Nargiz Guliyeva

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

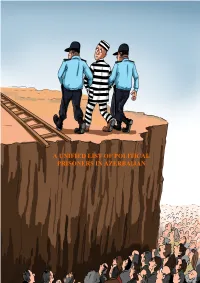

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 May 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS...............................................................5 POLITICAL PRISONERS.....................................................................................6-106 A. Journalists/Bloggers......................................................................................6-14 B. Writers/Poets…...........................................................................................15-17 C. Human Rights Defenders............................................................................17-18 D. Political and social Activists ………..........................................................18-31 E. Religious Activists......................................................................................31-79 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and those arrested in Nardaran Settlement...........................................................................31-60 (2) Persons detained in connection with the “Freedom for Hijab” protest held on 5 October 2012.........................60-63 (3) Religious Activists arrested in Masalli in 2012...............................63-65 (4) Religious Activists arrested in May 2012........................................65-69 (5) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested -

Khojaly Genocide

CHAPTER 1 KHOJALY. HISTORY, TRAGEDY, VICTIMS P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A RY Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan CONTENTS BRIEF HISTORY OF KARABAKH .............................................................................................................5 INFORMATION ON THE GRAVE VIOLATIONS OF HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTED DURING THE COURSE OF THE ARMENIAN AGGRESSION AGAINST AZERBAIJAN....................................7 BRIEF INFORMATION ABOUT KHOJALY ........................................................................................... 10 THE TRAGEDY........................................................................................................................................... 11 LIST OF THE PEOPLE DIED AT THE KHOJALY TRAGEDY ............................................................. 12 LIST OF FAMILIES COMPLETELY EXECUTED ON 26TH OF FEBRUARY 1992 DURING KHOJALY GENOCIDE .............................................................................................................................. 22 LIST OF THE CHILDREN DIED IN KHOJALY GENOCIDE ................................................................ 23 LIST OF THE CHILDREN HAVING LOST ONE OF THEIR PARENTS AT THE KHOJALY TRAGEDY.................................................................................................................................................... 25 LIST OF THE CHILDREN HAVING LOST BOTH PARENTS AT THE KHOJALY TRAGEDY ....... 29 MISSING PEOPLE ..................................................................................................................................... -

Truth Is Immortal

1 Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Republic of Azerbaijan HAVVA MAMMADOVA KHODJALY: MARTYRS AND WITNESSES Armenian terrorism as an integral part of the international one Baku 2006 2 Az.83.3 H 12 Translator: Aliyev Javanshir Aziz oglu Editor: Rahimova Vusala Novruz gyzy Proof-reader: Valiyev Hafiz Heydar oglu Havva Mammadova: Khodjali: Victims and Witnesses. Publishing House "House of Tales", Baku 2005, 248 pp. In this book there are used of materials, submitted by the Ministry of State Security of Azerbaijan Republic, the State Committee on affairs of the citizens taken prisoners, disappeared without a trace and taken hostage of Kodjali district Executive Power. The illustrations are taken from the photo archive of Azerbaijan State News Agency (AzerTadj) and the individual albums of the inhabitants of Khodjali. ISBN 9952-21-023-X © Havva Mammadova, 2006 © Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Republic of Azerbaijan 2006 3 BY THE AUTHOR "Heroic and courageous sons of our nation fighting for the sake of protection of our lands have become martyrs. But the Khodjaly tragedy has significant place in all of these events. From one hand it's a sample of faith of each Khodjaly inhabitant to own land, nation and Motherland. From other hand, it's a genocide caused by the nationalistic and barbarian forces of Armenia against Azerbaijan as well as an unprecedented expression of bigotry" Heydar Aliyev Khodjaly... In 1992 the name of this ancient settlement of Azerbaijan spread all over the world and the tragedy happened here remained in the history of mankind as one of the most murderous events. -

Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 03 September 2019 Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 3 THE DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS ...................................................................... 4 POLITICAL PRISONERS ................................................................................................................. 5 A. JOURNALISTS AND BLOGGERS ......................................................................................... 5 B. HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS ........................................................................................ 13 C. POLITICAL AND SOCIAL ACTIVISTS ............................................................................ 14 A case of financing of the opposition party ............................................................... 20 D. RELIGIOUS ACTIVISTS ...................................................................................................... 25 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and people arrested in Nardaran Settlement .............................................................................................................................. 25 (2) Religious activists arrested in Masalli in 2012 ................................................. 51 (3) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested together with him ................................................................................................................................. -

It Was Like Revisiting Aruba When I Wrote the Book”

A25 U.S. NEWS WEDNESDAY 15 JULY 2020 Wait ‘til next year: Giving up on 2020, looking toward 2021 Continued from Front having a microwedding June 6. As they did their first There was a months-long look, a massive Black Lives moment where the world Matter demonstration ar- was on pause, causing rived at Philadelphia’s Lo- many to dig into existential gan Square. Photos of the questions: What is my pur- couple holding hands, fists pose? Where do I belong? raised, with thousands of That’s what Dikobe found people surrounding them himself doing as he quaran- went viral. tined in his small New York “We were really just a sym- apartment contemplating bol of the things the world his future — both personal needs more of, especi- and professional. Would ally in 2020,” Perkins says. he ever perform on stage “There’s a pandemic and again, or would he have to all of the changes and the retire before an opportunity things that we’re hearing arrived? The more he consi- and seeing, people need dered it, the more he found hope. People need love. himself thinking: “2020 is not And people need unity.” canceled, actually. It’s an While Gordon says he awakening.” knows they were lucky, he Leslie Dwight, a 23-year-old has advice for others plan- writer, wondered the same A sign reads "Cancel Plans Not Humanity" Tuesday, April 14, 2020, in Los Angeles. ning milestones: Take a thing in a poem she wrote Associated Press breath, think about what’s that was endlessly shared “The only opportunity to ted to be. -

YOLUMUZ QARABAGADIR SON Eng.Qxd

CONTENTS Nationwide address of President Ilham Aliyev (27.09.2020) ..................4 A meeting of the Security Council chaired by President Ilham Aliyev ....9 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev in the "60 minutes" program on "Rossiya-1" TV channel ..........................................................................15 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Al Jazeera TV channel ..............21 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Al Arabiya TV channel ................35 Nationwide address of President Ilham Aliyev (04.10.2020) ..................38 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to TRT Haber TV channel ..............51 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Russian "Perviy Kanal" TV ........66 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to CNN-Tцrk Tv channel ................74 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Euronews TV channel ................87 Nationwide address of President Ilham Aliyev (09.10.2020) ..................92 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to CNN International TV channel's "The Connect World" program ................................................................99 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Sky News TV channel ................108 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Russian RBC TV channel ..........116 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Turkish Haber Global TV channel........................................................................129 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Turkish Haber Turk TV channel ..........................................................................140 -

Azerbaijan Page 1 of 18

2004 Country Report on Human Rights Practices in Azerbaijan Page 1 of 18 Azerbaijan Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2004 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 28, 2005 Azerbaijan is a republic with a presidential form of government. The Constitution provides for a division of powers between a strong presidency and parliament (Milli Majlis), which has authority to approve the budget and to impeach the President. The President dominated the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government. Ilham Aliyev, the son of former president Heydar Aliyev, was elected President in October 2003 in a ballot that did not meet international standards for a democratic election due to numerous, serious irregularities. There were similar irregularities during parliamentary elections in 2001 and 2003, and some domestic groups regarded the Parliament as illegitimate. Only 5 of the Parliament's 125 members were opposition members. The Constitution provides for an independent judiciary; however, it was corrupt, inefficient, and did not function independently. The Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) and Ministry of National Security are responsible for internal security and report directly to the President. Civilian authorities maintained effective control of security forces. Members of the security forces committed numerous human rights abuses. The Government continued programs to develop a market economy; however, the pace of reforms was uneven. The population was approximately 8 million, of which an estimated 2 million lived and worked abroad. Widespread corruption and patronage reduced competition. The slow pace of reform limited development outside the oil and gas sector, which accounted for more than 80 percent of export revenues. -

Reports of Local and Foreign Ngos on International Crimes Committed by Armenia During the Patriotic War (September 27 - November 10, 2020)

REPORTS of local and foreign NGOs on international crimes committed by Armenia during the Patriotic War (September 27 - November 10, 2020) Baku-2020 Reports of local and foreign NGOs on international crimes committed by Armenia during the Patriotic War (September 27 - November 10, 2020) Baku-2020. 364 pages. The book contains 12 reports on international crimes committed by Armenia against Azerbaijan during the Patriotic War, including 9 reports by local non- governmental organizations and 3 reports by foreign non-governmental organi- zations. The information is reflected in these reports on Armenia's use of weapons and ammunition prohibited by international conventions against civilians and civilian infrastructure in Azerbaijani towns and villages, deliberately killing people living far from the conflict zone, especially women and children, use terrorists and mercenaries in military operations, and involve children in hostilities, and facts about the pressure on the media and the constant suppression of freedom of speech, the destruction and appropriation of material, cultural, religious and natural monuments in the occupied territories, as well as looting of mineral re- sources, deforestation, deliberate encroachment on water bodies and the region to the brink of environmental disaster. Contents Patriotic War: REPORT on the causes of the outbreak, its consequences and the committed crimes 4 REPORT on the use of prohibited weapons by the armed forces of Armenia against the civilian population of Azerbaijan 26 REPORT on intentional killing, -

PRIVATE SECTOR ACTIVITY (PSA) Quarterly Progress Report

PRIVATE SECTOR ACTIVITY (PSA) Quarterly Progress Report Year 1. Quarter 1: September 18 – December 31, 2019 Jarchi Hagverdiyev’s team received recommendations regarding to the construction of warehouse in accordance to ISO 22000 Prepared for review by the United States Agency for International Development under USAID Contract No. 72011219C00001, Private Sector Activity (PSA) implemented by CNFA. Private Sector Activity Quarterly Progress Report September 18 – December 31, 2019 Submitted by: CNFA USAID Contract 72011219C00001 Implemented by CNFA Submitted to: USAID/Azerbaijan Samir Hamidov, COR Submitted on December 13, 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary................................................................................................................. 5 Detailed PSA Progress by Activity and Component ............................................................. 5 Operations ............................................................................................................................... 5 Legal Registration .................................................................................................................................... 8 Document and Deliverables Submission ............................................................................................ 8 Programs ................................................................................................................................ 10 Berry Value Chain ............................................................................................................................... -

Armenian Armed Forces Vanquish Azeri

Keghart Armenian Armed Forces Vanquish Azeri Attackers Non-partisan Website Devoted to Armenian Affairs, Human Rights https://keghart.org/mkrtchyan-armenian-forces-vanquish-azeri-attackers/ and Democracy ARMENIAN ARMED FORCES VANQUISH AZERI ATTACKERS Posted on July 31, 2020 by Keghart Category: Opinions Page: 1 Keghart Armenian Armed Forces Vanquish Azeri Attackers Non-partisan Website Devoted to Armenian Affairs, Human Rights https://keghart.org/mkrtchyan-armenian-forces-vanquish-azeri-attackers/ and Democracy By Karen Mkrtchyan, Yerevan, 30 July 2020 Between July 12-16, 2020, when the world was focused on fighting the global pandemic, Azerbaijani troops attacked Armenia. The attempted Azeri infiltration occurred in the northern Tavush province of Armenia--sovereign territory some 300 kilometers from the Republic of Artsakh (Nagorno Kharabagh), the usual target of Azeri aggression. Although through the years Azerbaijan has violated the ceasefire agreement on many occasions, this is the first major aggression since the four-day war of April 2016. As a result of Azerbaijan's cowardly attack six Armenian soldiers were killed. Casualties on the Azeri side were nearly double that number, with the Azeri authorities reporting 11 dead, among them high- ranking officers Major General Polad Hashimov, chief of staff of the North Military Unit and Col. Ilgar Mirzayev among others. Even the special "Yashma" troops, which President Aliyev has spent millions on to train in various parts of the world, could not yield the desired results for Baku. The Azeri forces suffered a heavy blow, raising doubts about Aliyev's continuous propaganda assertion that Azerbaijan’s superior army could wipe out Armenia off the map. -

Servicemen of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Azerbaijan That Awarded with the Medal for the Liberation of Shusha

Servicemen of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Azerbaijan that awarded with the Medal for the Liberation of Shusha President Ilham Aliyev has signed an order on awarding servicemen of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Azerbaijan with the Medal for the Liberation of Shusha. According to the order, the medal "For the Liberation of Shusha" was awarded to 4646 Azerbaijani servicemen, who demonstrated courage and bravery while participating in the military operations for the liberation of Shusha city from the Armenian occupation. One lieutenant generals, four major generals and thirty-one colonels, one hundred fourty one colonel lieutenant were among those who have been awarded. Mirzayev Hikmat Izzat oghlu – Lieutenant general Barkhudarov Mayis Shukur oghlu – Major general Mammadov Zaur Sabir oghlu – Major general Seyidov Kanan Alihuseyn oghlu – Major general Sultanov Aghamir Azizkhan oghlu – Major general Atakishiyev Eldar Aleksandr oghlu – Colonel Babayev Emil Sabir oghlu – Colonel Cahangirov Alakbar Mahammad oghlu – Colonel Cafarov Ceyhun Sadulla oghlu – Colonel Dadashov Hagverdi Khudaverdi oghlu – Colonel Ahmadov Bahadir Allahverdi oghlu – Medical service Colonel Ahmadov Etibar Isabala oghlu – Colonel Asadullayev Asif Azadkhan oghlu – Colonel Azizov Firudin Novruz oghlu – Colonel Faracov Asif Heydar oghlu – Colonel Hasanov Maharram Ashir oghlu – Colonel Ibrahimov Elman Adil oghlu – Colonel Israyilov Ragif Ibadulla oghlu – Colonel Gasimov Fuad Kamal oghlu – Colonel Guliyev Khalig Gulu oghlu – Colonel Guluyev Mais Isvandiyar oghlu – -

Khojaly Is Not Dead

Sariyya Muslum KHOJALY IS NOT DEAD 2007 Redactor: Adila Aghabeyli Scientific Worker in National Scientific Academy Translator: Narmin Abbasova “Shams-N” languages and translation center Painter: Vagif Ucatay Published: Cashoglu Publishing house KHOJALY IS NOT DEAD IN LIEU OF PREFACE OF AUTHOR .. .Once upon a time ..... No this story is a different one. It would be better to begin this story with: There were many big cities in the world, and a village named Khojaly. It is pity that now I am obliged to write about my native land, about my motherland in the past tense, and in narrative form. But at the end of my story Evil wins over the Good rather than Good over the Evil. ... Within fourteen years I try to be optimistic but I can’t. Greatness, even, the smell of grief named Khojaly has become familiar to me. Every year we commemorate black anniversary, tell our memories about that grief. By commemorating, by recalling it we reconcile with it. And now we gradually begin to forget about it. Though we haven’t right to this. .Again I dreamt about my mother. She was in a long, white dress. She was smiling. But whiteness of her dress pushed my shoulders in spite of dazzling my eyes; it didn’t let me to move. .Oh my God, how could the grief become familiar? My Khojaly grief .... That left my dreams and became a story. I know that while I wrote this book I absorbed into feelings, lost in emotions. But the readers can be sure that, the every fate, every story he will meet is real.