Setting up and Running a Small Meat Or Fish Processing Enterprise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meat and Muscle Biology™ Introduction

Published June 7, 2018 Meat and Muscle Biology™ Meat Science Lexicon* Dennis L. Seman1, Dustin D. Boler2, C. Chad Carr3, Michael E. Dikeman4, Casey M. Owens5, Jimmy T. Keeton6, T. Dean Pringle7, Jeffrey J. Sindelar1, Dale R. Woerner8, Amilton S. de Mello9 and Thomas H. Powell10 1University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, USA 2University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801, USA 3University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA 4Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506, USA 5University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701, USA 6Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA 7University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA 8Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA 9University of Nevada, Reno, NV, 89557, USA 10American Meat Science Association, Champaign, IL 61820, USA *Inquiries should be sent to: [email protected] Abstract: The American Meat Science Association (AMSA) became aware of the need to develop a Meat Science Lexi- con for the standardization of various terms used in meat sciences that have been adopted by researchers in allied fields, culinary arts, journalists, health professionals, nutritionists, regulatory authorities, and consumers. Two primary catego- ries of terms were considered. The first regarding definitions of meat including related terms, e.g., “red” and “white” meat. The second regarding terms describing the processing of meat. In general, meat is defined as skeletal muscle and associated tissues derived from mammals as well as avian and aquatic species. The associated terms, especially “red” and “white” meat have been a continual source of confusion to classify meats for dietary recommendations, communicate nutrition policy, and provide medical advice, but were originally not intended for those purposes. -

Wisconsin” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 13, folder “4/4-5/76 - Wisconsin” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Betty Ford donated to the United States of America her copyrights in all of her unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON April 2, 1976 MEMORANDUM FOR: MRS. FORD VIA: RED CAVANEY FROM: PETER SORUM SUBJECT: YOUR VISIT TO WISCONSIN Sunday & Monday, April 4-5, 1976 Attached at TAB A is the Proposed Schedule for the subject event. APPROVE DISAPPROVE BACKGROUND Your trip to Wisconsin is essentially a campaign tour which begins with an airport greeting from the Grand Rapids Friends of the First Family. At the Edgewater Hotel, you will present plaques to Madison area participants in the 1976 Winter Olympics at ceremonies sponsored by the Greater Madison Chamber of Commerce and attend a brief, private reception for Wisconsin PFC Leadership. On Monday you will fly to Milwaukee to visit Marquette University Campus and see a Chapel built in the 15th Century that was moved, brick by brick from France to the Campus. -

Oktoberfest-2018-Menu.Pdf

APPETIZERS & SOUPS LIVER DUMPLING OR GOULASH SOUP CUP 5 BOWL 7 JAUSEN PLATTE 18 (Serves 2) POTATO PANCAKES 8 Assortment of cured meats, farmer style cheeses Four of our famous homemade potato and imported pates accompanied by gherkins potato pancakes, served with and baguette toasts with applesauce and sour cream HACKEPETER 13 OKTOBERFEST PRETZEL 8 Freshly ground top sirloin with onions, capers, Served with a Stella Artois gouda cheese mustard, paprika and egg yolk served with rye bread dip and sweet and spicy honey mustard SAUSAGE SAMPLER 11 Bratwurst, thüringer, and cheese knackwurst sausages served with german mustards and a side of sauerkraut and pickled red cabbage ENTREES All entrees come with soup of the day Substitute soup of the day for house salad +$2, Goulash Soup or Liver Dumpling Soup +$3 EDELWEISS PLATTER 25 A sampler platter for all tastes! Includes Rinsrouladen, Pork Schnitzel, Kassler, Bratwurst and Roast Pork Loin served with German fries, red cabbage, sauerkraut and spatzle BAYERISCHER SCHWEINSHAXE (allow 25-30min) 27 Our famous three pound pork shank baked to crispy perfection and served atop our bock beer sauce; choice of three sides SCHNITZEL SAMPLER 21 A sampling of our rahm, jaeger and gyspy schnitzels; choice of two sides BAVARIAN BEER ROASTED PORK 21 Tender, juicy pork perfectly roasted in a Bavarian beer sauce with crispy top; choice of two sides PORK GOULASH 19 Tender pork in a paprika sauce; choice of two sides BEEF STROGANOFF 22 Tender beef served over pappardelle noodles in a rich sherry cream gravy with -

Deutsche Nacht at Field to Fork

Deutsche Nacht at Field to Fork Friday, January 29th 5-10pm Dine-in, Takeout, & Curbside Available Advance Takeout Orders Encouraged (920) 694-0322 Gemischter Salat greens, ham, carrots, cucumber, radish, cherry tomato, dinklebrot croutons, creme fraiche with a herb dressing $12 Buckwheat Dumpling Soup smoked pork jowl, apple, and cabbage $9 Pierogi german style pierogi stuffed with potato, onion, cheese, summer sausage, with a beer-apple house mustard sauce $12 Wurstwaren sample platter of mixed cured meats; Mettwurst, Braunschweiger, Summer Sausage, with cheese, dinkelbrot, and house mustard $18 Lange Rote Thüringer sausage, onion, and mustard on a house bun with fries $13 Spätzle carmalized onion, cheese, and speck $17 Sausage Plate Bockwurst & Weisswurst sausage, braised red cabbage, German potato salad, house sauerkraut, and mustard $21 Pork Schnitzel lightly breaded and fried pork cutlet, mushroom gravy, German potato salad, house sauerkraut, and braised red cabbage $24 Drinks (To Go!) Old Fashioned - $8 Freising Beer - $5/glass or $18/32oz Growler ‘Underberg’ digestif - $4 Deutsche Nacht at Field to Fork Friday, January 29th 5-10pm Dine-in, Takeout, & Curbside Available Advance Takeout Orders Encouraged (920) 694-0322 Sausage Guide Mettwurst beef, veal, pork, coriander, celery seed, allspice, marjoram, caraway, mustard seed Bierwurst beef, pork, cardamom, coriander, paprika, dark beer, salt, pepper, mustard seed Braunschweiger pork jowl, pork liver, pork fat, salt, onion, pepper, clove, allspice, sage, marjoram, nutmeg, ginger Weisswurst pork, veal, mace, ginger, lemon zest, parsley Thüringer pork, veal, caraway, mace, garlic Knackwurst smoked pork, veal, mace, paprika, coriander, allspice Bockwurst pork, veal, onion, clove, milk, egg. -

Appetizers German Specialty Dinners

Appetizers Nuernberger Bratwurst - four grilled Nuernberger brats $4.50 German style meatballs - six meatballs in brown gravy $4.50 Side salad with house dressing $3.50 German Specialty Dinners Schnitzel Dinner - pork schnitzel served with home fries and cabbage $14.95 Lemon Schnitzel Dinner - natural schnitzel pan sautéed in lemon sauce served with home fries and red cabbage $13.95 Jagerschnitzel - breaded pork schnitzel topped with mushroom sauce served with home fries and red cabbage $15.95 Wiener Schnitzel - veal cutlet, thin, lightly breaded and fried $17.95 Bouletten - German style hamburger steak dinner served with home fries and red cabbage $12.95 Grilled Kassler Rippchen - smoked pork chop served potato salad and sauerkraut. Served with one or two pork chops $12.95/$17.95 Leberkase - liver/ham loaf, grilled and served with home fries and red cabbage $8.50 Dinner for Two - four sausages (chefs choice), one kassler rippchen, home fries, red cabbage, German potato salad and sauerkraut $30.95 Prices subject to change without notice German Sausage Platters all the following platters are served with German potato salad and our special sauerkraut and bread German Wiener Dinner $8.50 Grilled Bratwurst Dinner $12.95 Grilled Smoked Bratwurst Dinner $12.95 Grilled Bauernwurst Dinner $12.95 Knackwurst Dinner $12.95 Grilled Hungarian Kolbase Dinner $12.95 Grilled Nuernberger Bratwurst Dinner $12.95 Grilled Weisswurst Dinner (veal sausage) $12.95 Grilled hot and spicy Bratwurst Dinner $12.95 Grilled Andouille Sausage platter (Cajun spiced) -

Proudly Serving South Australian Local Produce

SPARKLING & CHAMPAGNE SPOONY BEER Angas Brut Premium Cuvée $6.50 $28.00 Hahn Light $7.50 South Australia Coopers Pale $7.90 Mollydooker Girl on The Go Coopers Sparkling $7.90 Sparkling McLaren Vale SA $29.00 West End $7.90 Corona $7.90 Louis Auger Peroni $7.90 Brut Champagne France $55.00 German Beer $9.90 (Ask our friendly staff) WHITE WINE Oxford Landing Estates ADELAIDE HILLS BEERS & CIDERS Sauvignon Blanc SA $6.50 $29.00 Hills Apple or Pear Cider $8.90 Prancing Pony Pale Ale $8.90 Yalumba Y Series Prancing Pony India Red Ale $9.90 Sauvignon Blanc SA $7.50 $34.00 Prancing Pony Sunshine Ale $9.90 Yalumba Y Series Chardonnay SA $7.50 $34.00 SPOONY SPIRITS Adelaide Hills Pinot Gris SA $7.50 $34.00 Jack Daniels, Johnnie Walker Black, Gordon’s Gin, Bundaberg, Bacardi, Wine of the Month Ask our friendly staff Smirnoff, Pimm’s No 1 $7.50 ROSÉ & MOSCATO Glenlivet Single Malt, Bombay Sapphire, Kraken Dark Rum, Absolute, Angas Moscato SA $7.00 $29.00 Canadian Club, James Jameson $9.00 Banrock Station Rosé SA $7.00 $29.00 SOFT DRINKS RED WINES Spring Water 600ml $3.90 Oxford Landing Estates Sparkling Water 330ml $4.50 Shiraz SA $6.50 $29.00 750ml $6.50 Elephant In The Room Pinot Noir NSW $7.50 $34.00 1 Litre $7.90 Yalumba Y Series Shiraz SA $7.50 $34.00 Coke, Coke No Sugar, Glass $4.50 Mollydooker Boxer Fanta, Sprite, Lift Jug $8.90 Shiraz McLaren Vale SA $42.00 Lemon Lime Bitters / Glass $5.50 Yalumba Y Series Soda Lime Bitters Jug $9.50 Cabernet Sauvignon SA $7.50 $34.00 Smith & Hooper Orange juice/ Apple Juice/ Glass $4.90 Cabernet Sauvignon -

Food Service & Retail

FOOD SERVICE & RETAIL PRODUCT GUIDE E.1 | 2018 SAUSAGE THAT LINKS PEOPLE TOGETHER® Klement’s Sausage is made with the highest quality meats and spices in small batches to ensure consistent, great taste every time. We pride ourselves in the finest Old World flavors crafted from authentic European recipes passed down for generations. Our wide variety of products are great anytime for any occasion. BULK SAUSAGE Bulk Fresh Sausage Code Description Box Pack Code Description Box Pack 4433 Polish 3-1, 9˝ 4/2.5# 10 lb 4620 Italian Rope Frozen 10 lb 4380 Italian Frozen 4-1, 6˝ 4/2.5# 10 lb 4721 Brat Patty 4-1 IQF 4/2.5# 10 lb 4610 Brat Frozen Bulk 4-1, 6˝ 4/2.5# 10 lb Smoked/Cooked Bulk Natural Casing Sausage Code Description Box Pack Code Description Box Pack 5070 Smoked Andouille Rope 12 lb 5886 Backyard Selects® Cooked Italian 5-1, 5.5˝ 10 lb 5390 Old Fashioned Wieners 8-1, 5.5˝ 10 lb 5450 Cooked Italian 5-1, 5.5˝ 10 lb 5500 Sheep Casing Wieners 8-1, 5.5˝ 10 lb 5451 Cooked Italian 4-1, 6˝ 10 lb 5402 Knackwurst 4-1, 4.5˝ 10 lb 5453 Cooked Italian 3-1, 7˝w 10 lb 5430 Smoked Kielbasa 2-1, 9˝ 10 lb 5468 Cooked Italian Hot 3-1, 7˝ 10 lb 5440 Hot Beef Polish 5-1, 5.5˝ 10 lb 5860 Cooked Coarse Brat 4-1, 6˝ 10 lb 5490 Smoked Polish 4-1, 6˝ 10 lb 5850 Cooked Coarse Brat 5-1, 5.5˝ 10 lb 5510 Smoked Polish 5-1, 5.5˝ 10 lb 5867 Backyard Selects® Cooked Bratwurst 5-1, 5.5˝ 10 lb 5432 Smoked Polish 3-1, 9˝ 10 lb 5853 Cooked Brat Coarse 3-1, 7˝ 10 lb 5800 Smoked Brat 5-1, 5.5˝ 10 lb 5857 Cooked Brat Coarse 3-1, 9˝ 10 lb 5950 Smoked Brat 4-1, 6˝ 10 lb 5474 -

WIBERG Corporation PRODUCT LIST Effective: January 1, 2011 BLENDED PRODUCTS - SAUSAGES SMOKED AND/OR COOKED

WIBERG Corporation PRODUCT LIST Effective: January 1, 2011 BLENDED PRODUCTS - SAUSAGES SMOKED AND/OR COOKED DESCRIPTION DESCRIPTION ALPENWURST FRANKFURTER - SPECIAL ANDOUILLE FRANKFURTER - SUPER AUFSCHNITT GARLIC BACON GARLIC & CHEESE BACON CHEDDAR GELBWURST BANGER GOETTINGER BARESSE GRISSWUERTEL BEER HAM BIERSCHINKEN HAM - BEER BIERWURST HAM - NIAGARA BLOOD HAUSMACHER LEBERWURST BOCKWURST HEADCHEESE BOEREWORS HOT DOG BOLOGNA HUNGARIAN BRATWURST HUNTER BRATWURST - BAUERN (FARMER) ITALIAN BRATWURST - BEER JAGDWURST BRATWURST - COARSE KABANOSSY BRATWURST - FINE KALBLEBERWURST BRATWURST - GERMAN KANTWURST BRATWURST - NUERNBERG KNACKER BRATWURST - OCTOBER STYLE KNACKER - EXTRA FINE BRATWURST - ROAST KNACKWURST BRATWURST - ROAST - FLAX SEED KOLBASSA BRATWURST - ROAST GARLIC KOLBASSA - HAM BRATWURST - THUERINGER KOREAN BBQ BRAUNSCHWEIGER KRAKAUER BREAKFAST LANDJAGER BREAKFAST - REDUCED SODIUM LINGUICA CAPICOLLA LUNCHEON MEAT CEVAPCICI LYONER CHABAY MEATLOAF CHORIZO MEATLOAF - BAVARIAN CHORIZO & LONGANIZA MENNONITE COCKTAIL SAUSAGES MERGUEZ DEBRECZINER METTWURST DEBRECZINER - CHABAY METTWURST - ONION DOMACA METTWURST - WESTFALIAN DUTCH ROOKWURST MEUNCHNER WIESSWURST EL PASTOR MORTADELLA EXTRAWURST KOENGLICH OCTOBERFEST FARMER PEPPERWURST FLEISCHWURST POLISH We can make a seasoning, or we can add binder and/or cure to make a complete easy to use unit! WIBERG Corporation PRODUCT LIST Effective: January 1, 2011 BLENDED PRODUCTS - SAUSAGES SMOKED AND/OR COOKED DESCRIPTION DESCRIPTION PORCHETTA PRESSWURST RUEGENWALDER TEEWURST SAHNELEBERWURST SCHINKENSPECK SCHINKENWURST SCHLACKWURST SEJ - WITH ONION SMOKIE - BAVARIAN SREMSKA - HOT SREMSKA - SWEET SUJUK - HOT SUJUK - MILD SUJUK - TURKISH SULMTALER KRAINER SUMMER THURINGER ROTTWURST TONGUE TYROLER WEINER WEINER - CONEY ISLAND WEINER - REDUCED SODIUM WEINER - TOFU WIESSWURST WIESSWURST - MUENCHNER ZWIEBELMETTWURST We can make a seasoning, or we can add binder and/or cure to make a complete easy to use unit! . -

Oktoberfest 2015 Dinner Menu Executive Chef Chas Grossman and Team

Oktoberfest 2015 Dinner Menu Executive Chef Chas Grossman and team Appetizers *Wild Mushroom Crepes – three crepes, filled with wild mushrooms & parmesan cheese, topped with a white wine cream sauce $8 *Baked Brie topped with a pecan port cranberry glaze, served with fruit and bread $9 Trio of Sausages – grilled Patak fingerlink knackwurst, bratwurst and kielbasa sausages on a bed of homemade sauerkraut, served with a pretzel & whole grain mustard Regular size $9 “For sharing at the table” $16 *Oven Baked Soft Pretzels – served with beer cheese dip & honey whole grain mustard $9 City Café Crab Cake – lump crab cake, sautéed golden brown and served with creamy grain mustard Remoulade $9 Salads * House Salad – mixed baby greens, with cucumbers, carrots & fresh tomatoes $6 * Café Caesar Salad – romaine hearts, tossed with a classic caesar dressing, parmesan cheese and croutons $7 Add to above salads: grilled or blackened: Chicken OR Salmon $5 Kale & Grilled Chicken OR Grilled Salmon Chopped Salad – grilled chicken breast tossed with fresh kale, grapes, dried cranberries, candied pecans, goat cheese and champagne vinaigrette $11 Soups Goulash Soup Soup of the Day Cup $3 Bowl $5 Cup $3 Bowl $5 Small House Salad with Entree Small Caesar Salad with Entree $3 $3 City Café German Entrées Classic Wiener Schnitzel – pan-fried, breaded veal cutlet, garnished with fresh lemon, served with mashed potatoes and vegetables $14 Jäger Schnitzel – pan-fried, breaded veal cutlet, topped with a red wine mushroom sauce, served with mashed potatoes and vegetables -

List of Sausages Intensity Milk Pork Garlic Type

List of sausages Intensity Milk Pork Garlic Type 5 PEPPERS Raw Meat Pork and five different types of peppers ACAPULCO Smoked Pork, veal and beef, hot peppers APPLE AND BACON Raw Meat Porc, apple and bacon APPLE CRANBERRY AND CINNAMON Raw Meat Pork sausage with a mix of apples cranberries with a touch of cinnamon AUSTRIAN Smoked Pork, veal, beef, cheddar and asparagus BEER (GLUTENBERG RED) Raw Meat Pork and beer BISON Raw Meat Bison and porc BISON, DARK CHOCOLATE AND PORT Raw Meat Bison and pork, avec with 70% dark chocolate and Port BLUE CHEESE Raw Meat Pork stuffed with blue cheese BOAR BLUEBERRIES AND ICE CIDER Raw Meat Boar and pork sausage mixed with blueberries and a touch of ice cider BOAR GUINNESS AND PEPPER Raw Meat Boar and pork with Guiness beer and pepper (CONTAINS GLUTEN) BREAKFAST SAUSAGE Raw Meat Pork, beef with a touch of sage BROCCOLI AND CHEDDAR Raw Meat Broccoli and cheddar pork sausage BUTTER CHICKEN - LOW SODIUM Raw Meat Poulet au beurre CAJUN CHICKEN - LOW SODIUM Raw Meat Chicken with cajun spices CAMPAGNARDE Smoked Pork, veal, beef, pepper and garlic CAULIFLOWER, CHEDDAR AND BACON Raw Meat Pork, cauliflower, cheddar and bacon CHEDDAR AND BACON Smoked Pork, veal, beef and cheddar bacon CHEESE AND MUSHROOMS Raw Meat Pork, mushrooms and mozzarella CHIPOLATA Raw Meat Pork, chive, sage and nutmeg CHORIZO Raw Meat Pork, spanish spices CURRY Raw Meat Pork and curry CURRY AND MUSHROOMS Raw Meat Pork, curry and mushrooms DEER AND RED WINE Raw Meat Deer and red wine DUCK PROVENÇAL Raw Meat Duck with provençal herbs of southern -

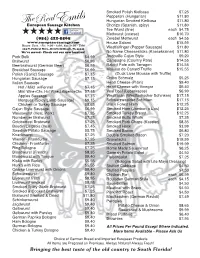

Emils-Menu-10-2018.Pdf

Smoked Polish Kielbasa $7.25 Pepperoni (Hungarian) $11.80 Hungarian Smoked Kielbasa $11.80 European Sausage Kitchen Chorizo (Spanish, spicy) $11.80 Tee Wurst (fine) each $4.75 HHHHH Mettwurst (coarse) $10.70 (954) 422-5565 Zwiebel Mettwurst each $4.55 www.european-sausage.com House Salami $15.99 Hours: Tues. - Fri. 9:00 - 6:00, Sat. 9:00 - 5:00 124 N. Federal Hwy., Deerfield Beach, FL 33441 Westfalfinger (Pepper Sausage) $11.80 We’ve moved - Check out our new location! No Name Cheesesticks (Kaesekrainer) $11.80 Pork Bulk $4.99 Andouille Cajun Style $9.20 Bratwurst $6.99 Campagne (Country Pate) $14.55 Beerbratwurst (German Beer) $6.99 Rabbit Pate with Tarragon $14.55 Breakfast Sausage $6.99 Mousse de Canard Truffle $15.55 Polish (Garlic) Sausage $7.15 (Duck Liver Mousse with Truffle) Hungarian Sausage $7.15 Onion Schmalz $5.25 Italian Sausage Head Cheese (Plain) $9.40 Hot / Mild w/Fennel $7.15 Head Cheese with Vinegar $9.40 Mild: Wine+Chs. Hot:Wine,Jalapeno+Chs. $7.15 Veal Loaf (Leberkaese) $6.99 Apples Sausage $7.15 Westfalian (Westfaelischer Schinken) $17.15 Merguez (Spicy Lamb Sausage) $9.15 Schwarzwaelder Schinken $17.15 Chicken or Turkey Sausage $8.65 Black Forest Ham $12.25 Cajun Style Sausage $6.99 Smoked Ham (Jambon a L’os) $12.25 Weisswurst (Veal, Pork) $7.25 Smoked Turkey Breast $12.25 Nurnberger Bratwurst $7.25 Smoked Butts Whole $7.35 Octoberfest Bratwurst $7.25 Smoked Pork Chops (Kassler) $8.35 Boudin Liegeois (Veal) $7.45 Smoked Hock $3.99 Swedish Potato Sausage $5.75 Smoked Bacon $6.80 Knackwurst $7.25 Double Smoked Bacon -

Essen Haus German Restaurant Good Times, Good Food and Drink… We

ESSEN HAUS GERMAN RESTAURANT GOOD TIMES, GOOD FOOD AND DRINK… WE. SERVE. BIER. STARTERS JUMBO PRETZEL — $4 ELLSWORTH CHEESE CURDS — $9 A giant pretzel served with Haus mustard, cheese Wisconsin-made cheese curds, breaded and fried. sauce and sauerkraut dip. Served with chipotle ranch. PRETZELS & DIPS — $4 MEAT & CHEESE BOARD — $12 4 hot soft pretzels served with our signature hot and Assorted meats and cheeses served with rye bread sweet mustard and kraut & cream dipping sauces. and hot soft pretzels. KARTOFFELPUFFER — $9 FLAMMKUCHEN — $13 3 potato pancakes made with goat cheese and green Fresh-made 10” German pizza topped with creamy onion. Served with a side of applesauce. white sauce, caramelized onions, fresh herbs, corned beef and grated cheese. METERWURST PLATE — $10 A large smoked pork bratwurst served with a hot soft ARTICHOKE DIP — $11 pretzel, sauerkraut, Haus mustard, curry ketchup and Haus-made artichoke, cream cheese and spinach dip choice of French fries or German potato salad. served in a bread bowl with assorted veggies. HOT SAUSAGES & SAUERKRAUT — $10 CHICKEN WINGS (GFP*) — $10 Grilled weisswurst, knackwurst and thuringer Traditional bone-in chicken wings, breaded and fried. sausages, sliced and served on a bed of sauerkraut. Choose plain, BBQ, Buffalo or Nashville-style. Served Paired with Düsseldorf mustard and curry ketchup. with chipotle ranch or bleu cheese. GERMAN NACHOS — $10 STUFFED MUSHROOMS — $11 Crispy chips topped with diced sausage, haus-made Hearty mushrooms stuffed with crabmeat, cream sauerkraut, onions and grated cheddar & Swiss cheese and spicy Wisconsin cheddar. *Gluten-free. cheeses. MAIN ENTREES Unless noted, dinner selections are served with choice of potato (baked potato, German potato salad, German fried potatoes, French fries or spätzle noodles) and choice of vegetable (sauerkraut, red cabbage or veggie of the day).