A Welsh Response to the Great War: the 38Th (Welsh) Division on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorial at Contalmaison, France

Item no Report no CPC/ I b )03-ClVke *€DINBVRGH + THE CITY OF EDINBURGH COUNCIL Hearts Great War Memorial Fund - Memorial at Contalmaison, France The City of Edinburgh Council 29 April 2004 Purpose of report 1 This report provides information on the work being undertaken by the Hearts Great War Memorial Fund towards the establishment of a memorial at Contalmaison, France, and seeks approval of a financial contribution from the Council. Main report 2 The Hearts Great War Memorial Committee aims to establish and maintain a physical commemoration in Contalmaison, France, in November this year, of the participation of the Edinburgh l!jthand 16th Battalions of the Royal Scots at the Battle of the Somme. 3 Members of the Regiment had planned the memorial as far back as 1919 but, for a variety of reasons, this was not progressed and the scheme foundered because of a lack of funds. 4 There is currently no formal civic acknowledgement of the two City of Edinburgh Battalions, Hearts Great War Memorial Committee has, therefore, revived the plan to establish, within sight of the graves of those who died in the Battle of the Somme, a memorial to commemorate the sacrifice made by Sir George McCrae's Battalion and the specific role of the players and members of the Heart of Midlothian Football Club and others from Edinburgh and the su rround i ng a reas. 5 It is hoped that the memorial cairn will be erected in the town of Contalmaison, to where the 16thRoyal Scots advanced on the first day of the battle of the 1 Somme in 1916. -

How Will the Coalition End? Cameron and Clegg May Look to the Precedent Set by the 1945 Caretaker Government

How will the coalition end? Cameron and Clegg may look to the precedent set by the 1945 caretaker government blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/how-will-it-end-the-precedent-for-a-caretaker-government-at-the-end-of-the- coalition/ 5/8/2013 Alun Wyburn-Powell provides a historical account of the 1945 caretaker government and argues that it provides a useful model for thinking about when the current coalition might end. Whilst obviously very different situations, there is good logic in parting some months prior to the start of the 2015 campaign for both the LibDems and Tories. It would allow a bit more freedom for the parties to maneuver and might neutralize Labour’s attempt to attack the coalition. Nick Clegg and David Cameron’s press conference in the Rose Garden at 10 Downing Street was the image which characterised the start of the current coalition in May 2010. At that time many people believed that the government was unlikely to last the full parliamentary term. Now, past the halfway mark, most think that it probably will. History is on the side of the coalition surviving to the end. The Lloyd George coalition lasted for six years, in war and peace, from 1916 to 1922. The National Government lasted nine years from 1931 to 1940 and the most recent example, Churchill’s all-party Second World War coalition, lasted five years from 1940 to 1945. Assuming that it does last, how could the current coalition be brought to a neat conclusion, so that the parties do not end up fighting each other in an election campaign, while still in government together? The example of the Caretaker Government at the end of the last coalition in 1945 offers a precedent. -

Tour Sheets Final04-05

Great War Battlefields Study Tour Briefing Notes & Activity Sheets Students Name briefing notes one Introduction The First World War or Great War was a truly terrible conflict. Ignored for many years by schools, the advent of the National Curriculum and the GCSE system reignited interest in the period. Now, thousands of pupils across the United Kingdom study the 1914-18 era and many pupils visit the battlefield sites in Belgium and France. Redevelopment and urban spread are slowly covering up these historic sites. The Mons battlefields disappeared many years ago, very little remains on the Ypres Salient and now even the Somme sites are under the threat of redevelopment. In 25 years time it is difficult to predict how much of what you see over the next few days will remain. The consequences of the Great War are still being felt today, in particular in such trouble spots as the Middle East, Northern Ireland and Bosnia.Many commentators in 1919 believed that the so-called war to end all wars was nothing of the sort and would inevitably lead to another conflict. So it did, in 1939. You will see the impact the war had on a local and personal level. Communities such as Grimsby, Hull, Accrington, Barnsley and Bradford felt the impact of war particularly sharply as their Pals or Chums Battalions were cut to pieces in minutes during the Battle of the Somme. We will be focusing on the impact on an even smaller community, our school. We will do this not so as to glorify war or the part oldmillhillians played in it but so as to use these men’s experiences to connect with events on the Western Front. -

A Breach in the Family

The Lloyd Georges J Graham Jones examines the defections, in the 1950s, of the children of David Lloyd George: Megan to Labour, and her brother Gwilym to the Conservatives. AA breachbreach inin thethe familyfamily G. thinks that Gwilym will go to the right and she became a cogent exponent of her father’s ‘LMegan to the left, eventually. He wants his dramatic ‘New Deal’ proposals to deal with unem- money spent on the left.’ Thus did Lloyd George’s ployment and related social problems. Although op- trusted principal private secretary A. J. Sylvester posed by a strong local Labour candidate in the per- write in his diary entry for April when dis- son of Holyhead County Councillor Henry Jones in cussing his employer’s heartfelt concern over the fu- the general election of , she secured the votes of ture of his infamous Fund. It was a highly prophetic large numbers of Labour sympathisers on the island. comment. The old man evidently knew his children. In , she urged Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin to welcome the Jarrow marchers, and she battled he- Megan roically (although ultimately in vain) to gain Special Megan Lloyd George had first entered Parliament at Assisted Area Status for Anglesey. Megan’s innate only twenty-seven years of age as the Liberal MP for radicalism and natural independence of outlook Anglesey in the We Can Conquer Unemployment gen- grew during the years of the Second World War, eral election of May , the first women mem- which she saw as a vehicle of social change, espe- ber ever to be elected in Wales. -

80Th Division, Summary of Operations in the World

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com -NRLF .3 B 3 11D 80tK ; .5 80TH DIVISION .UMMARY OF OPERATIONS IN THE WORLD WAR PREPARED BY THE . _> , AMERICAN BATTLE MONUMENTS COMMISSION UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTiNG OFFiCE 1944 FOR SALE BY THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS U. S. GOVERNMENT PRINTiNG OFFICE WASHiNGTON 25, D. C. Foreword THE AMER1CAN BATTLE MONUMENTS COMMISSION was created by Congress in 1923 for the purpose of commemorating the serv ices of American forces in Europe during the World War. In the accomplishment of this mission, the Commission has erected suitable memorials in Europe and improved and beautified the eight American cemeteries there. It has also published a book entitled "American Armies and Battlefields in Europe" which gives a concise account of the vital part played by American forces in the World War and detailed information regarding the memorials and cemeteries. In order that the actions of American troops might be accu rately set forth, detailed studies were made of the operations of each division which had front-line battle service. In certain cases studies of sector service were also prepared. It is felt that the results of this research should now be made available to the public. Therefore, these studies are being published in a series of twenty-eight booklets, each booklet devoted to the operations of one division. In these booklets only the active service of the divisions is treated in detail. -

The Militia Gunners

Canadian Military History Volume 21 Issue 1 Article 8 2015 The Militia Gunners J.L. Granatstein Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation J.L. Granatstein "The Militia Gunners." Canadian Military History 21, 1 (2015) This Feature is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : The Militia Gunners The Militia Gunners J.L. Granatstein y general repute, two of the best in 1926 in Edmonton as a boy soldier, Bsenior artillery officers in the Abstract: Two of the best senior got his commission in 193[2], and in Canadian Army in the Second World artillery officers in the Canadian the summer of 1938 was attached Army in the Second World War were War were William Ziegler (1911-1999) products of the militia: William to the Permanent Force [PF] as an and Stanley Todd (1898-1996), both Ziegler (1911-1999) and Stanley instructor and captain. There he products of the militia. Ziegler had Todd (1898-1996). Ziegler served mastered technical gunnery and a dozen years of militia experience as the senior artillery commander in became an expert, well-positioned before the war, was a captain, and was 1st Canadian Infantry Division in Italy to rise when the war started. He from February 1944 until the end of in his third year studying engineering the war. Todd was the senior gunner went overseas in early 1940 with at the University of Alberta when in 3rd Canadian Infantry Division the 8th Field Regiment and was sent his battery was mobilized in the and the architect of the Canadian back to Canada to be brigade major first days of the war. -

The Durham Light Infantry and the Somme 1916

The Durham Light Infantry and The Somme 1916 by John Bilcliffe edited and amended in 2016 by Peter Nelson and Steve Shannon Part 4 The Casualties. Killed in Action, Died of Wounds and Died of Disease. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License You can download this work and share it with others as long as it is credited, but you can’t change it in any way or use it commercially © John Bilcliffe. Email [email protected] Part 4 Contents. 4.1: Analysis of casualties sustained by The Durham Light Infantry on the Somme in 1916. 4.2: Officers who were killed or died of wounds on the Somme 1916. 4.3: DLI Somme casualties by Battalion. Note: The drawing on the front page of British infantrymen attacking towards La Boisselle on 1 July 1916 is from Reverend James Birch's war diary. DCRO: D/DLI 7/63/2, p.149. About the Cemetery Codes used in Part 4 The author researched and wrote this book in the 1990s. It was designed to be published in print although, sadly, this was not achieved during his lifetime. Throughout the text, John Bilcliffe used a set of alpha-numeric codes to abbreviate cemetery names. In Part 4 each soldier’s name is followed by a Cemetery Code and, where known, the Grave Reference, as identified by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Here are two examples of the codes and what they represent: T2 Thiepval Memorial A5 VII.B.22 Adanac Military Cemetery, Miraumont: Section VII, Row B, Grave no. -

University of Maine, World War II, in Memoriam, Volume 1 (A to K)

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine General University of Maine Publications University of Maine Publications 1946 University of Maine, World War II, In Memoriam, Volume 1 (A to K) University of Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/univ_publications Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the History Commons Repository Citation University of Maine, "University of Maine, World War II, In Memoriam, Volume 1 (A to K)" (1946). General University of Maine Publications. 248. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/univ_publications/248 This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in General University of Maine Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF MAINE WORLD WAR II IN MEMORIAM DEDICATION In this book are the records of those sons of Maine who gave their lives in World War II. The stories of their lives are brief, for all of them were young. And yet, behind the dates and the names of places there shines the record of courage and sacrifice, of love, and of a devotion to duty that transcends all thought of safety or of gain or of selfish ambition. These are the names of those we love: these are the stories of those who once walked with us and sang our songs and shared our common hope. These are the faces of our loved ones and good comrades, of sons and husbands. There is no tribute equal to their sacrifice; there is no word of praise worthy of their deeds. -

PROCES VERBAL DU CONSEIL COMMUNAUTAIRE Mercredi 20 Mai 2020

PROCES VERBAL DU CONSEIL COMMUNAUTAIRE Mercredi 20 mai 2020 L’an deux mille vingt, le mercredi vingt mai, à dix-huit heures, le Conseil Communautaire, légalement convoqué, s’est réuni au nombre prescrit par la Loi, en visioconférence. Ont assisté à la visioconférence : Aizecourt le Bas : Mme Florence CHOQUET - Allaines : M. Bernard BOURGUIGNON - Barleux : M. Éric FRANÇOIS – Brie : M. Marc SAINTOT - Bussu : M. Géry COMPERE - Cartigny : M. Patrick DEVAUX - Devise : Mme Florence BRUNEL - Doingt Flamicourt : M. Francis LELIEUR - Epehy : Mme Marie Claude FOURNET, M. Jean-Michel MARTIN- Equancourt : M. Christophe DECOMBLE - Estrées Mons : Mme Corinne GRU – Eterpigny : : M. Nicolas PROUSEL - Etricourt Manancourt : M. Jean- Pierre COQUETTE - Fins : Mme Chantal DAZIN - Ginchy : M. Dominique CAMUS – Gueudecourt : M. Daniel DELATTRE - Guyencourt-Saulcourt : M. Jean-Marie BLONDELLE- Hancourt : M. Philippe WAREE - Herbécourt : M. Jacques VANOYE - Hervilly Montigny : M. Richard JACQUET - Heudicourt : M. Serge DENGLEHEM - Lesboeufs : M. Etienne DUBRUQUE - Liéramont : Mme Véronique VUE - Longueval : M. Jany FOURNIER- Marquaix Hamelet : M. Bernard HAPPE – Maurepas Leforest : M. Bruno FOSSE - Mesnil Bruntel : M. Jean-Dominique PAYEN - Mesnil en Arrouaise : M. Alain BELLIER - Moislains : Mme Astrid DAUSSIN, M. Noël MAGNIER, M. Ludovic ODELOT - Péronne : Mme Thérèse DHEYGERS, Mme Christiane DOSSU, Mme Anne Marie HARLE, M. Olivier HENNEBOIS, , Mme Catherine HENRY, Mr Arnold LAIDAIN, M. Jean-Claude SELLIER, M. Philippe VARLET - Roisel : M. Michel THOMAS, M. Claude VASSEUR – Sailly Saillisel : Mme Bernadette LECLERE - Sorel le Grand : M. Jacques DECAUX - Templeux la Fosse : M. Benoit MASCRE - Tincourt Boucly : M Vincent MORGANT - Villers-Carbonnel : M. Jean-Marie DEFOSSEZ - Villers Faucon : Mme Séverine MORDACQ- Vraignes en Vermandois : Mme Maryse FAGOT. Etaient excusés : Biaches : M. -

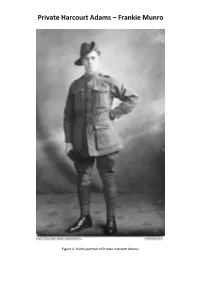

Private Harcourt Adams – Frankie Munro

Private Harcourt Adams – Frankie Munro Figure 1: Studio portrait of Private Harcourt Adams. These are the stories of two brave Tasmanian men. The first of which, my friend’s ancestor, a sailor from Swansea, killed at Pozières in 1916. The second, a lost relative of mine that I discovered through the Frank MacDonald Memorial Prize, also killed at Pozières in 1916. Harcourt (Duke) Adams was born in Swansea on the 8 August 1890 to parents Frederick and Alice Adams. Prior to his enlistment, he was a fireman on board a steamship owned by the Mt. Lyell Co. When his ship was in port in Hobart, he lived with his mother and younger sister, Ivy. His four other sisters, Minnie, Violet, Lilly and Ruby had married and lived elsewhere, and his father tragically passed away several years before the war, so Harcourt was providing the only income for them when he enlisted. Harcourt enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) on the 11 June 1915, aged 24. He was given the service number 2496 and assigned to the 15th Battalion, 7th Reinforcements. Figure 2: 15th Battalion AIF colour patch. On the 17 July 1915, Harcourt embarked from Melbourne on board the HMAT Orsova A67. Several photographs were taken of the ship as it left Port Melbourne, the soldiers can be seen lining the deck, bidding farewell to the crowd, some even climbed the rigging. There is the possibility that one of those men was Harcourt. Figure 3: HMAT Orsova A67 leaving Port Melbourne, 17.07.1915. Figure 4: A closeup shot of the Orsova showing the Australian soldiers on board, 17.07.1915. -

Montage Fiches Rando

Leaflet Walks and hiking trails Haute-Somme and Poppy Country 8 Around the Thiepval Memorial (Autour du Mémorial de Thiepval) Peaceful today, this Time: 4 hours 30 corner of Picardy has become an essential Distance: 13.5 km stage in the Circuit of Route: challenging Remembrance. Leaving from: Car park of the Franco-British Interpretation Centre in Thiepval Thiepval, 41 km north- east of Amiens, 8 km north of Albert Abbeville Thiepval Albert Péronne Amiens n i z a Ham B . C Montdidier © 1 From the car park, head for the Bois d’Authuille. The carnage of 1st July 1916 church. At the crossroads, carry After the campsite, take the Over 58 000 victims in just straight on along the D151. path on your right and continue one day: such is the terrible Church of Saint-Martin with its as far as the village. Turn left toll of the confrontation war memorial built into its right- toward the D151. between the British 4th t Army and the German hand pillar. One of the many 3 Walk up the street opposite s 1st Army, fewer in number military pilgrimages to Poppy (Rue d’Ovillers) and keep going e r but deeply entrenched. Country, the emblematic flower as far as the crossroads. e Their machine guns mowed of the “Tommies”. By going left, you can cut t down the waves of infantrymen n At the cemetery, follow the lane back to Thiepval. i as they mounted attacks. to the left, ignoring adjacent Take the lane going right, go f Despite the disaster suffered paths, as far as the hamlet of through the Bois de la Haie and O by the British, the battle Saint-Pierre-Divion. -

CC De La Haute Somme (Combles - Péronne - Roisel) (Siren : 200037059)

Groupement Mise à jour le 01/07/2021 CC de la Haute Somme (Combles - Péronne - Roisel) (Siren : 200037059) FICHE SIGNALETIQUE BANATIC Données générales Nature juridique Communauté de communes (CC) Commune siège Péronne Arrondissement Péronne Département Somme Interdépartemental non Date de création Date de création 28/12/2012 Date d'effet 31/12/2012 Organe délibérant Mode de répartition des sièges Répartition de droit commun Nom du président M. Eric FRANCOIS Coordonnées du siège Complément d'adresse du siège 23 Avenue de l'Europe Numéro et libellé dans la voie Distribution spéciale Code postal - Ville 80200 PERONNE Téléphone Fax Courriel [email protected] Site internet www.coeurhautesomme.fr Profil financier Mode de financement Fiscalité professionnelle unique Bonification de la DGF non Dotation de solidarité communautaire (DSC) non Taxe d'enlèvement des ordures ménagères (TEOM) oui Autre taxe non Redevance d'enlèvement des ordures ménagères (REOM) non Autre redevance non Population Population totale regroupée 27 799 1/5 Groupement Mise à jour le 01/07/2021 Densité moyenne 59,63 Périmètre Nombre total de communes membres : 60 Dept Commune (N° SIREN) Population 80 Aizecourt-le-Bas (218000123) 55 80 Aizecourt-le-Haut (218000131) 69 80 Allaines (218000156) 460 80 Barleux (218000529) 238 80 Bernes (218000842) 354 80 Biaches (218000974) 391 80 Bouchavesnes-Bergen (218001097) 291 80 Bouvincourt-en-Vermandois (218001212) 151 80 Brie (218001345) 332 80 Buire-Courcelles (218001436) 234 80 Bussu (218001477) 220 80 Cartigny (218001709) 753 80 Cléry-sur-Somme