8.1.3. Historical Background August 2014 Somme Tour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROCES VERBAL DU CONSEIL COMMUNAUTAIRE Mercredi 20 Mai 2020

PROCES VERBAL DU CONSEIL COMMUNAUTAIRE Mercredi 20 mai 2020 L’an deux mille vingt, le mercredi vingt mai, à dix-huit heures, le Conseil Communautaire, légalement convoqué, s’est réuni au nombre prescrit par la Loi, en visioconférence. Ont assisté à la visioconférence : Aizecourt le Bas : Mme Florence CHOQUET - Allaines : M. Bernard BOURGUIGNON - Barleux : M. Éric FRANÇOIS – Brie : M. Marc SAINTOT - Bussu : M. Géry COMPERE - Cartigny : M. Patrick DEVAUX - Devise : Mme Florence BRUNEL - Doingt Flamicourt : M. Francis LELIEUR - Epehy : Mme Marie Claude FOURNET, M. Jean-Michel MARTIN- Equancourt : M. Christophe DECOMBLE - Estrées Mons : Mme Corinne GRU – Eterpigny : : M. Nicolas PROUSEL - Etricourt Manancourt : M. Jean- Pierre COQUETTE - Fins : Mme Chantal DAZIN - Ginchy : M. Dominique CAMUS – Gueudecourt : M. Daniel DELATTRE - Guyencourt-Saulcourt : M. Jean-Marie BLONDELLE- Hancourt : M. Philippe WAREE - Herbécourt : M. Jacques VANOYE - Hervilly Montigny : M. Richard JACQUET - Heudicourt : M. Serge DENGLEHEM - Lesboeufs : M. Etienne DUBRUQUE - Liéramont : Mme Véronique VUE - Longueval : M. Jany FOURNIER- Marquaix Hamelet : M. Bernard HAPPE – Maurepas Leforest : M. Bruno FOSSE - Mesnil Bruntel : M. Jean-Dominique PAYEN - Mesnil en Arrouaise : M. Alain BELLIER - Moislains : Mme Astrid DAUSSIN, M. Noël MAGNIER, M. Ludovic ODELOT - Péronne : Mme Thérèse DHEYGERS, Mme Christiane DOSSU, Mme Anne Marie HARLE, M. Olivier HENNEBOIS, , Mme Catherine HENRY, Mr Arnold LAIDAIN, M. Jean-Claude SELLIER, M. Philippe VARLET - Roisel : M. Michel THOMAS, M. Claude VASSEUR – Sailly Saillisel : Mme Bernadette LECLERE - Sorel le Grand : M. Jacques DECAUX - Templeux la Fosse : M. Benoit MASCRE - Tincourt Boucly : M Vincent MORGANT - Villers-Carbonnel : M. Jean-Marie DEFOSSEZ - Villers Faucon : Mme Séverine MORDACQ- Vraignes en Vermandois : Mme Maryse FAGOT. Etaient excusés : Biaches : M. -

CC De La Haute Somme (Combles - Péronne - Roisel) (Siren : 200037059)

Groupement Mise à jour le 01/07/2021 CC de la Haute Somme (Combles - Péronne - Roisel) (Siren : 200037059) FICHE SIGNALETIQUE BANATIC Données générales Nature juridique Communauté de communes (CC) Commune siège Péronne Arrondissement Péronne Département Somme Interdépartemental non Date de création Date de création 28/12/2012 Date d'effet 31/12/2012 Organe délibérant Mode de répartition des sièges Répartition de droit commun Nom du président M. Eric FRANCOIS Coordonnées du siège Complément d'adresse du siège 23 Avenue de l'Europe Numéro et libellé dans la voie Distribution spéciale Code postal - Ville 80200 PERONNE Téléphone Fax Courriel [email protected] Site internet www.coeurhautesomme.fr Profil financier Mode de financement Fiscalité professionnelle unique Bonification de la DGF non Dotation de solidarité communautaire (DSC) non Taxe d'enlèvement des ordures ménagères (TEOM) oui Autre taxe non Redevance d'enlèvement des ordures ménagères (REOM) non Autre redevance non Population Population totale regroupée 27 799 1/5 Groupement Mise à jour le 01/07/2021 Densité moyenne 59,63 Périmètre Nombre total de communes membres : 60 Dept Commune (N° SIREN) Population 80 Aizecourt-le-Bas (218000123) 55 80 Aizecourt-le-Haut (218000131) 69 80 Allaines (218000156) 460 80 Barleux (218000529) 238 80 Bernes (218000842) 354 80 Biaches (218000974) 391 80 Bouchavesnes-Bergen (218001097) 291 80 Bouvincourt-en-Vermandois (218001212) 151 80 Brie (218001345) 332 80 Buire-Courcelles (218001436) 234 80 Bussu (218001477) 220 80 Cartigny (218001709) 753 80 Cléry-sur-Somme -

ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Name (As On

Houses of Parliament War Memorials Royal Gallery, First World War ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Also in Also in Westmins Commons Name (as on memorial) Full Name MP/Peer/Son of... Constituency/Title Birth Death Rank Regiment/Squadron/Ship Place of Death ter Hall Chamber Sources Shelley Leopold Laurence House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Baron Abinger Shelley Leopold Laurence Scarlett Peer 5th Baron Abinger 01/04/1872 23/05/1917 Commander Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve London, UK X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Humphrey James Arden 5th Battalion, London Regiment (London Rifle House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Adderley Humphrey James Arden Adderley Son of Peer 3rd son of 2nd Baron Norton 16/10/1882 17/06/1917 Rifleman Brigade) Lincoln, UK MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) The House of Commons Book of Bodmin 1906, St Austell 1908-1915 / Eldest Remembrance 1914-1918 (1931); Thomas Charles Reginald Thomas Charles Reginald Agar- son of Thomas Charles Agar-Robartes, 6th House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Agar-Robartes Robartes MP / Son of Peer Viscount Clifden 22/05/1880 30/09/1915 Captain 1st Battalion, Coldstream Guards Lapugnoy, France X X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Horace Michael Hynman Only son of 1st Viscount Allenby of Meggido House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Allenby Horace Michael Hynman Allenby Son of Peer and of Felixstowe 11/01/1898 29/07/1917 Lieutenant 'T' Battery, Royal Horse Artillery Oosthoek, Belgium MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Aeroplane over House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Francis Earl Annesley Francis Annesley Peer 6th Earl Annesley 25/02/1884 05/11/1914 -

Notable Advance Made by British

1796 TWO CENTS VOL LVIII. NO. 224 POPULATION 28,219 NORWICH, CONN., SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 16, 1916 16 PAGES 128 COLUMNS PRICE The Bulletin's Circulation in Norwich is Double That of Any Other Paper, and Its Total Circulation is the Largest in Connecticut in Proportion to the City's Population Cabled Paragraphs (llSter Political $935,000 Bail for Cr; 'nsed Telegrams TAKING SYMPATHETIC STRIKE VOTE NOTABLE ADVANCE Grandson of Charles Dickens III Fire destroyed the Tournir hotel at ' London, Sept. 16, 2.22 a. m. Mp Babylon, N. Y. , Charles Dickens, grands'-Charle- s Dickens, was killed ir , Meeting Planned Industrial Workers The has transferred in France Monday. $1.:C,J;0 to New Orleans. If Strike is Authorized Union Leaders Believe It Belgian Steamer of pig in Germany FOR WIND-U- P OF CAMPAIGN BY Production iron MADE BY BRITISH London, Sept. 15, j. The WHO PARTICIPATED IN FORBID- in August was 1,145,000 tons. Hasten Settlement of New York Traction Strike Belgian en steamer Marc sunk, NOMINEE HUGHES DEN MEETING AT OLD FORGE, PA. according to an anno, jient made D. Caolamanos has been appointed tonight by Lloyds. Greek minister to the United States. New French War Loan Approved. IN MADISON SQ. GARDEN 267 ARRESTS WERE MADE Four suspected cases of infantile pa- VOTE OF MACHINISTS SAID TO FAVOR STRIKE Have Smashed the German Line On a Front of Five Paris, Sept. 15. 6.30 p. m. The ralysis are reported in the city of senate today by an unanimous vote Dublin. adopting the bill authorizing the new Miles North of the Somme war loan proposed by Finance Minis- Meeting is to be Held on Saturday, Each Defendant Was Fined $10 for Sir Sigmund Neumann, the South passed cham- ter Ribot. -

Beaumont-Hamel and the Battle of the Somme, Onwas Them, Trained a Few and Most Were Minutes Within Killed of the Assault

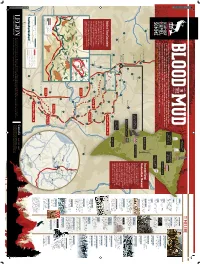

2015-12-18 2:03 PM Hunter’s CWGC TIMELINE Cemetery 1500s June 1916 English fishermen establish The regiment trains seasonal camps in Newfoundland in the rain and mud, waiting for the start of the Battle of the Somme 1610 The Newfoundland Company June 28, 1916 Hawthorn 51st (Highland) starts a proprietary colony at Cuper’s Cove near St. John’s The regiment is ordered A century ago, the Newfoundland Regiment suffered staggering losses at Beaumont-Hamel in France Ridge No. 2 Division under a mercantile charter to move to a forward CWGC Cemetery Monument granted by Queen Elizabeth I trench position, but later at the start of the Battle of the Somme on July 1, 1916. At the moment of their attack, the Newfoundlanders that day the order is postponed July 23-Aug. 7, 1916 were silhouetted on the horizon and the Germans could see them coming. Every German gun in the area 1795 Battle of Pozières Ridge was trained on them, and most were killed within a few minutes of the assault. German front line Newfoundland’s first military regiment is founded 9:15 p.m., June 30 September 1916 For more on the Newfoundland Regiment, Beaumont-Hamel and the Battle of the Somme, to 2 a.m., July 1, 1916 Canadian troops, moved from go to www.legionmagazine.com/BloodInTheMud. 1854 positions near Ypres, begin Newfoundland becomes a crown The regiment marches 12 kilo- arriving at the Somme battlefield Y Ravine CWGC colony of the British Empire metres to its designated trench, Cemetery dubbed St. John’s Road Sept. -

The Battle of the Somme

THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME FIRST PHASE BY JOHN BUCHAN THOMAS NELSON ft SONS, LTD., 35 & 36, PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON, E.C. EDINBURGH. NEW VORK. 4 PARIS. 1922 — THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME.* CHAPTER I. PRELIMINARIES. ROM Arras southward the Western battle- front leaves the coalpits and sour fields F of the Artois and enters the pleasant region of Picardy. The great crook of the upper Somme and the tributary vale of the Ancre intersect a rolling tableland, dotted with little towns and furrowed by a hundred shallop chalk streams. Nowhere does the land rise higher than 500 feet, but a trivial swell—such is the nature of the landscape jxfay carry the eye for thirty miles. There are few detached farms, for it is a country of peasant cultivators who cluster in villages. Not a hedge breaks the long roll of eomlands, and till the higher ground is reached the lines of tall poplars flanking the great Roman highroads are the chief landmarks. At the lift of country between Somme and Ancre copses patch tlje slopes, and the BATTLE OF THE SOMME. sometimes a church spire is seen above the trees winds iron) some woodland hamlet* The Somme faithfully in a broad valley between chalk bluffs, •dogged by a canal—a curious river which strains, “ like; the Oxus, through matted rushy isles,” and is sometimes a lake and sometimes an expanse of swamp, The Ancre is such a stream as may be found in Wiltshire, with good trout in, its pools. On a hot midsummer day the slopes are ablaze with yellow mustard, red poppies and blue cornflowers ; and to one coming from the lush flats of Flanders, or the “ black country ” of the Pas dc Calais, or the dreary levels of Champagne, or the strange melancholy Verdun hills, this land wears a habitable and cheerful air, as if remote from the oppression of war. -

Claremen Who Fought in the Battle of the Somme July-November 1916

ClaremenClaremen who who Fought Fought in The in Battle The of the Somme Battle of the Somme July-November 1916 By Ger Browne July-November 1916 1 Claremen who fought at The Somme in 1916 The Battle of the Somme started on July 1st 1916 and lasted until November 18th 1916. For many people, it was the battle that symbolised the horrors of warfare in World War One. The Battle Of the Somme was a series of 13 battles in 3 phases that raged from July to November. Claremen fought in all 13 Battles. Claremen fought in 28 of the 51 British and Commonwealth Divisions, and one of the French Divisions that fought at the Somme. The Irish Regiments that Claremen fought in at the Somme were The Royal Munster Fusiliers, The Royal Irish Regiment, The Royal Irish Fusiliers, The Royal Irish Rifles, The Connaught Rangers, The Leinster Regiment, The Royal Dublin Fusiliers and The Irish Guards. Claremen also fought at the Somme with the Australian Infantry, The New Zealand Infantry, The South African Infantry, The Grenadier Guards, The King’s (Liverpool Regiment), The Machine Gun Corps, The Royal Artillery, The Royal Army Medical Corps, The Royal Engineers, The Lancashire Fusiliers, The Bedfordshire Regiment, The London Regiment, The Manchester Regiment, The Cameronians, The Norfolk Regiment, The Gloucestershire Regiment, The Westminister Rifles Officer Training Corps, The South Lancashire Regiment, The Duke of Wellington's (West Riding Regiment). At least 77 Claremen were killed in action or died from wounds at the Somme in 1916. Hundred’s of Claremen fought in the Battle. -

Ernest James Thelwell

166: Ernest James Thelwell Basic Information [as recorded on local memorial or by CWGC] Name as recorded on local memorial or by CWGC: Ernest James Thelwell Rank: Private Battalion / Regiment: King’s Coy. 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards Service Number: 23178 Date of Death: 25 September 1916 Age at Death: 25 Buried / Commemorated at: Thiepval Memorial, Thiepval, Departement de la Somme, Picardie, France Additional information given by CWGC: Son of James and Catherine Thelwell, of 38, Overleigh Rd., Chester. Ernest James Thelwell was the eldest son of Police Constable James and Catherine Thelwell and he was born on 22 March 1892 when his parents were living in Eastham. James Thelwell (a son of agricultural labourer William and Sarah Thelwell) married Catherine Jones (a daughter of Thomas) at St Mary’s Church, Edge Hill, Liverpool in late 1889 and their first child, Dora Elizabeth, was born in late 1890 when James was a constable in Woodchurch. In the 1891 census the family was still recorded in Woodchurch: 1901 census (extract) – Upton Road, Woodchurch, Birkenhead James Thelwell 27 police constable born Malpas Catherine 27 born Denbigh Dora 6 months born Woodchurch By the time of the 1901 census the family had moved to Neston where James was a policeman. It appears that James left the police force in Birkenhead to join the constabulary in Eastham shortly after the 1891 census and he remained there until (probably) mid-1897. 1901 census (extract) – Parkgate Road, Neston James Thelwell 38 police constable born Malpas Catherine 38 born Denbigh Dora 10 born Chester Ernest 9 born Eastham William 7 born Eastham Ruth 6 born Eastham Gwenyth 5 born Eastham Charles 3 born Neston Henry 2 months born Neston Page | 1745 Although the census records that Dora Elizabeth was born in Chester it is known that she was born in Woodchurch. -

Famille BLÉRIOT & Familles SLOSSE, DEMESSINE & LUYSSAERT

Famille BLÉRIOT & familles SLOSSE, DEMESSINE & LUYSSAERT Branches de Cléry s/Somme, Cappelle-en-Pévèle & Lille à partir des Recherches d’ Alphonse Blériot continuées & enrichies par Fortuné Blériot encore complétées par des descendants contemporains, mes chers cousins & cousines (merci Luc !, merci Annette !, merci François !, merci Roselyne !) ainsi que par les publications de divers sites généalogiques (Généanet, etc.) & Etats militaires (Généanet, site Mémoire des Hommes) les Archives du Nord (état civil, états militaires) & Archives de la Somme (recensements entre 1836 & 1881, état civil 1793-1892) & archives du bailliage de Péronne (1745-1754) Voir aussi : Blériot_compléments : actes d’état civil, photos & divers documents © 1981, 2007 Etienne Pattou Dernière mise à jour : 20/09/2021 sur http://racineshistoire.free.fr/LGN 1 LOCALISATIONS (les n° de séquence renvoient à la carte) LOCALISATIONS par PATRONYMES (vers 1980) [ à rapprocher des localisations de la famille de Louis, l’aviateur, p. 25 ] GINCHY (80) GUILLEMONT (80) ETREAUPONT (02) 1) GINCHY (Somme (80) près Péronne et Combles) Aimé Châtelain Blériot 2) GUILLEMONT (Somme (80) près Péronne et Combles) Balluet Corion Leroy 3) ETREAUPONT (Aisne (02), près Vervins et La Capelle) Blériot Demarquay 4) NEUVILLE BOURJONVAL (Pas-de-Calais (62), près Arras et Bertincourt) Boulan Forget SORBAIS (02) 5) MORVAL (Pas-de-Calais (62), près Arras et Bapaume) Cartigny Guillemont Leroy 6) SORBAIS (Aisne (02), près Vervins et La Capelle) Châtelain Pinard Gosset 7) BEAUMONT (?)-HAMEL ((?) - nombreux -

Pembroke College, Cambridge the Dead of the War of 1914-1918 1. The

PEMBROKE COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE THE DEAD OF THE WAR OF 1914-1918 1. THE 1914-1918 WAR MEMORIAL At Pembroke College, Cambridge the memorial to those of the College identified as having died in the war of 1914-18 is next to the entrance to the college chapel, on the West side of the Hitcham cloister; and the memorial for the war of 1939-45 is opposite, on the East side of the same cloister. The former was designed by T.H. Lyon,[1] made by the Cambridge stonemasons and builders Messrs Rattee and Kett,[2] and dedicated by the then Bishop of Wakefield[3] on 3 December 1924, at a ceremony over which the then Master of Pembroke College[4]presided. The first memorial records three-hundred and eight names,[5] the second one hundred and fifty-two.[6] In each case only those dying on the Allied side are listed. Likewise, for the First war only those killed in action or dying of wounds or other illnesses contracted in military service up to the Armistice are shown.[7] Aside from the omission of those (relatively few) who may have died on the Austro-German and Ottoman side (of whom up to six may in due course be identifiable)[8] or of those whose death, although related to war service, occurred after the list had been drawn up for the stonemasons, the main source of uncertainty in the coverage of the 1914-18 listing concerns having or not belonged to Pembroke College. [9] From 1914 onwards this uncertainty also affects the year recorded as that of first belonging to the College. -

Voir Plan Détail 1 Commune De Ginchy : PLU Plan Global : Zones Avec Câbles Et/Ou Conduites "Orange" En Terrain Priv

GUEUDECOURT FLERS LE TRANSLOY LESBOEUFS M6A MORVAL MED L1NMED SAILLY-SAILLISEL LONGUEVAL GINCHY Voir plan détail 1 GUILLEMONT COMBLES COB CL MONTAUBAN-DE-PICARDIE Commune de Ginchy : PLUHARDECOURT-AUX-BOIS Plan global : zones avec câbles et/ou conduites "Orange" en terrain privé . MAUREPAS A10 zone avec câble "orange" pleine terre en terrain privé . Commune de Ginchy : PLU Plan de détail 1 ; zone avec câble en terrain privé. MAUREPAS Voir plan détail 2 CURLU CLERY-SUR-SOMME HEM-MONACU Voir plan détail 1 FRISE Commune de Hem Monacu :: PLU Plan global : Zones avec câbles et/ou conduites "orange" en FEUILLERES terrain privé . EUI MED Zone avec câble "orange" pleine terre en terrain privé C.V. No. 1 Commune de Hem Monacu : PLU Plan de détail 1 ; zone avec câble en terrain privé Zone avec câble "Orange " pleine terre en terrain privé . Commune de Hem Monacu : PLU Plan de détail 2 ; zones avec câble "Orange" en terrain privé . WARLENCOURT-EAUCOURT LIGNY-THILLOY LE SARS GUEUDECOURT Voir plan détail 1 MARTINPUICH FLERS 1FS ZOC Voir plan détail 2 LESBOEUFS LONGUEVAL Commune de Flers : PLU BAZENTIN Plan global ; zones avec câbles et/ou conduites "Orange" en terrain privé . GINCHY Commune de Flers : PLU Plan de détail 1 ; zone avec câble en terrain privé. Zone avec câble "Orange" pleine terre en terrain privé Les Quatre 10 12 Haies des Foss¿ Tour du Le Haut dit du Foss¿ d'en-Bas Rural Chemin Zone avec câble "Orange" pleine Entre le Village terre en terrain et le Foss¿ d'en-Bas privé. 1FS A08 ZOC Foss¿ Commune de Flers : PLU Plan de détail 2 ; zone avec câble en terrain privé. -

First World War Journal

Irish Voices from the First World War a blog based on PRONI sources August/September 1916 After the first terrible day on the Somme, the British army’s offensive continued throughout the summer months of 1916. Successive assaults were made on the German positions along the Front with troops from Britain, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and India taking part. In September, the 16th (Irish) Division launched attacks on the villages of Guillemont and Ginchy. More than 4,000 men fell in these assaults. Elsewhere the major Russian offensive in the East ground to a halt and in the south the Italian army launched successful attacks on Austro-Hungarian positions on the Isonzo line at Gorizia. Letter 1: D3503/5/1 – Letter to Corporal George Hackney of Belfast, serving with the Royal Irish Rifles, from Reverend John Pollock, of St Enoch’s Presbyterian Church, concerning his son Paul’s death at the Somme on 1st July 1916. 3rd August 1916. My dear George, Since leaving home three weeks ago I have had no heart to write to anyone, so that you are not an exception. We feel that there is now nothing but the very faintest likelihood of our dear boy turning up, and the suspense has given place to a sense of bitter bereavement. At the same time we do not forget that we gave Paul for the noblest of causes, and he most enthusiastically gave himself. The present war is, on our part, ‘for the defence of the gospel’, the protection, advancement and consolidation of the kingdom of God.