Air Quality in Ontario 2016 Report 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ELECTORAL DISTRICTS Proposal for the Province of Ontario Published

ELECTORAL DISTRICTS Proposal for the Province of Ontario Published pursuant to the Electoral Boundaries Readjustment Act Table of Contents Preamble ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Process for Electoral Readjustment ................................................................................................ 3 Notice of Sittings for the Hearing of Representations .................................................................... 4 Requirements for Making Submissions During Commission Hearings ......................................... 5 Rules for Making Representations .................................................................................................. 6 Reasons for the Proposed Electoral Boundaries ............................................................................. 8 Schedule A – Electoral District Population Tables....................................................................... 31 Schedule B – Maps, Proposed Boundaries and Names of Electoral Districts .............................. 37 2 FEDERAL ELECTORAL BOUNDARIES COMMISSION FOR THE PROVINCE OF ONTARIO PROPOSAL Preamble The number of electoral districts represented in the House of Commons is derived from the formula and rules set out in sections 51 and 51A of the Constitution Act, 1867. This formula takes into account changes to provincial population, as reflected in population estimates in the year of the most recent decennial census. The increase -

The Historical Development of Agricultural Policy and Urban Planning in Southern Ontario

Settlement, Food Lands, and Sustainable Habitation: The Historical Development of Agricultural Policy and Urban Planning in Southern Ontario By: Joel Fridman A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Geography, Collaborative Program in Environmental Studies Department of Geography and Program in Planning University of Toronto © Copyright by Joel Fridman 2014 Settlement, Food Lands, and Sustainable Habitation: The Historical Development of Agricultural Policy and Urban Planning in Southern Ontario Joel Fridman Masters of Arts in Geography, Collaborative Program in Environmental Studies Department of Geography and Program in Planning University of Toronto 2014 Abstract In this thesis I recount the historical relationship between settlement and food lands in Southern Ontario. Informed by landscape and food regime theory, I use a landscape approach to interpret the history of this relationship to deepen our understanding of a pertinent, and historically specific problem of land access for sustainable farming. This thesis presents entrenched barriers to landscape renewal as institutional legacies of various layers of history. It argues that at the moment and for the last century Southern Ontario has had two different, parallel sets of determinants for land use operating on the same landscape in the form of agricultural policy and urban planning. To the extent that they are not purposefully coordinated, not just with each other but with the social and ecological foundations of our habitation, this is at the root of the problem of land access for sustainable farming. ii Acknowledgements This thesis is accomplished with the help and support of many. I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Harriet Friedmann, for kindly encouraging me in the right direction. -

On Target for Stroke Prevention and Care

Ontario Stroke Evaluation Report 2014 On Target for Stroke Prevention and Care SUPPLEMENT: ONTARIO STROKE REPORT CARDS June 2014 ONTARIO STROKE EVALUATION REPORT 2014: ON TARGET FOR STROKE PREVENTION AND CARE Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences ONTARIO STROKE EVALUATION REPORT 2014: ON TARGET FOR STROKE PREVENTION AND CARE Ontario Stroke Evaluation Report 2014 On Target for Stroke Prevention and Care SUPPLEMENT: ONTARIO STROKE REPORT CARDS Authors Ruth Hall, PhD Beth Linkewich, MPA, BScOT, OT Reg (Ont) Ferhana Khan, MPH David Wu, PhD Jim Lumsden, BScPT, MPA Cally Martin, BScPT, MSc Kay Morrison, RN, MScN Patrick Moore, MA Linda Kelloway, RN, MN, CNN(c) Moira K. Kapral, MD, MSc, FRCPC Christina O’Callaghan, BAppSc (PT) Mark Bayley, MD, FRCPC Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences i ONTARIO STROKE EVALUATION REPORT 2014: ON TARGET FOR STROKE PREVENTION AND CARE Publication Information Contents © 2014 Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences INSTITUTE FOR CLINICAL EVALUATIVE SCIENCES 1 ONTARIO STROKE REPORT CARDS (ICES). All rights reserved. G1 06, 2075 Bayview Avenue Toronto, ON M4N 3M5 32 APPENDICES This publication may be reproduced in whole or in Telephone: 416-480-4055 33 A Indicator Definitions part for non-commercial purposes only and on the Email: [email protected] 35 B Methodology condition that the original content of the publication 37 C Contact Information for High-Performing or portion of the publication not be altered in any ISBN: 978-1-926850-50-4 (Print) Facilities and Sub-LHINs by Indicator way without the express written permission ISBN: 978-1-926850-51-1 (Online) 38 D About the Organizations Involved in this Report of ICES. -

JOURNEY a Communicator for the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Kingston

JOURNEY A Communicator for the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Kingston April 2017 www.romancatholic.kingston.on.ca Photo by Gary Tranmer Friends in faith: Msgr. Don Clement, who passed away on Wednesday, March 15th, is seen here with three of his friends – all of whom had a special role in his Funeral Mass, which was held at St. Mary’s Cathedral on Tuesday, March 21st. From left to right, Msgr. Joe Lynch, who gave the homily; Sister Pauline Lally, SP, who did the First Read- ing; Msgr. Clement; and Monica Heine, who was the cantor, song leader, and soloist. This picture was taken in July of 2016 at the time of Monica’s swearing-in ceremony as Crown Attorney for the County of Lennox and Addington. Monsignor Donald Patrick Clement: This ‘Gentle Priest’ will be Greatly Missed Throngs of mourners gathered at St. Mary’s Cathedral on March 20th and 21st for the Visitation, Vigil Service, and Funeral Mass of Monsignor Don Clement, the beloved former rector of St. Mary’s Cathedral, who passed away on March 15th at the age of 89. Msgr. Clement, a native of Prescott, received an Engineering degree from Queen’s University before being ordained to the priesthood in 1961. He served as Associate Pastor at St. John’s and St. Joseph’s Parishes (1961-1972); and as Pastor at Holy Family Parish (1972-1984), and at Blessed Sacrament Parish, Amherstview (1984-1990), before being appointed Rector of St. Mary’s Cathedral, a position which he held until his retirement in 2005. He was named a Prel- ate of Honour in 1990, and held several administrative positions in the Archdiocese of Kingston: Dean of the Central Deanery, member of the College of Consultors, and member of both the Personnel Committee and the Finance Com- mittee. -

Rank of Pops

Table 1.3 Basic Pop Trends County by County Census 2001 - place names pop_1996 pop_2001 % diff rank order absolute 1996-01 Sorted by absolute pop growth on growth pop growth - Canada 28,846,761 30,007,094 1,160,333 4.0 - Ontario 10,753,573 11,410,046 656,473 6.1 - York Regional Municipality 1 592,445 729,254 136,809 23.1 - Peel Regional Municipality 2 852,526 988,948 136,422 16.0 - Toronto Division 3 2,385,421 2,481,494 96,073 4.0 - Ottawa Division 4 721,136 774,072 52,936 7.3 - Durham Regional Municipality 5 458,616 506,901 48,285 10.5 - Simcoe County 6 329,865 377,050 47,185 14.3 - Halton Regional Municipality 7 339,875 375,229 35,354 10.4 - Waterloo Regional Municipality 8 405,435 438,515 33,080 8.2 - Essex County 9 350,329 374,975 24,646 7.0 - Hamilton Division 10 467,799 490,268 22,469 4.8 - Wellington County 11 171,406 187,313 15,907 9.3 - Middlesex County 12 389,616 403,185 13,569 3.5 - Niagara Regional Municipality 13 403,504 410,574 7,070 1.8 - Dufferin County 14 45,657 51,013 5,356 11.7 - Brant County 15 114,564 118,485 3,921 3.4 - Northumberland County 16 74,437 77,497 3,060 4.1 - Lanark County 17 59,845 62,495 2,650 4.4 - Muskoka District Municipality 18 50,463 53,106 2,643 5.2 - Prescott and Russell United Counties 19 74,013 76,446 2,433 3.3 - Peterborough County 20 123,448 125,856 2,408 2.0 - Elgin County 21 79,159 81,553 2,394 3.0 - Frontenac County 22 136,365 138,606 2,241 1.6 - Oxford County 23 97,142 99,270 2,128 2.2 - Haldimand-Norfolk Regional Municipality 24 102,575 104,670 2,095 2.0 - Perth County 25 72,106 73,675 -

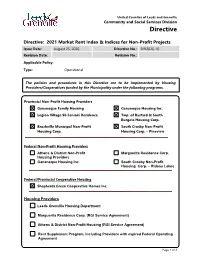

2021 Market Rent Index & Indices for Non-Profit Projects

United Counties of Leeds and Grenville Community and Social Services Division Directive Directive: 2021 Market Rent Index & Indices for Non-Profit Projects Issue Date: August 25, 2020 Directive No.: DIR2020-10 Revision Date: Revision No.: Applicable Policy: Type: Operational The policies and procedures in this Directive are to be implemented by Housing Providers/Cooperatives funded by the Municipality under the following programs. Provincial Non-Profit Housing Providers Gananoque Family Housing Gananoque Housing Inc. Legion Village 96 Seniors Residence Twp. of Bastard & South Burgess Housing Corp. Brockville Municipal Non-Profit South Crosby Non-Profit Housing Corp. Housing Corp. – Pineview Federal Non-Profit Housing Providers Athens & District Non-Profit Marguerita Residence Corp. Housing Providers Gananoque Housing Inc. South Crosby Non-Profit Housing Corp. – Rideau Lakes Federal/Provincial Cooperative Housing Shepherds Green Cooperative Homes Inc. Housing Providers Leeds Grenville Housing Department Marguerita Residence Corp. (RGI Service Agreement) Athens & District Non-Profit Housing (RGI Service Agreement) Rent Supplement Program, including Providers with expired Federal Operating Agreement Page 1 of 3 United Counties of Leeds and Grenville Community and Social Services Division Directive Directive: 2021 Market Rent Index & Indices for Non-Profit Projects Issue Date: August 25, 2020 Directive No.: DIR2020-10 Revision Date: Revision No.: BACKGROUND Each year, the Ministry provides indices for costs and revenues to calculate subsidies under the Housing Services Act (HSA). The indices to be used for 2021 are contained in this directive. PURPOSE The purpose of this directive is to advise housing providers of the index factors to be used in the calculation of subsidy for 2021. ACTION TO BE TAKEN Housing providers shall use the index factors in the table below to calculate subsidies under the Housing Services Act, 2011 (HSA) on an annual basis. -

The North York East LIP Strategic Plan and Report

The North York East LIP Strategic Plan and Report The North York East Strategic Plan has been developed around six areas of focus: Information & Outreach; Civic Engagement; Collaboration & Capacity Building; Language Training & Supports; Labour Market; and Health Services.Six working groups will be established to address these areas of focus. In- depth directions for each working group are outlined in the main body of this report Executive Summary In 2009, Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC), in partnership with the Ontario Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration, launched Local Immigration Partnership (LIP) projects throughout Ontario. LIPs were developed as research initiatives to identify ways to coordinate and enhance local service delivery to newcomers across the province, while promoting efficient use of resources. In October 2009, Working Women Community Centre entered an agreement with CIC to lead a LIP project in the North York East area of Toronto. The North York East LIP is located in the far north of the city, contained by Steeles Avenue to the north, Highway 401 to the south, Victoria Avenue East to the east and the Don Valley River to the west. The area population is almost 80,000, 70% of which are immigrants to Canada. A major priority for the North York East LIP project was to root its research in the real-life experiences of local newcomers and local community organizations. In total, over 400 newcomers & immigrants, and over 100 service providers were consulted and engaged with to identify challenges, solutions and new directions for the settlement sector in the area. Methods of engagement for both newcomers and service providers included focus group research, key-informant interviews, community consultations and advisory panel workshops. -

Area 83 Eastern Ontario International Area Committee Minutes June 2

ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS AREA 83 EASTERN ONTARIO INTERNATIONAL Area 83 Eastern Ontario International Area Committee Minutes June 2, 2018 ACM – June 2, 2018 1 ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS AREA 83 EASTERN ONTARIO INTERNATIONAL 1. OPENING…………………………………………………………………………….…………….…4 2. REVIEW AND ACCEPTANCE OF AGENDA………………………………….…………….…...7 3. ROLL CALL………………………………………………………………………….……………….7 4. REVIEW AND ACCEPTANCE OF MINUTES OF September 9, 2017 ACM…………………7 5. DISTRICT COMMITTEE MEMBERS’ REPORTS ……………………………………………....8 District 02 Malton……………………………………………………………………………….…….. 8 District 06 Mississauga……………………………………………………………………….…….. 8 District 10 Toronto South Central…………………………………………………………….….…. 8 District 12 Toronto South West………………………………………………………………….…. 9 District 14 Toronto North Central………………………………………………………………..….. 9 District 16 Distrito Hispano de Toronto…………………………………………………….………..9 District 18 Toronto City East……………………………………………………………………........9 District 22 Scarborough……………………………………………………………………………… 9 District 26 Lakeshore West………………………………………………………………….……….10 District 28 Lakeshore East……………………………………………………………………………11 District 30 Quinte West…………………………………………………………………………….. 11 District 34 Quinte East……………………………………………………………………………… 12 District 36 Kingston & the Islands……………………………………………………………….… 12 District 42 St. Lawrence International………………………………………………………………. 12 District 48 Seaway Valley North……………………………………………………………….……. 13 District 50 Cornwall…………………………………………………………………………………… 13 District 54 Ottawa Rideau……………………………………………………………………………. 13 District 58 Ottawa Bytown…………………………………………………………………………… -

Toronto North & East Office Market Report

Fourth Quarter 2019 / Office Market Report Toronto North & East Photo credit: York Region Quick Stats Collectively, the Toronto North and East office with 66,500 sf – lifting the overall market and 11.6% markets finished the fourth quarter and 2019 offsetting losses in the Yorkdale and Dufferin Overall availability rate in Toronto in positive territory. Combined occupancy and Finch nodes. SmartCentres’ mixed-use North, vs. 10.2% one year ago levels increased 358,000 square feet (sf) PWC-YMCA tower on Apple Mill Rd. in the with class B buildings in the East and class A Vaughan Metropolitan Centre (103,000 sf 10% buildings in the North making up the bulk of office space) opened for occupancy in Vaughan sublet available space of the gain. Quarter-over-quarter, overall November with PWC taking possession of four as a percentage of total available availability rose 30 basis points (bps) to 11.9%, floors (77,000 sf) for 230-plus employees. space while vacancy held steady at 7.2%. Available sublet space also remained flat, at 903,000 sf, The North market’s overall availability 190,800 sf as gains in the East market balanced losses jumped 130 bps quarter-over-quarter to Total new office area built in the 11.6% and sits 140 bps higher than one year Toronto North and East markets in the North. The East had an exceptionally during 2019 – all in Vaughan strong showing in 2019, as occupancy ago. This was largely attributed to RioCan increased 455,000 sf year-over-year. It was also REIT marketing a 99,000-sf contiguous block 5 a year of big lease transactions including: Bell over six floors (currently occupied by BMO Buildings with largest contiguous Canada (445,000 sf), Scotiabank (406,000 sf), Financial) at 4881 Yonge St. -

Freedom Liberty

2013 ACCESS AND PRIVACY Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner Ontario, Canada FREEDOM & LIBERTY 2013 STATISTICS In free and open societies, governments must be accessible and transparent to their citizens. TABLE OF CONTENTS Requests by the Public ...................................... 1 Provincial Compliance ..................................... 3 Municipal Compliance ................................... 12 Appeals .............................................................. 26 Privacy Complaints .......................................... 38 Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA) .................................. 41 As I look back on the past years of the IPC, I feel that Ontarians can be assured that this office has grown into a first-class agency, known around the world for demonstrating innovation and leadership, in the fields of both access and privacy. STATISTICS 4 1 REQUESTS BY THE PUBLIC UNDER FIPPA/MFIPPA There were 55,760 freedom of information (FOI) requests filed across Ontario in 2013, nearly a 6% increase over 2012 where 52,831 were filed TOTAL FOI REQUESTS FILED BY JURISDICTION AND RECORDS TYPE Personal Information General Records Total Municipal 16,995 17,334 34,329 Provincial 7,029 14,402 21,431 Total 24,024 31,736 55,760 TOTAL FOI REQUESTS COMPLETED BY JURISDICTION AND RECORDS TYPE Personal Information General Records Total Municipal 16,726 17,304 34,030 Provincial 6,825 13,996 20,821 Total 23,551 31,300 54,851 TOTAL FOI REQUESTS COMPLETED BY SOURCE AND JURISDICTION Municipal Provincial Total -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

Historical Outlines of Railways in Southwestern Ontario

UCRS Newsletter • July 1990 Toronto & Guelph Railway Note: The Toronto & Goderich Railway Company was estab- At the time of publication of this summary, Pat lished in 1848 to build from Toronto to Guelph, and on Scrimgeour was on the editorial staff of the Upper to Goderich, on Lake Huron. The Toronto & Guelph Canada Railway Society (UCRS) newsletter. This doc- was incorporated in 1851 to succeed the Toronto & ument is a most useful summary of the many pioneer Goderich with powers to build a line only as far as Guelph. lines that criss-crossed south-western Ontario in the th th The Toronto & Guelph was amalgamated with five 19 and early 20 centuries. other railway companies in 1854 to form the Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada. The GTR opened the T&G line in 1856. 32 - Historical Outlines of Railways Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada in Southwestern Ontario The Grand Trunk was incorporated in 1852 with au- BY PAT SCRIMGEOUR thority to build a line from Montreal to Toronto, assum- ing the rights of the Montreal & Kingston Railway Company and the Kingston & Toronto Railway Com- The following items are brief histories of the railway pany, and with authority to unite small railway compa- companies in the area between Toronto and London. nies to build a main trunk line. To this end, the follow- Only the railways built in or connecting into the area ing companies were amalgamated with the GTR in are shown on the map below, and connecting lines in 1853 and 1854: the Grand Trunk Railway Company of Toronto, Hamilton; and London are not included.