Oak Sapung Borer, Goes Tesselatus Haldeman1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Detecting Signs and Symptoms of Asian Longhorned Beetle Injury

DETECTING SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF ASIAN LONGHORNED BEETLE INJURY TRAINING GUIDE Detecting Signs and Symptoms of Asian Longhorned Beetle Injury TRAINING GUIDE Jozef Ric1, Peter de Groot2, Ben Gasman3, Mary Orr3, Jason Doyle1, Michael T Smith4, Louise Dumouchel3, Taylor Scarr5, Jean J Turgeon2 1 Toronto Parks, Forestry and Recreation 2 Natural Resources Canada - Canadian Forest Service 3 Canadian Food Inspection Agency 4 United States Department of Agriculture - Agricultural Research Service 5 Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources We dedicate this guide to our spouses and children for their support while we were chasing this beetle. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Detecting Signs and Symptoms of Asian Longhorned Beetle Injury : Training / Jozef Ric, Peter de Groot, Ben Gasman, Mary Orr, Jason Doyle, Michael T Smith, Louise Dumouchel, Taylor Scarr and Jean J Turgeon © Her Majesty in Right of Canada, 2006 ISBN 0-662-43426-9 Cat. No. Fo124-7/2006E 1. Asian longhorned beetle. 2. Trees- -Diseases and pests- -Identification. I. Ric, Jozef II. Great Lakes Forestry Centre QL596.C4D47 2006 634.9’67648 C2006-980139-8 Cover: Asian longhorned beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis) adult. Photography by William D Biggs Additional copies of this publication are available from: Publication Office Plant Health Division Natural Resources Canada Canadian Forest Service Canadian Food Inspection Agency Great Lakes Forestry Centre Floor 3, Room 3201 E 1219 Queen Street East 59 Camelot Drive Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario Ottawa, Ontario CANADA P6A 2E5 CANADA K1A 0Y9 [email protected] [email protected] Cette publication est aussi disponible en français sous le titre: Détection des signes et symptômes d’attaque par le longicorne étoilé : Guide de formation. -

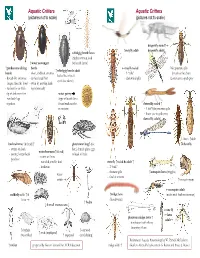

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (Pictures Not to Scale) (Pictures Not to Scale)

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (pictures not to scale) (pictures not to scale) dragonfly naiad↑ ↑ mayfly adult dragonfly adult↓ whirligig beetle larva (fairly common look ↑ water scavenger for beetle larvae) ↑ predaceous diving beetle mayfly naiad No apparent gills ↑ whirligig beetle adult beetle - short, clubbed antenna - 3 “tails” (breathes thru butt) - looks like it has 4 - thread-like antennae - surface head first - abdominal gills Lower jaw to grab prey eyes! (see above) longer than the head - swim by moving hind - surface for air with legs alternately tip of abdomen first water penny -row bklback legs (fbll(type of beetle larva together found under rocks damselfly naiad ↑ in streams - 3 leaf’-like posterior gills - lower jaw to grab prey damselfly adult↓ ←larva ↑adult backswimmer (& head) ↑ giant water bug↑ (toe dobsonfly - swims on back biter) female glues eggs water boatman↑(&head) - pointy, longer beak to back of male - swims on front -predator - rounded, smaller beak stonefly ↑naiad & adult ↑ -herbivore - 2 “tails” - thoracic gills ↑mosquito larva (wiggler) water - find in streams strider ↑mosquito pupa mosquito adult caddisfly adult ↑ & ↑midge larva (males with feather antennae) larva (bloodworm) ↑ hydra ↓ 4 small crustaceans ↓ crane fly ←larva phantom midge larva ↑ adult→ - translucent with silvery bflbuoyancy floats ↑ daphnia ↑ ostracod ↑ scud (amphipod) (water flea) ↑ copepod (seed shrimp) References: Aquatic Entomology by W. Patrick McCafferty ↑ rotifer prepared by Gwen Heistand for ACR Education midge adult ↑ Guide to Microlife by Kenneth G. Rainis and Bruce J. Russel 28 How do Aquatic Critters Get Their Air? Creeks are a lotic (flowing) systems as opposed to lentic (standing, i.e, pond) system. Look for … BREATHING IN AN AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT 1. -

Coleoptera, Cerambycidae, Lamiinae) with Description of a Species with Non‑Retractile Parameres

ARTICLE Two new genera of Desmiphorini (Coleoptera, Cerambycidae, Lamiinae) with description of a species with non‑retractile parameres Francisco Eriberto de Lima Nascimento¹² & Antonio Santos-Silva¹³ ¹ Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Museu de Zoologia (MZUSP). São Paulo, SP, Brasil. ² ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5047-8921. E-mail: [email protected] ³ ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7128-1418. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. In this study, two new genera of Desmiphorini (Lamiinae) are proposed: Cleidaria gen. nov., to include Cleidaria cleidae sp. nov. from the state of Chiapas in Mexico, and Obscenoides gen. nov. for Desmiphora (D.) compta Martins & Galileo, 2005. The shape of tarsal claws of Cleidaria cleidae sp. nov. (abruptly narrowed from basal half) is so far, not found in any current genera of the tribe. With respect to Obscenoides compta (Martins & Galileo, 2005) comb. nov., the genitalia of males have an unusual shape with non-retractile parameres. The character combination related to this genital structure is unknown to us in other species in the family, and hypotheses about its function are suggested. Key-Words. Genital morphology; Longhorned beetles; New taxa; Taxonomy. INTRODUCTION the current definitions of some tribes, especially based on the works of Breuning do not take into Lamiinae (Cerambycidae), also known as flat- account adaptive convergences and use superfi- faced longhorns, with more than 21,000 described cial characters to subordinate taxa. species in about 3,000 genera and 87 tribes is Among these tribes, Desmiphorini Thomson, the largest subfamily of Cerambycidae occurring 1860 is not an exception, and its “boundaries” are worldwide (Tavakilian & Chevillotte, 2019). -

Status of Forest Insect Pests

2006 Forest Insect and Disease Conditions for the Southern Region Most Significant Conditions in Brief The impact of serious pests was moderate to low in Southern forests in 2006. Abiotic factors were generally limited to latent effects from the 2005 Gulf Coast hurricanes, with some localized problems from windstorms and drought. There was a marked increase in scattered pine mortality across the western Gulf Coastal Plain from Alabama to Texas in response to drought and latent windstorm effects that increased their susceptibility to Ips and black turpentine beetle attack. The most significant new threat was the exotic ambrosia beetle Xyleborus glabratus, a native of India, Southeast Asia, and Japan that was first identified at Port Wentwortn, GA in 2002 and is vectoring an as-yet unnamed Raffaelea pathogen that kills redbay (Persea borbonia) and may pose a serious threat to other members of the family Lauraceae. The insect/disease complex currently occurs in fifteen Georgia counties, seven in South Carolina, and eight in Florida, and is spreading at a rate of approximately 20 miles per year. Southern pine beetle populations remained low throughout most of the Region, with notable exceptions in southwestern Alabama and in South Carolina. An increase in SPB activity was also noted in western Tennessee. Mortality of red oaks associated with drought, the red oak borer outbreak, and severe oak decline in north central Arkansas and northeastern Oklahoma continued, but has moderated. The oak resource in affected areas has been seriously impacted and severely affected stands are unlikely to regenerate to an oak forest without intervention. Infestations of the hemlock woolly adelgid continued to spread and intensify in the Southern Appalachians in 2006. -

A Guide to Arthropods Bandelier National Monument

A Guide to Arthropods Bandelier National Monument Top left: Melanoplus akinus Top right: Vanessa cardui Bottom left: Elodes sp. Bottom right: Wolf Spider (Family Lycosidae) by David Lightfoot Compiled by Theresa Murphy Nov 2012 In collaboration with Collin Haffey, Craig Allen, David Lightfoot, Sandra Brantley and Kay Beeley WHAT ARE ARTHROPODS? And why are they important? What’s the difference between Arthropods and Insects? Most of this guide is comprised of insects. These are animals that have three body segments- head, thorax, and abdomen, three pairs of legs, and usually have wings, although there are several wingless forms of insects. Insects are of the Class Insecta and they make up the largest class of the phylum called Arthropoda (arthropods). However, the phylum Arthopoda includes other groups as well including Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, shrimps, barnacles, etc.), Myriapoda (millipedes, centipedes, etc.) and Arachnida (scorpions, king crabs, spiders, mites, ticks, etc.). Arthropods including insects and all other animals in this phylum are characterized as animals with a tough outer exoskeleton or body-shell and flexible jointed limbs that allow the animal to move. Although this guide is comprised mostly of insects, some members of the Myriapoda and Arachnida can also be found here. Remember they are all arthropods but only some of them are true ‘insects’. Entomologist - A scientist who focuses on the study of insects! What’s bugging entomologists? Although we tend to call all insects ‘bugs’ according to entomology a ‘true bug’ must be of the Order Hemiptera. So what exactly makes an insect a bug? Insects in the order Hemiptera have sucking, beak-like mouthparts, which are tucked under their “chin” when Metallic Green Bee (Agapostemon sp.) not in use. -

Arthropods at Woodland Park Zoo Pre-Visit Information for Teachers

ARTHROPODS AT WOODLAND PARK ZOO PRE-VISIT INFORMATION FOR TEACHERS If you are planning a zoo field trip and wish to have your students focus on arthropods (insects, spiders, crustaceans and their relatives) during their visit, this pre-visit sheet can help them get the most out of their time at the zoo. We have put together an overview of key concepts related to arthropods, a list of basic vocabulary words, and a checklist of arthropod species at Woodland Park Zoo. Knowledge and understanding of these main ideas will enhance your students’ zoo visit. For more zoo information and activities focusing on arthropods, please call 206-548-2500 or download the Amazing Arthropods teacher packet at www.zoo.org. OVERVIEW: There are more different species of arthropods on Earth than any other group of living things. Scientists estimate that as much as 85% of the earth’s species are arthropods. Over 950,000 species of insects alone have been identified, compared to 4,000 species of mammals, 5,000 species of amphibians and 8,000 species of reptiles. Arthropods are found in habitats all over the world, from wingless flies in Antarctica to crabs and shrimp that live in extremely hot hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the ocean. Woodland Park Zoo exhibits a wide variety of arthropod species (see attached checklist) in a few different areas of the zoo. An arthropods field trip to the zoo could focus on the characteristics of arthropods (see “Concepts” below), comparing/contrasting different arthropods or learning about biomes and observing the physical characteristics of arthropods in different biomes. -

Gene to Genus: Systematics and Population Dynamics in Lamiini Beetles (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) with Focus on Monochamus Dejean

Gene to Genus: Systematics and Population Dynamics in Lamiini Beetles (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) With Focus on Monochamus Dejean The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Gorring, Patrick Scott. 2019. Gene to Genus: Systematics and Population Dynamics in Lamiini Beetles (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) With Focus on Monochamus Dejean. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42029751 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ! !"#"$%&$!"#'()$(*(%"+,%-.($,#/$0&0'1,%-&#$/*#,+-.($ $-#$1,+--#-$2""%1"($3.&1"&0%"4,)$."4,+2*.-/,"5$$ 6-%7$8&.'($&#$!"#"$%&!'()/"9",#! ! ! "!#$%%&'()($*+!,'&%&+(&#! -.! /)('$01!20*((!3*''$+4! (*! 56&!7&,)'(8&+(!*9!:'4)+$%8$0!)+#!;<*=>($*+)'.!?$*=*4.! ! $+!,)'($)=!9>=9$==8&+(!*9!(6&!'&@>$'&8&+(%! 9*'!(6&!#&4'&&!*9! 7*0(*'!*9!/6$=*%*,6.! $+!(6&!%>-A&0(!*9! ?$*=*4.! ! B)'<)'#!C+$<&'%$(.! D)8-'$#4&E!F)%%)06>%&((%! ! ",'$=!GHIJ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! K!GHIJ!/)('$01!20*((!3*''$+4! "==!'$46(%!'&%&'<&#L! ! !"##$%&'&"()*+,-"#(%.*/%(0$##(%*1%"')*!2*3'%%$44* *************** ***********************************************/'&%"56*7(%%")8* * * !"#"$%&$!"#'()$(*(%"+,%-.($,#/$0&0'1,%-&#$/*#,+-.($ $-#$1,+--#-$2""%1"($3.&1"&0%"4,)$."4,+2*.-/,"5$$ -

The Longhorned Beetles (Insecta: Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) of the George Washington Memorial Parkway

Banisteria, Number 44, pages 7-12 © 2014 Virginia Natural History Society The Longhorned Beetles (Insecta: Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) of the George Washington Memorial Parkway Brent W. Steury U.S. National Park Service 700 George Washington Memorial Parkway Turkey Run Park Headquarters McLean, Virginia 22101 Ted C. MacRae Monsanto Company 700 Chesterfield Parkway West Chesterfield, Missouri 63017 ABSTRACT Eighty species in 60 genera of cerambycid beetles were documented during a 17-year field survey of a national park (George Washington Memorial Parkway) that spans parts of Fairfax County, Virginia and Montgomery County, Maryland. Twelve species are documented for the first time from Virginia. The study increases the number of longhorned beetles known from the Potomac River Gorge to 101 species. Malaise traps and hand picking (from vegetation or at building lights) were the most successful capture methods employed during the survey. Periods of adult activity, based on dates of capture, are given for each species. Relative abundance is noted for each species based on the number of captures. Notes on plant foraging associations are noted for some species. Two species are considered adventive to North America. Key words: Cerambycidae, Coleoptera, longhorned beetles, Maryland, national park, new state records, Potomac River Gorge, Virginia. INTRODUCTION that feed on flower pollen are usually boldly colored and patterned, often with a bee-like golden-yellow The Cerambycidae, commonly known as pubescence. Nocturnal species are more likely glabrous longhorned beetles because of the length of their and uniformly dark, while bicolored species (often antennae, represent a large insect family of more than black and red) are thought to mimic other beetles which 20,000 described species, including 1,100 in North are distasteful. -

Cerambycidae of Tennessee

Cerambycidae of Tennessee! Disteniinae: Disteniini! Parandrinae: Parandriini! Closed circles represent previously published county records, museum specimen records, and specimens examined. Open circles are county records reported in Jamerson (1973) for which a specimen could not be located. Future collections are needed to substantiate these accounts. Fig. 2. Elytrimitatrix (Elytrimitatrix) undata (F.)! Fig. 3. Neandra brunnea (F.)! Prioninae: Macrotomini! Prioninae: Meroscheliscini! Fig. 4. Archodontes melanoplus melanoplus (L.)! Fig. 5. Mallodon dasystomus dasystomus Say! Fig. 6. Tragosoma harrisii (LeConte)! Prioninae: Prionini! Fig. 7. Derobrachus brevicollis Audinet-Serville! Fig. 8. Orthosoma brunneum (Forster)! Fig. 9. Prionus (Neopolyarthron) imbricornis (L.)! Prioninae! : Solenopterini! Fig. 10. Prionus (Prionus) laticollis (Drury) ! Fig. 11. Prionus (Prionus) pocularis Dalman ! Fig. 12. Sphenosethus taslei (Buquet) ! Necydalinae: Necydalini! Spondylidinae: Asemini! Fig. 13. Necydalis melitta (Say)! Fig. 14. Arhopalus foveicollis (Haldeman)! Fig. 15. Arhopalus rusticus obsoletus (Randall)! ! ! Suppl. Figs. 2-15. Tennessee county collection localities for longhorned beetle (Cerambycidae) species: Disteniinae, Parandrinae, Prioninae, Necydalinae, Spondylinae: Asemini (in part). ! Spondylidinae: Asemini (ctd.)! Fig. 16. Asemum striatum (L.)! Fig. 17. Tetropium schwarzianum Casey! Fig. 18. Atimia confusa confusa (Say)! ! Spondylidinae: Saphanini! Lepturinae: Desmocerini! Lepturinae: Encyclopini! Fig. 19. Michthisoma heterodoxum LeConte -

A Selective Bibliography on Insects Causing Wood Defects in Living Eastern Hardwood Trees By

Historic, Archive Document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. V1 Inited States epartment of .griculture A SELECTIVE Forest Service BIBLIOGRAPHY ON Bibliographies and Literature of Agriculture No. 15 INSECTS CAUSING t»4 WOOD DEFECTS IN LIVING EASTERN HARDWOOD TREES o cr-r m c m TO CO ^ze- es* A Selective Bibliography on Insects Causing Wood Defects in Living Eastern Hardwood Trees by C. John Hay Research Entomologist Forestry Sciences Laboratory Northeastern Forest Experiment Station U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Delaware, Ohio J. D. Solomon Principal Research Entomologist Southern Hardwoods Laboratory Southern Forest Experiment Station U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Stoneville, Miss. Bibliographies and Literature of Agriculture No. 15 U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service July 1981 3 8 Contents Introduction 1 Tylonotus bimaculatus Haldeman, ash and Host Tree Species 2 privet borer 18 Hardwood Borers Xylotrechus aceris Fisher, gallmaking maple borer*. 1 General and miscellaneous species 4 Curculionidae Coleoptera Conotrachelus anaglypticus Say, cambium curculio . 18 General and miscellaneous species 7 Cryptorhynchus lapathi (Linnaeus), poplar-and- Brentidae willow borer* 18 Arrhenodes minutus (Drury), oak timbenvorm* .. 8 Lymexylonidae Buprestidae Melittomma sericeum (Harris), chestnut General and miscellaneous species 9 timbenvorm* 22 Agrilus acutipennis Mannerheim 9 Scolytidae Agrilus anxius Gory, bronze birch borer* 9 General and miscellaneous species -

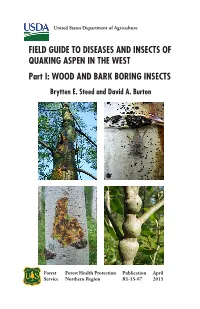

FIELD GUIDE to DISEASES and INSECTS of QUAKING ASPEN in the WEST Part I: WOOD and BARK BORING INSECTS Brytten E

United States Department of Agriculture FIELD GUIDE TO DISEASES AND INSECTS OF QUAKING ASPEN IN THE WEST Part I: WOOD AND BARK BORING INSECTS Brytten E. Steed and David A. Burton Forest Forest Health Protection Publication April Service Northern Region R1-15-07 2015 WOOD & BARK BORING INSECTS WOOD & BARK BORING INSECTS CITATION Steed, Brytten E.; Burton, David A. 2015. Field guide to diseases and insects FIELD GUIDE TO of quaking aspen in the West - Part I: wood and bark boring insects. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, Missoula DISEASES AND INSECTS OF MT. 115 pp. QUAKING ASPEN IN THE WEST AUTHORS Brytten E. Steed, PhD Part I: WOOD AND BARK Forest Entomologist BORING INSECTS USFS Forest Health Protection Missoula, MT Brytten E. Steed and David A. Burton David A. Burton Project Director Aspen Delineation Project Penryn, CA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Technical review, including species clarifications, were provided in part by Ian Foley, Mike Ivie, Jim LaBonte and Richard Worth. Additional reviews and comments were received from Bill Ciesla, Gregg DeNitto, Tom Eckberg, Ken Gibson, Carl Jorgensen, Jim Steed and Dan Miller. Many other colleagues gave us feedback along the way - Thank you! Special thanks to Betsy Graham whose friendship and phenomenal talents in graphics design made this production possible. Cover images (from top left clockwise): poplar borer (T. Zegler), poplar flat head (T. Zegler), aspen bark beetle (B. Steed), and galls from an unidentified photo by B. Steed agent (B. Steed). We thank the many contributors of photographs accessed through Bugwood, BugGuide and Moth Photographers (specific recognition in United States Department of Agriculture Figure Credits). -

Insects of Western North America 1

INSECTS OF WESTERN NORTH AMERICA 1. A Survey of the Cerambycidae (Coleoptera), or Longhomed Beetles of Colorado Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Department ofBioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management Colorado State University ISBN 1084-8819 Cover illustration. Moneilema armatum Leconte, illustration by Matt Leatherman. Copies of this publication may be ordered for $10. 00 from Gillette Museum ·of Arthropod Diversity, Department ofBioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523. Make check to Gillette Museum Publications. See inside back cover for other available publications. INSECTS OF WESTERN NORTH AMERICA 1. A Survey of the Cerambycidae (Coleoptera), or Longhomed Beetles, of Colorado by Daniel J. Heffern 10531 Goldfield Lane Houston, Texas 77064 1998 Figures 1-5. 1. Leptura propinqua Bland, Larimer Co., P.A. Opler; 2. Plectrodera scalator (Fabricius), Prowers Co., P.A. Opler; 3. Megacyllene robiniae (Forster), larvae, Larimer Co., S. Krieg; 4. Tetraopesfemoratus (LeConte), Larimer Co., P.A. Opler; 5. Monochamus c. clamator (LeConte), Larimer Co., D. Leatherman. i A Sunrey of the Cerambycidae (Coleoptera), or Longhorned Beetles of Colorado Daniel J. Heffern 10531 Goldfield Lane Houston, TX 77064 Abstract The purpose of this publication is to provide an account of the longhomed beetles of Colorado, to present new distributional records and to bring pertinent literature records together. One hundred ninety-three species and subspecies in 88 genera are listed, including thirty-eight new state records. The overall species distributions and host plants are included to provide an understanding of the zoogeography and possible origins of the species in the state. All available county records are included from the major institutional collections in Colorado, literature records, and numerous private collections.