring Special Impact is working with partners and LISA WINWARD OF EDITOR: published at a very difficult time for stakeholders to assist We are working closely with NORTH YORKSHIRE us all. The Special Constabulary are WELCOMEand support Forces in the DutySheet, who have added vital as we continue to deal with the mobilisation of their Specials new features like, Social POLICE AND NPCC challenges that COVID-19 poses. I teams in a safe, considered Isolation and Social Distancing know that as volunteers in policing and meaningful way. In recent Module, so Forces can quickly LEAD FOR CITIZENS IN you are all doing everything you can weeks we have received a and easily identify, those to assist our communities at this unprecedented number of questions and as a available for deployment and POLICING time. I also want to mention the Employers of result put together documents, of course, offer support to our Special Constables; not only have our ESP to provide clarity over a range those in need. The system partners stepped up their support, but there of issues, informed by advice is also helping us to monitor are so many organisations that have offered to and guidance from the Home the number of hours served, to demonstration and report release their staff that are Special Constables As a police service, we Office, the College of Policing, on the enormous contribution to support policing which is amazing – if you greatly value our Special and others key stakeholders. -

Introduction

!!introduction This is the first report since my appointment as Oversight Commissioner in January of 2004. However, it is the tenth in a series of oversight reports that commenced in 2001. By way of a brief background, the Belfast, or Good Friday Agreement reached in 1998 led directly to the formation of the Independent Commission on Policing for Northern Ireland. This body was also known as the Patten Commission, and was tasked broadly with making recommendations designed to bring about a "new beginning" to policing in Northern Ireland. The Independent Commission published its report in September of 1999, Oversight Commissioner wherein it made 175 recommendations addressing the efficiency, Al Hutchinson acceptability and accountability of what is now the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI). The 175 recommendations were also designed to allow the new Police Service to draw on and sustain the support of the entire community of Northern Ireland. Also recommended was a period of independent monitoring of the recommendations’ full implementation, which ultimately led to the appointment of the first Oversight Commissioner, Mr. Tom Constantine, in May of 2000. He held this role until his retirement in December of 2003. As the first Oversight Commissioner,Tom Constantine applied his considerable law enforcement expertise and knowledge to instituting a viable oversight process. To support this process he assembled an accomplished oversight team, also made up of individuals with extensive professional policing and academic experience. The oversight team then established a rigorous set of objective standards and benchmarks, by which to measure progress on the implementation of all of the Independent Commission’s recommendations. -

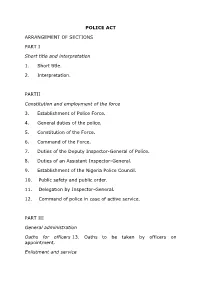

POLICE ACT ARRANGEMENT of SECTIONS PART I Short Title And

POLICE ACT ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I Short title and interpretation 1. Short title. 2. Interpretation. PARTII Constitution and employment of the force 3. Establishment of Police Force. 4. General duties of the police. 5. Constitution of the Force. 6. Command of the Force. 7. Duties of the Deputy Inspector-General of Police. 8. Duties of an Assistant Inspector-General. 9. Establishment of the Nigeria Police Council. 10. Public safety and public order. 11. Delegation by Inspector-General. 12. Command of police in case of active service. PART III General administration Oaths for officers 13. Oaths to be taken by officers on appointment. Enlistment and service 14. Enlistment. 15. Extension of term of enlistment in special cases. 16. Declarations. 17. Re-engagement. Supernumerary police officers 18. Appointment of supernumerary police officers to protect property. 19. Appointment of supernumerary police officers for employment on administrative duties on police premises. 20. Appointment of supernumerary police officers where necessary in the public interest. 21. Appointment of supernumerary police for attachment as orderlies. 22. Provisions supplementary to sections 18 to 21. PART IV Powers of police officers 23. Conduct of prosecutions. 24. Power to arrest without warrant. 25. Power to arrest without having warrant in possession. 26. Summonses. 27. Bail of person arrested without warrant. 28. Power to search. 29. Power to detain and search suspected persons. 30. Power to take fingerprints. PART V Property unclaimed, found or otherwise 31. Court may make orders with respect to property in possession of police. 32. Perishable articles. PART Vl Miscellaneous provisions 33. The Police Reward Fund. -

An Attitudinal Study of Police Officers and Police Community Support

POLICY CHANGE AND THE STREET LEVEL POLICING OF CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE IN A HOME COUNTIES POLICE FORCE by Judith Ann Mortimore A thesis submitted to the University of Bedfordshire for the Professional Doctorate in Youth Justice March 2011 POLICY CHANGE AND THE STREET LEVEL POLICING OF CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE IN A HOME COUNTIES POLICE FORCE J A MORTIMORE ABSTRACT New Labour‟s youth justice legislation and the „Every Child Matters‟ programme contained contradictory imperatives. This research examines how Police Officers and Police Community Support Officers (PCSOs) in a community policing setting operationalised those imperatives in order to reach decisions when dealing with children and young people. The review of literature focusses firstly on New Labour policy relating to children and young people, and secondly describes previous research into the practice of policing juveniles, the resilience of police culture and the key factors identified relating to police officer decision making. No recent British research in this area was located. Four overlapping hypotheses were identified, which were: officers will be more responsive to the „Every Child Matters‟ policy imperatives; officers will be more responsive to the criminal justice imperatives; managerialism will trump both sets of policy imperatives because it is in the officer‟s interests to respond to the demands of management; and both sets of policy imperatives and managerialism notwithstanding, officers will resort to „common sense‟ responses informed by their own lay criminologies, scales of values, police culture, and police „practice wisdom‟. ii These hypotheses were tested using quantitative and qualitative data from 198 self-reporting postal questionnaires and eight follow-up interviews. -

British Ltofar and Econo™

British Ltofar and Econo™ The Rhythms of Interaction with Mobile Technologies Tales from the Police Daniele Nicola Pica Department of Information Systems London School of Economics and Political Science Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE United Kingdom June 2006 Dissertation submitted in the fulfillment of the requirement for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the faculty of Economics at the University of London UMI Number: U228626 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U228626 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 TO MY MOTHER A bstr a c t This dissertation is concerned with understanding the dynamics surrounding the usage of Mobile Information and Communication Technologies (MICT) within the context of the police force in the United Kingdom. The opportunities arising from MICT and their rapid uptake have led to a great number of texts studying their impact and effectiveness. However, these studies have a superficial understanding of the context of use of MICT, are mainly concerned with improving the efficiency of one particular police task, and consider little usage of MICT as a technological, organizational or individual failure.