Artemisia Gentileschi (1593 - Circa 1655)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Does Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration Look Like? a Gripping New Show at Moma PS1 Presents Startling Answers

On View (https://news.artnet.com/exhibitions/on-view) What Does Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration Look Like? A Gripping New Show at MoMA PS1 Presents Startling Answers Many of the works in the show were made by inmates in US prisons. Taylor Dafoe (https://news.artnet.com/about/taylor-dafoe-731), October 27, 2020 Installation view of Jesse Krimes, Apokaluptein 16389067 (2010–2013) in the exhibition "Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration." Courtesy of MoMA PS1. Photo: Matthew Septimus. Though many of the artists in “Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration (https://bookshop.org/books/marking-time-art-in-the-age-of-mass-incarceration/9780674919228?aid=1934),” a new show open now at MoMA PS1, have been convicted of crimes, only in a few cases do we learn the details. “I don’t talk about guilt and innocence, nor do I talk about why people are in prison, unless that’s important for them in terms of how they understand their art-making,” says Nicole R. Fleetwood, who organized the exhibition of works made from within, or about, the US prison system. For her, the show is about carcerality as a systemic, not an individual, problem. “As an abolitionist, if you start playing into the logic of good/bad, innocent/guilty, you start to think about prisons as if they’re about individual decision-making, which is often how we talk about it in a broader normative public,” she says. “Prisons don’t exist because of individual decision-making. They exist as a punitive, harsh way of governing around structural inequality and systemic abuse.” Larry Cook, The Visiting Room #4 (2019). -

Bodies of Knowledge: the Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Geoffrey Shamos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Shamos, Geoffrey, "Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1128. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Abstract During the second half of the sixteenth century, engraved series of allegorical subjects featuring personified figures flourished for several decades in the Low Countries before falling into disfavor. Designed by the Netherlandsâ?? leading artists and cut by professional engravers, such series were collected primarily by the urban intelligentsia, who appreciated the use of personification for the representation of immaterial concepts and for the transmission of knowledge, both in prints and in public spectacles. The pairing of embodied forms and serial format was particularly well suited to the portrayal of abstract themes with multiple components, such as the Four Elements, Four Seasons, Seven Planets, Five Senses, or Seven Virtues and Seven Vices. While many of the themes had existed prior to their adoption in Netherlandish graphics, their pictorial rendering had rarely been so pervasive or systematic. -

Experts Have Discovered a Previously Unknown Painting by Baroque Master Artemisia Gentileschi—And Now It’S up for Sale

AiA Art News-service Experts Have Discovered a Previously Unknown Painting by Baroque Master Artemisia Gentileschi—And Now It’s Up for Sale With its new attribution, the painting could fetch more than 10 times what it sold for just five years ago. Sarah Cascone, January 30, 2019 Artemisia Gentileschi, Saint Sebastian Tended by Irene . Estimate $400,000– 600,000. Courtesy of Sotheby's New York. There’s a new addition to the list of known works by famed Baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1654), and it’s coming up for auction tonight at Sotheby’s New York. The dramatically lit canvas, Saint Sebastian Tended by Irene, undeniably bears the hallmarks of the Old Master’s work, with its Caravaggesque lighting and focus on female agency, the wounded saint overshadowed by the two women ministering to his wounds. The auction house is expecting the painting to sell for $400,000–600,000, potentially an order of magnitude higher than when it last sold, at Bonhams London, for £40,000 ($62,804) on December 3, 2014. At the time, it was attributed to a “Follower of Caravaggio,” but the anonymous buyer already had a suspicion that the painting’s true authorship was far more interesting, as the potential handiwork of Gentileschi. Edoardo Roberti, a senior specialist in the Old Master paintings department at Sotheby’s, had the same hunch, and turned to experts to confirm the attribution. Nicola Spinosa, the former head of the Capodimonte Museum in Naples, and Giuseppe Porzio, an art history professor at the University of Naples, both examined the work and independently confirmed it was indeed by Gentileschi’s hand, likely made after she moved to Naples in 1630. -

Richard E. Spear Reviewed Work(S): Artemisia Gentileschi: Ten Years of Fact and Fiction Source: the Art Bulletin, Vol

Review: [untitled] Author(s): Richard E. Spear Reviewed work(s): Artemisia Gentileschi: Ten Years of Fact and Fiction Source: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 82, No. 3 (Sep., 2000), pp. 568-579 Published by: College Art Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3051402 Accessed: 13/10/2009 20:36 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. College Art Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Art Bulletin. http://www.jstor.org Book Reviews ARTEMISIA -

Download Issue (PDF)

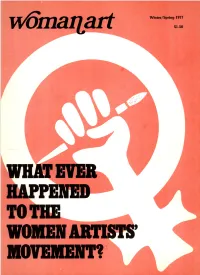

Vol. 1 No. 3 r r l S J L f J C L f f C t J I Winter/Spring 1977 AT LONG LAST —An historical view of art made by women by Miriam Schapiro page 4 DIALOGUES WITH NANCY SPERO by Carol De Pasquale page 8 THE SISTER CHAPEL —A traveling homage to heroines by Gloria Feman Orenstein page 12 'Women Artists: 1550— 1950’ ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI — Her life in art, part II by Barbara Cavaliere page 22 THE WOMEN ARTISTS’ MOVEMENT —An Assessment Interviews with June Blum, Mary Ann Gillies, Lucy Lippard, Pat Mainardi, Linda Nochlin, Ce Roser, Miriam Schapiro, Jackie Skiles, Nancy Spero, and Michelle Stuart page 26 THE VIEW FROM SONOMA by Lawrence Alloway page 40 The Sister Chapel GALLERY REVIEWS page 41 REPORTS ‘Realists Choose Realists’ and the Douglass College Library Program page 51 WOMANART MAGAZINE is published quarterly by Womanart Enterprises, 161 Prospect Park West, Brooklyn, New York 11215. Editorial submissions and all inquiries should be sent to: P. O. Box 3358, Grand Central Station, New York, N.Y. 10017. Subscription rate: $5.00 for one year. All opinions expressed are those o f the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those o f the editors. This publication is on file with the International Women’s History Archive, Special Collections Library, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60201. Permission to reprint must be secured in writing from the publishers. Copyright © Artemisia Gentileschi- Fame' Womanart Enterprises, 1977. A ll rights reserved. AT LONG LAST AN HISTORICAL VIEW OF ART MADE BY WOMEN by Miriam Schapiro Giovanna Garzoni, Still Life with Birds and Fruit, ca. -

Guercino: Mind to Paper/Julian Brooks with the Assistance of Nathaniel E

GUERCINO MIND TO PAPER GUERCINO MIND TO PAPER Julian Brooks with the assistance of Nathaniel E. Silver The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Front and back covers: Guercino. Details from The Assassination © 2006 J. Paul Getty Trust ofAmnon (cat. no. 14), 1628. London, Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery This catalogue was published to accompany the exhibition Guercino:Mind to Paper, held at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, October 17,2006, to January 21,2007, and at the Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery, London, February 22 Frontispiece: Guercino. Detail from Study of a Seated Young Man to May 13,2007. (cat. no. 2), ca. 1619. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum Pages 18—ic>: Guercino. Detail from Landscape with a View of a Getty Publications Fortified Port (cat. no. 22), ca. 1635. Los Angeles, J. Paul 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Getty Museum Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief Patrick E. Pardo, Project Editor Tobi Levenberg Kaplan, Copy Editor Catherine Lorenz, Designer Suzanne Watson, Production Coordinator Typesetting by Diane Franco Printed by The Studley Press, Dalton, Massachusetts All works are reproduced (and photographs provided) courtesy of the owners, unless otherwise indicated. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Brooks, Julian, 1969- Guercino: mind to paper/Julian Brooks with the assistance of Nathaniel E. Silver, p. cm. "This catalogue was published to accompany the exhibition 'Guercino: mind to paper' held at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, October 17,2006, to January 21,2007." Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-89236-862-4 (pbk.) ISBN-io: 0-89236-862-4 (pbk.) i. -

Dutch and Flemish Art at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts A

DUTCH AND FLEMISH ART AT THE UTAH MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS A Guide to the Collection by Ursula M. Brinkmann Pimentel Copyright © Ursula Marie Brinkmann Pimentel 1993 All Rights Reserved Published by the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112. This publication is made possible, in part, by a grant from the Salt Lake County Commission. Accredited by the CONTENTS Page Acknowledgments…………………………………………………………………………………………………..……...7 History of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts and its Dutch and Flemish Collection…………………………….…..……….8 Art of the Netherlands: Visual Images as Cultural Reflections…………………………………………………….....…17 Catalogue……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…31 Explanation of Cataloguing Practices………………………………………………………………………………….…32 1 Unknown Artist (Flemish?), Bust Portrait of a Bearded Man…………………………………………………..34 2 Ambrosius Benson, Elegant Couples Dancing in a Landscape…………………………………………………38 3 Unknown Artist (Dutch?), Visiones Apocalypticae……………………………………………………………...42 4 Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Charity (Charitas) (1559), after a drawing; Plate no. 3 of The Seven Virtues, published by Hieronymous Cock……………………………………………………………45 5 Jan (or Johan) Wierix, Pieter Coecke van Aelst holding a Palette and Brushes, no. 16 from the Cock-Lampsonius Set, first edition (1572)…………………………………………………..…48 6 Jan (or Johan) Wierix, Jan van Amstel (Jan de Hollander), no. 11 from the Cock-Lampsonius Set, first edition (1572)………………………………………………………….……….51 7 Jan van der Straet, called Stradanus, Title Page from Equile. Ioannis Austriaci -

Hendrick De Somer in Naples (1622-1654)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Netherlandish immigrant painters in Naples (1575-1654): Aert Mytens, Louis Finson, Abraham Vinck, Hendrick De Somer and Matthias Stom Osnabrugge, M.G.C. Publication date 2015 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Osnabrugge, M. G. C. (2015). Netherlandish immigrant painters in Naples (1575-1654): Aert Mytens, Louis Finson, Abraham Vinck, Hendrick De Somer and Matthias Stom. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:24 Sep 2021 CHAPTER THREE FIAMMINGO BY BIRTH, NEAPOLITAN BY ADOPTION: HENDRICK DE SOMER IN NAPLES (1622-1654) Between Finson’s departure in 1612 and De Somer’s arrival in 1622, the social and artistic conditions that Netherlandish painters faced in Naples changed decisively. -

Plotted, Shot, and Painted Cultural Representations of Biblical Women

JOURNAL FOR THE STUDY OF THE OLD TESTAMENT SUPPLEMENT SERIES 215 Editors David J.A. Clines Philip R. Davies Executive Editor John Jarick GENDER, CULTURE, THEORY 3 Editor J. Cheryl Exum Sheffield Academic Press This page intentionally left blank Plotted, Shot, and Painted Cultural Representations of Biblical Women J. Cheryl Exum Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 215 Gender, Culture, Theory 3 for my mother Rebecca Cockrell Exum and my other mothers Lucy Cockrell, in memoriam and Margaret L. Hines Copyright © 1996 Sheffield Academic Press Published by Sheffield Academic Press Ltd Mansion House 19 Kingfield Road Sheffield SI 1 9AS England Printed on acid-free paper in Great Britain by Bookcraft Ltd Midsomer Norton, Bath British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 1-85075-592-2 ISBN 1 85075-778-X pbk CONTENTS Preface 7 List of Figures 17 Chapter 1 BATHSHEBA PLOTTED, SHOT, AND PAINTED 19 Chapter 2 MICHAL AT THE WINDOW, MlCHAL IN THE MOVIES 54 Chapter 3 THE HAND THAT ROCKS THE CRADLE 80 Chapter 4 PROPHETIC PORNOGRAPHY 101 Chapter 5 is THIS NAOMI? 129 Chapter 6 WHY, WHY, WHY, DELILAH?+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 175 Bibliography 238 Index of References 253 Index of Authors 257 This page intentionally left blank PREFACE I had originally intended to call this book Still Amid the Alien Corn? In fact, it was previously announced by the publisher under that title, with Feminist and Cultural Studies in the Biblical Field as its subtitle. I liked having a question as a title, and I liked the cultural connections Still Amid the Alien Corn? established between the biblical book of Ruth, Keats's poem, Calderon's painting that appears on the cover, and the question my title implied; namely, whether or not, or to what extent, feminist criticism in the field of biblical studies is still, like Keats's Ruth amid the alien corn,1 considered marginal, an outsider taking up lodging within the discipline. -

Oh, Susanna: Exploring Artemisia’S Most Painted Heroine

Oh, Susanna: Exploring Artemisia’s Most Painted Heroine Kerry S. Kilburn ARTH 318 Dr. Anne H. Muraoka ARTH 318 S15 Susanna and the Elders 2 Dr. Anne Muraoka Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1656?)i was unique among Baroque artists. Not only was she a woman, she was a woman who eschewed still lifes and whose work extended beyond small devotional paintings to include the large history paintings considered the height of artistic – and until then, exclusively male - achievement. Among her many trademarks, Artemisia was known for creating series of paintings representing variations on a single theme.ii She painted four “Judith and her Maidservants,” for example, five or six “Penitent Magdalens,” and six “Bathshebas.”iii Although she prided herself on the originality of each painting, writing to Don Antonio Ruffo that “ . never has anyone found in my pictures any repetition of invention, not even of one hand,”iv each of these series includes at least one repeated image type (Fig. 1). She also painted a series of eight “Susanna and the Elders,” of which five are currently known (Fig. 2). Compared to the other series, this one is unique: it contains the largest number of paintings executed over the longest period of time with no repetition of image types. Although unique, this series of paintings can be understood in terms of several signature features of Artemisia’s style and oeuvre: growth and change in her artistic style over time; her practice of portraying heroic female protagonists; her specialty of painting erotic female nudes; and her narrative originality. Susanna’s story is told in the Book of Daniel (13:1-64). -

1- Collecting Seventeenth-Century Dutch Painting in England 1689

-1- COLLECTING SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY DUTCH PAINTING IN ENGLAND 1689 - 1760 ANNE MEADOWS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy t University College London, November, 1988. -2- ABSTIACT This thesis examines the collecting of seventeenth century Dutch painting in England from 1689 marking the beginning of auction sales in England to 1760, Just prior to the beginning of the Royal Academy and the rising patronage for British art. An examination of the composition of English collections centred around the period 1694 when William end Mary passed a law permitting paintings to be imported for public sale for the first time in the history of collecting. Before this date paintings were only permitted entry into English ports for private use and enjoyment. The analysis of sales catalogues examined the periods before and after the 1694 change in the law to determine how political circumstances such as Continental wars and changes in fiscal policy affected the composition of collecting paintings with particular reference to the propensity for acquiring seventeenth century Dutch painting in England Chapter Two examines the notion that paintings were Imported for public sale before 1694, and argues that there had been essentially no change In the law. It considered also Charles It's seizure of the City's Charters relaxing laws protecting freemen of the Guilds from outside competition, and the growth of entrepreneur- auctioneers against the declining power of the Outroper, the official auctioneer elected by the Corporation of City of London. An investigation into the Poll Tax concluded that the boom in auction sales was part of the highly speculative activity which attended Parliament's need to borrow public funds to continue the war with France. -

The University of Chicago “What Was She Wearing

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO “WHAT WAS SHE WEARING?”: LOOKING AT SUSANNA IN GOLDEN AGE SPAIN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ROMANCE LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES BY KATRINA JUNE POWERS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2017 Copyright 2017 by Katrina J. Powers ii In memory of Erik Toews iii Table of Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... viii Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................x Introduction ....................................................................................................................................1 I. The biblical tale and its critics ..........................................................................................3 II. Susanna and rape culture ................................................................................................16 III. Structure and methodology ............................................................................................30 Chapter I: “Ora en el vano yace en gran delectacion”: Susanna in Two Sixteenth-Century Plays ..............................................................................................................................................34