ARSC Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andrea Chénier

Synopsis France, late 18th century Act I A The Château de Coigny near Paris; spring, 1789 ER OP Act II AN Paris, along the Cours-la-Reine; spring, 1794 TROPOLIT Act III ME / The courtroom of the Revolutionary Tribunal; July 24, 1794 RD WA HO Act IV N St. Lazare Prison; July 25, 1794 KE 2013–14 A scene from Madama Butterfly Act I Preparations are under way for a party. Gérard, servant to the Countess de Coigny, is disgusted by the ways of the aristocracy. He riles against the servants’ life of slavery and prophesizes death to his masters. Maddalena, the countess’s daughter, appears and Gérard reflects on his secret love for her, while she complains to her servant, Bersi, about the discomfort of wearing fashionable e Metropolitan Opera is pleased clothes. Guests arrive, among them Fléville, a novelist, who has brought his friend, the poet Andrea Chénier. The latest distressing news from Paris is discussed, to salute Bank of America in then Fléville cheers the company with a pastorale he has written for the occasion. Maddalena teases a reluctant Chénier into improvising a poem. He responds recognition of its generous support with a rapturous description of the beauties of nature that turns into an appeal against tyranny and the suffering of the poor. The guests are offended but the during the 2013–14 season. countess begs their indulgence and commands a gavotte to begin. Just then, Gérard storms in with a group of starving peasants. Furious, the countess orders them out. Gérard takes off his livery, declaring he won’t have anything to do with the aristocracy any longer, and departs. -

191 VOCAL 78 Rpm Discs 2398. 11” Brown Praha Odeon 38539/38519

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs 2398. 11” Brown Praha Odeon 38539/38519 [XV62/Vx497]]. FRÜHLINGSZEIT (Becker) / WLADISLAV FLORIJANSKY [t]. EUGEN ONEGIN: Air (Tschaikowsky). Piano acc. Rare. Speeds 89.7/81.8 rpm, (presuming the key of A). Side one 4-5. Remarkably forward and the graying sounds only a bit. Side one 3-4 (although hardly any graying). Looks considerably worse than it sounds. $50.00. GIUSEPPE PACINI [b]. Firenze, 1862-1910. His debut was in Firenze, 1887, in Verdi’s I due Foscari. In 1895 he appeared at La Scala in the premieres of Mascagni’s Guglielmo Ratcliff and Silvano. Other engagements at La Scala followed, as well as at the Rome Costanzi, 1903 (with Caruso in Aida) and other prominent Italian houses. He also appeared in Mexico and the Phil- lipines. Among the leading baritones of his era, Pacini’s only records were a few for Fonotipia. 9024. 11” Gold SS Fonotipia 39005 [XPh2]. LE ROI DE LAHORE: O casto fior (Massenet). Few MGTs, just about 2. $50.00. REGINA PACINI [s]. Lisbon, 1871-Buenos Aires, 1965. Born of a musical family, Pacini made her debut in 1888 at the San Carlo in Lisbon as Amina in Bellini’s La Sonnambula. She also appeared at La Scala, Covent Garden (with Caruso), Rome, Warsaw and St. Petersburg. In Buenos Aires, 1907, Pacini wed the Argentine Diplomat Marcelo de Alvear and then retired from the stage. From 1922 through 1928 she was first lady of Argentina, her husband having been elected President. Pacini was still living during the reign of another more recognized Argentine presidential wife, Evita Peron. -

83383 Vocal Promo4color

CONTENTS Includes releases from Fall 2001 through 2003 The Vocal Library.............................................................................................2 Joan Boytim Publications .................................................................................5 Art Song............................................................................................................6 Opera Collections.............................................................................................8 Opera Vocal Scores and Individual Arias ......................................................13 Ricordi Opera Full Scores...............................................................................15 Leonard Bernstein Theatre Publications........................................................16 Musical Theatre Collections ..........................................................................17 Theatre and Movie Vocal Selections .............................................................20 Solos for Children...........................................................................................23 Jazz and Standards...........................................................................................24 Solo Voice and Jazz Ensemble ........................................................................25 Jazz and Pop Vocal Instruction .......................................................................26 Popular Music .................................................................................................27 Collections................................................................................................27 -

Ayout 1 6/9/08 4:28 PM Page 1

20765_VocalMusic:Layout 16/9/084:28PMPage Recent Releases&Highlights Samuel Barber: Mother, I cannot mind my wheel composer’s manuscript, © 2008 by G. Schirmer, Inc. first published in Barber: Ten Selected Songs 20765_VocalMusic:Layout 1 6/9/08 4:28 PM Page 2 www.halleonard.com This brochure of highlighted recent publications is only a small portion of our thousands of solo vocal and opera titles. We invite you to search online at www.halleonard.com for other publications. We have a complete Hal Leonard Vocal Catalog available, which includes all vocal publications and opera scores through early 2006. To request your free copy, please contact us: • by email to [email protected] • by mail to: Hal Leonard Corporation attn: Vocal Catalog Request 7777 W. Bluemound Road Milwaukee, WI 53213 Throughout this brochure, publications with companion CDs are marked with this icon: CHANGE THE KEY, CHANGE THE TEMPO ON CDS Our most recent companion CDs include new CD-ROM software that allows you to transpose to any key and change the tempo. You can even change the tempo without changing the pitch. This means that the key or tempo of accompaniment tracks on these enhanced CDs, when played in a computer as a CD-ROM, can be adjusted for an individual singer’s needs. This CD-ROM software, the Amazing Slow Downer was originally created for use in pop music, but we have adapted it for classical and theatre use. It is added without additional cost on recent companion CD releases. The transposing and tempo adjustment features work only when using these enhanced CDs in a computer, as a CD-ROM. -

Andrea Chénier

Andrea Chénier La Fenice prima dell’Opera 2002-2003 6 FONDAZIONE TEATRO LA FENICE DI VENEZIA Andrea Chénier dramma di ambiente storico in quattro quadri libretto di Luigi Illica musica di Umberto Giordano PalaFenice sabato 19 aprile 2003 ore 20.00 turni A-L martedì 22 aprile 2003 ore 20.00 turni D-O giovedì 24 aprile 2003 ore 20.00 turni E-F-P-T domenica 27 aprile 2003 ore 15.30 turni B-M martedì 29 aprile 2003 ore 17.00 turni C-G-N-S-U Gaetano Esposito (1858-1911). Ritratto di Umberto Giordano. Olio su tela, 1896 (Napoli, Conservatorio di San Pietro a Majella). Sommario 7 La locandina 9 «Allons, enfants de la Patrie!» di Michele Girardi 11 Andrea Chénier, libretto e guida all’opera a cura di Giorgio Pagannone 73 Andrea Chénier in breve a cura di Gianni Ruffin 75 Argomento – Argument – Synopsis – Handlung 81 Marco Emanuele «Son donna e son curiosa» e non so nemmeno cantare: maschile e femminile in Andrea Chénier 103 Giovanni Guanti Andrea Chénier, o la carriera di un girondino 123 Cecilia Palandri Bibliografia 129 Online: Revisionismo all’opera a cura di Roberto Campanella 137 Umberto Giordano a cura di Mirko Schipilliti 143 Andrea Chénier a Venezia (1961-2003) Locandina della prima rappresentazione di Andrea Chénier. Andrea Chénier dramma di ambiente storico in quattro quadri libretto di Luigi Illica musica di Umberto Giordano Casa Musicale Sonzogno di Piero Ostali, Milano personaggi ed interpreti Andrea Chénier Fabio Armiliato Carlo Gérard Alberto Gazale Maddalena di Coigny Daniela Dessì La mulatta Bersi Rossana Rinaldi Madelon Olga Alexandrova -

Callas-Tebaldi: La Rivalidad Mediática Ricardo De Cala

Callas-tebaldi: la rivalidad mediática Ricardo de Cala El mundo operístico de los años 50 quedó con- Magazine en la que la gran soprano aparecía arro- vulsionado por la rivalidad de dos grandes sopra- pada con el imponente traje de Tosca y coronada nos que polarizaron la atención en ámbitos que con una soberbia tiara. En ella era todo era como incluso excedían el musical. Si observamos con se suponía que debía ser una rutilante soprano detenimiento este supuesto enfrentamiento ve- internacional. remos que en realidad se superponían dos eco- sistemas completamente diferentes tanto en lo María Kalogeropoulos, María Callas para el mun- personal como en lo simbólico y lo artístico. do del arte, era todo lo contrario. En ella todo era excesivo, desmesurado. Cuando la Callas llegó al La Tebaldi representaba la gran diva-soprano tra- mundo de la ópera ocasionó un terremoto artís- dicional. Siempre impecable envuelta en lujosas tico como luego tendremos ocasión de compro- pieles, sonriente, imperial, adornada con joyas bar. En la vida, al principio nos encontramos con fabulosas. Recordemos aquella portada de Time aquella mujerona voluminosa, poca gracia en el 4 vestir y volcada constantemente en su arte. Elsa papeles que cantaron las dos, incluso casi podría- Maxwell la introdujo en la deslumbrante alta so- mos circunscribir la competencia a un sólo papel ciedad de los años 50, la visión de la estilizada que ambas encarnaron recurrentemente sobre el y glamurosa Audrey Hepburn en Vacaciones en escenario y que es el de Tosca. Aida, por ejemplo, Roma la impresionó profundamente y el mag- fue un papel que cantaron ambas sopranos pero netismo hipnótico de Aristóteles Onassis hizo el la Callas lo hizo al principio de su carrera y per- resto. -

THE MUNICH OPERA FESTIVAL Six Major Performances Sunday, July 14Th Through Monday, July 22Nd

THE MUNICH OPERA FESTIVAL Six Major Performances Sunday, July 14th through Monday, July 22nd Nationaltheater, home of Bavarian State Opera “Munich’s Opera Festival , a mix of brand-new productions, stag - s in most recent years, Munich’s traditional summer Opera ings from the past season and immaculately cast revivals, has become Festival in 2019 will offer an undeniable richness of six perhaps the most dependably, densely exciting presentation of opera major performances within a compact seven-night pe - in the world… Opera is hardly ever perfect. But in Munich these days riod . Reflecting the variety of the repertoire and the superla - A tive casting, our mid-July week promises to be the highlight it comes closer, consistently, than anywhere else I know. ” NY Times of our summer offerings. In chronological order, the op - Anna Netrebko: “A genuine superstar for the 21st cen - eras on our program will be Gluck’s rarely encountered classical ‘reform opera’, Alceste ; Bedrich Smetana’s tury” Musical America Czech lyric comedy, The Bartered Bride ; Verdi’s tow - ering Shake spearean tragedy, Otello ; Giordano’s popular Jonas Kaufmann: “Almost certainly the greatest tenor in verismo vehicle, Andrea Chénier ; and Puccini’s dra - the world right now, a dashingly handsome German with matic final work for the stage, Turandot . Three of these an extraordinary voice, whose career is reaching new peaks works will be staged in new productions – Alceste, The with each year.” The Telegraph Bartered Bride, and Otello. Jonas Kaufmann “Maestro Kyrill Petrenko once again discovered and com - Among the sensational casts are Jonas Kaufmann, Anja Harteros and Gerald Finley for ‘Otello’; Nina Stemme municated a new level of brilliance in a familiar master - in the title role of ‘Turandot’; Dorothea Röschmann as piece. -

Download Booklet

110275-76 bk Giordano US 22/08/2003 13:32 Page 12 Great Opera Recordings ADD 8.110275-76 Also available: 2 CDs GIORDANO Andrea Chénier Beniamino Gigli Maria Caniglia Gino Bechi Giulietta Simionato Chorus and Orchestra of La Scala, Milan 8.110262 Oliviero de Fabritiis (Recorded in 1941) 8.110275-76 12 110275-76 bk Giordano US 22/08/2003 13:32 Page 2 Great Opera Recordings Umberto GIORDANO Also available: (1867 – 1948) Andrea Chénier Opera in Four Acts Libretto by L. Illica Maddalena di Coigny . Maria Caniglia Andrea Chénier . Beniamino Gigli Carlo Gérard . Gino Bechi Countess di Coigny . Giulietta Simionato Madelon . Vittoria Palombini Bersi . .Maria Huder Roucher . Italo Tajo Fouquier-Tinville . Giuseppe Taddei Mathieu . Leone Paci Fléville . Giuseppe Taddei The Abbé . Adelio Zagonara L’Incredibile . Adelio Zagonara Majordomo . Gino Conti Dumas . Gino Conti Schmidt . Gino Conti Orchestra and Chorus of La Scala Opera House, Milan Conducted by Oliviero de Fabritiis 8.110096-97 Recorded in Milan by La voce del padrone on 26 sides, November 1941 Matrices: 2BA 4787-4812; catalogue: DB5423-35 8.110275-76 2 11 8.110275-76 110275-76 bk Giordano US 22/08/2003 13:32 Page 10 Producer’s Note CD 1 53:41 ! Calligrafia invero femminil! 2:14 (Roucher, Chénier) This recording of Andrea Chénier, made by Italian HMV during World War II, was first published on pressings Act I 28:14 manufactured in Italy specifically for the Italian market. Although these pressings are free of the crackle that often @ Ecco laggiù Gérard! 3:07 afflicts British HMV pressings, they yield too high a degree of surface hiss for them to be a good source for digital 1 Questo azzurro sofà 4:40 (La folla, Mathieu, L’Incredibile, Chénier, transfer. -

To View Program

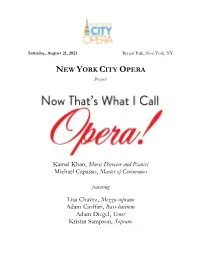

Saturday, August 21, 2021 Bryant Park, New York, NY NEW YORK CITY OPERA Presents Kamal Khan, Music Director and Pianist Michael Capasso, Master of Ceremonies featuring Lisa Chavez, Mezzo-soprano Adam Cioffari, Bass-baritone Adam Diegel, Tenor Kristin Sampson, Soprano PROGRAM Les contes d'Hoffmann Offenbach Barcarolle: Belle nuit, ô nuit d'amour Lisa Chavez Nicklausse Kristin Sampson Giulietta Faust Gounod Vous qui faites l'endormie Adam Cioffari Méphistophélès Manon Lescaut Puccini Tu, tu, amore? Tu? Kristin Sampson Manon Adam Diegel Des Grieux Adriana Lecouvreur Cilea Acerba Volutta Lisa Chavez Princess de Bouillon Don Giovanni Mozart Là ci darem la mano Adam Cioffari Don Giovanni Kristin Sampson Zerlina Die Walküre Wagner Winterstürme wichen dem Wonnemond Adam Diegel Siegmund Le Nozze di Figaro Mozart Sull’aria Lisa Chavez Countess Almaviva Kristin Sampson Susanna La bohème Puccini O Mimì tu più non torni Adam Diegel Rodolfo Adam Cioffari Marcello Andrea Chénier Giordano La mamma morta Kristin Sampson Maddalena Carmen Bizet Finale: C’est toi! C’est moi! Lisa Chavez Carmen Adam Diegel Don José La traviata Verdi Libiamo ne’lieti calici Lisa Chavez Adam Diegel Adam Cioffari Kristin Sampson BRYANT PARK SUMMER PICNIC PERFORMANCES NEW YORK CITY OPERA-SUMMER 2021 RIGOLETTO September 3, 2021: Bryant Park Upper Terrace 7:00 pm – 8:30 pm Michael Capasso, Director Constantine Orbelian, Conductor CAST Rigoletto: Michael Chioldi The Duke of Mantua: Won Whi Choi Gilda: Brandie Sutton Maddalena: Lisa Chavez Sparafucile: Kevin Short ABOUT NEW YORK CITY OPERA Since its founding in 1943 by Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia as “The People’s Opera,” New York City Opera has been a critical part of the city’s cultural life. -

00028947950189.Pdf

VERISMO V ANNA NETREBKO VERISMO VERISMO V FRANCESCO CILEA (1866–1950) ALFREDO CATALANI (1854–1893) Manon Lescaut Adriana Lecouvreur La Wally Libretto: Domenico Oliva, Luigi Illica, Libretto: Arturo Colautti Libretto: Luigi Illica Ruggero Leoncavallo, Marco Praga, Giulio Ricordi, Giuseppe Adami A Act I: “Ecco: respiro appena … 3:42 F Act I: “Ebben? Ne andrò lontana” 3:55 K Act II: “In quelle trine morbide” 2:48 Io son l’umile ancella” (Adriana) (Wally) (Manon) UMBERTO GIORDANO (1867–1948) ARRIGO BOITO (1842–1918) Act IV L Andrea Chénier Mefistofele “Tutta su me ti posa” 2:56 (Des Grieux, Manon) Libretto: Luigi Illica Libretto: Arrigo Boito M “Manon, senti, amor mio” 1:59 B Act III: “La mamma morta” 4:59 G Act III: “L’altra notte in fondo 6:53 (Des Grieux, Manon) (Maddalena) al mare” (Margherita) N “Sei tu che piangi?” 4:38 (Manon, Des Grieux) GIACOMO PUCCINI (1858–1924) AMILCARE PONCHIELLI (1834–1886) O “Sola, perduta, abbandonata” 4:25 Madama Butterfly La Gioconda (Manon) Libretto: Giuseppe Giacosa, Luigi Illica Libretto: Tobia Gorrio [Arrigo Boito] P “Fra le tue braccia, amore” 6:42 C Act II: “Un bel dì vedremo” (Butterfly) 4:35 H Act IV: “Suicidio! In questi fieri 4:35 (Manon, Des Grieux) Turandot momenti” (Gioconda) Libretto: Giuseppe Adami, Renato Simoni GIACOMO PUCCINI D Act I: “Signore, ascolta!” (Liù) 2:41 Tosca Libretto: Giuseppe Giacosa, Luigi Illica RUGGERO LEONCAVALLO (1857–1919) I Pagliacci Act II: “Vissi d’arte, vissi d’amore” 3:27 ANNA NETREBKO soprano Der Bajazzo · Paillasse (Tosca) YUSIF EYVAZOV tenor (J, L–N, P) J Libretto: Ruggero Leoncavallo Turandot CORO DELL’ACCADEMIA NAZIONALE DI SANTA CECILIA ( ) ORCHESTRA DELL’ACCADEMIA NAZIONALE DI SANTA CECILIA E Act I: “Qual fiamma avea nel 4:32 J Act II: “In questa reggia” 6:12 ANTONIO PAPPANO guardo! … Stridono lassù” (Nedda) (Turandot, coro, Calaf) Sir Antonio Pappano appears courtesy of Warner Classics. -

Andrea Chenier,Appunti Di Ricerca E Note Di Mario Mainino

Andrea Chenier, appunti di ricerca e note di Mario Mainino Andrea Chénier è un'opera lirica in quattro quadri di Umberto Giordano su libretto di Luigi Illica. Dramma di ambiente storico ispirato alla vita del poeta francese André Chénier, all'epoca della rivoluzione francese, è la più famosa opera lirica di Giordano. Il personaggio di Carlo Gérard è ispirato al rivoluzionario Jean-Lambert Tallien. Il 28 marzo 1896 avvenne la prima assoluta al Teatro alla Scala di Milano diretta da Rodolfo Ferrari, con Giuseppe Borgatti, che sostituì il tenore designato Alfonso Garulli, anche se era in un periodo non positivo, ma, anche grazie al soprano Evelina Carrera ed al baritono Mario Sammarco, il successo fu trionfale. Il soggetto è ricavato da un romanzo di Joseph Méry, imitatore di Dumas e di Sue. “Romanzo popolare intriso di avventure e lacrime, insaporite da melodie appassionate e cantabili … Ogni atto finisce con un colpo di scena da rovesciare nel successivo … Tocca alla musica colorire e riscaldare la materia in modo che lo spettatore, sommerso dall’onda melodica, digerisca le assurdità storiche e letterarie. In quest'ottica L'opera è addirittura perfetta con le arie che esplodono nei momenti culminanti e il grande duetto finale, affidato al canto spiegato e dalla più suadente delle melodie. Tanto perfetta da sopravvivere Nel cuore dei meloni che, a torto o a ragione, preferiscono il fumetto musicale fatto in casa. ” Rubens Tedeschi 1955 Maddalena = Maria Callas 1960-01-08 Mario Del Monaco (Franco Corelli), Renata Tebaldi, Ettore Bastianini, -

In Search of the "True" Sound of and Artist : a Study of Recordings by Maria Callas

IN SEARCH OF THE “TRUE” SOUND OF AN ARTIST: A STUDY OF RECORDINGS BY MARIA CALLAS Adriaan Fuchs Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (Music Technology) in the Faculty of Arts, Stellenbosch University. APRIL 2006 Supervisor: Mr. T Herbst Co-supervisor: Prof. HJ Vermeulen DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously, in its entirety or in part, submitted it at any university for a degree. …………………… …………………… Adriaan Fuchs Date ii ABSTRACT Modern digital signal processing, allowing a much greater degree of flexibility in audio processing and therefore greater potential for noise removal, pitch correction, filtering and editing, has allowed transfer and audio restoration engineers a diversity of ways in which to “improve” or “reinterpret” (in some cases even drastically altering) the original sound of recordings. This has lead to contrasting views regarding the role of the remastering engineer, the nature and purpose of audio restoration and the ethical implications of the restoration process. The influence of audio restoration on the recorded legacy of a performing artist is clearly illustrated in the case of Maria Callas (1923 - 1977), widely regarded not only as one of the most influential and prolific of opera singers, but also one of the greatest classical musicians of all time. EMI, for whom Callas recorded almost exclusively from 1953 - 1969, has reissued her recordings repeatedly,