4-Roman Pages 32-66

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47–410

no nonsense Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47–410 – interpretation ltd interpretation Contract number 1446 May 2011 no nonsense–interpretation ltd 27 Lyth Hill Road Bayston Hill Shrewsbury SY3 0EW www.nononsense-interpretation.co.uk Cadw would like to thank Richard Brewer, Research Keeper of Roman Archaeology, Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales, for his insight, help and support throughout the writing of this plan. Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47-410 Cadw 2011 no nonsense-interpretation ltd 2 Contents 1. Roman conquest, occupation and settlement of Wales AD 47410 .............................................. 5 1.1 Relationship to other plans under the HTP............................................................................. 5 1.2 Linking our Roman assets ....................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Sites not in Wales .................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Criteria for the selection of sites in this plan .......................................................................... 9 2. Why read this plan? ...................................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Aim what we want to achieve ........................................................................................... 10 2.2 Objectives............................................................................................................................. -

Medieval, Bibliography 22/12/2003

A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales Select Bibliography, Northeast Wales Medieval A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales East and Northeast Wales – Medieval, bibliography 22/12/2003 Adams. B. 1999. 'The Latin Epitaphs in Brecon Cathedral’. Brycheiniog 31. 31-42. Adams. M. 1988. Abbeycwmhir: a survey of the ruins. CPAT report 1. August 1988. Alban. J & Thomas. W S K. 1993. 'The charters of the borough of Brecon 1276- 1517’. Brycheiniog 25. 31-56. Alcock. L. 1961. 'Beili Bedw Farm. St Harmon’. Archaeology in Wales 1. 14-15. Alcock. L. 1962. 'St Harmon’. Archaeology in Wales 2. 18. Allcroft. A H. 1908. Earthwork of England. London. Anon. 1849. 'Account of Cwmhir Abbey. Radnorshire’. Archaeologia Cambrensis 4. 229-30. Anon. 1863. ‘Brut y Saeson (translation)’. Archaeologia Cambrensis 9. 59-67. Anon. 1884. ‘Inscription on a grave-stone in Llanwddyn churchyard’. Archaeologia Cambrensis 1. 245. Anon. 1884. 'Llanfechain. Montgomeryshire’. Archaeologia Cambrensis 1. 146. Anon. 1884. 'Nerquis. Flintshire’. Archaeologia Cambrensis 1. 247. Anon. 1884. ‘Oswestry. Ancient and Modern. and its Local Families’. Archaeologia Cambrensis 1. 193-224. Anon. 1884. 'Report of Meeting’. Archaeologia Cambrensis 1. 324-351. Anon. 1884. 'Restoration of Llanynys Church’. Archaeologia Cambrensis 1. 318. Anon. 1884. ‘Restoration of Meliden Church’. Archaeologia Cambrensis 1. 317-8. Anon. 1885. 'Review - Old Stone Crosses of the Vale of Clwyd and Neighbouring Parishes’. Archaeologia Cambrensis 6. 158-160. Anon. 1887. 'Report of the Denbigh meeting of the Cambrian Archaeological Association’. Archaeologia Cambrensis 4. 339. Anon. 1887. 'The Carmelite Priory. Denbigh’. Archaeologia Cambrensis 16. 260- 273. Anon. 1891. ‘Report of the Holywell Meeting’. -

Paper Information: Title: Aspects of Romanization in the Wroxeter

Paper Information: Title: Aspects of Romanization in the Wroxeter Hinterland Author(s): R. H. White and P. M. van Leusen Pages: 133–143 DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/TRAC1996_133_143 Publication Date: 11 April 1997 Volume Information: Meadows, K., Lemke, C., and Heron, J. (eds) 1997. TRAC 96: Proceedings of the Sixth Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference, Sheffield 1996. Oxford: Oxbow Books. Copyright and Hardcopy Editions: The following paper was originally published in print format by Oxbow Books for TRAC. Hard copy editions of this volume may still be available, and can be purchased direct from Oxbow at http://www.oxbowbooks.com. TRAC has now made this paper available as Open Access through an agreement with the publisher. Copyright remains with TRAC and the individual author(s), and all use or quotation of this paper and/or its contents must be acknowledged. This paper was released in digital Open Access format in April 2013. 15. Aspects of Romanization in the Wroxeter Hinterland by R. H. White & P. M. van Leusen Wroxeter's Paradox The common perception ofWroxeter is that it occupied an anomalous position as the fourth largest Roman town in Britain set within a landscape apparently practically devoid of any of the normal accoutrements of Romanized rural society (figure I). This creates a paradox in that, in all other Roman towns, there seems to be a direct relationship between the size of a town and the degree of Romanization in its hinterland. Ray Laurence has recently highlighted this perception in his study of Pompeii, concluding that " we cannot divide the city from the countryside, nor the countryside from the city. -

Roman Roads of Britain

Roman Roads of Britain A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Thu, 04 Jul 2013 02:32:02 UTC Contents Articles Roman roads in Britain 1 Ackling Dyke 9 Akeman Street 10 Cade's Road 11 Dere Street 13 Devil's Causeway 17 Ermin Street 20 Ermine Street 21 Fen Causeway 23 Fosse Way 24 Icknield Street 27 King Street (Roman road) 33 Military Way (Hadrian's Wall) 36 Peddars Way 37 Portway 39 Pye Road 40 Stane Street (Chichester) 41 Stane Street (Colchester) 46 Stanegate 48 Watling Street 51 Via Devana 56 Wade's Causeway 57 References Article Sources and Contributors 59 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 61 Article Licenses License 63 Roman roads in Britain 1 Roman roads in Britain Roman roads, together with Roman aqueducts and the vast standing Roman army, constituted the three most impressive features of the Roman Empire. In Britain, as in their other provinces, the Romans constructed a comprehensive network of paved trunk roads (i.e. surfaced highways) during their nearly four centuries of occupation (43 - 410 AD). This article focuses on the ca. 2,000 mi (3,200 km) of Roman roads in Britain shown on the Ordnance Survey's Map of Roman Britain.[1] This contains the most accurate and up-to-date layout of certain and probable routes that is readily available to the general public. The pre-Roman Britons used mostly unpaved trackways for their communications, including very ancient ones running along elevated ridges of hills, such as the South Downs Way, now a public long-distance footpath. -

Conservation Area Appraisal & Management Proposals

Usk Conservation Area Appraisal & Management Proposals Document Prepared By: Report Title: Usk Conservation Area Appraisal & Management Proposals Client: Monmouthshire County Council Project Number: 2009/089 Draft Issued: 18 February 2011 2nd Draft Issued: 13 January 2012 3rd Draft Issued: 4 June 2012 4th Draft Issued 25 March 2013 Final Issue 23rd March 2016 © The contents of this document must not be copied or reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of Monmouthshire County Council. All plans are reproduced from the Ordnance Survey Map with the permission of the Controller HMSO, Crown Copyright Reserved, Licence No. 100023415 (Monmouthshire County Council) This document is intended to be printed double-sided. 1 Usk Conservation Area Appraisal & Management Proposals Contents Part A: Purpose & Scope of the Appraisal 5 1 Introduction 5 2 Consultation 5 3 Planning Policy Context 6 4 The Study Area 8 Part B: Conservation Area Appraisal 9 5 Location & Setting 9 6 Historic Development & Archaeology 10 6.1 Historic Background 10 6.2 Settlement Plan 18 6.3 Key Historic Influences & Characteristics 18 6.4 Archaeological Potential 18 7 Spatial Analysis 20 7.1 Background 20 7.2 Overview 20 7.3 Character Areas 22 1. Bridge Street 23 2. New Market Street Environs 29 3. Twyn Square 35 4. Porthycarne Street 38 5. Castle & Castle Parade 43 6. Maryport Street, Church Street & Castle Street 47 7. Prison, Courthouse & Environs 53 8. Mill Street & Environs 55 9. Riverside (including Woodside) 56 7.4 Architectural & Historic Qualities of -

The Chester ‘Command’ System C

The Chester ‘Command’ System c. 71-96 C.E. by Tristan Price A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Classical Studies Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2019 © Tristan Price 2019 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This thesis centres on the operations of the Chester ‘command’ system in the region of North Wales, roughly from the first year in which Petilius Cerialis served as the governor of Britain to the death of Emperor Domitian. Despite the several auxiliary forts that were occupied simultaneously during this period, seven military stations have been selected to demonstrate the direct application of Roman rule in the region imposed by a fortified network of defences and communications: the legionary fortress of Chester, the fortress at Wroxeter, the fort at Forden Gaer, along with Caersws II, Pennal, Caernarfon, and Caerhun. After the fortress at Wroxeter was abandoned c. 90 C.E. the fortress of Chester held sole legionary authority and administered control over the auxiliary units stationed in North Wales and the Welsh midlands. Each fort within this group was strategically positioned to ensure the advantages of its location and environment were exploited. The sites of Wroxeter, Forden Gaer, Caersws II, and Pennal were not only placed on the same road (RR64) to maintain a reliable communications system across the Severn valley, but the paths through which indigenous people could travel north or south were limited as each military post controlled access to the preferred land routes over the River Severn and the River Dyfi. -

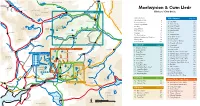

Moelwynion & Cwm Lledr

Llanrwst Llyn Padarn Llyn Ogwen CARNEDDAU Llanberis A5 Llyn Peris B5427 Tryfan Moelwynion & Cwm Lledr A4086 Nant Peris GLYDERAU B5106 Glyder Fach Capel Curig CWM LLEDR MAP PAGE 123 Climbers’ Club Guide Glyder Fawr LLANBERIS PASS A4086 Llynnau Llugwy Mymbyr Introduction A470 Y Moelwynion page 123 The Climbers’ Club 4 Betws-y-Coed Acknowledgments 5 20 Stile Wall 123 B5113 21 Craig Fychan 123 13 Using this guidebook 6 6 Grading 7 22 Craig Wrysgan 123 Carnedd 12 Carnedd Moel-siabod 5 9 10 23 Upper Wrysgan 123 SNOWDON Crag Selector 8 Llyn Llydaw y Cribau 11 3 4 Flora & Fauna 10 24 Moel yr Hydd 123 A470 A5 Rhyd-Ddu Geology 14 25 Pinacl 123 Dolwyddelan Lledr Conwy The Slate Industry 18 26 Waterfall Slab 123 Llyn Gwynant 2 History of Moelwynion Climbing 20 27 Clogwyn yr Oen 123 1 Pentre 8 B4406 28 Carreg Keith 123 Yr Aran -bont Koselig Hour 28 Plas Gwynant Index of Climbs 000 29 Sleep Dancer Buttress 123 7 Penmachno A498 30 Clogwyn y Bustach 123 Cwm Lledr page 30 31 Craig Fach 123 A4085 Bwlch y Gorddinan (Crimea Pass) 1 Clogwyn yr Adar 32 32 Craig Newydd 123 Llyn Dinas MANOD & The TOWN QUARRIES MAP PAGE 123 Machno Ysbyty Ifan 2 Craig y Tonnau 36 33 Craig Stwlan 123 Beddgelert 44 34 Moelwyn Bach Summit Cliffs 123 Moel Penamnen 3 Craig Ddu 38 Y MOELWYNION MAP PAGE 123 35 Moelwyn Bach Summit Quarry 123 Carrog 4 Craig Ystumiau 44 24 29 Cnicht 47 36 Moelwyn Bach Summit Nose 123 Moel Hebog 5 Lone Buttress 48 43 46 B4407 25 30 41 Pen y Bedw Conwy 37 Moelwyn Bach Craig Ysgafn 123 42 Blaenau Ffestiniog 6 Daear Ddu 49 26 31 40 38 38 Craig Llyn Cwm Orthin -

Final Recommendations Report

LOCAL DEMOCRACY AND BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES Review of the Electoral Arrangements of the County of Ceredigion Final Recommendations Report May 2019 © LDBCW copyright 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to the Commission at [email protected] This document is also available from our website at www.ldbc.gov.wales FOREWORD The Commission is pleased to present this Report to the Minister, which contains its recommendations for revised electoral arrangements for the County of Ceredigion. This review is part of the programme of reviews being conducted under the Local Government (Democracy) (Wales) Act 2013, and follows the principles contained in the Commission’s Policy and Practice document. The issue of fairness is at the heart of the Commission’s statutory responsibilities. The Commission’s objective has been to make recommendations that provide for effective and convenient local government, and which respect, as far as possible, local community ties. The recommendations are aimed at improving electoral parity, so that the vote of an individual elector has as equal a value to those of other electors throughout the County, so far as it is possible to achieve. The Commission is grateful to the Members and Officers of Ceredigion County Council for their assistance in its work, to the Community and Town Councils for their valuable contributions, and to all who have made representations throughout the process. -

The Britons in Late Antiquity: Power, Identity And

THE BRITONS IN LATE ANTIQUITY: POWER, IDENTITY AND ETHNICITY EDWIN R. HUSTWIT Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Bangor University 2014 Summary This study focuses on the creation of both British ethnic or ‘national’ identity and Brittonic regional/dynastic identities in the Roman and early medieval periods. It is divided into two interrelated sections which deal with a broad range of textual and archaeological evidence. Its starting point is an examination of Roman views of the inhabitants of the island of Britain and how ethnographic images were created in order to define the population of Britain as 1 barbarians who required the civilising influence of imperial conquest. The discussion here seeks to elucidate, as far as possible, the extent to which the Britons were incorporated into the provincial framework and subsequently ordered and defined themselves as an imperial people. This first section culminates with discussion of Gildas’s De Excidio Britanniae. It seeks to illuminate how Gildas attempted to create a new identity for his contemporaries which, though to a certain extent based on the foundations of Roman-period Britishness, situated his gens uniquely amongst the peoples of late antique Europe as God’s familia. The second section of the thesis examines the creation of regional and dynastic identities and the emergence of kingship amongst the Britons in the late and immediately post-Roman periods. It is largely concerned to show how interaction with the Roman state played a key role in the creation of early kingships in northern and western Britain. The argument stresses that while there were claims of continuity in group identities in the late antique period, the socio-political units which emerged in the fifth and sixth centuries were new entities. -

Dark Sky Reserves Status for Snowdonia Contents

Gwarchodfa Awyr Dywyll Dark Sky Reserve Dark Sky Reserves status for Snowdonia Contents 1. Executive Summary Page 2 2. Introduction to National Parks Page 5 3. Snowdonia National Park Page 6 4. The Problem of Light Pollution Page 11 5. Countering Light Pollution Page 12 6. Letters of Support Page 18 7. The Snowdonia Seeing Stars Initiative’s Anti Light Pollution Strategy Page 19 8. The Proposed IDSR Page 20 9. The Night Sky Quality Survey Page 24 10. The External Lighting Audit Page 28 11. Lighting Management Page 30 12. Communication and Collaboration Page 32 12.1. Media Coverage and Publicity 12.2. Education and Events 12.3. Local Government 13. Lighting Improvements Page 38 14. The Future Page 41 Dark Sky Reserves Snowdonia for status Gwarchodfa Awyr Dywyll Dark Sky Reserve 1.0 Executive Summary This document sets out Snowdonia National Park Authority’s application to the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA) to designate Snowdonia National Park (SNP) as an International Dark Sky Reserve (IDSR). Snowdonia National Park Authority (SNPA) is committed to the protection and conservation of all aspects of the environment, including the night sky, and as such supports the mission and goals of the IDA. The Authority believes that achieving IDSR status for the SNP will further raise the profile of the Light Pollution issue in Wales following the successful application from the Brecon Beacons National Park Authority in 2013. It will assist SNPA in gaining support in protecting the excellent quality of dark skies which we already have in Snowdonia from the general public, business, and politicians, and to improve it further where needed. -

Whitchurch Market Town Profile

Whitchurch Market Town Profile Autumn 2017 1 INFORMATION, INTELLI GENCE & INSIGHT TEAM Contents Section Page Introduction 3 Local Politics 5 Demographics 7 Economy 13 Tourism & Leisure 29 Health 32 Housing 36 Education 41 Transport & Infrastructure 42 Community Safety 43 Additional Information 45 2 INFORMATION, INTELLI GENCE & INSIGHT TEAM Phone: 0345 678 9000 Email: [email protected] Market Town Profile Whitchurch Whitchurch is the northern most market town in Shropshire located on the border of Cheshire and Wales. The town has been inhabited since Roman times and is still a thriving market town. This North Shropshire market town has many buildings dating from Medieval ,Tudor and Georgian times. Whitchurch is amongst the oldest continually inhabited towns in the county. Within the town is the wooded Victoria Jubilee Park and picturesque Memorial Garden. Named Mediolanum by the Romans and chosen for its strategic location, Whitchurch soon had legions passing through to reach the outposts of Roman Britain. The town was the heart of the Roman road network, a fact reflected today, and one that makes Whitchurch so central and accessible for visitors. The Whitchurch firm of J B Joyce (tower clock makers) was established in 1690. Whitchurch Heritage Centre hosts information on J B Joyce for visitors. These clocks have an international reputation and can be found on cathedrals and palaces from Singapore to Kabul. Many examples of Joyce’s work can be seen around the town making Whitchurch “the Home of Tower Clocks”. The town is surrounded by beautiful countryside and there are walks along the North Shropshire Canals to Grindley Brook and through the Whitchurch Waterways County Park, also a haven for wildlife and containing Greenfields Nature Reserve managed by The Wildlife Trust. -

Roman Roads in Britain

ROMAN ROADS IN BRITAIN c < t < r c ROMAN ROADS IN BRITAIN BY THE LATE THOMAS CODRINGTON M, INST.C. E., F. G S. fFITH LARGE CHART OF THE ROMAN ROADS AND SMALL MAPS IN THE TEXT REPRINT OF THIRD EDITION LONDON SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1919 . • r r 11 'X/^i-r * ' Ci First Edition^ 1903 Second Edition, Revised, 1905 Tliird Edition, Revised, 1918 (.Reprint), 19 „ ,, 19 PREFACE The following attempt to describe the Roman roads of Britain originated in observations made in all parts of the country as opportunities presented themselves to me from time to time. On turning to other sources of information, the curious fact appeared that for a century past the litera- ture of the subject has been widely influenced by the spurious Itinerary attributed to Richard of Cirencester. Though that was long ago shown to be a forgery, statements derived from it, and suppositions founded upon them, are continually repeated, casting suspicion sometimes unde- served on accounts which prove to be otherwise accurate. A wide publicity, and some semblance of authority, have been given to imaginary roads and stations by the new Ordnance maps. Those who early in the last century, under the influence of the new Itinerary, traced the Roman roads, unfortunately left but scanty accounts of the remains which came under their notice, many of which have since been destroyed or covered up in the making of modern roads; and with the evidence now available few Roman roads can be traced continuously. The gaps can often be filled with reasonable certainty, but more often the precise course is doubtful, and the entire course of some roads connecting known stations of the Itinerary of Antonine can only be guessed at.