Albert J. Beveridge and Demythologizing Lincoln JOHN BRAEMAN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music and the American Civil War

“LIBERTY’S GREAT AUXILIARY”: MUSIC AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR by CHRISTIAN MCWHIRTER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Christian McWhirter 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Music was almost omnipresent during the American Civil War. Soldiers, civilians, and slaves listened to and performed popular songs almost constantly. The heightened political and emotional climate of the war created a need for Americans to express themselves in a variety of ways, and music was one of the best. It did not require a high level of literacy and it could be performed in groups to ensure that the ideas embedded in each song immediately reached a large audience. Previous studies of Civil War music have focused on the music itself. Historians and musicologists have examined the types of songs published during the war and considered how they reflected the popular mood of northerners and southerners. This study utilizes the letters, diaries, memoirs, and newspapers of the 1860s to delve deeper and determine what roles music played in Civil War America. This study begins by examining the explosion of professional and amateur music that accompanied the onset of the Civil War. Of the songs produced by this explosion, the most popular and resonant were those that addressed the political causes of the war and were adopted as the rallying cries of northerners and southerners. All classes of Americans used songs in a variety of ways, and this study specifically examines the role of music on the home-front, in the armies, and among African Americans. -

The Cosmos Club: a Self-Guided Tour of the Mansion

Founded 1878 The Cosmos Club - A Self-Guided Tour of the Mansion – 2121 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20008 Founders’ Objectives: “The advancement of its members in science, literature, and art,” and also “their mutual improvement by social intercourse.” he Cosmos Club was founded in 1878 in the home of John Wesley Powell, soldier and explorer, ethnologist and T Director of the Geological Survey. Powell’s vision was that the Club would be a center of good fellowship, one that embraced the sciences and the arts, where members could meet socially and exchange ideas, where vitality would grow from the mixture of disciplines, and a library would provide a refuge for thought and learning. www.cosmosclub.org Welcome to The Townsend Mansion This brochure is designed to guide you on a walking tour of the public rooms of the Clubhouse. Whether member or guest, please enjoy the beauty surrounding you and our hospitality. You stand within an historic mansion, replete with fine and decorative arts belonging to the Cosmos Club. The Townsend Mansion is the fifth home of the Cosmos Club. Within the Clubhouse, Presidents, members of Congress, ambassadors, Nobel Laureates, Pulitzer Prize winners, scientists, writers, and other distinguished individuals have expanded their minds, solved world problems, and discovered new ways to make contributions to humankind, just as the founders envisioned in 1878. The history of the Cosmos Club is present in every room, not as homage to the past, but as a celebration of its continuum serving as a reminder of its origins, its genius, and its distinction. ❖❖❖ A place for conscious, animated discussion A place for quiet, contemplation and research A place to free the mind through relaxation, music, art, and conviviality Or exercise the mind and match wits A place of discovery A haven of friendship… The Cosmos Club A Brief History The Townsend Mansion, home of the Cosmos Club since 1952, was originally built in 1873 by Judge Curtis J. -

Abraham Lincoln and the Power of Public Opinion Allen C

Civil War Era Studies Faculty Publications Civil War Era Studies 2014 "Public Sentiment Is Everything": Abraham Lincoln and the Power of Public Opinion Allen C. Guelzo Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cwfac Part of the Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Guelzo, Allen C. "'Public Sentiment Is Everything': Abraham Lincoln and the Power of Public Opinion." Lincoln and Liberty: Wisdom for the Ages Ed. Lucas E. Morel (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2014), 171-190. This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cwfac/56 This open access book chapter is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Public Sentiment Is Everything": Abraham Lincoln and the Power of Public Opinion Abstract Book Summary: Since Abraham Lincoln’s death, generations of Americans have studied his life, presidency, and leadership, often remaking him into a figure suited to the needs and interests of their own time. This illuminating volume takes a different approach to his political thought and practice. Here, a distinguished group of contributors argue that Lincoln’s relevance today is best expressed by rendering an accurate portrait of him in his own era. They es ek to understand Lincoln as he understood himself and as he attempted to make his ideas clear to his contemporaries. -

William Allen White Newspaper Editor ( 1868 - 1944 )

William Allen White Newspaper editor ( 1868 - 1944 ) William Allen White was a renowned newspaper editor, politician, and author. Between the two world wars, White, known as the “Sage of Emporia,” became the iconic middle-American spokesman for millions throughout the United States. Born in Emporia, Kansas, White attended the College of Emporia and the University of Kansas. In 1892 he started work at The Kansas City Star as an editorial writer and a year later married Sallie Lindsay. In 1895, White purchased his hometown newspaper, the Emporia Gazette for $3,000. He burst on to the national scene with an August 16, 1896 editorial entitled “What’s the Matter With Kansas?” White developed a friendship with President THEODORE ROOSEVELT in the1890s that lasted until Roosevelt’s death in 1919. The two would be instrumental in forming the Progressive (Bull-Moose) Party in 1912 in opposition to the forces surrounding incumbent Republican president WILLIAM HOWARD TAFT. Later, White supported much of the New Deal, but opposed FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT in his first three Presidential elec- tions. White died before voting in the 1944 election. Courtesy of Kenneth Neill Despite differences with FDR, White agreed to Roosevelt’s request to help generate public support for the Allies before America’s entrance into World War II. White was fundamental in the formation of the Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies, sometimes known asthe White Committee. He spent much of his last three years involved with the committee. He won a 1923 Pulitzer Prize for an editorial he wrote after being arrest- ed in a dispute over free speech following objections to the way Kan- sas treated the workers who participated in the railroad strike of 1922. -

Will Rogers and Calvin Coolidge

Summer 1972 VoL. 40 No. 3 The GfJROCEEDINGS of the VERMONT HISTORICAL SOCIETY Beyond Humor: Will Rogers And Calvin Coolidge By H. L. MEREDITH N August, 1923, after Warren G. Harding's death, Calvin Coolidge I became President of the United States. For the next six years Coo lidge headed a nation which enjoyed amazing economic growth and relative peace. His administration progressed in the midst of a decade when material prosperity contributed heavily in changing the nature of the country. Coolidge's presidency was transitional in other respects, resting a bit uncomfortably between the passions of the World War I period and the Great Depression of the I 930's. It seems clear that Coolidge acted as a central figure in much of this transition, but the degree to which he was a causal agent, a catalyst, or simply the victim of forces of change remains a question that has prompted a wide range of historical opinion. Few prominent figures in United States history remain as difficult to understand as Calvin Coolidge. An agrarian bias prevails in :nuch of the historical writing on Coolidge. Unable to see much virtue or integrity in the Republican administrations of the twenties, many historians and friends of the farmers followed interpretations made by William Allen White. These picture Coolidge as essentially an unimaginative enemy of the farmer and a fumbling sphinx. They stem largely from White's two biographical studies; Calvin Coolidge, The Man Who Is President and A Puritan in Babylon, The Story of Calvin Coolidge. 1 Most notably, two historians with the same Midwestern background as White, Gilbert C. -

American Historical Association

ANNUAL REPORT Of THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION fOR THE YEAR 1914 IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. I :'\ !j' J !\T .1'__ ,,:::;0 '" WASHINGTON 1916 LETTER OF SUBMITTAL. SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, Washington, D.O., February 135, 1916. To the Oongress of the United States: In accordance with the act of incorporation of the American Historical Association, approved January 4, 1889, I have the honor to submit to Congress the annual report of the association for the year 1914. I have the honor to be, Very respectfully, your obedient servant, CHAru.Es D. WALCOTI', Searetary. 3 ACT OF INCORPORATION. Be it enacted by the Senate UJTUi House of Representatives of the United States of America in Oongress assembled, That Andrew D. White, of Ithaca, in the State of New York; George Bancroft, of Washington, in the District of Columbia; Justin Winsor, of Cam bridge, in the State of Massachusetts; William F. Poole, of Chicago, in the State of Dlinois; Herbert B. Adams, of Baltimore, in the State of Maryland; Clarence W. Bowen, of Brooklyn, in the State of New York, their associates and successors, are hereby created, in the Dis trict of Columbia, a body corporate and politic by the name of the American Historical Association, for the promotion of historical studies, the collection and preservation of historical manuscripts, and for kindred purposes in the interest of American history and of history in America. Said association is authorized to hold real and personal estate. in the District of Columbia so far only as may be nesessary to its lawful ends to an amount not exceeding five hundred thousand dollars, to adopt a constitution, and make by-laws not inconsistent with law. -

The American West: from Frontier to Region

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 64 Number 2 Article 2 4-1-1989 The American West: From Frontier to Region Martin Ridge Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Ridge, Martin. "The American West: From Frontier to Region." New Mexico Historical Review 64, 2 (1989). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol64/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American West: From Frontier to Region MARTIN RIDGE We are fast approaching the centennial of the Bureau of the Census' 1890 declaration of the closing of the frontier. It would seem appro priate to mark that centennial by asking why and how American his torians became interested in the history of the American frontier, and why and how, in recent years, there has been increasing attention paid to the West as a region. And why studying the West as a region poses special problems. The history of the frontier and the regional West are not the same, but there is a significant intellectual overlay that warrants examination. A little more than a century ago the scholarly discipline of Amer ican history was in its formative stages. The tradition of gifted au thors-men like Francis Parkman, Brooks Adams, Theodore Roosevelt, Martin Ridge, Senior Research Associate and Director of Research at the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, and professor of history at the California Institute of Technology, served as editor of the Journal of American History for eleven years. -

Xerox University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

~Tntritau~I~Tgtital Ituitur

VolumeXXIv] [Number 3 ~tntritau~i~tgtital Ituitur THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION, I9I9 EMBERS of the American Historical Association expect to M find at the beginning of the April number of this journal an account of the transactions of the annual meeting of the Associa tion, customarily held in the last days of December preceding, and with it certain items of formal matter relating to the meeting, such as the text of important votes passed by the Association or the Executive Council, a summary of the treasur~r's report, an exhibit of the budget or estimated receipts and expenditures or appropria tions, and a list of the officers of the Association and of the various committees appointed by the Executive Council. The thirty-fourth annual meeting, which was to have taken place at Cleveland on December 27 and 28, was indefinitely postponed on' account of a strong recommendation, received from the health officer of that city a few days before the date on which the meeting should have taken place, that it should be omitted because of the epidemic of influenza then prevailing in Cleveland. Yet, though there is no annual meeting to chronicle in these pages, it will be convenient to members that the formal matter spoken of above should be found in its customary place. Moreover, though no meeting of the Asso ciation has taken place, there was a meeting of the Executive Council held in New York on January 31 and February I, 1919, some of the transactions of which, analogous to those of the Asso ciation in its annual business meeting, may here for convenience be described. -

American Exceptionalism Or Atlantic Unity? Fredrick Jackson Turner and the Enduring Problem of American Historiography

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 89 Number 3 Article 4 7-1-2014 American Exceptionalism or Atlantic Unity? Fredrick Jackson Turner and the Enduring Problem of American Historiography Kevin Jon Fernlund Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Fernlund, Kevin Jon. "American Exceptionalism or Atlantic Unity? Fredrick Jackson Turner and the Enduring Problem of American Historiography." New Mexico Historical Review 89, 3 (2014). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol89/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. American Exceptionalism or Atlantic Unity? Frederick Jackson Turner and the Enduring Problem of American Historiography • KEVIN JON FERNLUND The Problem: Europe and the History of America n 1892 the United States celebrated the four hundredth anniversary of Chris- topher Columbus’s discovery of lands west of Europe, on the far side of the IAtlantic Ocean. To mark this historic occasion, and to showcase the nation’s tremendous industrial progress, the city of Chicago hosted the World’s Colum- bian Exposition. Chicago won the honor after competing with other major U.S. cities, including New York. Owing to delays, the opening of the exposition was pushed back to 1893. This grand event was ideally timed to provide the coun- try’s nascent historical profession with the opportunity to demonstrate its value to the world. The American Historical Association (AHA) was founded only a few years prior in 1884, and incorporated by the U.S. -

AHA Colloquium

Cover.indd 1 13/10/20 12:51 AM Thank you to our generous sponsors: Platinum Gold Bronze Cover2.indd 1 19/10/20 9:42 PM 2021 Annual Meeting Program Program Editorial Staff Debbie Ann Doyle, Editor and Meetings Manager With assistance from Victor Medina Del Toro, Liz Townsend, and Laura Ansley Program Book 2021_FM.indd 1 26/10/20 8:59 PM 400 A Street SE Washington, DC 20003-3889 202-544-2422 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.historians.org Perspectives: historians.org/perspectives Facebook: facebook.com/AHAhistorians Twitter: @AHAHistorians 2020 Elected Officers President: Mary Lindemann, University of Miami Past President: John R. McNeill, Georgetown University President-elect: Jacqueline Jones, University of Texas at Austin Vice President, Professional Division: Rita Chin, University of Michigan (2023) Vice President, Research Division: Sophia Rosenfeld, University of Pennsylvania (2021) Vice President, Teaching Division: Laura McEnaney, Whittier College (2022) 2020 Elected Councilors Research Division: Melissa Bokovoy, University of New Mexico (2021) Christopher R. Boyer, Northern Arizona University (2022) Sara Georgini, Massachusetts Historical Society (2023) Teaching Division: Craig Perrier, Fairfax County Public Schools Mary Lindemann (2021) Professor of History Alexandra Hui, Mississippi State University (2022) University of Miami Shannon Bontrager, Georgia Highlands College (2023) President of the American Historical Association Professional Division: Mary Elliott, Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (2021) Nerina Rustomji, St. John’s University (2022) Reginald K. Ellis, Florida A&M University (2023) At Large: Sarah Mellors, Missouri State University (2021) 2020 Appointed Officers Executive Director: James Grossman AHR Editor: Alex Lichtenstein, Indiana University, Bloomington Treasurer: William F. -

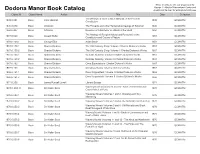

Catalog Records April 7, 2021 6:03 PM Object Id Object Name Author Title Date Collection

Catalog Records April 7, 2021 6:03 PM Object Id Object Name Author Title Date Collection 1839.6.681 Book John Marshall The Writings of Chief Justice Marshall on the Federal 1839 GCM-KTM Constitution 1845.6.878 Book Unknown The Proverbs and other Remarkable Sayings of Solomon 1845 GCM-KTM 1850.6.407 Book Ik Marvel Reveries of A Bachelor or a Book of the Heart 1850 GCM-KTM The Analogy of Religion Natural and Revealed, to the 1857.6.920 Book Joseph Butler 1857 GCM-KTM Constitution and Course of Nature 1859.6.1083 Book George Eliot Adam Bede 1859 GCM-KTM 1867.6.159.1 Book Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.159.2 Book Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.160.1 Book Charles Dickens Nicholas Nickleby: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.160.2 Book Charles Dickens Nicholas Nickleby: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.162 Book Charles Dickens Great Expectations: Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.163 Book Charles Dickens Christmas Books: Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1868.6.161.1 Book Charles Dickens David Copperfield: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1868 GCM-KTM 1868.6.161.2 Book Charles Dickens David Copperfield: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1868 GCM-KTM 1871.6.359 Book James Russell Lowell Literary Essays 1871 GCM-KTM 1876.6.