International Workshop on Processing and Marketing of Shea Products in Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adverse Reactions

Read this insert carefully before you start taking this medicine. This medicine is only intended for use by the qualified patient. It is illegal to transfer this product to another person. The “medical use” of marijuana does not include the use or administration of any form or amount of marijuana in a manner that is inconsistent with the qualified physician’s directions or physician certification. Keep this medicine out of the reach of children and pets, if consumed, contact a healthcare professional or poison control center. Clinical Pharmacology General Information GrowHealthy products primarily consist of a plant-based This insert is an educational aid; it does not cover all possible uses, cannabinoid compound named ∆-9-tetrahydrocannabinol precautions, side-effects, or interactions of this medicine and is not (THC). THC is known for its “psychoactive” effects that intended as medical advice for individual conditions. Seek immediate sometimes lead to the “high.” The onset, intensity, and medical attention if you think you are or may be suffering from any duration of these effects are related to the route from which medical condition. Never delay seeking medical advice, disregard it is administered in the body. Each patient should start at medical advice, or discontinue medical treatment because of a low dose and increase the dosage slowly, under a information you find here or provided to you by us. None of the physician’s guidance. It is advised to start or adjust the information contained herein is intended to be a suitable medical dosage of the medication under the observation of a diagnosis or construed as medical advice or recommended treatment. -

South Sudan Country Portfolio

South Sudan Country Portfolio Overview: Country program established in 2013. USADF currently U.S. African Development Foundation Partner Organization: Foundation for manages a portfolio of 9 projects and one Cooperative Agreement. Tom Coogan, Regional Director Youth Initiative Total active commitment is $737,000. Regional Director Albino Gaw Dar, Director Country Strategy: The program focuses on food security and Email: [email protected] Tel: +211 955 413 090 export-oriented products. Email: [email protected] Grantee Duration Value Summary Kanybek General Trading and 2015-2018 $98,772 Sector: Agro-Processing (Maize Milling) Investment Company Ltd. Location: Mugali, Eastern Equatoria State 4155-SSD Summary: The project funds will be used to build Kanybek’s capacity in business and financial management. The funds will also build technical capacity by providing training in sustainable agriculture and establishing a small milling facility to process raw maize into maize flour. Kajo Keji Lulu Works 2015-2018 $99,068 Sector: Manufacturing (Shea Butter) Multipurpose Cooperative Location: Kajo Keji County, Central Equatoria State Society (LWMCS) Summary: The project funds will be used to develop LWMCS’s capacity in financial and 4162-SSD business management, and to improve its production capacity by establishing a shea nut purchase fund and purchasing an oil expeller and related equipment to produce grade A shea butter for export. Amimbaru Paste Processing 2015-2018 $97,523 Sector: Agro-Processing (Peanut Paste) Cooperative Society (APP) Location: Loa in the Pageri Administrative Area, Eastern Equatoria State 4227-SSD Summary: The project funds will be used to improve the business and financial management of APP through a series of trainings and the hiring of a management team. -

Effect of Using Vegetable Oils - Shea Butter ( Vitellaria Paradoxa ) Oil and Coconut Oil As Waxing Material for Cucumber ( Cucumis Sativus L.) Fruits

Direct Research Journal of Agriculture and Food Science (DRJAFS) Vol.7 (6), pp. 122-130, June 2019 ISSN 2354-4147 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3236134 Article Number: DRJA3702965315 Copyright © 2019 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://directresearchpublisher.org/journal/drjafs/ Full Length Research Paper Effect of using Vegetable Oils - Shea Butter ( Vitellaria paradoxa ) Oil and Coconut Oil as Waxing Material for Cucumber ( Cucumis sativus L.) Fruits Tsado, 1* E. K., Adesina 1, O. A., Adediran 1, O. A., Saidu 1, A., Jiya 2, M. J. and Lawal 1, L. T. 1Department of Crop Production, Federal University of Technology Minna, Niger State, Nigeria. 2Department of Food Science, Federal University of Technology Minna, Niger State, Nigeria. *Corresponding Author E-mail: [email protected] Received 17 April 2019; Accepted 28 May, 2019 Cucumber fruits were coated with melted shea butter oil and and 18 DAS only. Through the study, shea butter oil (processed coconut oil by rubbing it around the fruits and stored for a period shea butter oil) among the others were excellent and was seen at of 18 days. The vegetable oils were used to brush the cucumber every point to be better than the coconut oil and local shea butter fruits. The control fruits were kept without any waxing material; waxed cucumber fruits. At the end of the study, it was found out the fruits were kept at ambient temperature on the laboratory that shea butter is good waxing material that can be used to coat bench for 3 weeks. During this period the weight and size of the any food material in order to increase its period of storage and fruits were determined at intervals of 3 days. -

Natural Cosmetic Ingredients Exotic Butters & Oleins

www.icsc.dk Natural Cosmetic Ingredients Exotic Butters & Oleins Conventional, Organic and Internal Stabilized Exotic Butters & Oleins Exotic Oils and butters are derived from uncontrolled plantations or jungles of Asia, Africa and South – Central America. The word exotic is used to define clearly that these crops are dependent on geographical and seasonal variations, which has an impact on their yearly production capacity. Our selection of natural exotic butters and oils are great to be used in the following applications: Anti-aging and anti-wrinkle creams Sun Protection Factor SPF Softening and hydration creams Skin brightening applications General skin care products Internal Stabilization I.S. extends the lifecycle of the products 20-30 times as compare to conventional. www.icsc.dk COCOA BUTTER Theobroma Cacao • Emollient • Stable emulsions and exceptionally good oxidative stability • Reduce degeneration and restores flexibility of the skin • Fine softening effect • Skincare, massage, cream, make-up, sunscreens CONVENTIONAL ORGANIC STABILIZED AVOCADO BUTTER Persea Gratissima • Skincare, massage, cream, make-up • Gives stables emulsions • Rapid absorption into skin • Good oxidative stability • High Oleic acid content • Protective effect against sunlight • Used as a remedy against rheumatism and epidermal pains • Emollient CONVENTIONAL ORGANIC STABILIZED ILLIPE BUTTER Shorea Stenoptera • Emollient • Fine softening effect and good spreadability on the skin • Stable emulsions and exceptionally good oxidative stability • Creams, stick -

Preliminary Assessment of Shea Butter Waxing on the Keeping and Sensory Qualities of Four Plantain (Musa Aab) Varieties

African Journal of Agricultural Research Vol. 5(19), pp. 2676-2684, 4 October, 2010 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/AJAR ISSN 1991-637X ©2010 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Preliminary assessment of shea butter waxing on the keeping and sensory qualities of four plantain (Musa aab) varieties 1* 2 2 3 I. Sugri , J. C. Norman , I. Egyir and P. N. T. Johnson 1Council of Scientific and Industrial Research CSIR-Savanna Agriculture Research Institute, P. O. Box 46, Manga- Bawku, Ghana. 2Department of Crop Science, University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana. 3Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR)-Food Research Institute, P. O. Box M32, Accra, Ghana. Accepted 30 July, 2010 Over the last few years, the production of plantain has been increasing due to the introduction of some high yielding varieties. Unfortunately, very high post-harvest losses are incurred annually due to lack of appropriate storage technologies. This study evaluated the effect of shea butter as a food-grade wax on the pre-climacteric life and sensory qualities of four plantain varieties (Apem, Apentu, Asamienu and Oniaba). Waxing was achieved by brushing shea butter on fruits surfaces. The fruit diameter before waxing (d1) and after waxing (d2) was measured and the difference (d2-d1) taken as the waxing thickness. Parameters assessed were the uniformity of ripening, gloss quality, incidence of off-flavours and disorders. Waxing thickness of 0.5 and 1 mm resulted in irregular ripening, green-soft disorder and off-flavours. However, thin layer waxing (<0.05mm) prolonged the pre-climacteric life to 22, 20, 17, and 15 days in Apem, Apentu, Oniaba and Asamienu respectively. -

Clarifying Mud Mask

This clarifying mask draws out dirt and Our Story congestion while helping absorb excess oil African Tamarind Tea Tree Sofi Tucker started selling Shea and improve the appearance of troubled skin. No Sulfates Black Soap Extract Oil ® Nuts at the village market A proprietary blend of African Black Soap in Bonthe, Sierra Leone in 1912. and Raw Shea Butter helps to clarify, balance By age 19, the widowed mother and soothe blemish-prone skin. Skin feels of four was selling Shea Butter, purified and refreshed. A natural A natural Clarifies No Parabens African Black Soap and her Apply a thin layer of mud with fingertips to remedy astringent skin with for oily, which helps naturally homemade hair and skin clean skin, avoiding eye area. Keep on for up preparations all over the to 10 minutes. Remove with damp face cloth. troubled exfoliate anti-septic No Phthalates AFRICAN BLACK SOAP countryside. Sofi Tucker was our Use weekly or as needed. skin. and brighten properties. skin. Grandmother and SheaMoisture Ingredients CLARIFYING is her legacy. With this purchase Deionized Water, Kaolin Clay, Bentonite Clay, African Black Soap, you help empower disadvantaged Simmondia Chinensis (Jojoba) Oil*, Sulfur, Vegetable Emulsifying No Propylene Glycol Wax, Butyrospermum Parkii (Shea Butter)*♥, Sodium Stearoyl MUD MASK women to realize a brighter, Lactylate, Butyl Avocadate (Avocado), Willow Bark Extract, w/ Tamarind Extract & Tea Tree Oil Gylcerine, Benzyl PCA, Salicylic Acid, Phytosterols, Panthenol healthier future. (Pro-Vitamin B-5), Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Bisabolol (Chamomile), Tea Tree Oil, Dehydroacetic Acid, Allantoin (Comfrey Root No Mineral Oil Extract), Tamarindus Indica (Tamarind) Extract, Olea Europea (Olive)Oil*, Spearmint Oil, Peppermint Oil, Eucalyptus Oil BLEMISH PRONE SKIN Sundial Brands LLC *Certified Organic Ingredient ♥Fair Trade Ingredient Natural ingredients may vary in color and consistency. -

A Art of Essential Oils

The Essence’s of Perfume Materials Glen O. Brechbill FRAGRANCE BOOKS INC. www.perfumerbook.com New Jersey - USA 2009 Fragrance Books Inc. @www.perfumerbook.com GLEN O. BRECHBILL “To my parents & brothers family whose faith in my work & abilities made this manuscript possible” II THE ESSENCES OF PERFUME MATERIALS © This book is a work of non-fiction. No part of the book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the author except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Please note the enclosed book is based on The Art of Fragrance Ingredients ©. Designed by Glen O. Brechbill Library of Congress Brechbill, Glen O. The Essence’s of Perfume Materials / Glen O. Brechbill P. cm. 477 pgs. 1. Fragrance Ingredients Non Fiction. 2. Written odor descriptions to facillitate the understanding of the olfactory language. 1. Essential Oils. 2. Aromas. 3. Chemicals. 4. Classification. 5. Source. 6. Art. 7. Thousand’s of fragrances. 8. Science. 9. Creativity. I. Title. Certificate Registry # 1 - 164126868 Copyright © 2009 by Glen O. Brechbill All Rights Reserved PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition Fragrance Books Inc. @www.perfumerbook.com THE ESSENCE’S OF PERFUME MATERIALS III My book displays the very best of essential oils. It offers a rich palette of natural ingredients and essences. At its fullest it expresses a passion for the art of perfume. With one hundred seventy-seven listings it condenses a great deal of pertinent information in a single text. -

COMBINE PRODUCT LIST.Xlsx

James Wild Herbs 2350, Chaowk , Tilak Bazar, Khali Baoli, Delhi-110006 Contact No:+91 9301345099, 9719054702 Email:- [email protected], [email protected] S.NO PRODUCT PRICE BUTTER COSMETIC SALT 8 Cashew Nut Oil 6000 S.NO PRODUCT PRICE S.NO PRODUCT PRICE 9 Castor Oil 350 1 Almond Butter 900 1 Sea Salt 320 10 Chirongi Oil 1650 2 Aloe Butter 1200 2 Rock Salt 160 11 Coconut Oil 350 3 Apricot Kernel Butter 1450 3 Arabian Sea Salt 255 12 Cotton Seed Oil 1850 4 Avocado Butter 1200 4 White Rock Salt 150 13 Dill Seed Oil 6000 5 Chaulmoogra Butter 1450 5 Grey Sea Salt 450 14 Elmi Oil 14000 6 Cocoa Butter 900 6 Bath Salt 400 15 Grape Fruit Oil 850 7 Cupuacu Butter 1350 7 Dead Sea Salt 450 16 Hazel Nut Oil 3600 8 Dhupu Butter 1250 8 Himalayan Pink Salt 125 17 Hemp Seed Oil 1450 9 Green Tea Butter 1260 9 Atlantic Bath Salt 410 18 Jojoba Oil 1850 10 Hemp Seed Butter 1230 10 Epsom Salt 90 19 Kalongi Oil 1800 11 Illipe Butter 1380 11 Persian Sapphire Blue Salt 490 20 Lin Seed Oil 450 12 Jojoba Butter 1250 21 Neem Oil 600 13 Kokum Butter 1050 22 Nutmeg Oil 600 14 Kukui Nut Butter 1650 23 Olive Oil 800 15 Macadamia Nut Butter 1260 24 Orange Oil 3600 COSMETIC SOAP BASE 16 Mango Butter 850 25 Papaya Oil 28000 17 Mowrah Butter 1250 S.NO PRODUCT PRICE 26 Pumpkin Seed Oil 1450 18 Murumuru Butter 1300 1 Aloevera Soap Base 175 27 Seasome Seed Oil 250 19 Papaya Butter 1420 2 Canola Soap Base 250 28 Sun Flower Oil 350 20 Peanut Butter 1450 3 Charcoal Soap Base 260 29 Till Oil 250 21 Sal Butter 1460 4 Coconut Soap Base 130 30 Tomer Seed Oil 2400 22 Shea Butter -

Herbal Salves Mini Lessons

Herbal Salves & Creams Natty’s face cream Cream = oil, water, emulsifier • 10 g bees wax • 15 g lanette wax • 25 g shea butter • 1 tsp coconut oil • 90 g water Instructions: Fill 1 pot with water and put a smaller pot inside the larger pot (double boiler method). Add ingredients according to the bullet point list below. Turn heat down according to your preference (if you see the ingredients are melting very fast, turn down the heat to steadily melt and mix ingredients). • Melt down wax (both), then shea butter • Add water + coconut oil • Mix all together (immersion blend or whip best) and let sit for 24 hours After your mix has set for a day add: • 50 g base cream (of choice – or whatever is available) • 25 g hydrosol (scent of choice – or whatever is available) • 10 mL oil (jojoba, grapeseed, olive, sunflower – oils that won’t be an allergen concern) • 30-40 drops essential oil (if desired) Blend all ingredients together and add to jars! Lip Balm 3 parts oil 1-part butter 1-part wax (2 types) + essential oils Oils = raw or infused oil of choice Butter = raw or infused Wax = 1-part bees wax 1-part lanette wax Instructions: • In a double boiler melt wax, then butter, then oil • Remove from heat, and add essential oils if desired • Pour into molds and let sit for 10 – 30 minutes before moving Ointment Ointment = wax, oil Bees wax = natural stabilizer, seals in moisture, protective layer • 75 mL Shea butter • 25 mL Infused oil • 20 g Bees wax • Few drops essential oil Instructions: Melt all ingredients – wax, shea butter, oil and mix together Body Butter Bars 2 parts oil (infused) 6 parts wax (bees) 4 parts butter (shea) Essential oil glitter (or silica) Ingredients: • 4 tsp calendula oil • 6 tsp bees wax • 5 tsp shea butter • 10-20 drops oil • ¼ tsp glitter Instructions: melt down wax, butter and oil. -

Product Safety Data Sheet

Product Safety Data Sheet Document D0124475 Versio 3.0 Code: n: Description: FIL,VEET,ALL Status: Published Project Silhouette Project 08074 Name: Numbe r: Category: Hair Removal Segme Cold Wax Strips nt: (Female) Formula FILL FORMULA Type: PSDS PSDS 1. PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION Product Name VEET ®COLD Cold WAXWax StripsSTRIPS for- FaceNORMAL and BikiniSKIN With Shea Butter (TDS 0117762) VEET COLD WAX STRIPS - NORMAL/DRY SKIN With Aloe Vera (TDS 0124059) VEET COLD WAX STRIPS - DRY SKIN With Aloe Vera (TDS 0124059) UPC Code VEET COLD WAX STRIPS - SENSITIVE SKIN With Vitamin E and Sweet Almond Oil (TDS 0124060) VEET62200-77338 COLD WAX STRIPS - FOR MEN With Aloe Vera (TDS 0124059) VEET COLD WAX STRIPS - FACE - NORMAL SKIN With Shea Butter - (TDS 0117762) VEETFormula COLD Number WAX STRIPS - FACE - SENSITIVE SKIN With Vitamin E and Sweet Almond Oil (TDS 0124060) VEET0124060 COLD WAX STRIPS - UNDERARM/BIKINI - NORMAL SKIN With Shea Butter - (TDS 0117762) VEET COLD WAX STRIPS - UNDERARM/BIKINI - SENSITIVE SKIN With Vitamin E and Sweet Almond Oil (TDS 0124060) VEET PERFECT FINISH WIPES (TDS 0051009) Product Type Depilatory waxes Validation Date Variants December 22nd, 2009 As above (product name) Use To remove unwanted body hair (wax) and wax residues (wipe) Appearance Skillet containing : cold wax strips + sachets with impregnated finishing wipe 01177620124060 -- NormalSensitive Skin Skin- Opaque - Golden pink brown colour colour with with fruity gourmande fragrance 0124059 - Dry Skin - Opaque green colour with floral fragrance 0124060 -

INCI Terminology

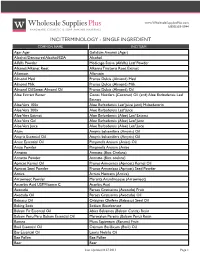

www.WholesaleSuppliesPlus.com 1(800)359-0944 INCI TERMINOLOGY - SINGLE INGREDIENT COMMON NAME INCI TERM Agar Agar Gelidium Amansii (Agar) Alcohol/Denatured Alcohol/SDA Alcohol Alfalfa Powder Medicago Sativa (Alfalfa) Leaf Powder Alkanet/Alkanet Root Alkanna Tinctoria Root Extract Allantoin Allantoin Almond Meal Prunus Dulcis (Almond) Meal Almond Milk Prunus Dulcis (Almond) Milk Almond Oil/Sweet Almond Oil Prunus Dulcis (Almond) Oil Aloe Extract Butter Cocos Nucifera (Coconut) Oil (and) Aloe Barbadensis Leaf Extract Aloe Vera 100x Aloe Barbadensis Leaf Juice (and) Maltodextrin Aloe Vera 200x Aloe Barbadensis Leaf Juice Aloe Vera Extract Aloe Barbadensis (Aloe) Leaf Extract Aloe Vera Gel Aloe Barbadensis (Aloe) Leaf Juice Aloe Vera Juice Aloe Barbadensis (Aloe) Leaf Juice Alum Amyris balsamifera (Amyris) Oil Amyris Essential Oil Amyris balsamifera (Amyris) Oil Anise Essential Oil Pimpinella Anisum (Anise) Oil Anise Powder Pimpinella Anisum (Anise Annatto Annatto (Bixa Orelana) Annatto Powder Annatto (Bixa orelana) Apricot Kernel Oil Prunus Armeniaca (Apricot) Kernel Oil Apricot Seed Powder Prunus Armeniaca (Apricot) Seed Powder Arnica Arnica Montana (Arnica) Arrowroot Powder Maranta Arundinaceae (Arrowroot) Ascorbic Acid USP/Vitamin C Acorbic Acid Avocado Persea Gratissima (Avocado) Fruit Avocado Oil Persea Gratissima (Avocado) Oil Babassu Oil Orbignya Oleifera (Babassu) Seed Oil Baking Soda Sodium Bicarbonate Balsam Fir Essential Oil Abies Balsamea (Balsam Canda) Resin Balsam Peru/Peru Balsam Essential Oil Myroxylon Pereira (Balsam Peru) -

Socioeconomic and Ethnobotanical Importance of the Breadfruit Tree (Artocarpus Communis J. G & G. Forster) in Benin

European Scientific Journal August 2018 edition Vol.14, No.24 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 Socioeconomic and Ethnobotanical Importance of the Breadfruit Tree (Artocarpus Communis J. G & G. Forster) in Benin Asaël J. Dossa, Msc, PhD Student Juste M. Amanoudo, Msc, PhD Student Towanou Houetchegnon, PhD, Assistant professor Christine Ouinsavi, PhD, Full professor Laboratory of Studies and Forestry Research (LERF), Faculty of Agronomy, University of Parakou, Parakou, Bénin Doi: 10.19044/esj.2018.v14n24p447 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/esj.2018.v14n24p447 Abstract This study aims to evaluate ethnobotanical knowledge that populations hold and income from the exploitation of the breadfruit (Artocarpus communis) in southern Benin. The data collected by interview and focus group are related to the uses of Artocarpus communis, harvest methods and the habitat of specie. The results show that A. communis is used for: food, trade, artisanal, energetic, cultural and medicinal. Local populations know the species with unequal distribution among gender (Men ID = 0.75 and IE = 0.08) and Women (ID = 0.48 and IE = 0.06); and when it comes to age (Young ID = 0.56 and IE = 0.07; Adult ID = 0.606 and IE = 0.08; Old ID = 0.75 and IE = 0.1) suggesting that people make various uses of the species. The most used plant part was the fruit (VUT=11, 87). These organs (Fruits, Flowers, Leaf), are collected either by picking or collecting, (bark) by debarking and (root) by digging. 50.51% of people surveyed collected those organs on breadfruit trees present at homes, 14.65% on those present in fields, 11.62% in the dregs and 23.23% in fallow lands.