1 Narrative Mapping by Stephen Mamber UCLA Dept. of Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Realistic Modeling and Rendering of Plant Ecosystems

Realistic modeling and rendering of plant ecosystems Oliver Deussen1 Pat Hanrahan2 Bernd Lintermann3 RadomÂõr MechÏ 4 Matt Pharr2 Przemyslaw Prusinkiewicz4 1 Otto-von-Guericke University of Magdeburg 2 Stanford University 3 The ZKM Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe 4 The University of Calgary Abstract grasslands, human-made environments, for instance parks and gar- dens, and intermediate environments, such as lands recolonized by Modeling and rendering of natural scenes with thousands of plants vegetation after forest ®res or logging. Models of these ecosystems poses a number of problems. The terrain must be modeled and plants have a wide range of existing and potential applications, including must be distributed throughout it in a realistic manner, re¯ecting the computer-assisted landscape and garden design, prediction and vi- interactions of plants with each other and with their environment. sualization of the effects of logging on the landscape, visualization Geometric models of individual plants, consistent with their po- of models of ecosystems for research and educational purposes, sitions within the ecosystem, must be synthesized to populate the and synthesis of scenes for computer animations, drive and ¯ight scene. The scene, which may consist of billions of primitives, must simulators, games, and computer art. be rendered ef®ciently while incorporating the subtleties of lighting Beautiful images of forests and meadows were created as early in a natural environment. as 1985 by Reeves and Blau [50] and featured in the computer We have developed a system built around a pipeline of tools that animation The Adventures of Andre and Wally B. [34]. Reeves and address these tasks. -

Visualization in Multiobjective Optimization

Final version Visualization in Multiobjective Optimization Bogdan Filipič Tea Tušar Tutorial slides are available at CEC Tutorial, Donostia - San Sebastián, June 5, 2017 http://dis.ijs.si/tea/research.htm Computational Intelligence Group Department of Intelligent Systems Jožef Stefan Institute Ljubljana, Slovenia 2 Contents Introduction A taxonomy of visualization methods Visualizing single approximation sets Introduction Visualizing repeated approximation sets Summary References 3 Introduction Introduction Multiobjective optimization problem Visualization in multiobjective optimization Minimize Useful for different purposes [14] f: X ! F • Analysis of solutions and solution sets f:(x ;:::; x ) 7! (f (x ;:::; x );:::; f (x ;:::; x )) 1 n 1 1 n m 1 n • Decision support in interactive optimization • Analysis of algorithm performance • X is an n-dimensional decision space ⊆ Rm ≥ • F is an m-dimensional objective space (m 2) Visualizing solution sets in the decision space • Problem-specific ! Conflicting objectives a set of optimal solutions • If X ⊆ Rm, any method for visualizing multidimensional • Pareto set in the decision space solutions can be used • Pareto front in the objective space • Not the focus of this tutorial 4 5 Introduction Introduction Visualization can be hard even in 2-D Stochastic optimization algorithms Visualizing solution sets in the objective space • Single run ! single approximation set • Interested in sets of mutually nondominated solutions called ! approximation sets • Multiple runs multiple approximation sets • Different -

Inviwo — a Visualization System with Usage Abstraction Levels

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON VISUALIZATION AND COMPUTER GRAPHICS, VOL X, NO. Y, MAY 2019 1 Inviwo — A Visualization System with Usage Abstraction Levels Daniel Jonsson,¨ Peter Steneteg, Erik Sunden,´ Rickard Englund, Sathish Kottravel, Martin Falk, Member, IEEE, Anders Ynnerman, Ingrid Hotz, and Timo Ropinski Member, IEEE, Abstract—The complexity of today’s visualization applications demands specific visualization systems tailored for the development of these applications. Frequently, such systems utilize levels of abstraction to improve the application development process, for instance by providing a data flow network editor. Unfortunately, these abstractions result in several issues, which need to be circumvented through an abstraction-centered system design. Often, a high level of abstraction hides low level details, which makes it difficult to directly access the underlying computing platform, which would be important to achieve an optimal performance. Therefore, we propose a layer structure developed for modern and sustainable visualization systems allowing developers to interact with all contained abstraction levels. We refer to this interaction capabilities as usage abstraction levels, since we target application developers with various levels of experience. We formulate the requirements for such a system, derive the desired architecture, and present how the concepts have been exemplary realized within the Inviwo visualization system. Furthermore, we address several specific challenges that arise during the realization of such a layered architecture, such as communication between different computing platforms, performance centered encapsulation, as well as layer-independent development by supporting cross layer documentation and debugging capabilities. Index Terms—Visualization systems, data visualization, visual analytics, data analysis, computer graphics, image processing. F 1 INTRODUCTION The field of visualization is maturing, and a shift can be employing different layers of abstraction. -

A Very Simple Approach for 3-D to 2-D Mapping

Image Processing & Communications, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 75-82 75 A VERY SIMPLE APPROACH FOR 3-D TO 2-D MAPPING SANDIPAN DEY (1), AJITH ABRAHAM (2),SUGATA SANYAL (3) (1) Anshin Soft ware Pvt. Ltd. INFINITY, Tower - II, 10th Floor, Plot No.- 43. Block - GP, Salt Lake Electronics Complex, Sector - V, Kolkata - 700091 email: [email protected] (2) IITA Professorship Program, School of Computer Science, Yonsei University, 134 Shinchon-dong, Sudaemoon-ku, Seoul 120-749, Republic of Korea email: [email protected] (3) School of Technology & Computer Science Tata Institute of Fundamental Research Homi Bhabha Road, Mumbai - 400005, INDIA email: [email protected] Abstract. libraries with any kind of system is often a tough trial. This article presents a very simple method of Many times we need to plot 3-D functions e.g., in mapping from 3-D to 2-D, that is free from any com- many scientific experiments. To plot this 3-D func- plex pre-operation, also it will work with any graph- tions on 2-D screen it requires some kind of map- ics system where we have some primitive 2-D graph- ping. Though OpenGL, DirectX etc 3-D rendering ics function. Also we discuss the inverse transform libraries have made this job very simple, still these and how to do basic computer graphics transforma- libraries come with many complex pre-operations tions using our coordinate mapping system. that are simply not intended, also to integrate these 76 S. Dey, A. Abraham, S. Sanyal 1 Introduction 2 Proposed approach We have a pictorial representation (Fig.1) of our 3-D to 2-D mapping system: We have a function f : R2 → R, and our intention is to draw the function in 2-D plane. -

The New Plot to Hijack GIS and Mapping

The New Plot to Hijack GIS and Mapping A bill recently introduced in the U.S. Senate could effectively exclude everyone but licensed architects, engineers, and surveyors from federal government contracts for GIS and mapping services of all kinds – not just those services traditionally provided by surveyors. The Geospatial Data Act (GDA) of 2017 (S.1253) would set up a system of exclusionary procurement that would prevent most companies and organizations in the dynamic and rapidly growing GIS and mapping sector from receiving federal contracts for a very-wide range of activities, including GPS field data collection, GIS, internet mapping, geospatial analysis, location based services, remote sensing, academic research involving maps, and digital or manual map making or cartography of almost any type. Not only would this bill limit competition, innovation and free-market approaches for a crucial high-growth information technology (IT) sector of the U.S. economy, it also would cripple the current vibrant GIS industry and damage U.S. geographic information science, research capacity, and competitiveness. The proposed bill would also shackle government agencies, all of which depend upon the productivity, talent, scientific and technical skills, and the creativity and innovation that characterize the vast majority of the existing GIS and mapping workforce. The GDA bill focuses on a 1972 federal procurement law called the Brooks Act that reasonably limits federal contracts for specific, traditional architectural and engineering services to licensed A&E firms. We have no problem with that. However, if S.1253 were enacted, the purpose of the Brooks Act would be radically altered and its scope dramatically expanded by also including all mapping and GIS services as “A&E services” which would henceforth would be required to be procured under the exclusionary Brooks Act (accessible only to A&E firms) to the great detriment of the huge existing GIS IT sector and all other related companies and organizations which have long been engaged in cutting-edge GIS and mapping. -

Basic Science: Understanding Numbers

Document name: How to use infogr.am Document date: 2015 Copyright information: Content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence OpenLearn Study Unit: BASIC SCIENCE: UNDERSTANDING NUMBERS OpenLearn url: http://www.open.edu/openlearn/science-maths-technology/basic-science-understanding-numbers/content-section-overview Basic Science: Understanding Numbers Simon Kelly www.open.edu/openlearn 1 Basic Science: Understanding Numbers A guide to using infogr.am Infographics are friendly looking images and graphs which convey important information. In the past an infographic was the result of a long and painful process between designers and statisticians involving numerous meetings, data management and testing of designs and colour schemes. Nowadays they are much simpler to create. In fact, the company infogr.am has created a website that simplifies this process so that anyone can do it. The guidance below outlines a few simple instructions on how to use infogr.am to create the types of graphs discussed in this course. We will be using the data from the ‘Rainfall data PDF’. You should download the PDF before you start. Remember, you do not need to plot all the graph types or all the data. Simply pick two countries and compare their rainfall. This is a basic guide to Infogr.am; the site can do much more than what we describe below, so have a play and see what you find out! 1. Go to https://infogr.am/. 2. Select ‘Sign up now’ and create a username, enter your email address and choose a password (if you prefer, you can use your Facebook, Twitter or Google+ account to connect and log in). -

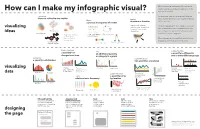

How Can I Make My Infographic Visual? Topic You’Ve Selected

When authoring an infographic, it is important to explore your data and ideas to make sense of the How can I make my infographic visual? topic you’ve selected. Explore how Visualizing can help you make sense of data and ideas are related to one another Explore ideas, and the following are some powerful ways to Explore structure or function explore your topic. a process or sequence of events Images with callouts, Once you’ve explored through visualizing, you will photographs, anatomical visualizing want to select some of the visualizations that best drawings, or scientific Tree diagram communicate what you believe is important, and ideas 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 illustrations Venn Diagram 2 include them in your infographic. Progressive depth or Timeline of related Cyclical diagram scale, image at historical events different levels of Ways of designing the overall look and feel of your magnification 3 infographic are included in the final section. Concept map or Branching Flowchart 1 network diagram Linear flowchart Explore if and how Add Explore if and how a quantity has an additional quantity a quantity is different in changed over time or category to a graph two or more different groups Explore how 3500 3500 60 Explore if and how 3000 50 3000 60 a quantity is distributed 40 50 2500 2500 30 40 two quantities are related 2000 30 2000 20 20 1500 10 1500 10 0 1000 0 1000 60 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 0 50 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 40 30 Timeline 3500 visualizing Timeline Dot Plot Bubble chart 20 Multiple -

Which Chart Or Graph Is Right for You? Tell Impactful Stories with Data

Which chart or graph is right for you? Tell impactful stories with data Authors: Maila Hardin, Daniel Hom, Ross Perez, & Lori Williams January 2012 p2 You’ve got data and you’ve got questions. Creating a Interact with your data chart or graph links the two, but sometimes you’re not sure which type of chart will get the answer you seek. Once you see your data in a visualization, it inherently leads to more questions. Your bar graph reveals that This paper answers questions about how to select the sales tanked in the second quarter in the Southeast. best charts for the type of data you’re analyzing and the A scatter plot shows an unexpected concentration of questions you want to answer. But it won’t stop there. product defects in one category. Donations from older Stranding your data in isolated, static graphs limits the alumni are significantly down according to a heat map. number of questions you can answer. Let your data In each example, your reaction is the same: why? become the centerpiece of decision making by using it Equip yourself to answer these questions by making to tell a story. Combine related charts. Add a map. your visualization interactive. Doing so creates the Provide filters to dig deeper. The impact? Business opportunity for you and others to analyze your data insight and answers to questions at the speed of visually and in real-time, letting you answer questions Which chart or graph is right for you? Tell impactful stories with data Tell Which chart or graph is right for you? thought. -

Data Visualization Options in Insights

Change: process through which something becomes Distribution: the arrangement of phenomena, could be different, often over time numerically or spatially A bar graph uses either horizontal or vertical bars to show Histograms show the distribution of a numeric variable. Data type: Qualitative Quantitative Temporal comparisons among categories. They are valuable to The bar represents the range of the class bin with the identify broad differences between categories at a glance. height showing the number of data points in the class bin. Measure: ascertain the size, amount, or degree of (something) A heat chart shows total frequency in a matrix. Using a A box plot displays data distribution showing the median, temporal axis values, each cell of the rectangular grid are upper and lower quartiles, min and max values and, outliers. A bar graph uses either horizontal or vertical bars to show symbolized into classes over time. Distributions between many groups can be compared. comparisons among categories. They are valuable to identify broad differences between categories at a glance. Bubble charts with three numeric variables are multivariate A choropleth map allows quantitative values to be mapped charts that show the relationship between two values while by area. They should show normalized values not counts A treemap shows both the hierarchical data as a proportion a third value is shown by the circle area. collected over unequal areas or populations. of a whole and, the structure of data. The proportion of categories can easily be compared by their size. Graduated symbol maps show a quantitative difference Graduated symbol maps show a quantitative difference between mapped features by varying symbol size. -

Cartography in Children's Literature. PUB DATE 96 NOTE 4P.; In: Sustaining the Vision

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 400 859 IR 056 174 AUTHOR Ranson, Clare TITLE Cartography in Children's Literature. PUB DATE 96 NOTE 4p.; In: Sustaining the Vision. Selected Papers from the Annual Conference of the International Association of School Librarianship (24th, Worcester, England, July 17-21, 1995); see IR 056 149. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.) (120) Speeches /Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PCO1 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cartography; *Childrens Literature; Fantasy; Fiction; Foreign Countries; Graphic Arts; *Illustrations; Locational Skills (Social Studies); *Maps; Map Skills; Visual Aids ABSTRACT Maps have been used as an illustrative device in children's books for a long time; however, they are an area of illustration that has been largely ignored by critics. Maps are most commonly used as frontispiece illustrations in adventure and fantasy books. They have also generally been aimed at the male reader when children's books were marketed separately for boys and girls. A good map will complement the text and internal illustrations and add another visual level to the text. Children are now less skilled in cartographic recognition, due to geography being taught differently than it was in the past. Maps in children's books can be divided into three groups: (1) maps which depict a real place; (2) fantasy maps which have no basis in reality and are the creation of the author and cartographer; and (3) maps which combine both reality and fantasy--when the map shows an area that is real but has been altered to fit the plot. Maps in selected children's books are described and discussed to show how maps are a branch of illustration worthy of critical attention. -

Communicating Through Infographics: Visualizing Scientific and Engineering Information

Communicating through infographics: visualizing scientific and engineering information Christa Kelleher Department of Earth and Ocean Sciences Nicholas School of the Environment Duke University hp://xkcd.com/688/ 1 Model diagnostics, catchment modeling, and visualization of large environmental datasets [Kelleher et al., 2012; Kelleher et al., 2013; Sawicz et al., 2013; Kelleher et al., in prep] 2 The importance of How much data is created every minute? visualization As of 2012 …. • 100,000 tweets • 2,000,000 google search queries • 47,000 app downloads • 571 new websites • 217 new mobile web users 3 Source: [Visual News, hp://www.visualnews.com/2012/06/19/how-much-data-created-every-minute/?view=infographic] The importance of How much data is created every minute? visualization 4 Source: [Mashable, hp://mashable.com/2014/04/23/data-online-every-minute/?] Resources Data analysis: Matlab R, Python Spaal analysis: ArcGIS R Mapping packages, qGIS, GRASS GIS, SAGA Fine tuning: Illustrator Inkscape, CorelDRAW 5 HOW DO WE CREATE EFFECTIVE VISUALIZATIONS? 6 Rule 1 Choose an effective plot type The type of plot you use should compliment the type of data you have (and the message you are conveying) [Source: Matlab, http://www.mathworks.com/help/matlab/creating_plots/figures-plots-and-graphs.html] 7 Rule 1 Choose an effective plot type Plots use attributes to ‘encode’ information… …BUT our ability to quantitatively perceive these attributes differs! 8 [Kelleher and Wagner (2011); Few (2009)] Posion Common Non-aligned Length Details Direcon Angle -

Chapter 2 – Part 2 Multiview Drawing Chapter Objectives

Chapter 2 – Part 2 Multiview Drawing Chapter Objectives •Explain what multiview drawings are and their importance to the field of technical drawing. •Explain how views are chosen and aligned in a multiview drawing. •Visualize and interpret the multiviews of an object. •Describe projection planes •Describe normal, inclined and oblique surfaces •Describe line types •Describe line weights •Interpret the multiviews of graphic primitives •Describe orthographic projection including the miter line technique Supplemental Files •Describe the line types and line weights used in technical drawings as defined by the ASME Y14.2M standard. •Explain the difference between drawings created with First Angle and Third Angle projection techniques. •Use a miter line to project information between top and side views. •Create multiview sketches of objects including the correct placement and depiction of visible, hidden and center lines. Supplemental files are available for download inside the Chapter 2 folder of the book’s file downloads. Please see the inside front cover for further details. © Technical Drawing 101 with AutoCAD Smith & Ramirez – All rights reserved. 2.4 MULTIVIEW DRAWINGS Multiview drawing is a technique used by drafters and designers to depict a three-dimensional object (an object having height, width and depth) as a group of related two-dimensional (having only width and height, or width and depth) views. A person trained in interpreting multiview drawings, can visualize an object’s three-dimensional shape by studying the two-dimensional multiview drawings of the object. For example, Figure 2.15 provides a three-dimensional (3D) image of a school bus, and while a 3D view of the bus is very helpful in visualizing its overall shape, it doesn’t show the viewer all of the sides of the bus, or the true length, width, or height of the bus.