Groarke JM Coetzee 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thursday, Dec. 1950

Second Day's Sale: THURSDAY, DEC. 1950 at 1 p.m. precisely LOT COMMONWEALTH (1649.60). 243 N Unite 1649, usual type with m.m. sun. Weakly struck in parts, otherwise extremely fine and a rare date. 244 A{ Crown 1652, usual type. The obverse extremely fine, the rev. nearly so. 245 IR -- Another, 1656 over 4. Nearly extremely fine. 246 iR -- Another, 1656, in good slate, and Halfcrown same date, Shilling similar, Sixpence 1652, Twopence and Penny. JtI ostly fine. 6 CROMWELL. 247* N Broad 1656, usual type. Brilliant, practically mint state, very rare. 1 248 iR Crown, 1658, usual type, with flaw visible below neck. Extremely fine and rare. 249 A{ Halfcrown 1658, similar. Extremely fine. CHARLES II (1660-85). 250* N Hammered Unite, 2nd issue, obu. without inner circle, with mark of value, extremely fine and rare,' and IR Hammer- ed Sixpence, 3rd issue, Threepence and Penny similar, some fine. 4 LOT '::;1 N Guinea 1676, rounded truncation. Very fine. ~'i2 JR Crowns 1662, rose, edge undated, very fine; and no rose, edge undated, fine. 3 _'i3 .-R -- Others, 1663, fine; and 1664, nearly very fine. 2 :?5-1 iR. -- Another, 1666 with elephant beneath bust. Very fine tor this rare variety. 1 JR -- Others, 1671 and 1676. Both better than fine. 2 ~56 JR -- Others of 1679, with small and large busts. Both very fine. 2 _57 /R -- Electrotype copy of the extremely rare Petition Crown by Simon. JR Scottish Crown or Dollar, 1682, 2nd Coinage, F below bust on obverse. A very rare date and in unttsually fine con- dition. -

Guide to the Collection of Irish Antiquities

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF SCIENCE AND ART, DUBLIN. GUIDE TO THE COLLECTION OF IRISH ANTIQUITIES. (ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY COLLECTION). ANGLO IRISH COINS. BY G COFFEY, B.A.X., M.R.I.A. " dtm; i, in : printed for his majesty's stationery office By CAHILL & CO., LTD., 40 Lower Ormond Quay. 1911 Price One Shilling. cj 35X5*. I CATALOGUE OF \ IRISH COINS In the Collection of the Royal Irish Academy. (National Museum, Dublin.) PART II. ANGLO-IRISH. JOHN DE CURCY.—Farthings struck by John De Curcy (Earl of Ulster, 1181) at Downpatrick and Carrickfergus. (See Dr. A. Smith's paper in the Numismatic Chronicle, N.S., Vol. III., p. 149). £ OBVERSE. REVERSE. 17. Staff between JiCRAGF, with mark of R and I. abbreviation. In inner circle a double cross pommee, with pellet in centre. Smith No. 10. 18. (Duplicate). Do. 19. Smith No. 11. 20. Smith No. 12. 21. (Duplicate). Type with name Goan D'Qurci on reverse. Obverse—PATRIC or PATRICII, a small cross before and at end of word. In inner circle a cross without staff. Reverse—GOAN D QVRCI. In inner circle a short double cross. (Legend collected from several coins). 1. ^PIT .... GOANDQU . (Irish or Saxon T.) Smith No. 13. 2. ^PATRIC . „ J<. ANDQURCI. Smith No. 14. 3. ^PATRIGV^ QURCI. Smith No. 15. 4. ^PA . IOJ< ^GOA . URCI. Smith No. 16. 5. Duplicate (?) of S. No. 6. ,, (broken). 7. Similar in type of ob- Legend unintelligible. In single verse. Legend unin- inner circle a cross ; telligible. resembles the type of the mascle farthings of John. Weight 2.7 grains ; probably a forgery of the time. -

A Study of Place in the Novels of VS Naipaul

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Towards a New Geographical Consciousness: A Study of Place in the Novels of V. S. Naipaul and J. M. Coetzee Thesis submitted by Taraneh Borbor for the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy in English literature The University of Sussex September 2010 1 In the Name of God 2 I declare that the work in this thesis was carried out in accordance with the regulations of the University of Sussex. The work is original except where indicated by special reference in the text and no part of the thesis has been submitted for any other degree. The thesis has not been presented to any other university for examination either in the United Kingdom or overseas. Signature: 3 ABSTRACT Focusing on approaches to place in selected novels by J. M. Coetzee and V. S. Naipaul, this thesis explores how postcolonial literature can be read as contributing to the reimagining of decolonised, decentred or multi-centred geographies. I will examine the ways in which selected novels by Naipaul and Coetzee engage with the sense of displacement and marginalization generated by imperial mappings of the colonial space. -

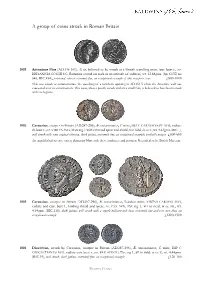

A Group of Coins Struck in Roman Britain

A group of coins struck in Roman Britain 1001 Antoninus Pius (AD.138-161), Æ as, believed to be struck at a British travelling mint, laur. bust r., rev. BRITANNIA COS III S C, Britannia seated on rock in an attitude of sadness, wt. 12.68gms. (Sp. COE no 646; RIC.934), patinated, almost extremely fine, an exceptional example of this very poor issue £800-1000 This was struck to commemorate the quashing of a northern uprising in AD.154-5 when the Antonine wall was evacuated after its construction. This issue, always poorly struck and on a small flan, is believed to have been struck with the legions. 1002 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C CARAVSIVS PF AVG, radiate dr. bust r., rev. VIRTVS AVG, Mars stg. l. with reversed spear and shield, S in field,in ex. C, wt. 4.63gms. (RIC.-), well struck with some original silvering, dark patina, extremely fine, an exceptional example, probably unique £600-800 An unpublished reverse variety depicting Mars with these attributes and position. Recorded at the British Museum. 1003 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, London mint, VIRTVS CARAVSI AVG, radiate and cuir. bust l., holding shield and spear, rev. PAX AVG, Pax stg. l., FO in field, in ex. ML, wt. 4.14gms. (RIC.116), dark patina, well struck with a superb military-style bust, extremely fine and very rare thus, an exceptional example £1200-1500 1004 Diocletian, struck by Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C DIOCLETIANVS AVG, radiate cuir. -

A REVIE\I\T of the COINAGE of CHARLE II

A REVIE\i\T OF THE COINAGE OF CHARLE II. By LIEUT.-COLONEL H. W. MORRIESON, F.s.A. PART I.--THE HAMMERED COINAGE . HARLES II ascended the throne on Maj 29th, I660, although his regnal years are reckoned from the death of • his father on January 30th, r648-9. On June 27th, r660, an' order was issued for the preparation of dies, puncheons, etc., for the making of gold and" silver coins, and on July 20th an indenture was entered into with Sir Ralph Freeman, Master of the Mint, which provided for the coinage of the same pieces and of the same value as those which had been coined in the time of his father. 1 The mint authorities were slow in getting to work, and on August roth an order was sent to the vVardens of the Mint directing the engraver, Thomas Simon, to prepare the dies. The King was in a hurry to get the money bearing his effigy issued, and reminders were sent to the Wardens on August r8th and September 2rst directing them to hasten the issue. This must have taken place before the end of the year, because the mint returns between July 20th and December 31st, r660,2 showed that 543 lbs. of silver, £r683 6s. in value, had been coined. These coins were considered by many to be amongst the finest of the English series. They fittingly represent the swan song of the Hammered Coinage, as the hammer was finally superseded by the mill and screw a short two years later. The denominations coined were the unite of twenty shillings, the double crown of ten shillings, and the crown of five shillings, in gold; and the half-crown, shilling, sixpence, half-groat, penny, 1 Ruding, II, p" 2. -

Coetzee's Stones: Dusklands and the Nonhuman Witness

Safundi The Journal of South African and American Studies ISSN: 1753-3171 (Print) 1543-1304 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsaf20 Coetzee’s stones: Dusklands and the nonhuman witness Daniel Williams To cite this article: Daniel Williams (2018): Coetzee’s stones: Dusklands and the nonhuman witness, Safundi, DOI: 10.1080/17533171.2018.1472829 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17533171.2018.1472829 Published online: 21 Jun 2018. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsaf20 SAFUNDI: THE JOURNAL OF SOUTH AFRICAN AND AMERICAN STUDIES, 2018 https://doi.org/10.1080/17533171.2018.1472829 Coetzee’s stones: Dusklands and the nonhuman witness Daniel Williams Society of Fellows, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Bringing together theoretical writing on objects, testimony, and J. M. Coetzee; testimony; trauma to develop the category of the “nonhuman witness,” this nonhuman; objects; essay considers the narrative, ethical, and ecological work performed ecocriticism; postcolonialism by peripheral objects in J. M. Coetzee’s Dusklands (1974). Coetzee’s insistent object catalogues acquire narrative agency and provide material for a counter-narrative parody of first-personal reports of violence in Dusklands. Such collections of nonhuman witnesses further disclose the longer temporality of ecological violence that extends beyond the text’s represented and imagined casualties. Linking the paired novellas of Dusklands, which concern 1970s America and 1760s South Africa, the essay finds in Coetzee’s strange early work a durable ethical contribution to South African literature precisely for its attention to nonhuman claimants and environments. -

Ancient, Islamic, British and World Coins Historical Medals and Banknotes

Ancient, Islamic, British and World Coins Historical Medals and Banknotes To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Upper Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1 Day of Sale: Thursday 29 November 2007 10.00 am and 2.00 pm Public viewing: 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Friday 23 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Monday 26 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 27 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Wednesday 28 November See below Or by previous appointment. Please note that viewing arrangements on Wednesday 28 November will be by appointment only, owing to restricted facilities. For convenience and comfort we strongly recommend that clients wishing to view multiple or bulky lots should plan to do so before 28 November. Catalogue no. 30 Price £10 Enquiries: James Morton, Tom Eden, Paul Wood or Stephen Lloyd Cover illustrations: Lot 172 (front); ex Lot 412 (back); Lot 745 (detail, inside front and back covers) in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Important Information for Buyers All lots are offered subject to Morton & Eden Ltd.’s Conditions of Business and to reserves. -

British Coins

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ BRITISH COINS 567 Eadgar (959-975), cut Halfpenny, from small cross Penny of moneyer Heriger, 0.68g (S 1129), slight crack, toned, very fine; Aethelred II (978-1016), Penny, last small cross type, Bath mint, Aegelric, 1.15g (N 777; S 1154), large fragment missing at mint reading, good fine. (2) £200-300 with old collector’s tickets of pre-war vintage 568 Aethelred II (978-1016), Pennies (2), Bath mint, long -

THE COINAGE of HENRY VII (Cont.)

THE COINAGE OF HENRY VII (cont.) w. J. w. POTTER and E. J. WINSTANLEY CHAPTER VI. Type V, The Profile Coins ALEXANDER DE BRUGSAL'S greatest work was the very fine profile portrait which he produced for the shillings, groats, and halves, and these coins are among the most beautiful of all the English hammered silver. It is true that they were a belated reply to the magnificent portrait coinage which had been appearing on the Continent since as early as 1465 but they have nothing to fear in comparison with the best foreign work. There has always been some doubt as to the date of the appearance of the new coins as there is no document extant ordering the production of the new shilling denomination, nor, as might perhaps be expected, is there one mentioning the new profile design. How- ever, as will be shown in the final chapter, there are good grounds for supposing that they first saw the light at the beginning of 1504. It has been suggested that experimental coins were first released to test public reaction to the new style of portrait, and that this was so with the groats is strongly supported by the marking used for what are probably the earliest of these, namely, no mint-mark and large and small lis. They are all rare and it is clear that regular production was not undertaken until later in 1504, while the full-face groats were probably not finally super- seded until early the following year. First, then, the shillings, which bear only the large and small lis as mark. -

History Workshop

UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND, JOHANNESBURG HISTORY WORKSHOP STRUCTURE AND EXPERIENCE IN THE MAKING OF APARTHEID 6-10 February 1990 AUTHOR: David Atwell TITLE: Ths " Labyrinth of My History " : The Struggle with Filiation in J. M. Costzee's Ousklands THE "LABYRINTH OF MY HISTORY": THE STRUGGLE WITH FILIATION IN J. M. COETZEE'S DVSKLANDS DAVID ATTWELL University of the Western Cape filiation is the name given by Edward Said to thai realm of nature or "life" that defines what is historically given to us by birth, circumstance or upbringing. Affiliation represents the process whereby filiative ties are broken and new ones formed, within cultural systems that constitute alternative sources of authority or coherence ("Secular Criticism" 16-20). The fiction of J. M. Coetzee can be described in terms of the way it embodies this shift; from the early work, in which colonialism is the stony ground on which consciousness and identity are formed, to the later, in which the inter-textual networks of literature are explored for their promise of partial, qualified forms of freedom. It would be a mistake, however, to read Life and Times ofMichael K and Foe as a-historical departures from the more socially critical Dusklands and In the Heart cf the Country. Affiliation is itself a historical process; it is the place where biography and culture meet. In Coetzee, it is also, among other things, a way of upholding a particular kind of critical consciousness, one that is always alert to both the disingenuous exercise of power, and the disingenuous representation of power. 1 In this essay, I am concerned with a small portion of the movement from filiation to affiliation within the corpus of Coetzee's novels: its beginnings in Dusklands. -

Self-Reflexivity in African Fiction: a Study on Coetzee’S Summertime

Indian J. Soc & Pol.1 (2): 21-24 : 2014 ISSN : 2348-0084 SELF-REFLEXIVITY IN AFRICAN FICTION: A STUDY ON COETZEE’S SUMMERTIME ASWATHY S M1 1Guest Lecturer, Dept. of English, Sree Narayana College for Women, Kollam, Kerala. INDIA ABSTRACT One of the things that distinguish postmodern aesthetic work from modernist work is extreme self-reflexivity. Postmodernists tend to take this even further than the modernists but in a way that tends often to be more playful, even irreverent. This same self-reflexivity can be found everywhere in pop culture, for example the way the Scream series of movies has characters debating the generic rules behind the horror film. In modernism, self-reflexivity tended to be used by "high" artists in difficult works .Post modernism, self-reflexive strategies can be found in both high art and everything from Seinfeld to MTV. In postmodern architecture, this effect is achieved by keeping visible internal structures and engineering elements (pipes, support beams, building materials, etc.). In many ways, postmodern artists and theorists and in Life and Times of Michael K. Coetzee‟s next novel, continue the sorts of experimentation that we can also find 1999s Disgrace, is a strong statement on the political in modernist works, including the use of self- climate in post–Apartheid South Africa. consciousness, parody, irony, fragmentation, generic Coetzee's Summertime opens and closes with mixing, ambiguity, simultaneity, and the breakdown journal entries, the only time the author (as character) between high and low forms of expression. In this way, speaks directly. The reader‟s temptation when reading postmodern artistic forms can be seen as an extension of Summertime is to try to work out what is brute fact, what modernist experimentation; however, others prefer to is irony, what is something else, but it‟s a temptation represent the move into postmodernism as a more radical which should be resisted. -

THE MICHAEL GIETZELT COLLECTION of BRITISH and IRISH COINS 14 NOVEMBER 2018

DIX • NOONAN • WEBB THE MICHAEL GIETZELT COLLECTION OF BRITISH and IRISH COINS 14 NOVEMBER 2018 COLLECTION OF BRITISH and IRISH COINS 14 NOVEMBER THE MICHAEL GIETZELT WEBB • DIX • NOONAN £25 THE MICHAEL GIETZELT COLLECTION www.dnw.co.uk OF BRITISH AND IRISH MILLED COINS 16 Bolton Street Mayfair London W1J 8BQ Wednesday 14 November 2018, 10:00 Telephone 020 7016 1700 Fax 020 7016 1799 email [email protected] 151 Catalogue 151 BOARD of DIRECTORS Pierce Noonan Managing Director and CEO 020 7016 1700 [email protected] Nimrod Dix Executive Chairman 020 7016 1820 [email protected] Robin Greville Head of Systems Technology 020 7016 1750 [email protected] Christopher Webb Head of Coin Department 020 7016 1801 [email protected] AUCTION SERVICES and CLIENT LIAISON Philippa Healy Head of Administration (Associate Director) 020 7016 1775 [email protected] Emma Oxley Accounts and Viewing 020 7016 1701 [email protected] Christopher Mellor-Hill Head of Client Liaison (Associate Director) 020 7016 1771 [email protected] Chris Rumney Client Liaison Europe (Numismatics) 020 7016 1771 [email protected] Chris Finch Hatton Client Liaison 020 7016 1754 [email protected] David Farrell Head of Logistics 020 7016 1753 [email protected] James King Deputy Head of Logistics 020 7016 1833 [email protected] COINS, TOKENS and COMMEMORATIVE MEDALS Christopher Webb Head of Department (Director) 020 7016 1801 [email protected] Peter Preston-Morley Specialist (Associate Director) 020 7016 1802 [email protected] Jim Brown Specialist 020 7016 1803 [email protected] Tim Wilkes Specialist 020