Toward a Social History of Beadmakers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

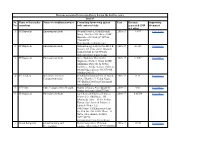

Revenue Generated from Consultancy During the Last Five Years 2015-16 Sr. No. Name of the Teacher Consultant Name of Consultancy

Revenue generated from consultancy during the last five years 2015-16 Sr. Name of the teacher Name of consultancy project Consulting/Sponsoring agency Revenue Supporting No. consultant with contact details generated (INR document in Lakhs) 1 V J Lakhera Evaluate Thermal conductivity, Multiproducts, 202-204, GIDC 0.3 Click Here density, closed cell, Nandesari, Dist Vadodara, India Ph compressive strength and fire +91-265-23062091 properties and witness request multiproducts@yahoocom for the interpretation of the properties of their Thermal insulating materials at various temperature and suitability of industrial application of the materials 2 V J Lakhera Determination of density, Multiproducts, 202-204, GIDC 0.1045 Click Here closed cell content and Nandesari, Dist Vadodara, India Ph compressive strength +91-265-23062091 multiproducts@yahoocom 3 V J Lakhera Determine Thermal Keltech Energies Ltd, 0.15 Click Here Conductivity Value (IHI) PO Vishwasnagar, Karkala Taluk, Muniyal, Udupi Dist, Bangaluru, Karnataka 574108 jatin@perlitein M: 9016255349 4 V J Lakhera Determine Thermal Keltech Energies Ltd, 0.3 Click Here conductivity Value (Samsung) PO Vishwasnagar, Karkala Taluk, Muniyal, Udupi Dist, Bangaluru Karnataka 574108 jatin@perlitein M: 9016255349 5 V J Lakhera Determination of Thermal Dynaweld Engineering Company 0.37 Click Here conductivity, Density, Chloride Private Limited, 72/427 Vijaynagar, content, Sulpher Content, Naranpura Vistar, Ahmedabad - Moisture Absorption 380013 079-27436896 6 V J Lakhera Determination of Compressive -

Ar. Siddharth S. Jadon, International Journal of Research in Engineering, IT and Social Sciences, ISSN 2250-0588, Impact Factor

Ar. Siddharth S. Jadon, International Journal of Research in Engineering, IT and Social Sciences, ISSN 2250-0588, Impact Factor: 6.565, Volume 09 Issue 03, March 2019, Page 89-91 Analysing Tourist Carrying Capacity of Lakhera Gali for promoting Tourism: Old Gwalior Ar. Siddharth S. Jadon (Asso.Professor, Amity University, Maharajpura Dang, Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India) Abstract: India is a country known for its cultural, religious, spiritual and historic value. The heritage categories divided into two categories i.e tangible and intangible. The built heritage sites which are spreading all over the country are of both natures. To develop such sites ministry of tourism are focusing to promote the new tourism sites which have the potential to showcase the living tradition. So the feasibility will be check for carrying capacity of the tourist and proposed the tourist amenities on such sites. The sites which are promoted for tourist places should be checked for the carrying capacity, so the locals and structure should not be harmed and a cap can be suggested over such sites. In this study, a case of Gwalior street is taken for a pilot study. Keywords: Carrying Capacity, Gwalior, Lakhera Gali, Heritage I. INTRODUCTION Gwalior, a major urban settlement of the state of Madhya Pradesh. It is a prominent historical city, which lies in Madhya Pradesh state. The City of old Gwalior covers an area of 2.5 sq.km. The Gwalior fort is situated in the centre of the city. The city today encompasses three distinct old settlements of Old Gwalior (6th century onwards), Lashkar (18th century onwards) and Morar (19th century onwards) with its origin traced to the 5th century. -

Women-Empowerment a Bibliography

Women’s Studies Resources; 5 Women-Empowerment A Bibliography Complied by Meena Usmani & Akhlaq Ahmed March 2015 CENTRE FOR WOMEN’S DEVELOPMENT STUDIES 25, Bhai Vir Singh Marg (Gole Market) New Delhi-110 001 Ph. 91-11-32226930, 322266931 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.cwds.ac.in/library/library.htm 1 PREFACE The “Women’s Studies Resources Series” is an attempt to highlight the various aspect of our specialized library collection relating to women and development studies. The documents available in the library are in the forms of books and monographs, reports, reprints, conferences Papers/ proceedings, journals/ newsletters and newspaper clippings. The present bibliography on "Women-Empowerment ” especially focuses on women’s political, social or economic aspects. It covers the documents which have empowerment in the title. To highlight these aspects, terms have been categorically given in the Subject Keywords Index. The bibliography covers the documents upto 2014 and contains a total of 1541 entries. It is divided into two parts. The first part contains 800 entries from books, analytics (chapters from the edited books), reports and institutional papers while second part contains over 741 entries from periodicals and newspapers articles. The list of periodicals both Indian and foreign is given as Appendix I. The entries are arranged alphabetically under personal author, corporate body and title as the case may be. For easy and quick retrieval three indexes viz. Author Index containing personal and institutional names, Subject Keywords Index and Geographical Area Index have been provided at the end. We would like to acknowledge the support of our colleagues at Library. -

International Journal of Diabetes in Developing Countries Incorporating Diabetes Bulletin

International Journal of Diabetes in Developing Countries Incorporating Diabetes Bulletin Founder Editors Late M. M. S. Ahuja Hemraj B. Chandalia, Department of Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism, Jaslok Hospital and Research Center, Mumbai Editor-in-Chief S.V. Madhu, Department of Endocrinology, University College of Medical Sciences-GTB Hospital, Delhi Executive Editor Rajeev Chawla, North Delhi Diabetes Centre, Delhi Associate Editors Amitesh Aggarwal, Department of Medicine, University College of Medical Sciences & GTB Hospital, Delhi, India Sudhir Bhandari, Department of Medicine, SMS Medical College and Hospital, Jaipur, India Simmi Dube, Department of Medicine, Gandhi Medical College & Hamidia Hospital Bhopal, MP, India Sujoy Ghosh, Department of Endocrinology, Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research, Kolkata, India Arvind Gupta, Department of Internal Medicine and Diabetes, Jaipur Diabetes Research Centre, Jaipur, India Sunil Gupta, Sunil’s Diabetes Care n' Research Centre Pvt. Ltd., Nagpur, India Viswanathan Mohan, Madras Diabetes Research Foundation, Chennai, India Krishna G. Seshadri, Sri Balaji Vidyapeeth, Chennai, India Saurabh Srivastava, Department of Medicine, Government Institute of Medical Sciences, Greater Noida, India Vijay Viswanathan, MV Hospital for Diabetes and Prof M Viswanthan Diabetes Research Centre Chennai, India Statistical Editors Amir Maroof Khan, Community Medicine, University College of Medical Sciences and GTB Hospital, Delhi Dhananjay Raje, CSTAT Royal Statistical Society, London, -

Form IEPF-1 2010-2011 FINAL

Read the following instructions carefully before proceeding to enter the Investor Details: (i)Install the pre-requisite softwares to proceed. The path for the same is as follows: MCA Portal >> Investor Services >> IEPF >> IEPF Application >> Prerequisite Software (ii) Upload the excel file in the format xls only Important Note (iii) Do not make any changes in the excel format/sheet name. Also do not delete any tab/sheet in the file PLEASE NOTE: 1) Kindly ensure that Summation of amounts in the excel(s) should be equal to that in IEPF Form, else your excel shall get rejected. 2) Kindly ensure that AGM Date in the excel(s) should be same as in IEPF Form, else your excel shall get rejected. Steps to follow to fill details in the 'Investor Details' tab. It is important that you Enable Macro using following instructions : Enable Macros a) Excel 2000 and 2003: Tools-->Macro-->Security-->Select 'Low'-->OK b) Excel 2007: Office Button-->Excel Options-->Trust Center-->Trust Center Settings--Macro Settings-->Enable all Macros-->OK Pl Note : Close the Excel Sheet and re-open it after enabling Macro to start. Enter the CIN (i) Enter the CIN in the excel (cell B2) (ii) Click on "Prefill" button (iii) Company Name will be automatically filled on click of prefill button . User need not enter it. (i) Fill in the required details in Columns A to P for Investor Details (row 15 onwards) (ii) Follow the below mentioned validations for filling in the details. First Name -> Mandatory if 'Last Name' is blank and Length should be less or equal to 35 characters. -

List of Common Service Centres Established in Uttar Pradesh

LIST OF COMMON SERVICE CENTRES ESTABLISHED IN UTTAR PRADESH S.No. VLE Name Contact Number Village Block District SCA 1 Aram singh 9458468112 Fathehabad Fathehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 2 Shiv Shankar Sharma 9528570704 Pentikhera Fathehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 3 Rajesh Singh 9058541589 Bhikanpur (Sarangpur) Fatehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 4 Ravindra Kumar Sharma 9758227711 Jarari (Rasoolpur) Fatehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 5 Satendra 9759965038 Bijoli Bah Agra Vayam Tech. 6 Mahesh Kumar 9412414296 Bara Khurd Akrabad Aligarh Vayam Tech. 7 Mohit Kumar Sharma 9410692572 Pali Mukimpur Bijoli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 8 Rakesh Kumur 9917177296 Pilkhunu Bijoli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 9 Vijay Pal Singh 9410256553 Quarsi Lodha Aligarh Vayam Tech. 10 Prasann Kumar 9759979754 Jirauli Dhoomsingh Atruli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 11 Rajkumar 9758978036 Kaliyanpur Rani Atruli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 12 Ravisankar 8006529997 Nagar Atruli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 13 Ajitendra Vijay 9917273495 Mahamudpur Jamalpur Dhanipur Aligarh Vayam Tech. 14 Divya Sharma 7830346821 Bankner Khair Aligarh Vayam Tech. 15 Ajay Pal Singh 9012148987 Kandli Iglas Aligarh Vayam Tech. 16 Puneet Agrawal 8410104219 Chota Jawan Jawan Aligarh Vayam Tech. 17 Upendra Singh 9568154697 Nagla Lochan Bijoli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 18 VIKAS 9719632620 CHAK VEERUMPUR JEWAR G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 19 MUSARRAT ALI 9015072930 JARCHA DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 20 SATYA BHAN SINGH 9818498799 KHATANA DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 21 SATYVIR SINGH 8979997811 NAGLA NAINSUKH DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 22 VIKRAM SINGH 9015758386 AKILPUR JAGER DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 23 Pushpendra Kumar 9412845804 Mohmadpur Jadon Dankaur G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 24 Sandeep Tyagi 9810206799 Chhaprola Bisrakh G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. -

GIPE-208819-Contents.Pdf (10.25Mb)

THE BOOK At the Census of India, in 1881, an attempt was lll3de to obtain the materials for a complete list of all Castes and Tribes as 1 eturned by the. people themselves .and ente red by the Census Enumerators in their Schedutes. Instructions were sent to .each Province and Native State directing that the number of each Caste recorded, .and the composition of each Caste by sex should be shown in the .:final report. In this manner it was designed to lay "a foundation for further research into the little l-nown subject of Caste," a subject .in inquiring into which investigators have been gravelled, not for lack of matter but from its abundance and complexity, and the lack of all rational arran~ment. The subject as a whole has indeed been a mighty maze without a plan. An inquirer .into the social habits and customs of a Caste in nne district h.a.s always been liable to the .subse quent dis.covery that the people whom he had met were but offshoots or wanderers from a larger Tribe whose home was in another province. The distinctive habits and customs of a people are of course always freshest and most marked where the mass of that people dwell : and when a detachment wanders away or splits off from the parent Tribe and settles elsewhere, it suffers, notwithstanding its Caste-conserv ancy. a certain change through the moul ding influence of superior numbers around. Hence the desideratum of a bird'.s-eye view of the entire system of Castes and Tribes found in India : and this, as far as tlteir strength and distribution go, is what 1 have tried to supply in this Compendium. -

Revenue Generated from Consultancy During the Last Five Years 2016-17 Sr. No. Name of the Teacher Consultant Name of Consultancy

Revenue generated from consultancy during the last five years 2016-17 Sr. Name of the teacher Name of consultancy project Consulting/Sponsoring agency Year Revenue Supporting No. consultant with contact details generated (INR document in Lakhs) 1 J P Ruparelia Enivronment Audit Deepak Nitrate Ltd Mr Kaushik 2016-17 3.893 Click Here Manji, Plot No 12/B, Dahej GIDC, Bharuch (+91)(2641)291495 & 9723432969 kkmanji@deepaknitritecom 2 J P Ruparelia Enivronment Audit Torrent Energy Ltd Plot No Mr S K 2016-17 4.1643 Click Here Sharma Z/9, Dahej SEZ, Bharuch 02642612045 & 9227593422 sksharma@torrentpowercom 3 J P Ruparelia Enivronment Audit Shree Vadodara Dist Co Op 2016-17 1.4879 Click Here Sugarcane Growers Union Ltd Mr Anilkumar Dwivedi, At & Post Gandhara, Taluka: Karjan, Vadodara wvasu33@gmailcom 9687673480 (02666)-290195 4 V J Lakhera Determine Thermal Polybond Insulation Pvt Ltd, Block 2016-17 0.37 Click Here Conductivity value 56(A), Plot No 17, Nehru Nagar, (W) Bhillai Dist Durg Chattisgarh, India 490020 5 U V Dave Cube Comppressive Strength Maruti Infracon, Ahmedabad Mr 2016-17 0.01 Click Here Krunal Prajapati (9016677288) 6 J P Ruparelia Enivronment Audit Jay Chemical Industries Limited 2016-17 0.88554 Click Here (Unit – 3/2) (Old Name: J H Kharawala (Unit – II) Mr Pankaj Kumar, Jay Chemical Industries Limited (Unit – 3/2) (Old Name: J H Kharawala (Unit – II), Plot No: 220, GIDC Phase - II Vatva, Ahmedabad – 382445, 9099912778 pankajkumar@jaychemicalcom 7 Hasan Rangwala school building soil Nirma Vidyavihar, Chharodi 2016-17 0.238 Click -

Patiala District, Punjab

GLOS3AHY OF CAS'rE NAIVllid RE'fURNED AT TH~ CEI'4SUS O}t' 1951 IN THE DISrRICTS OF PEPSU -_FOREWORD----_ .... ---- ..... __.... At the Oensus of 1951 there was a limited enumeration and tabulation of castes. Under the limited enumeration caste was recorded as returned by the respondent. Several complications arose out of this procedure. Many persons who returned their caste by generic or synonymous Scheduled Caste or tribe names not found in the prescribed lists were left out of the count of Scheduled Castes and Tribes and are-count had to be later ordered in some states. The Backward Classes Commission could not be provided with the 1951 population of individual castes and tribes or their individua~ educational and economic characteristics. 2. If a complete enumeration of castes is ordered at the next census much preliminary study will have to be carried out in order to ensure correct and rational enumeration and tabulation. For that purpose and, in fact, for any systematic enumeration of castes, a glossary of caste names as returned at the 1951 Census would be invaluable. This explains the prepara~ion of t~is glossary. 3. The Glossary has been prepared by running through all the male slips relating to the non-backward classes and the five per cent sample male slips of Backward Classes and sh~uld, therefore, be a complete list of caste names. All caste names as found in the slips have been deliberately included in the Glossary without any attempt at rationalisation. Many of these names are synonymous; some relate to sub-castes or gotras; and some are only generic names. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Sr.N O. Candidate Address Mobile No Landli

BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION M.P. BHOPAL LIST OF SELECTED CANDIDATES FOR CENTRAL SECTOR SCHOLARSHIP 2011-12 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Sr.N Candidate Name And Landli Institute Name Bank Name And Address With Bank Entitlem o.Roll No Candidate Address Mobile No ne And Address Code And IFSC Number Bank A/C No ent No. Amount File Name SATSANG NAGAR BANSAL KUTHLA PANNA INSTITUDE STATE BANK MOD KATNI RESERCHE OF INDIA TEH.KATNI,KATNI- AND SHAHNAGAR Science APOORVA 483501,Madhya TECHNOLOGY DISTT-PANNA General 1 217219891 KANKANE Pradesh 9755079707 NULL BHOPAL (MP) 3508 SBIN0003508 31906840544 11-1 10000 Merit SBI IIT PAWAI ASHIRWAD GUPTA BRANCH AADI ROOM NO 193 SANKRACHHA HOSTEL NO 3IIIT RYA MARG BOMBAY NEAR IIT MAIN Science ASHIRWAD PAWAI,BOMBAY- IIT BOMBEY GET PAWAJ General 2 211519302 GUPTA 400076,Maharashtra 0762066360 NULL PAWAI MS MUMBAI 01109 SBIN0001109 20091088843 11-2 10000 Merit BANK OF INFRONT OF BIHAJI BARODA, JI TEMPLE, CHOWK CHOWK BAZAR,CHHATARPU 07682 BAZAR Science SRAJAN R-471001,Madhya 24785 IET, DAVV CHHATARPUR General 3 212215102 KHARE Pradesh 8871782942 0 INDORE MP 012 BARB0000012 09590100011536 11-3 10000 Merit WARD NO 7 KHANGARAYA MUHAL BANSAL MAHARAJPUR,CHHA INSTITUTE OF STATE BANK TARPUR- SCIENCE AND OF INDIA, Science ABHILASHA 471501,Madhya TECHNOLOGY, PIPLANI General 4 212217974 SAHU Pradesh 8962169193 NULL BHOPAL BHOPAL 30442 SBIN0030442 20102505043 11-4 10000 Merit NEAR OF BOHRA MASZID RAJA BANK OF MOHALLA BARODA OPP HOSHANGABAD,HOS HOME GUARD HANGABAD- OFFICE Science RACHANA 461001,Madhya UIT RGPV HOSHANGABA HOSH BARB0HOSHA General 5 216722857 SHARMA Pradesh 7489055354 NULL BHOPAL D AN N 30080100003865 11-5 10000 Merit Page 1 BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION M.P. -

Ethnography : Castes and Tribes

िव�ा �सारक मंडळ, ठाणे Title : Ethnography : Caste and Tribes Author : Baines, Athelstane Publisher : Strassburg : Verlang Von Karl J. Trubner Publication Year : 1912 Pages : 231 pgs. गणपुस्त �व�ा �सारत मंडळाच्ा “�ंथाल्” �तल्पा्गर् िनिमर्त गणपुस्क िन�म्ी वषर : 2014 गणपुस्क �मांक : 101 ^ k^ Grundriss der Indo-arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde (ENCYCLOPEDIA OF INDO-ARYAN RESEARCH) BEGRUNDET VON G. BUHLER, FORTGESETZT VON F. KIELHORN, HERAUSGEGEBEN VON H. LUDERS UND J. WACKERNAGEL. II. BAND, 5. HEFT. ETHNOGRAPHY (CASTES AND TRIBES) BY SIR ATHELSTANE BAINES WITH A LIST OF THE MORE IMPORTANT WORKS ON INDIAN ETHNOGRAPHY BY W. SIEGLING. ^35^- STRASSBURG VERLAG VON KARL J. TRUBNER 1912. M. DuMout Schauberg, StraCburg. 6RUNDRISS DER INDO-ARISCHEN PHILOLOGIE UND ALTERTUMSKUNDE (ENCYCLOPEDIA OF INDO-ARYAN RESEARCH) BEGRiJNDET VON G. BUHLER, FORTGESETZT VON F. KIELHORN, HERAUSGEGEBEN VON H. LUDERS UND J. WACKERNAGEL. II. BAND, 5. HEFT. ETHNOGRAPHY (CASTES AND TRIBES) BY SIR ATHELSTANE BAINES. INTRODUCTION. § I. The subject with which it is proposed to deal in the present work is that branch of Indian ethnography which is concerned with the social organisation of the population, or the dispersal of the latter into definite groups based upon considerations of race, tribe, blood or oc- cupation. In the main, it takes the form of a descriptive survey of the return of castes and tribes obtained through the Census of 1901. The scope of the review, however, is limited to the population of India properly so called, and does not, therefore, include Burma or the outlying tracts of Baliichistan, Aden and the Andamans, by the omission of which the population dealt with is reduced from 294 to 283 millions. -

Social Transformation of Pakistan Under Kashmir Dispute

Social Transformations in Contemporary Society, 2019 (7) ISSN 2345-0126 (online) SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION OF PAKISTAN UNDER KASHMIR DISPUTE Sohaib Mukhtar National University of Malaysia, Malaysia [email protected] Abstract Kashmir dispute is the most important issue between India and Pakistan as they have fought three major wars and two conflicts since 1947. Kashmir dispute arose when British India was separated into Pakistan and India on 15th August 1947 under Indian Independence Act 1947. Independent Indian States could accede either to Pakistan or India as on 26th October 1947, Hari Singh signed treaty of accession with Indian Government while the Governor General of India Mountbatten remarked that after clearance from insurgency, plebiscite would take place in the state and people of Kashmir would decide either to go with Pakistan or India. During war of Kashmir in 1947, India went to the United Nations (UN) and asked for mediation. The UN passed resolution on 20th January 1948 to assist peaceful resolution of Kashmir dispute as another resolution was passed on 21st April 1948 for organization of plebiscite in Kashmir. India holds 43% of the region, Pakistan holds 37% and remaining 19% area is controlled by China. Dispute of Kashmir is required to be resolved through mediation under UN resolutions. Purpose – This research is an analysis of Kashmir dispute under the light of historical perspective, law passed by British Parliament and UN resolutions to clarify Kashmir dispute and recommend its solution under the light of UN resolutions. Design/methodology/approach – This study is routed in qualitative method of research to analyze Kashmir dispute under the light of relevant laws passed by British Parliament, historical perspective, and resolutions passed by the UN.