Nybster, Caithness Conservation Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 1: Gazetteer of Sites

Woven Into the Stuff of Other Men's Lives: The Treatment of the Dead in Iron Age Atlantic Scotland. Item Type Thesis Authors Tucker, Fiona C. Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 30/09/2021 23:37:07 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/5327 389 Appendix 1: Gazetteer of Sites This gazetteer of sites includes all sites included in the study. A brief description of each site, with NMRS number and national grid code, date of excavation and references, along with a description of the human remains found and the reason for considering these to be Iron Age is provided. The sites are presented according to the numbered system used throughout this study, starting in the north from Shetland and working south to Argyll, and in alphabetical order within each region. Those sites with locatable human remains that were examined by the author are marked with a star, and can be cross-referenced with Appendix 2, where the osteological data is presented site by site. Sites from which human remains were radiocarbon dated can also be cross referenced with Appendix 3, radiocarbon dates. 390 Shetland (sites 1-7) 1. Jarlshof NMRS number: HU30NE 1.0 National grid reference: HU 3981 0955 Excavated: Curle 1925-35, Childe 1937, Hamilton 1949-52 Principle references: Curle 1933, Hamilton 1956 Brief description: Multi-period settlement including Bronze Age, Early Iron Age, Middle Iron Age, Late Iron Age, Norse and Medieval structures Human remains: One parietal fragment recovered from the passageway of an Early Iron Age structure, and one cranial fragment from medieval layers Dating evidence: Radiocarbon dating of bone (see Appendix 3) Location of human remains: National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh* 2. -

Caithness County Council

Caithness County Council RECORDS’ IDENTITY STATEMENT Reference number: CC Alternative reference number: Title: Caithness County Council Dates of creation: 1720-1975 Level of description: Fonds Extent: 10 bays of shelving Format: Mainly paper RECORDS’ CONTEXT Name of creators: Caithness County Council Administrative history: 1889-1930 County Councils were established under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889. They assumed the powers of the Commissioners of Supply, and of Parochial Boards, excluding those in Burghs, under the Public Health Acts. The County Councils also assumed the powers of the County Road Trusts, and as a consequence were obliged to appoint County Road Boards. Powers of the former Police Committees of the Commissioners were transferred to Standing Joint Committees, composed of County Councillors, Commissioners and the Sheriff of the county. They acted as the police committee of the counties - the executive bodies for the administration of police. The Act thus entrusted to the new County Councils most existing local government functions outwith the burghs except the poor law, education, mental health and licensing. Each county was divided into districts administered by a District Committee of County Councillors. Funded directly by the County Councils, the District Committees were responsible for roads, housing, water supply and public health. Nucleus: The Nuclear and Caithness Archive 1 Provision was also made for the creation of Special Districts to be responsible for the provision of services including water supply, drainage, lighting and scavenging. 1930-1975 The Local Government Act (Scotland) 1929 abolished the District Committees and Parish Councils and transferred their powers and duties to the County Councils and District Councils (see CC/6). -

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide 2 Introduction Scotland is surrounded by coastal water – the North Sea, the Irish Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. In addition, there are also numerous bodies of inland water including rivers, burns and about 25,000 lochs. Being safe around water should therefore be a key priority. However, the management of water safety is a major concern for Scotland. Recent research has found a mixed picture of water safety in Scotland with little uniformity or consistency across the country.1 In response to this research, it was suggested that a framework for a water safety policy be made available to local authorities. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) has therefore created this document to assist in the management of water safety. In order to support this document, RoSPA consulted with a number of UK local authorities and organisations to discuss policy and water safety management. Each council was asked questions around their own area’s priorities, objectives and policies. Any policy specific to water safety was then examined and analysed in order to help create a framework based on current practice. It is anticipated that this framework can be localised to each local authority in Scotland which will help provide a strategic and consistent national approach which takes account of geographical areas and issues. Water Safety Policy in Scotland— A Guide 3 Section A: The Problem Table 1: Overall Fatalities 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 Data from National Water Safety Forum, WAID database, July 14 In recent years the number of drownings in Scotland has remained generally constant. -

Modern Rune Carving in Northern Scotland. Futhark 8

Modern Rune Carving in Northern Scotland Andrea Freund and Ragnhild Ljosland (University of the Highlands and Islands) Abstract This article discusses modern runic inscriptions from Orkney and Caithness. It presents various examples, some of which were previously considered “genuine”, and reveals that OR 13 Skara Brae is of modern provenance. Other examples from the region can be found both on boulders or in bedrock and in particular on ancient monuments ranging in date from the Neolithic to the Iron Age. The terminology applied to modern rune carving, in particular the term “forgery”, is examined, and the phenomenon is considered in relation to the Ken sington runestone. Comparisons with modern rune carving in Sweden are made and suggestions are presented as to why there is such an abundance of recently carved inscriptions in Northern Scotland. Keywords: Scotland, Orkney, Caithness, modern runic inscriptions, modern rune carving, OR 13 Skara Brae, Kensington runestone Introduction his article concerns runic inscriptions from Orkney and Caithness Tthat were, either demonstrably or arguably, made in the modern period. The objective is twofold: firstly, the authors aim to present an inventory of modern inscriptions currently known to exist in Orkney and Caith ness. Secondly, they intend to discuss the concept of runic “forgery”. The question is when terms such as “fake” or “forgery” are helpful in de scribing a modern runic inscription, and when they are not. Included in the inventory are only those inscriptions which may, at least to an untrained eye, be mistaken for premodern. Runes occurring for example on jewellery, souvenirs, articles of clothing, in logos and the Freund, Andrea, and Ragnhild Ljosland. -

Further Studies of a Staggered Hybrid Zone in Musmusculus Domesticus (The House Mouse)

Heredity 71 (1993) 523—531 Received 26 March 1993 Genetical Society of Great Britain Further studies of a staggered hybrid zone in Musmusculus domesticus (the house mouse) JEREMYB. SEARLE, YOLANDA NARAIN NAVARRO* & GUILA GANEMI Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS,U.K. Inthe extreme north-east of Scotland (near the village of Joim o'Groats) there is a small karyotypic race of house mouse (2n= 32), characterized by four metacentric chromosomes 4.10, 9.12, 6.13 and 11.14. We present new data on the hybrid zone between this form and the standard race (2n =40)and show an association between race and habitat. In a transect south of John o'Groats we demonstrate that the dines for arm combinations 4.10 and 9.12 are staggered relative to the dines for 6.13 and 11.14, confirming previous data collected along an east—west transect (Searle, 1991). There are populations within the John o'Groats—standard hybrid zone dominated by individuals with 36 chromosomes (homozygous for 4.10 and 9.12), which may represent a novel karyotypic form that has arisen within the zone. Alternatively the type with 36 chromosomes may have been the progenitor of the John o'Groats race. Additional cytogenetic interest is provided by the occur- rence of a homogeneous staining region on one or both copies of chromosome 1 in some mice from the zone. Keywords:chromosomalvariation, hybrid zones, Mus musculus domesticus, Robertsonian fusions, staggered dines. Introduction (Rb) fusion of two ancestral acrocentrics with, for Thestandard karyotype of the house mouse consists of instance, metacentric 4.10 derived by fusion of acro- 40 acrocentric chromosomes. -

Allasdale Dunes, Barra, Western Isles, Scotland

Wessex Archaeology Allasdale Dunes, Barra Western Isles, Scotland Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Ref: 65305 October 2008 Allasdale Dunes, Barra, Western Isles, Scotland Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Prepared on behalf of: Videotext Communications Ltd 49 Goldhawk Road LONDON W12 8QP By: Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB Report reference: 65305.01 October 2008 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2008, all rights reserved Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 Allasdale Dunes, Barra, Western Isles, Scotland Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Contents Summary Acknowledgements 1 BACKGROUND..................................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction................................................................................................1 1.2 Site Location, Topography and Geology and Ownership ......................1 1.3 Archaeological Background......................................................................2 Neolithic.......................................................................................................2 Bronze Age ...................................................................................................2 Iron Age........................................................................................................4 1.4 Previous Archaeological Work at Allasdale ............................................5 2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES.................................................................................6 -

Land, Stone, Trees, Identity, Ambition

Edinburgh Research Explorer Land, stone, trees, identity, ambition Citation for published version: Romankiewicz, T 2015, 'Land, stone, trees, identity, ambition: The building blocks of brochs', The Archaeological Journal, vol. 173 , no. 1, pp. 1-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/00665983.2016.1110771 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1080/00665983.2016.1110771 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: The Archaeological Journal General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Land, Stone, Trees, Identity, Ambition: the Building Blocks of Brochs Tanja Romankiewicz Brochs are impressive stone roundhouses unique to Iron Age Scotland. This paper introduces a new perspective developed from architectural analysis and drawing on new survey, fieldwork and analogies from anthropology and social history. Study of architectural design and constructional detail exposes fewer competitive elements than previously anticipated. Instead, attempts to emulate, share and communicate identities can be detected. The architectural language of the broch allows complex layers of individual preferences, local and regional traditions, and supra-regional communications to be expressed in a single house design. -

Housing Application Guide Highland Housing Register

Housing Application Guide Highland Housing Register This guide is to help you fill in your application form for Highland Housing Register. It also gives you some information about social rented housing in Highland, as well as where to find out more information if you need it. This form is available in other formats such as audio tape, CD, Braille, and in large print. It can also be made available in other languages. Contents PAGE 1. About Highland Housing Register .........................................................................................................................................1 2. About Highland House Exchange ..........................................................................................................................................2 3. Contacting the Housing Option Team .................................................................................................................................2 4. About other social, affordable and supported housing providers in Highland .......................................................2 5. Important Information about Welfare Reform and your housing application ..............................................3 6. Proof - what and why • Proof of identity ...............................................................................................................................4 • Pregnancy ...........................................................................................................................................5 • Residential access to children -

Iron Age Scotland: Scarf Panel Report

Iron Age Scotland: ScARF Panel Report Images ©as noted in the text ScARF Summary Iron Age Panel Document September 2012 Iron Age Scotland: ScARF Panel Report Summary Iron Age Panel Report Fraser Hunter & Martin Carruthers (editors) With panel member contributions from Derek Alexander, Dave Cowley, Julia Cussans, Mairi Davies, Andrew Dunwell, Martin Goldberg, Strat Halliday, and Tessa Poller For contributions, images, feedback, critical comment and participation at workshops: Ian Armit, Julie Bond, David Breeze, Lindsey Büster, Ewan Campbell, Graeme Cavers, Anne Clarke, David Clarke, Murray Cook, Gemma Cruickshanks, John Cruse, Steve Dockrill, Jane Downes, Noel Fojut, Simon Gilmour, Dawn Gooney, Mark Hall, Dennis Harding, John Lawson, Stephanie Leith, Euan MacKie, Rod McCullagh, Dawn McLaren, Ann MacSween, Roger Mercer, Paul Murtagh, Brendan O’Connor, Rachel Pope, Rachel Reader, Tanja Romankiewicz, Daniel Sahlen, Niall Sharples, Gary Stratton, Richard Tipping, and Val Turner ii Iron Age Scotland: ScARF Panel Report Executive Summary Why research Iron Age Scotland? The Scottish Iron Age provides rich data of international quality to link into broader, European-wide research questions, such as that from wetlands and the well-preserved and deeply-stratified settlement sites of the Atlantic zone, from crannog sites and from burnt-down buildings. The nature of domestic architecture, the movement of people and resources, the spread of ideas and the impact of Rome are examples of topics that can be explored using Scottish evidence. The period is therefore important for understanding later prehistoric society, both in Scotland and across Europe. There is a long tradition of research on which to build, stretching back to antiquarian work, which represents a considerable archival resource. -

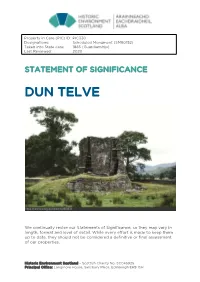

Dun Telve Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC330 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90152) Taken into State care: 1885 (Guardianship) Last Reviewed: 2020 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE DUN TELVE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2020 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND -

P898: the Barrett Family Collection

P898: The Barrett Family Collection RECORDS’ IDENTITY STATEMENT Reference number: P898 Alternative reference number: Title: The Barret Family Collection Dates of creation: 1898 - 2015 Level of description: Fonds Extent: 7 linear meters Format: Paper, Wood, Glass, fabrics, alloys RECORDS’ CONTEXT Name of creators: Administrative history: Custodial history: Deposited by Margret Shearer RECORDS’ CONTENT Description: Appraisal: Accruals: RECORDS’ CONDITION OF ACC. ESS AND USE Access: Open Closed until: - Access conditions: Available within the Archive searchroom Copying: Copying permitted within standard Copyright Act parameters Finding aids: Available in Archive searchroom ALLIED MATERIALS Related material: Publication: Notes: Nucleus: The Nuclear and Caithness Archive 1 Date of catalogue: 02 Feb 2018 Ref. Description Dates P898/1 Diaries 1975-2004 P898/1/1 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1975 P898/1/2 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1984 P898/1/3 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1987 P898/1/4 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1988 P898/1/5 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1989 P898/1/6 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1990 P898/1/7 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1991 P898/1/8 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1992 P898/1/9 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1993 P898/1/10 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1995 P898/1/11 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1996 P898/1/12 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1997 P898/1/13 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1998 P898/1/14 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1999 P898/1/15 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 2000 P898/1/16 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 2001 P898/1/17 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 2002 P898/1/18/1 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 2003 P898/1/18/2 Envelope containing a newspaper clipping, receipts, 2003 addresses and a ticket to the Retired Police Officers Association, Scotland Highlands and Island Branch 100 Club (Inside P898/1/18/1). -

77 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

77 bus time schedule & line map 77 Gills View In Website Mode The 77 bus line (Gills) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Gills: 8:32 AM - 5:35 PM (2) John O' Groats: 1:05 PM (3) Wick: 9:12 AM - 6:15 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 77 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 77 bus arriving. Direction: Gills 77 bus Time Schedule 38 stops Gills Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 8:32 AM - 5:35 PM Town Hall, Wick Bridge Street, Wick Tuesday 8:32 AM - 5:35 PM Post O∆ce, Wick Wednesday 8:32 AM - 5:35 PM Oag Lane, Wick Thursday 8:32 AM - 5:35 PM Elm Tree Garage, Wick Friday 8:32 AM - 5:35 PM George Street, Wick Saturday 8:32 AM - 5:35 PM Hill Avenue, Wick North Road, Scotland Tesco, Wick 77 bus Info Tesco, Wick Direction: Gills Stops: 38 Business Park, Wick Trip Duration: 39 min Line Summary: Town Hall, Wick, Post O∆ce, Wick, Road End, Ackergill Elm Tree Garage, Wick, Hill Avenue, Wick, Tesco, Wick, Tesco, Wick, Business Park, Wick, Road End, Ackergill, Sands Road End, Reiss Sands Road End, Reiss, Crossroads, Reiss, Lower Reiss Road End, Reiss, Quoys Of Reiss, Reiss, Crossroads, Reiss Killimster Road End, Keiss, Lyth Road End, Keiss, Beach Road End, Keiss, Old Garage, Keiss, Hawkhill Lower Reiss Road End, Reiss Road End, Keiss, Road End, Nybster, Petrol Station, Auckengill, Park View Road End, Auckengill, Freswick Quoys Of Reiss, Reiss House Road End, Freswick, Skirza Road End, Freswick, Tofts House, Freswick, Canisbay Road End, Freswick, Hilltop House, John O'