A Variational Approach to Eulerian Geometry Processing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Algorithm for the Construction of Intrinsic Delaunay Triangulations with Applications to Digital Geometry Processing

An Algorithm for the Construction of Intrinsic Delaunay Triangulations with Applications to Digital Geometry Processing Matthew Fisher Boris Springborn Peter Schroder¨ Alexander I. Bobenko Caltech TU Berlin Caltech TU Berlin Abstract The discrete Laplace-Beltrami operator plays a prominent role in many Digital Geometry Processing applications ranging from de- noising to parameterization, editing, and physical simulation. The standard discretization uses the cotangents of the angles in the im- mersed mesh which leads to a variety of numerical problems. We advocate the use of the intrinsic Laplace-Beltrami operator. It sat- isfies a local maximum principle, guaranteeing, e.g., that no flipped triangles can occur in parameterizations. It also leads to better con- ditioned linear systems. The intrinsic Laplace-Beltrami operator is based on an intrinsic Delaunay triangulation of the surface. We detail an incremental algorithm to construct such triangulations to- gether with an overlay structure which captures the relationship be- tween the extrinsic and intrinsic triangulations. Using a variety of example meshes we demonstrate the numerical benefits of the in- trinsic Laplace-Beltrami operator. Figure 1: Left: carrier of the (cat head) surface as defined by the original embedded mesh. Right: the intrinsic Delaunay triangu- 1 Introduction lation of the same carrier. Delaunay edges which appear in the original triangulation are shown in white. Some of the original 2 Delaunay triangulations of domains in R play an important role edges are not present anymore (these are shown in black). In their in many numerical computing applications because of the quality stead we see red edges which appear as the result of intrinsic flip- guarantees they make, such as: among all triangulations of the con- ping. -

Geometry-Aware Topological Decompositions of Meshes

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Geometry-aware topological decompositions of meshes Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3vh0q7wn Author Chen, Jia Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Geometry-aware topological decompositions of meshes DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Computer Science by Jia Chen Dissertation Committee: Professor Gopi Meenakshisundaram, Chair Professor Aditi Majumder Professor Shuang Zhao 2019 Chapter3 c 2016 ACM New York, NY, USA Chapter3 c 2018 ACM New York, NY, USA All other materials c 2019 Jia Chen DEDICATION To my family \. a man who keeps company with glaciers comes to feel tolerably insignificant by and by." { Mark Twain, A Tramp Abroad ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURESv LIST OF TABLESx LIST OF ALGORITHMS xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xii CURRICULUM VITAE xiii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION xiv 1 Introduction1 1.1 Cycles of topological properties.........................2 1.2 Topological decompositions of meshes......................4 2 Definitions and Background7 2.1 Surfaces and their topological classification...................7 2.2 Primal graph and dual graph embedded on a surface.............8 2.3 Paths and cycles.................................9 2.4 Tunnel and handle cycles............................. 11 3 Iterative localization of handle and tunnel cycles 13 3.1 Related work................................... 14 3.2 Problem formulation............................... 15 3.3 Localizing handle and tunnel cycles....................... 16 3.3.1 Iterative tree-cotree algorithm...................... 16 3.3.2 Cycle tightening.............................. 20 3.3.3 Decoupling composite fundamental cycles............... -

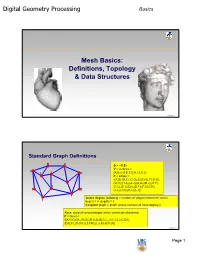

Digital Geometry Processing Mesh Basics

Digital Geometry Processing Basics Mesh Basics: Definitions, Topology & Data Structures 1 © Alla Sheffer Standard Graph Definitions G = <V,E> V = vertices = {A,B,C,D,E,F,G,H,I,J,K,L} E = edges = {(A,B),(B,C),(C,D),(D,E),(E,F),(F,G), (G,H),(H,A),(A,J),(A,G),(B,J),(K,F), (C,L),(C,I),(D,I),(D,F),(F,I),(G,K), (J,L),(J,K),(K,L),(L,I)} Vertex degree (valence) = number of edges incident on vertex deg(J) = 4, deg(H) = 2 k-regular graph = graph whose vertices all have degree k Face: cycle of vertices/edges which cannot be shortened F = faces = {(A,H,G),(A,J,K,G),(B,A,J),(B,C,L,J),(C,I,L),(C,D,I), (D,E,F),(D,I,F),(L,I,F,K),(L,J,K),(K,F,G)} © Alla Sheffer Page 1 Digital Geometry Processing Basics Connectivity Graph is connected if there is a path of edges connecting every two vertices Graph is k-connected if between every two vertices there are k edge-disjoint paths Graph G’=<V’,E’> is a subgraph of graph G=<V,E> if V’ is a subset of V and E’ is the subset of E incident on V’ Connected component of a graph: maximal connected subgraph Subset V’ of V is an independent set in G if the subgraph it induces does not contain any edges of E © Alla Sheffer Graph Embedding Graph is embedded in Rd if each vertex is assigned a position in Rd Embedding in R2 Embedding in R3 © Alla Sheffer Page 2 Digital Geometry Processing Basics Planar Graphs Planar Graph Plane Graph Planar graph: graph whose vertices and edges can Straight Line Plane Graph be embedded in R2 such that its edges do not intersect Every planar graph can be drawn as a straight-line plane graph © -

Evolution of the Graphical Processing Unit

University of Nevada Reno Evolution of the Graphical Processing Unit A professional paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science with a major in Computer Science by Thomas Scott Crow Dr. Frederick C. Harris, Jr., Advisor December 2004 Dedication To my wife Windee, thank you for all of your patience, intelligence and love. i Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor Dr. Harris for his patience and the help he has provided me. The field of Computer Science needs more individuals like Dr. Harris. I would like to thank Dr. Mensing for unknowingly giving me an excellent model of what a Man can be and for his confidence in my work. I am very grateful to Dr. Egbert and Dr. Mensing for agreeing to be committee members and for their valuable time. Thank you jeffs. ii Abstract In this paper we discuss some major contributions to the field of computer graphics that have led to the implementation of the modern graphical processing unit. We also compare the performance of matrix‐matrix multiplication on the GPU to the same computation on the CPU. Although the CPU performs better in this comparison, modern GPUs have a lot of potential since their rate of growth far exceeds that of the CPU. The history of the rate of growth of the GPU shows that the transistor count doubles every 6 months where that of the CPU is only every 18 months. There is currently much research going on regarding general purpose computing on GPUs and although there has been moderate success, there are several issues that keep the commodity GPU from expanding out from pure graphics computing with limited cache bandwidth being one. -

Computer Graphics CMU 15-462/15-662 Scotty 3D Setup Recitation Today! Hunt Library Computer Lab 3:30-5Pm

Digital Geometry Processing Computer Graphics CMU 15-462/15-662 Scotty 3D setup recitation Today! Hunt Library Computer Lab 3:30-5pm CMU 15-462/662 Last time part 1: overview of geometry Many types of geometry in nature Geometry Demand sophisticated representations Two major categories: - IMPLICIT - “tests” if a point is in shape - EXPLICIT - directly “lists” points Lots of representations for both CMU 15-462/662 Last time part 2: Meshes & Manifolds Mathematical description of geometry - simplifying assumption: manifold - for polygon meshes: “fans, not fins” Data structures for surfaces - polygon soup - halfedge mesh - storage cost vs. access time, etc. Today: next how do we manipulate geometry? twin - face edge - geometry processing / resampling Halfedge vertex CMU 15-462/662 Today: Geometry Processing & Queries Extend traditional digital signal processing (audio, video, etc.) to deal with geometric signals: - upsampling / downsampling / resampling / filtering ... - aliasing (reconstructed surface gives “false impression”) Also ask some basic questions about geometry: - What’s the closest point? Do two triangles intersect? Etc. Beyond pure geometry, these are basic building blocks for many algorithms in graphics (rendering, animation...) CMU 15-462/662 Digital Geometry Processing: Motivation 3D Scanning 3D Printing CMU 15-462/662 Geometry Processing Pipeline scan print process CMU 15-462/662 Geometry Processing Tasks reconstruction filtering remeshing parameterization compression shape analysis CMU 15-462/662 Geometry Processing: Reconstruction -

Creating and Processing 3D Geometry

Creating and processing 3D geometry Marie-Paule Cani [email protected] Cédric Gérot [email protected] Franck Hétroy [email protected] http://evasion.imag.fr/Membres/Franck.Hetroy/Teaching/Geo3D/ Context: computer graphics ● We want to represent objects – Real objects – Virtual/created objects ● Several ways for virtual object creation – Interactive by graphists – Automatic from real data ● 3D scanner, medical angiography, ... – Procedural (on the fly) ● Complex scenes, terrain, ... ● Different uses – Display, animation, ph ysical simulation, ... Course overview 1.Objects representations – Volume/surface, implicit/explicit, ... Real-time triangulation of implicit surfaces Course overview 1.Objects representations – Volume/surface, implicit/explicit, ... 2.Geometry processing – Simplify, smooth, ... Interactive multiresolution surface exploration Course overview 1.Objects representations – Volume/surface, implicit/explicit, ... 2.Geometry processing – Simplify, smooth, ... 3.Virtual object creation – Surface reconstruction, interactive modeling Shape modeling by sketching Planning (provisional) Part I – Geometry representations ● Lecture 1 – Oct 9th – FH – Introduction to the lectures; point sets, meshes, discrete geometry. ● Lecture 2 – Oct 16th – MPC – Parametric curves and surfaces; subdivision surfaces. ● Lecture 3 – Oct 23rd - MPC – Implicit surfaces. Planning (provisional) Part II – Geometry processing ● Lecture 4 – Nov 6th – FH – Discrete differential geometry; mesh smoothing and simplification (paper presentations). -

Research on Shape Mapping of 3D Mesh Models Based on Hidden

Research on Shape Mapping of 3D Mesh Models based on Hidden Markov Random Field and EM Algorithm WANG Yong1 WU Huai-yu2 1 (University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China) 2 (Institute of Automation, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100080, China) Abstract How to establish the matching (or corresponding) between two different 3D shapes is a classical problem. This paper focused on the research on shape mapping of 3D mesh models, and proposed a shape mapping algorithm based on Hidden Markov Random Field and EM algorithm, as introducing a hidden state random variable associated with the adjacent blocks of shape matching when establishing HMRF. This algorithm provides a new theory and method to ensure the consistency of the edge data of adjacent blocks, and the experimental results show that the algorithm in this paper has a great improvement on the shape mapping of 3D mesh models. Keywords Shape Mapping, 3D Mesh Model, Hidden Markov Random Field, EM Algorithm 1 Introduction bending deformation, different sampling rate, and Digital geometry processing of 3D mesh models different parameterization methods. (a1'/a2', b1'/b2') has broad application prospects in the fields of are the transformed models of (a1/a2, b1/b2) by the industrial design, virtual reality, game entertainment, geometry processing framework of global Internet, digital museum, urban planning and so on[1]. perspective. It can be seen that the transformed However the surface of 3D mesh models is usually models are much similar in their poses and shapes. bent arbitrarily, lack of continuous parameters, and So the difficulty of establishing the automatic has complex characterized details, as is quite different matching between two different 3D shapes has been from the regular 2D image data with the uniform greatly reduced. -

Computer Graphics CMU 15-462/15-662

Digital Geometry Processing Computer Graphics CMU 15-462/15-662 Last time: Meshes & Manifolds Mathematical description of geometry - simplifying assumption: manifold - for polygon meshes: “fans, not fns” Data structures for surfaces - polygon soup - halfedge mesh - storage cost vs. access time, etc. Today: next how do we manipulate geometry? twin - face edge - geometry processing / resampling Halfedge vertex CMU 15-462/662 Today: Geometry Processing Extend traditional digital signal processing (audio, video, etc.) to deal with geometric signals: - upsampling / downsampling / resampling / fltering ... - aliasing (reconstructed surface gives “false impression”) Beyond pure geometry, these are basic building blocks for many areas/algorithms in graphics (rendering, animation...) CMU 15-462/662 Digital Geometry Processing: Motivation 3D Scanning 3D Printing CMU 15-462/662 Geometry Processing Pipeline scan print process CMU 15-462/662 Geometry Processing Tasks reconstruction filtering remeshing parameterization compression shape analysis CMU 15-462/662 Geometry Processing: Reconstruction Given samples of geometry, reconstruct surface What are “samples”? Many possibilities: - points, points & normals, ... - image pairs / sets (multi-view stereo) - line density integrals (MRI/CT scans) How do you get a surface? Many techniques: - silhouette-based (visual hull) - Voronoi-based (e.g., power crust) - PDE-based (e.g., Poisson reconstruction) - Radon transform / isosurfacing (marching cubes) CMU 15-462/662 Geometry Processing: Upsampling Increase resolution -

Topology Preserving Isosurface Extraction for Geometry Processing

Topology Preserving Isosurface Extraction for Geometry Processing Gokul Varadhan1, Shankar Krishnan2, TVN Sriram1, and Dinesh Manocha1 1Department of Computer Science, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, U.S.A 2AT&T Labs - Research, Florham Park, New Jersey, U.S.A http://gamma.cs.unc.edu/recons ABSTRACT Marching Cubes (MC) [2] or any of its variants [3–5]. We We address the problem of computing a topology preserving refer to these isosurface extraction algorithms collectively as isosurface from a volumetric grid using Marching Cubes for MC-like algorithms. The output of an MC-like algorithm is geometry processing applications. We present a novel adap- an approximation – usually a polygonal approximation – of tive subdivision algorithm to generate a volumetric grid. the implicit surface. We refer to this step as reconstruction Our algorithm ensures that every grid cell satisfies certain of the implicit surface. sampling criteria. We show that these sampling criteria Compared to other surface representations (e.g. para- are sufficient to ensure that the isosurface extracted from metric surfaces), implicit surface representations are easy to the grid using Marching Cubes is topologically equivalent use to perform geometric operations like union, intersection, to the exact isosurface: both the exact isosurface and the difference, blending, and warping. Specifically, they map extracted isosurface have the same genus and connectivity. Boolean operations into simple minimum/maximum opera- We use our algorithm for accurate boundary evaluation of tions on the scalar fields of the primitives. Suppose we have Boolean combinations of polyhedra and low degree algebraic two primitives P1 and P2 with scalar fields f1 and f2. -

Geometry Processing Algorithms

Geometry Processing Algorithms CSCS468468 http: //cs468.stfdd/tanford.edu/ Mirela Ben Chen Objective • Theory and algorithms for efficient analysis and manipulation of complex 3D models • Hands-on experience 2 Requirements Prerequisites: - Experience with C++ programming - Background in geometry or computational geometry helpful, but not necessary. Grade (3 units): - Programming exercises - OpenMesh intro (10%) - Surface smoothing (20%) - Simplification (20%) - Parameterization (25%) - Remeshing (25%) Use OpenMesh API Sign up to Piazza! 3 References • Book “Polygon Mesh Processing” by Mario Botsch, Leif Kobbelt, Mark Pauly, Pierre Alliez, Bruno Levy • Eurographics 2008 course notes “Geometric Modeling Based on Polygonal Meshes” by Mario Botsch, Mark Pauly, Leif Kobbelt, Pierre Alliez, Bruno Levy, Stephan Bischoff, Christian Rössl • More links on web site 4 What is Geometry Processing About? • Acquiring • Analyzing • Manipulating 5 Applications Medical E-Commerce Simulation Engineering Culture Games & Movies Architecture Architecture Creating Reverse Engineering 6 A Geometry Processing Pipeline Low Level Algorithms 7 A Geometry Processing Pipeline 8 A Geometry Processing Pipeline High Level Algorithms Deformation and editing Extracting shape structure 9 Acquiring 33DD Geometry RSRange Scanners 10 Acquiring 33DD Geometry RSRange Scanners 11 Acquiring 33DD Geometry Tomography Simplification 20,000 8,000 2,000 Demo Applications Multi-resolution hierarchies for – efficient geometry processing – level-of-detail (()LOD) renderin g 14 Size-Quality -

Challenges & Opportunities for 3D Graphics on the PC

ChallengesChallenges && OpportunitiesOpportunities forfor 3D3D GraphicsGraphics onon thethe PCPC Neil Trevett, VP Marketing 3Dlabs President, Web3D Consortium www.3dlabs.com © Copyright 3Dlabs, 1999 - Page 1 - PROPRIETARY & CONFIDENTIAL Topics Graphics Challenges on the PC Platform • What is going to be the killer 3D application? - No-one cares about 3D other than workstations applications and gamers - What is going to change that - on the PC and on the Web? • Geometry processing performance - How to push to the next level of performance i.e. >40M polygons/sec - CPUs are not fast enough - we need geometry acceleration ... - … but high-end volumes are too small to warrant specialized chip development • PC system bandwidth - passing data to the graphics engine - Front side bus bandwidth is a fundamental barrier to polygon performance today - What are the possible hardware and software solutions? • Graphics memory architecture - On-board texture management is an unbounded problem and a difficult software problem - UMA memory is cheap - but lacks high performance - Has the time come for memory management in graphics chips? © Copyright 3Dlabs, 1999 - Page 2 3Dlabs Industrial-strength boards for design professionals • The pioneer in bringing professional-class 3D to the PC - The first 3D chip on the PC: the GLINT 300SX in 1994 - First integrated 3D setup chip: the GLINT Delta in 1996 - First integrated geometry and lighting chip: the GLINT Gamma in 1997 • Have been shipping professional 3D for over 15 years - Licensed IRIS GL from SGI before -

Spectral Geometry Processing with Manifold Harmonics

Author manuscript, published in "Computer Graphics Forum 27, 2 (2008) 251-260" DOI : 10.1111/j.1467-8659.2008.01122.x EUROGRAPHICS 2008 / G. Drettakis and R. Scopigno Volume 27 (2008), Number 2 (Guest Editors) Spectral Geometry Processing with Manifold Harmonics B. Vallet1 and B. Lévy1 1ALICE team, INRIA Abstract We present an explicit method to compute a generalization of the Fourier Transform on a mesh. It is well known that the eigenfunctions of the Laplace Beltrami operator (Manifold Harmonics) define a function basis allowing for such a transform. However, computing even just a few eigenvectors is out of reach for meshes with more than a few thousand vertices, and storing these eigenvectors is prohibitive for large meshes. To overcome these limitations, we propose a band-by-band spectrum computation algorithm and an out-of-core implementation that can compute thousands of eigenvectors for meshes with up to a million vertices. We also propose a limited-memory filtering algorithm, that does not need to store the eigenvectors. Using this latter algorithm, specific frequency bands can be filtered, without needing to compute the entire spectrum. Finally, we demonstrate some applications of our method to interactive convolution geometry filtering. These technical achievements are supported by a solid yet simple theoretic framework based on Discrete Exterior Calculus (DEC). In particular, the issues of symmetry and discretization of the operator are considered with great care. Categories and Subject Descriptors (according to ACM CCS): I.3.5 [Computer Graphics]: Computational Geometry and Object Modeling, Hierarchy and geometric transformations 1. Introduction the one described in [PG01] for point sets.