Report of the Task Force on the Establishment of a Truth, Justice and Reconciliation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Election Violence in Kenya

Spontaneous or Premeditated? DISCUSSION PAPER 57 SPONTANEOUS OR PREMEDITATED? Post-Election Violence in Kenya GODWIN R. MURUNGA NORDISKA AFRIKAINSTITUTET, UppSALA 2011 Indexing terms: Elections Violence Political violence Political crisis Ethnicity Democratization Kenya The opinions expressed in this volume are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. Language checking: Peter Colenbrander ISSN 1104-8417 ISBN 978-91-7106-694-7 © The author and Nordiska Afrikainstitutet 2011 Production: Byrå4 Print on demand, Lightning Source UK Ltd. Spontaneous or Premeditated? Contents Contents ..............................................................................................................................................................3 Foreword .............................................................................................................................................................5 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................7 Post-Election Violence: Overview of the Literature .............................................................................8 A Note on the Kenyan Democratisation Processes ............................................................................13 Clash of Interpretations ................................................................................................................................17 The Ballot Box and -

“Not Worth the Risk” Threats to Free Expression Ahead of Kenya’S 2017 Elections

“Not Worth the Risk” Threats to Free Expression Ahead of Kenya’s 2017 Elections HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH “Not Worth the Risk” Threats to Free Expression Ahead of Kenya’s 2017 Elections Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-34761 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org ARTICLE 19 Eastern Africa is an independent not-for profit organization that promotes freedom of expression and access to information as a fundamental human right as well as an empowerment right. ARTICLE 19 Eastern Africa was registered in Kenya in 2007 as an affiliate of ARTICLE 19 international. ARTICLE 19 Eastern African has over the past 10 years implemented projects that included policy and legislative advocacy on media and access to information laws and review of public service media policies and regulations. The organization has also implemented capacity building programmes for journalists on safety and protection and for a select civil society organisation to engage with United Nations (UN) and African Union (AU) mechanisms in 14 countries in Eastern Africa. -

Kenya: “Place of Sharīʿa in the Constitution”

PART THREE KENYA: “PLACE OF SHARĪʿA IN THE CONSTITUTION” Halkano Abdi Wario - 9789004262126 Downloaded from Brill.com09/25/2021 07:52:30AM via free access Map 5 Map of Kenya: Showing principal places referred to in Part Three Halkano Abdi Wario - 9789004262126 Downloaded from Brill.com09/25/2021 07:52:30AM via free access CHAPTER SEVEN DEBATES ON KADHI’S COURTS AND CHRISTIAN-MUSLIM RELATIONS IN ISIOLO TOWN: THEMATIC ISSUES AND EMERGENT TRENDS Halkano Abdi Wario Introduction Since 1992, Kenya has been characterised by demands for new consti- tutional dispensations. It has also seen heightened competing interests emerge in which religion and politicised ethnicity have played a pivotal role in the political game of the day. The same scenario has been replicated at a grass roots level. Elsewhere, as in the Kenyan case, the increased calls for recognition and empowerment of courts applying aspects of sharīʿa almost instantly elicit strong negative responses from Christian communi- ties. One of the contentious issues in the referendum on a draft constitu- tion was the issue of Kadhi’s courts. Should they be empowered, or left to stay as in the current Constitution? The resultant debates are the concern of this chapter. The findings of the research have strong implications for Christian-Muslim relations. The chapter examines how different views evolved in Isiolo, a small Northern Kenyan town. The town has a his- tory of strained Christian-Muslim relations. Contests over resources and ownership of the town feature highly in every new conflict. The chapter explores the role of ethno-religious ascriptions and elite mobilization in the increasing misunderstandings about Kadhi’s courts. -

The Post-Election Violence and Mediation 1. the Announcement Of

Bureau du Procureur Office of the Prosecutor The Post‐Election Violence and Mediation 1. The announcement of the results of the 27 December 2007 general election in Kenya triggered widespread violence, resulting in the deaths of over a thousand people, thousands of people being injured, and several hundreds of thousands of people being displaced from their homes. 2. On 28 February 2008, international mediation efforts led by Kofi Annan, Chair of the African Union Panel of Eminent African Personalities, resulted in the signing of a power‐ sharing agreement between Mwai Kibaki as President and Raila Odinga as Prime‐Minister. The agreement, also established three commissions: (1) the Commission of Inquiry on Post‐Election Violence (CIPEV); (2) the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission; and (3) the Independent Review Commission on the General Elections held in Kenya on 27 December 2007. 3. On 15 October 2008 CIPEV‐ also known as the Waki Commission, published its Final Report. The Report recommended the establishment of a special tribunal to seek accountability against persons bearing the greatest responsibility for crimes relating toe th 2007 General Elections in Kenya, short of which, the Report recommended forwarding the information it collected to the ICC. Efforts to Establish a Local Tribunal 4. On 16 December 2008, President Kibaki and Prime Minister Odinga agreed to implement the recommendations of the Waki Commission and specifically to prepare and submit a Bill to the National Assembly to establish the Special Tribunal. Yet, on 12 February 2009, the Kenyan Parliament failed to adopt the “Constitution of Kenya (Amendment) Bill 2009” which was necessary to ensure that the Special Tribunal would be in accordance with the Constitution. -

Parliament of Kenya the Senate

October 15, 2013 SENATE DEBATES 1 PARLIAMENT OF KENYA THE SENATE THE HANSARD Tuesday, 15th October, 2013 The Senate met at the Kenyatta International Conference Centre at 2.30 p.m. [The Speaker (Hon. Ethuro) in the Chair] PRAYERS QUORUM CALL AT COMMENCEMENT OF SITTING The Speaker (Hon. Ethuro): Do we have a quorum? (The Speaker consulted the Clerk-at-the Table) I am informed we have a quorum. Let us commence business. ADMINISTRATION OF OATH Sen. Mbuvi: Mr. Speaker, Sir, may I introduce to the House the newly nominated Senator, Njoroge Ben, from The National Alliance Party (TNA), under the Jubilee Coalition, which is the ruling Coalition in the Republic of Kenya. Sen. Njoroge is ready to take the Oath of Office. The Speaker (Hon. Ethuro): Let us proceed. The Oath of Allegiance was administered to:- Njoroge Ben (Applause) Sen. Ong’era: Mr. Speaker, Sir, may I present to you the newly nominated Member of the Senate, Omondi Godliver Nanjira. Godliver is from the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM), as you know, the most popular party in Kenya. (Laughter) Hon. Senators: Ndiyo! Wambie. The Speaker (Hon. Ethuro): Proceed. Disclaimer: The electronic version of the Senate Hansard Report is for information purposes only. A certified version of this Report can be obtained from the Hansard Editor, Senate. October 15, 2013 SENATE DEBATES 2 The Oath of Allegiance was administered to:- Omondi Godliver Nanjira (Applause) The Speaker (Hon. Ethuro): Hon. Senators, as Sen. Nanjira is settling down, I would like us to give them a round of applause in our usual way. -

Kenya: on the Brink of Disaster

writenet is a network of researchers and writers on human rights, forced migration, ethnic and political conflict WRITENET writenet is the resource base of practical management (uk) e-mail: [email protected] independent analysis KENYA: ON THE BRINK OF DISASTER A Writenet Report by Gérard Prunier commissioned by United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Emergency Preparedness and Response Section - EPRS May 2009 Caveat: Writenet papers are prepared mainly on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. The papers are not, and do not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. The views expressed in the paper are those of the author and are not necessarily those of Writenet or Practical Management. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction........................................................................................1 2 Social and Economic Unrest .............................................................1 3 The Security Situation .......................................................................4 3.1 Border Issues ................................................................................................4 3.2 Internal Security ..........................................................................................5 4 Confrontation Civil Society/Political Establishment......................7 4.1 The Waki Report..........................................................................................7 -

(KTDA) – Corruption – Kikuyu Ethnic Group

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: KEN34521 Country: Kenya Date: 16 March 2009 Keywords: Kenya – Kenya Tea Development Agency (KTDA) – Corruption – Kikuyu ethnic group This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide any information regarding the directorship of the Kenya Tea Agency. 2. Please provide information on the structure and activities of the Kenya Tea Development Agency (KTDA). 3. Are there any reports of fraud charges against the management of the KTDA? 4. Is there anything to indicate that managers of tea cartels or figures prominent in the tea industry have been elected to parliament in Kenya? 5. Please provide any information on corruption in the tea industry in Kenya. 6. Please provide any information on government involvement in corruption in the tea industry. 7. To what extent is the KTDA involved in combating corruption? 8. Are there any reports of people being killed or otherwise seriously harmed as a result of advocating reform in the tea industry? 9. What steps have the Kenyan authorities taken to address corruption in the tea industry or other industries? 10. -

Sbw A.1 – 18.1.2010 Record of Meeting of The

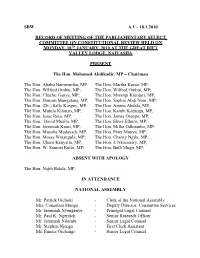

SBW A.1 – 18.1.2010 RECORD OF MEETING OF THE PARLIAMENTARY SELECT COMMITTEE ON CONSTITUTIONAL REVIEW HELD ON MONDAY, 18 TH JANUARY, 2010 AT THE GREAT RIFT VALLEY LODGE, NAIVASHA PRESENT The Hon. Mohamed Abdikadir, MP – Chairman The Hon. Ababu Namwamba, MP; The Hon. Martha Karua, MP; The Hon. Wilfred Ombui, MP; The Hon. Wilfred Ombui, MP; The Hon. Chachu Ganya, MP; The Hon. Mwangi Kiunjuri, MP; The Hon. Danson Mungatana, MP; The Hon. Sophia Abdi Noor, MP; The Hon. (Dr.) Sally Kosgey, MP; The Hon. Amina Abdala, MP; The Hon. Mutula Kilonzo, MP; The Hon. Kambi Kazungu, MP; The Hon. Isaac Ruto, MP; The Hon. James Orengo, MP; The Hon. David Musila, MP; The Hon. Ekwe Ethuro, MP; The Hon. Jeremiah Kioni, MP; The Hon. Millie Odhiambo, MP; The Hon. Musalia Mudavadi, MP; The Hon. Peter Munya, MP; The Hon. Moses Wetangula, MP; The Hon. Charity Ngilu, MP; The Hon. Uhuru Kenyatta, MP; The Hon. J. Nkaisserry, MP; The Hon. W. Samoei Rutto, MP; The Hon. Beth Mugo, MP; ABSENT WITH APOLOGY The Hon. Najib Balala, MP; IN ATTENDANCE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY Mr. Patrick Gichohi - Clerk of the National Assembly Mrs. Consolata Munga - Deputy Director, Committee Services Mr. Jeremiah Nyengenye - Principal Legal Counsel Mr. Paul K. Ngentich - Senior Research Officer Mr. Jeremiah Ndombi - Senior Legal Counsel Mr. Stephen Njenga - First Clerk Assistant Ms. Eunice Gichangi - Senior Legal Counsel Mr. Michael Karuru - Legal Counsel Ms. Mary Mwathi - Hansard Reporter Mr. Said Waldea - Hansard Report Mr. Zakayo Mogere - Second Clerk Assistant Mr. Samuel Njoroge - Second Clerk Assistant Ms. Rose Mudibo - Public Relations Officer (Prayers) (The meeting convened at 9.30 p.m.) The Clerk of the National Assembly (Mr. -

The Kenya General Election

AAFFRRIICCAA NNOOTTEESS Number 14 January 2003 The Kenya General Election: senior ministerial positions from 1963 to 1991; new Minister December 27, 2002 of Education George Saitoti and Foreign Minister Kalonzo Musyoka are also experienced hands; and the new David Throup administration includes several able technocrats who have held “shadow ministerial positions.” The new government will be The Kenya African National Union (KANU), which has ruled more self-confident and less suspicious of the United States Kenya since independence in December 1963, suffered a than was the Moi regime. Several members know the United disastrous defeat in the country’s general election on December States well, and most of them recognize the crucial role that it 27, 2002, winning less than one-third of the seats in the new has played in sustaining both opposition political parties and National Assembly. The National Alliance Rainbow Coalition Kenyan civil society over the last decade. (NARC), which brought together the former ethnically based opposition parties with dissidents from KANU only in The new Kibaki government will be as reliable an ally of the October, emerged with a secure overall majority, winning no United States in the war against terrorism as President Moi’s, fewer than 126 seats, while the former ruling party won only and a more active and constructive partner in NEPAD and 63. Mwai Kibaki, leader of the Democratic Party (DP) and of bilateral economic discussions. It will continue the former the NARC opposition coalition, was sworn in as Kenya’s third government’s valuable mediating role in the Sudanese peace president on December 30. -

Decolonising Accidental Kenya Or How to Transition to a Gameb Society,The Anatomy of Kenya Inc: How the Colonial State Sustains

Pandora Papers: The Kenyatta’s Secret Companies By Africa Uncensored Published by the good folks at The Elephant. The Elephant is a platform for engaging citizens to reflect, re-member and re-envision their society by interrogating the past, the present, to fashion a future. Follow us on Twitter. Pandora Papers: The Kenyatta’s Secret Companies By Africa Uncensored President Uhuru Kenyatta’s family, the political dynasty that has dominated Kenyan politics since independence, for many years secretly owned a web of offshore companies in Panama and the British Virgin Islands, according to a new leak of documents known as the Pandora Papers. The Kenyattas’ offshore secrets were discovered among almost 12 million documents, largely made up of administrative paperwork from the archives of 14 law firms and agencies that specialise in offshore company formations. Other world leaders found in the files include the King of Jordan, the prime minister of the Czech Republic Andrej Babiš and Gabon’s President Ali Bongo Ondimba. The documents were obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and seen by more than 600 journalists, including reporters at Finance Uncovered and Africa Uncensored, as part of an investigation that took many months and spanned 117 countries. Though no reliable estimates of their net worth have been published, the Kenyattas are regularly reported to be one of the richest families in the country. The Kenyattas’ offshore secrets were discovered among almost 12 million documents, largely made up of administrative paperwork from the archives of 14 law firms and agencies that specialise in offshore company formations. -

Chapter One Introduction

Chapter One Introduction Imagine trying to cover Northern Ireland‟s troubles without using the words „Protestant‟ or „Catholic‟. Or reporting Iraq without referring to „Shias‟ and „Sunnis‟. The attempt would be absurd, the result unfathomable. And yet, in Kenya‟s post-electoral crisis, that is exactly what much of the local media doggedly tried to do. When we read an account in a British newspaper of shack-dwellers being evicted from a Nairobi slum, or see on the BBC gangs attacking inhabitants in the Rift Valley, we are usually told whether these are Kikuyus fleeing Luos, or Kalenjins attacking Kikuyus. But, in Kenya, this particular spade is almost never called a spade. No, it‟s "a certain metal implement". The "problem of tribalism" may be obsessively debated, the gibe of "tribalist" thrown with reckless abandon at politicians and community leaders, but it is just not done to identify a person‟s tribe in the media. The results, given a crisis in which the expression of long-running grievances has taken the most explicit ethnic form, can be opaque. When Mr Maina Kiai, chairman of the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights, addressed displaced people in Eldoret earlier this year, he was booed and heckled. Kenyan media reported the incident without explaining why. The answer was that the displaced he met were mostly Kikuyus, and Kiai, a vocal Kikuyu critic of a Kikuyu-led Government, is regarded by many as a traitor to his tribe. Sometimes, the outcome is simply bizarre. When one newspaper ran a vox pop in January, one entry was meant to capture vividly the predicament of a 15-year-old girl of mixed parentage. -

1952-2010: Prospects and Challenges of the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission Under the 2010 Constitution James T

Loyola University Chicago, School of Law LAW eCommons Faculty Publications & Other Works 2011 Kenya’s Long Anti-Corruption Agenda: 1952-2010: Prospects and Challenges of the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission Under the 2010 Constitution James T. Gathii Loyola University Chicago, School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/facpubs Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation James T. Gathii, Kenya’s Long Anti-Corruption Agenda: 1952-2010: Prospects and Challenges of the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission Under the 2010 Constitution, 4 L. & Dev. Rev. 182 (2011) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kenya’s Long Anti-Corruption Agenda - 1952-2010: Prospects and Challenges of the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission Under the 2010 Constitution James Thuo Gathii Associate Dean for Research and Scholarship and Governor George E. Pataki Professor of International Commercial Law, Albany Law School ([email protected]) Draft November 27, 2010 1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Part I: Initial Steps in the Fight against Corruption ...................................................................................... 6