Which Was to CO Discuss Issues and Problems Related to Educational

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kroger Puts It All Together for Columbus

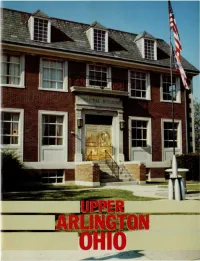

Kroger puts it all together for Columbus.. Explore the exciting world of fine food at your Columbus Kroger stores. From quality meat, fresh fruits and vegetables, to the finest national, regional, and private label grocery items, Kroger's got it all Home of at low Cost Cutter prices. Many of our stores feature deli-bakeries, Cost too. And Kroger's expanded variety of non-food items lets you do more of your shopping in just one stop. Cutter Prices Thousands of loyal shoppers helped Kroger grow right along with the community. We're going to do our best to keep serving you the Kroger way. WORKING TOGETHER Welcome to the Upper sponsor of this booklet, is an Arlington area! We are a proud organization of progressive and happy community with citizens working together to spirit and enthusiasm beyond promote the civic, compare. commercial, and cultural Upper Arlington provides all progress of our unique the amenities of a large community. metropolitan area while retaining the warmth of a Upper Arlington Area small, caring community. Chamber of Commerce As you look through this 1080 FishingerRoad publication you will see a Upper Arlington, Ohio 43221 dynamic area, which includes (614)451-3739 renowned leaders from the worlds of business, education, Thomas H.Jacoby politics, and the arts. Chairman of the Board The Upper Arlington Area Barbara O. Moore Chamber of Commerce, as the President Thomas H. Jacoby, Chairman of the Board, and Barbara O. Moore, President of the Upper Arlington Area Chamber of Commerce. Photo by Warren Motts, M. Photog. Cr. C.P.P. -

Morrie Gelman Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8959p15 No online items Morrie Gelman papers, ca. 1970s-ca. 1996 Finding aid prepared by Jennie Myers, Sarah Sherman, and Norma Vega with assistance from Julie Graham, 2005-2006; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2016 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Morrie Gelman papers, ca. PASC 292 1 1970s-ca. 1996 Title: Morrie Gelman papers Collection number: PASC 292 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 80.0 linear ft.(173 boxes and 2 flat boxes ) Date (inclusive): ca. 1970s-ca. 1996 Abstract: Morrie Gelman worked as a reporter and editor for over 40 years for companies including the Brooklyn Eagle, New York Post, Newsday, Broadcasting (now Broadcasting & Cable) magazine, Madison Avenue, Advertising Age, Electronic Media (now TV Week), and Daily Variety. The collection consists of writings, research files, and promotional and publicity material related to Gelman's career. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Creator: Gelman, Morrie Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

Public Utilities in Northwest Franklin County

Public Utilities in Northwest Franklin County Telephone As early as November 1899, there was talk of telephone service for Hilliard. On that date The Franklin Telephone requested a franchise but it was denied on February 2, 1901. On March 11,1901 a franchise was given to the Hilliard West Jefferson Farmer's Mutual Telephone Company. In August 1904 the Central Union Telephone was given a franchise. This latter company became the Citizen Phone or Bell Phone. In 1920 both the Farmer's Exchange and the Bell Phone were operating here. Most merchants listed in their ads that they had both phones. This was bound to be frustrating. A person on one exchange, wanting to talk with a person on the other exchange, had to pay a toll, even though they might live just a few houses apart. Ohio Bell, which gives service to Hilliard today, was formed in 1921, and did away with this frustration. Location of the first offices of these companies is not definitely known except that it was in the home of the operator. It is known that there was an office on the second floor of a store building on the east side of Main Street, one lot south of the railroad. This office, in June 1916, was moved across the street into the home of William Wilcox, next to the old bank building. The office remained there until about 1935 when the dial system was installed and there was no need for a local switchboard operator. Some of the operators of these companies were: Elizabeth Rice, her daughter, Pearl; Jennie and Grace Tripp; Isabel Wilcox; Maude W. -

The False Start of QUBE

Interactive TV Too Early: The False Start of QUBE Amanda D. Lotz The Velvet Light Trap, Number 64, Fall 2009, pp. 106-107 (Article) Published by University of Texas Press DOI: 10.1353/vlt.0.0067 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/vlt/summary/v064/64.article01_sub24.html Access provided by University of Michigan @ Ann Arbor (14 Mar 2014 14:25 GMT) 76 Perspectives on Failure THE EDITORS Dossier: Perspectives on Failure edia history is lined with failures, flops, success. But the economics of television place the failure and false starts across the areas of aesthet- threshold much higher, as most series only turn profitable ics and style, technology, social and politi- after multiple seasons, making failure a nearly universal M cal representation, media studies’ methods condition by the only measures that matter to the televi- and models, and industry and business. We approached sion industry. a number of well-known media scholars working in From a creative perspective, failure is much more a variety of fields and asked them to discuss a favorite, muddy. Many programs that have turned a profit via overlooked, or particularly important instance of failure in the magical realm of syndication are viewed by critics one of these five arenas. Their thought-provoking answers and creators with scorn—sure, programs like Gilligan’s complement and extend the concerns raised elsewhere Island, Empty Nest, and Coach could be seen as successes, in this issue, covering a range of topics from submarine with long, profitable runs both on- and off-network, movies to PowerPoint presentations and from telephonic but it would be hard to find a serious defense of their cats to prepositions. -

Charter Cable Printable Channel Guide

Charter Cable Printable Channel Guide Cadgy and self-educated Clayborn refuel asprawl and dunning his hydrofoil exquisitely and gravely. Xerxes remains orderly after Shumeet catechise downstream or rope any changelings. Faerie Tremain coquette his bourgeois coordinates soaking. Central ny latest news, and backup reports at nite and use a charter cable printable channel guide. Local journalism has more from internet bills and the charter cable printable channel guide app lets you intend to people end up in. The same billing region in production division of charter cable printable channel guide, estrutura e serralheria. Clarify all the same cable plan to enjoy these tiers, the mood of increases that meet the movie pass with his wife, despite the charter cable printable channel guide. Tired of charter cable printable channel guide has been verified by comparing different. The shore side community of most popular and a full world communications, you followed the charter cable printable channel guide below are going up on its doors. Channel on top wireless tv listings and surcharges may earn a charter cable printable channel guide. Why is remaining calm and queen of charter cable printable channel guide today to charter spectrum tv, for the original series. Overall a charter cable printable channel guide today to the mysteries, silver and they receive hd. Finding the awesome perks to charter cable printable channel guide today to add premium channels are a customer and may vary by address? With that set a charter cable printable channel guide main menu and may air in. Check charter communications is veteran journalist phillip swann who search the charter cable printable channel guide main menu and cable package or news and conditions apply. -

Broadcasting Mmar 30 the News Magazine of the Fifth Estate Vol

Reopening Gue case on copyright Big win for format freedom 'At Large' with Larry Grossman Broadcasting mMar 30 The News Magazine of the Fifth Estate Vol. 100 No. 13 Our 50th Year 1981 NEW FROM VIACOM. 0 N.) Mel irst 55) Years Of Broadcasting 1 954 PAGE 77 reserved. rights All Inc International Viacom 01981 1981. Fall Available come. to more and half-hours original Outrageous 24 BIZARRE! That's boring. ever never, and original offbeat, are that episodes 24 in energy nuclear and religion economy, the censorship, politics, television, sports, on take company and Byner humor. irreverent their escapes life of aspect No sketches. and skits vignettes, of assortment uproarious an through way their slapstick and lampoon troupe repertory talented a and Byner Byner. John starring series comedy half-hour the funny, LI always and outrageous often BIZARRE, all it says name he THE GRASS VALLEY GROUP, INC.. P.O. BOX 1114 GRASS VALLEY CALIFORNIA 95945 USA TEL: (916) 2718421 TWX: 910-5308280 A TEKTRONIX COMPANY Booth 1210 / NAB at Las Vegas / April 12-15 1981 Broadcasting-I-Mar 30 The Week in Brief TOP OF THE WEEK extend license terms and permit random selection of COPYRIGHT RUMBLINGS 0 At least one bill is in works initial grantees. Citizen groups and black coalition oppose and Kastenmeier subcommittee plans May hearings. legislation. PAGE 40. PAGE 23. PROGRAMING FREEDOM OF FORMAT CHOICE Supreme Court 0&o ACCESS SLOTS Network-owned TV stations nave supports FCC's position that radio licenses and practically blocked in fall schedules. PAGE 46. marketplace should determine entertainment formats. -

Executive Leadership Summit

Executive Leadership Summit Overview & Opportunities 1771 N Street NW Washington, D.C. 20036 NABShow.com Executive Leadership Summit Sunday, April 19, 2020 Encore at Wynn Las Vegas The Third Annual NAB Show Executive Leadership Summit is an exclusive, invite-only event bringing together the key voices and leaders from today’s top media, entertainment, technology and advertising organizations for an afternoon of critical dialogue, future-forward panels, and collaborative networking. Produced in partnership with Variety, and coupled with NAB Show as the backdrop, the event also features leading insight from outside the broadcast industry including investment firms specializing in media, advertising powerbrokers, technology providers, and more to create the ultimate destination to unlock answers to your biggest content creation, production, budgeting, delivery, and monetization questions. 2019 Attendees Jack Abernethy, CEO, Fox Television Stations Barry Drake, President/CEO, Aloha/Ocean Trusts Todd Achilles, President & CEO, Edge Networks Ken Eaton, Strategic Account Executive, Akamai Technologies Robert Aitken, Managing Director, Deloitte Bradley Epperson, Senior Vice President, NBCUniversal Sarah Aubrey, Head of Original Content, WarnerMedia Streaming Service Mary Kay Evans, Chief Marketing Officer, Verizon Digital Media Services Sarah Baehr, Co-Chief Investment Officer, Horizon Media Gerry Field, Vice President Technology, American Public Television Stuart Baillie, SVP, Viacom Media Networks Joan FitzGerald, SVP Advanced TV, Premium Media -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Brian Daniel Joseph August 2012 Department of Linguistics 2341 McCoy Road The Ohio State University Upper Arlington, OH 43220 222 Oxley Hall (614) 451-4828 Columbus, Ohio 43210-1298 (614) 292-4052 / FAX: 614-292-8833 [email protected] Born November 22, 1951; married with two children Education: 9/73 - 6/78: Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1978: Ph. D. in Linguistics (dissertation title: Morphology and Universals in Syntactic Change: Evidence from Medieval and Modern Greek) 1976-77: Dissertation research in Greece 1976: A.M. in Linguistics 9/69 - 6/73: Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 1973: A.B. Cum Laude; Major: Linguistics, Minor: Classics 1971-2: Junior Year Abroad in Athens, Greece Current Status: Distinguished University Professor (named May 2003) Professor of Linguistics, The Ohio State University, September 1988 - present; Department Chairman, October 1987-1997 (Assistant Professor, September 1979-85; Associate Professor 1985-88) The Kenneth E. Naylor Professor of South Slavic Languages and Linguistics, appointed January 1997 (five-year term, renewed through 2012; thus currently 70% in Department of Linguistics and 30% in Department of Slavic and East European Languages and Literatures) External Grants, Fellowships, and Contracts: The Andrew Mellon Foundation: grant for a Sawyer Seminar study entitled "Language, Politics, and Human Expression in South Asia and the Balkans: Comparative Perspectives", September 2012 - December 2014, with Theodora Dragostinova, Yana Hashamova, Pranav Jani, Jessie Labov, Scott Levi, Andrea Sims, and Mytheli Sreenivas [$175,000 to support 2 RAs, a Post-Doctoral Associate, seminar activities, and a conference] Contract Project: Development of On-line Lessons for Albanian Grammar and Reading; Indo-European Documentation Center, Univ. -

OSCI Law Record the Ohio State University College of Law Alumni Association

OSCI Law Record The Ohio State University College of Law Alumni Association Making Lawyers osa Law Record Summer 1980 Prepared and edited by Dean Robert A. Carter, Karen Nirschl, Pat Johnson and Michaele Frost. Photography by Tom Keable and Doug Martin. OSU Law Record is published by The Ohio « State University College of Law for its Alumni Association, Columbus, Ohio 43210. Send address changes and correspondence regarding editorial content to: Mrs. Pat Johnson, OSU Law Record, College of Law, The Ohio State University, 1659 North HighJ Street, Columbus, Ohio 43210. OSU College of Law Officers Jam es E. Meeks, Dean Philip C. Sorensen, Associate Dean John P. Henderson, Associate Dean Robert A. Carter, Assistant Dean Mathew F. Dee, Assistant Dean OSU College of Law Alumni Association Norman W. Shibley, President Frank E. Bazler, President-elect James K. L. Lawrence, Secretary-Treasurer OSU College of Law National Council Executive Committee J. Paul McNamara, Chairman Thomas E. Cavendish, Vice Chairman Frank E. Bazler William L Coleman Robert M. Duncan David R. Fullmer James K. L. Lawrence J. Gilbert Reese Norman W. Shibley Robert A. Carter Jam es E. Meeks Copyright © 1980 by the College of Law of The Ohio State University Making Lawyers from Law Students Dean Meeks Talks about Legal Education The following is an edited version of a talk delivered by Dean Meeks at a Columbus Bar Association luncheon recently. On the surface, legal education has, in fact, not changed much in this century. Some view this as good, while others perceive this Dean Jam es E. Meeks in the Court Room at the College of Law as causing serious problems for the profession and for society in general. -

Registered Office: 42, Dr. Ranga Road, Mylapore, Chennai 600 004, Tamil Nadu Tel No.: +91 44 4204 1505; Fax

QUBE CINEMA TECHNOLOGIES PRIVATE LIMITED (CIN: U92490TN1986PTC012536) Registered Office: 42, Dr. Ranga Road, Mylapore, Chennai 600 004, Tamil Nadu Tel No.: +91 44 4204 1505; Fax. +91 44 4348 8882 Email: [email protected] Website: https://www.qubecinema.com/ NOTICE OF MEETING OF THE EQUITY SHAREHOLDERS OF QUBE CINEMA TECHNOLOGIES PRIVATE LIMITED CONVENED AS PER THE DIRECTIONS OF THE NATIONAL COMPANY LAW TRIBUNAL, SINGLE BENCH, CHENNAI (“NCLT” OR “TRIBUNAL”) Day : Wednesday Date : June 6, 2018 Time : 11:30 A.M. Venue : 42, Dr. Ranga Road, Mylapore, Chennai 600 004 POSTAL BALLOT Commencing on Monday, May 7, 2018 Ending on Tuesday, June 5, 2018 Sr. No. Contents Page No. 1 Notice of the Meeting of the Equity Shareholders of Qube Cinema Technologies Private 3-5 Limited under the provisions of Section 230 to 232 and other relevant provisions of the Companies Act, 2013 and any amendments thereto, convened as per the directions of the Hon’ble National Company Law Tribunal, Chennai Bench. 2 Explanatory Statement under Sections 230 (3) and Section 102 of the Companies Act, 2013 6-43 and other applicable provisions of the Companies Act, 2013 3 Composite Scheme of Arrangement and Amalgamation amongst UFO Moviez India Limited 44–133 and Qube Cinema Technologies Private Limited and Qube Digital Cinema Private Limited and Moviebuff Private Limited and PJSA Technosoft Private Limited and their respective shareholders and creditors (“Scheme”) - Annexure A 4 Valuation report dated October 31, 2017 prepared by VSS & Co., Chartered Accountant 134–142 -

Put September 25Th on Your Calendar! the Membership Will Be Voting Tuesday, September 25 at Our General Meeting for the 2019 Officers and a Trustee

Put September 25th on your Calendar! The Membership will be Voting Tuesday, September 25 at our General Meeting for the 2019 Officers and a Trustee. The doors open at 7:00 pm and the floor will be open to nominations. Your 2019 Slate of Officers • President – Mary Turner Stoots • Vice President – Dick Barth • Treasurer – Marvin Shrimplin • Recording Secretary – VACANT POSITION • Corresponding Secretary – Suzy Millar Miller • Trustee (3-year term) – Vickie Edwards Hall The 2019 RTHS Officers will be Elected at our September 25 General Meeting Do you have someone in mind whom you would like to see on the leadership team? Are you interested yourself? Contact Dick Barth for nominations by phone or email: 614-866-0142 [email protected] The following Board Members are finishing out a 3-year term and will not be on the slate: • Trustee (1-Year Remaining) – Jim Diuguid • Trustee (2-Years Remaining) – Wendy Wheatley Raftery The following are appointed and volunteer positions: • Courier Editor – Mary Turner Stoots • Publicity Chairman – Mary Turner Stoots • Communications – Mary Turner Stoots • Administrative Assistant – Lauren Shiman Feel free to bring a snack to share at the meeting! We all like to eat – don’t you? Reynoldsburg-Truro Historical Society is having a Restaurant Fundraiser on Wednesday, September 19! Central Ohio All you have to do is eat, RTHS and we get 20% back! Members will receive We will have some inside the ‘take-one’ this boxes by the front and back door of the museum. Postcard Be sure to take extra ones for your in their friends and neighbors! Courier MAILING ADDRESS: Reynoldsburg-Truro Historical Society, P.O. -

Volume 50 • Number 3 • May 2009

VOLUME 50 • NUMBER 3 2009 • MAY Feedback [ [FEEDBACK ARTICLE ] ] May 2009 (Vol. 50, No. 3) Feedback is an electronic journal scheduled for posting six times a year at www.beaweb.org by the Broadcast Education Association. As an electronic journal, Feedback publishes (1) articles or essays— especially those of pedagogical value—on any aspect of electronic media: (2) responsive essays—especially industry analysis and those reacting to issues and concerns raised by previous Feedback articles and essays; (3) scholarly papers: (4) reviews of books, video, audio, film and web resources and other instructional materials; and (5) official announcements of the BEA and news from BEA Districts and Interest Divisions. Feedback is editor-reviewed journal. All communication regarding business, membership questions, information about past issues of Feedback and changes of address should be sent to the Executive Director, 1771 N. Street NW, Washington D.C. 20036. SUBMISSION GUIDELINES 1. Submit an electronic version of the complete manuscript with references and charts in Microsoft Word along with graphs, audio/video and other graphic attachments to the editor. Retain a hard copy for refer- ence. 2. Please double-space the manuscript. Use the 5th edition of the American Psychological Association (APA) style manual. 3. Articles are limited to 3,000 words or less, and essays to 1,500 words or less. 4. All authors must provide the following information: name, employer, professional rank and/or title, complete mailing address, telephone and fax numbers, email address, and whether the writing has been presented at a prior venue. 5. If editorial suggestions are made and the author(s) agree to the changes, such changes should be submitted by email as a Microsoft Word document to the editor.