Against Being Against the Revolving Door

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lloyd Cutler

White House Interview Program DATE: July 8, 1999 INTERVIEWEE: LLOYD CUTLER INTERVIEWER: Martha Kumar With Nancy Kassop MK: May we tape? LC: Yes, but I’d like to have one understanding. I have been misquoted on more than one occasion. I’ll be happy to talk to you about what I think about the transition but I don’t want my name attached to any of it. MK: Okay. So we’ll come back to you for any quotes. We’re going to look at both aspects: the transition itself and then the operations of the office. Working on the theory that one of the things that would be important for people is to understand how an effective operation works, what should they be aiming toward? For example, what is a smooth-running counsel’s office? What are the kinds of relationships that should be established and that sort of thing? So, in addition to looking at the transition, we’re just hoping they’re looking toward effective governance. In your time in Washington, observing many administrations from various distances, you have a good sense of transitions, what works and what doesn’t work. One of the things we want to do is isolate what are the elements of success—just take a number, six elements, five elements—that you think are common to successful transitions. What makes them work? LC: Well, the most important thing to grasp first is how much a White House itself, especially as it starts off after a change in the party occupying the White House, resembles a city hall. -

Reimbursing the Attorney's Fees of Current and Former Federal

(Slip Opinion) Reimbursing the Attorney’s Fees of Current and Former Federal Employees Interviewed as Witnesses in the Mueller Investigation The Department of Justice Representation Guidelines authorize, on a case-by-case basis, the reimbursement of attorney’s fees incurred by a current or former federal govern- ment employee interviewed as a witness in the Mueller Investigation under threat of subpoena about information the person acquired in the course of his government du- ties. October 7, 2020 MEMORANDUM OPINION FOR THE ACTING ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL CIVIL DIVISION You have asked for our opinion on the scope of the Attorney General’s authority to reimburse the attorney’s fees of federal employees who were interviewed as witnesses in connection with the investigation by Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller, III into possible Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election (“Mueller Investigation”). The Civil Division reviews requests for such reimbursement under long-standing Department of Justice (“Department”) regulations. See 28 C.F.R. §§ 50.15–50.16. You have asked specifically how certain elements of section 50.15 apply to the Mueller Investigation: (1) whether a person interviewed as a witness in the Mueller Investigation under threat of subpoena should be viewed as having been “subpoenaed,” id. § 50.15(a); (2) whether a witness inter- viewed about information acquired in the course of the witness’s federal employment appears in an “individual capacity,” id.; and (3) what factors should be considered in evaluating whether the reimbursement of the attorney’s fees of such a witness is “in the interest of the United States,” id. -

RLB Letterhead

6-25-14 White Paper in support of the Robert II v CIA and DOJ plaintiff’s June 25, 2014 appeal of the June 2, 2014 President Reagan Library FOIA denial decision of the plaintiff’s July 27, 2010 NARA MDR FOIA request re the NARA “Perot”, the NARA “Peter Keisler Collection”, and the NARA “Robert v National Archives ‘Bulky Evidence File” documents. This is a White Paper (WP) in support of the Robert II v CIA and DOJ, cv 02-6788 (Seybert, J), plaintiff’s June 25, 2014 appeal of the June 2, 2014 President Reagan Library FOIA denial decision of the plaintiff’s July 27, 2010 NARA MDR FOIA request. The plaintiff sought the release of the NARA “Perot”, the NARA “Peter Keisler Collection”, and the NARA “Robert v National Archives ‘Bulky Evidence File” documents by application of President Obama’s December 29, 2009 E.O. 13526, Classified National Security Information, 75 F.R. 707 (January 5, 2010), § 3.5 Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR). On June 2, 2014, President Reagan Library Archivist/FOIA Coordinator Shelly Williams rendered a Case #M-425 denial decision with an attached Worksheet: This is in further response to your request for your Mandatory Review request for release of information under the provisions of Section 3.5 of Executive Order 13526, to Reagan Presidential records pertaining to Ross Perot doc re report see email. These records were processed in accordance with the Presidential Records Act (PRA), 44 U.S.C. §§ 2201-2207. Id. Emphasis added. The Worksheet attachment to the decision lists three sets of Keisler, Peter: Files with Doc ## 27191, 27192, and 27193 notations. -

Spring 2021 Spring 2021

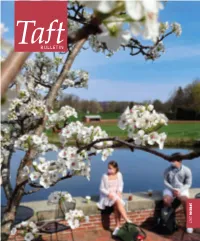

SPRING 2021 SPRING 2021 INSIDE 42 Unscripted: How filmmakers Peter Berg ’80 and Jason Blum ’87 evolved during a year of COVID-19 By Neil Vigdor ’95 c 56 Confronting the Pandemic Dr. Paul Ehrlich ’62 and his work as a New York City allergist-immunologist By Bonnie Blackburn-Penhollow ’84 b OTHER DEPARTMENTS 3 On Main Hall 5 Social Scene 6 Belonging 24/7 Elena Echavarria ’21 8 Alumni Spotlight works on a project in 20 In Print Advanced Ceramics 26 Around the Pond class, where students 62 do hands-on learning Class Notes in the ceramics studio 103 Milestones with teacher Claudia 108 Looking Back Black. ROBERT FALCETTI 8 On MAIN HALL A WORD FROM HEAD Managing Stress in Trying Times OF SCHOOL WILLY MACMULLEN ’78 This is a column about a talk I gave and a talk I heard—and about how SPRING 2021 ON THE COVER schools need to help students in managing stress. Needless to say, this Volume 91, Number 2 Students enjoyed the warm spring year has provided ample reason for this to be a singularly important weather and the beautiful flowering EDITOR trees on the Jig Patio following focus for schools. Linda Hedman Beyus Community Time. ROBERT FALCETTI In September 2018, during my opening remarks to the faculty, I spoke about student stress, and how I thought we needed to think about DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Kaitlin Thomas Orfitelli it in new ways. I gave that talk because it was clear to me that adolescents today were ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS experiencing stress and managing stress in different ways than when I Debra Meyers began teaching and even when I began as head of school just 20 years PHOTOGRAPHY ago. -

The Specially Investigated President

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 1998 The pS ecially Investigated President Charles Tiefer University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the National Security Law Commons, and the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation The peS cially Investigated President, 5 U. Chi. L. Sch. Roundtable 143 (1998) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES The Specially Investigated President CHARLES TIEFER t 1. Introduction For the past decade a series of long-term investigations by Independent Counselsl occurred in parallel with those of special congressional committees.2 These investigations have resulted in the imposition of a new legal status for the president. This new status re-orients the long-standing tension that exists between the bounds of presidential power and the president's vulnerability to legal suit.3 The parallel special inquiries into the subjects of Iran-Contra, t. Charles Tiefer is Associate Professor of Law at the University of Baltimore School of Law. He served as Solicitor and Deputy General Counsel for the House .of Represen tatives from 1984 to 1995. He received his J.D. from Harvard Law School in 1977 and his B.A. from Columbia University in 1974. -

Download Original 437.74 KB

The Confirmation Process for Lower Federal Court Appointments in the Clinton and W. Bush Administrations: A Comparative Analysis Matthew R. Batzel Submitted to the Department of Government, Franklin and Marshall College Advisor: D. Grier Stephenson, Jr. Submitted: April 29, 2005 Defended: May 4, 2005 Expected Graduation Date: May 15, 2005 Table of Contents Introduction 4 Overview of paper 5 Previous Research 6 Research methods 7 Background- Constitutional Convention 8 U.S. District Courts 10 U.S. Courts of Appeals 10 Process 10 History of Nominations 12 Clinton’s years with United Government 18 Structure 18 Process 18 Results 19 District Court Appointees 20 Appeals Court Appointees 21 Extreme Judges? 21 Analysis 22 Clinton’s years with Divided Government 22 Structure 23 Process 23 Results 26 District Court Appointees 26 Appeals Court Appointees 29 Sampling of Judicial Nominees 30 The Effect of Presidential Politics 32 Politics 32 Fourth Circuit 33 Blocking nominees 33 Confirmation delay 34 Scrutinizing women and minorities? 35 Clinton effect 36 Use of Blue Slip System 36 Ronnie White 37 Congressional Record 38 Unprecedented? 41 Analysis 42 Bush’s years with Divided Government 43 Structure 43 Process 45 Departure from Status Quo 45 Results 47 District Court Appointees 48 Appeals Court Appointees 49 2 Sampling of Judicial Nominees 50 Politics 52 Unprecedented? 55 Congressional Record 56 Analysis 57 Bush’s years with United Government 58 Structure and Process 58 Results 58 Sampling of Judicial Nominees 59 Politics 60 Unprecedented? 62 The Filibuster 64 Congressional Record 66 Analysis 68 Explanation of contentious judicial debate 69 Conclusion 71 Future 72 Bibliography 74 Endnotes 76 3 Introduction Judicial appointments help presidents leave their mark on the nation. -

Letter from House Chairmen Cummings, Engel

(llnngreafi at the finiteh fitatea maahingtmt. EQ‘L 21.1515 October 4, 2019 The Honorable John Michael Mulvaney Acting Chief of Staff to the President The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Ave, NW. Washington, DC 20500 Dear Mr. Mulvaney: Pursuant to the House of Representatives’ impeachment inquiry, we are hereby transmitting a subpoena that compels you to produce documents set forth in the accompanying schedu1e by October 18, 2019. This subpoena is being issued by the Committee on Oversight and Reform under the Rules of the House of Representatives in exercise of its oversight and legislative jurisdiction and after consultation with the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence and the Committee on Foreign Affairs. The subpoenaed documents shall be collected as part of the House’s impeachment inquiry and shared among the Committees, as well as with the Committee on the Judiciary as appropriate.1 Your failure or refusal to comply with the subpoena, including at the direction or behest of the President or others at the White House, shall constitute evidence of obstruction of the House’s impeachment inquiry and may be used as an adverse inference against you and the President. The Committees are investigating the extent to which President Trump jeopardized national security by pressing Ukraine to interfere with our 2020 election and by withholding security assistance provided by Congress to help Ukraine counter Russian aggression, as well as any efforts to cover up these matters. During a press conference on Wednesday, President Trump was asked if he would cooperate with the House impeachment inquiry. He responded, “I always cooperate.”2 President Trump’s claim is patently false. -

The White House Counsel's Office

THE WHITE HOUSE TRANSITION PROJECT 1997-2021 Smoothing the Peaceful Transfer of Democratic Power REPORT 2021—28 THE WHITE HOUSE COUNSEL MaryAnne Borrelli, Connecticut College Karen Hult, Virginia Polytechnic Institute Nancy Kassop, State University of New York–New Paltz Kathryn Dunn Tenpas, Brookings Institution Smoothing the Peaceful Transfer of Democratic Power WHO WE ARE & WHAT WE DO The White House Transition Project. Begun in 1998, the White House Transition Project provides information about individual offices for staff coming into the White House to help streamline the process of transition from one administration to the next. A nonpartisan, nonprofit group, the WHTP brings together political science scholars who study the presidency and White House operations to write analytical pieces on relevant topics about presidential transitions, presidential appointments, and crisis management. Since its creation, it has participated in the 2001, 2005, 2009, 2013, 2017, and now the 2021. WHTP coordinates with government agencies and other non-profit groups, e.g., the US National Archives or the Partnership for Public Service. It also consults with foreign governments and organizations interested in improving governmental transitions, worldwide. See the project at http://whitehousetransitionproject.org The White House Transition Project produces a number of materials, including: • WHITE HOUSE OFFICE ESSAYS: Based on interviews with key personnel who have borne these unique responsibilities, including former White House Chiefs of Staff; Staff Secretaries; Counsels; Press Secretaries, etc. , WHTP produces briefing books for each of the critical White House offices. These briefs compile the best practices suggested by those who have carried out the duties of these office. With the permission of the interviewees, interviews are available on the National Archives website page dedicated to this project: • *WHITE HOUSE ORGANIZATION CHARTS. -

711 My Knowledge of Sam Alito Is Based Almost Entirely on My Per

711 My knowledge of Sam Alito is based almost entirely on my per- sonal acquaintance with the man, but since his nomination to the Supreme Court, I have attempted, as have many others, to glean at least a sense of his judicial temperament by reading a few of his opinions. I haven’t read many. I haven’t made a systematic study of them, but the ones that I have read suggest to me rather strong- ly that the judicial temperament that I discern in these opinions is entirely consistent with the human temperament of the man I came to know and admire more than 30 years ago. The temperament of the judge, as I see it, is marked by modesty, by caution, by deference to others in different roles with different responsibilities, by an acute appreciation of the limitations of his own office, and by a deep and abiding respect for the past. There is a name that we give to all of these qualities, taken to- gether. We call them judiciousness, and in calling them that we recognize that they are the special virtues of a judge. Judge Alito has been a judicious judge and my confidence that he will be a ju- dicious Justice is based on my personal knowledge of the man and my belief that his judicial temperament is rooted in his human character, which is the deepest and strongest foundation it could have. Thank you very much. [The prepared statement of Mr. Kronman appears as a submis- sion for the record.] Chairman SPECTER. Thank you very much, Professor Kronman. -

THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON May20, 2019

THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON May20, 2019 The Honorable Jerrold Nadler Chairman Committee on the Judiciary United States House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Chairman Nadler: I write in further reference to the subpoenaissued by the Committee on the Judiciary of the United States House of Representatives (the “Committee”) to Donald F. MeGahn II on April 22, 2019. My previousletter, dated May 7, 2019, informed you that Acting Chief of Staff to the President Mick Mulvaney had directed Mr. McGahn not to produce the White House records sought by the subpoena because they remain subject to the control of the White House and implicate significant Executive Branch confidentiality interests and executive privilege. Accordingly, ] asked that the Committee direct any request for such records to the White House. The subpoenaalso directs Mr. McGahn to appearto testify before the Committee at 10:00 a.m. on Tuesday, May 21, 2019. The Department of Justice (the “Depariment”) has advised me that Mr. McGahn is absolutely immune from compelled congressional testimony with respect to matters occurring during his service as a senior adviser to the President. See Memorandum for Pat A. Cipollone, Counsel to the President, from Steven A. Engel, Assistant Attorney General, Office of Legal Counsel, Re: Testimonial Immunity Before Congress ofthe Former Counselto the President (May 20, 2019). The Department has long taken the position—across administrationsof both political parties—that “the President and his immediate advisers are absolutely immune from testimonial compulsion by a Congressional committee.” Jmmunity of the Former Counselto the President from Compelled Congressional Testimony, 31 Op. O.L.C. -

Chapter 10 on "Testimony by White House Officials"

The Politics of Executive Privilege Louis Fisher Carolina Academic Press Durham, North Carolina Copyright © 2004 Louis Fisher All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fisher, Louis The politics of executive privilege / by Louis Fisher p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-89089-416-7 (paperback) ISBN 0-89089-541-4 (hardcover) 1. Executive privilege (Government information—United States. 2. Executive power—United States. 3. Legislative power—United States. 4. Separation of powers—United States. I. Title. JK468.S4F57 2003 352.23'5'0973—dc22 2003060238 Carolina Academic Press 700 Kent Street Durham, NC 27701 Telephone (919)489-7486 Fax (919)493-5668 www.cap-press.com Cover art by Scot C. McBroom for the Historic American Buildings Survey, Na- tional Parks Service. Library of Congress call number HABS, DC, WASH, 134-1. Printed in the United States of America 10 Testimony by White House Officials Administrations will often claim that White House aides are exempt from appearing before congressional committees. White House Counsels advise lawmakers that “it is a longstanding principle, rooted in the Constitutional separation of powers and the authority vested in the President by Article II of the Constitution, that White House officials generally do not testify before Congress, except in extraordinary circumstances not present here.”1 Take note of the two qualifications: “generally” and “except in extraordinary circum- stances.” Caution here is well advised. Although White House aides do not testify on a regular basis, under cer- tain conditions they do, and in large numbers. Intense and escalating politi- cal pressures may convince the White House that the President is best served by having these aides testify to ventilate an issue fully, hoping to scotch sus- picions of a cover-up or criminal conduct. -

Congressional Inquests: Suffocating the Constitutional Preogative of Executive Privilege Randall K

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1997 Congressional Inquests: Suffocating the Constitutional Preogative of Executive Privilege Randall K. Miller Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Randall K., "Congressional Inquests: Suffocating the Constitutional Preogative of Executive Privilege" (1997). Minnesota Law Review. 2143. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/2143 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Congressional Inquests: Suffocating the Constitutional Prerogative of Executive Privilege Randall K. Miller* [We just simply can't have another Watergate, and another destroyed administration. So I think the Presidentneeds to jettison any thought of executive privilege. - Sen. Howard Baker' IY]ou aren't President;you are temporarily custodian of an institu- tion, the Presidency. And you don't have any right to do away with any of the prerogativesof that institution, and one of those is executive privilege. And this is what was being attacked by the Congress. - President Ronald Reagan2 In a country where people are presumed innocent, the Presidentisn't. You've got to go prove your innocence .... - President Bill Clinton3 * Associate, Kirkpatrick & Lockhart LLP; J.D., George Washington University Law School, 1996. For their invaluable guidance and personal sup- port, I wish to pay special thanks to Robert Park, Beth Nolan, and Chip Lupu. I am also indebted to Harold H.