Missing White House E Mail: a Whistleblowing Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lloyd Cutler

White House Interview Program DATE: July 8, 1999 INTERVIEWEE: LLOYD CUTLER INTERVIEWER: Martha Kumar With Nancy Kassop MK: May we tape? LC: Yes, but I’d like to have one understanding. I have been misquoted on more than one occasion. I’ll be happy to talk to you about what I think about the transition but I don’t want my name attached to any of it. MK: Okay. So we’ll come back to you for any quotes. We’re going to look at both aspects: the transition itself and then the operations of the office. Working on the theory that one of the things that would be important for people is to understand how an effective operation works, what should they be aiming toward? For example, what is a smooth-running counsel’s office? What are the kinds of relationships that should be established and that sort of thing? So, in addition to looking at the transition, we’re just hoping they’re looking toward effective governance. In your time in Washington, observing many administrations from various distances, you have a good sense of transitions, what works and what doesn’t work. One of the things we want to do is isolate what are the elements of success—just take a number, six elements, five elements—that you think are common to successful transitions. What makes them work? LC: Well, the most important thing to grasp first is how much a White House itself, especially as it starts off after a change in the party occupying the White House, resembles a city hall. -

Reimbursing the Attorney's Fees of Current and Former Federal

(Slip Opinion) Reimbursing the Attorney’s Fees of Current and Former Federal Employees Interviewed as Witnesses in the Mueller Investigation The Department of Justice Representation Guidelines authorize, on a case-by-case basis, the reimbursement of attorney’s fees incurred by a current or former federal govern- ment employee interviewed as a witness in the Mueller Investigation under threat of subpoena about information the person acquired in the course of his government du- ties. October 7, 2020 MEMORANDUM OPINION FOR THE ACTING ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL CIVIL DIVISION You have asked for our opinion on the scope of the Attorney General’s authority to reimburse the attorney’s fees of federal employees who were interviewed as witnesses in connection with the investigation by Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller, III into possible Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election (“Mueller Investigation”). The Civil Division reviews requests for such reimbursement under long-standing Department of Justice (“Department”) regulations. See 28 C.F.R. §§ 50.15–50.16. You have asked specifically how certain elements of section 50.15 apply to the Mueller Investigation: (1) whether a person interviewed as a witness in the Mueller Investigation under threat of subpoena should be viewed as having been “subpoenaed,” id. § 50.15(a); (2) whether a witness inter- viewed about information acquired in the course of the witness’s federal employment appears in an “individual capacity,” id.; and (3) what factors should be considered in evaluating whether the reimbursement of the attorney’s fees of such a witness is “in the interest of the United States,” id. -

White House Compliance with Committee Subpoenas Hearings

WHITE HOUSE COMPLIANCE WITH COMMITTEE SUBPOENAS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 6 AND 7, 1997 Serial No. 105–61 Printed for the use of the Committee on Government Reform and Oversight ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 45–405 CC WASHINGTON : 1998 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Jan 31 2003 08:13 May 28, 2003 Jkt 085679 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 E:\HEARINGS\45405 45405 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT DAN BURTON, Indiana, Chairman BENJAMIN A. GILMAN, New York HENRY A. WAXMAN, California J. DENNIS HASTERT, Illinois TOM LANTOS, California CONSTANCE A. MORELLA, Maryland ROBERT E. WISE, JR., West Virginia CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut MAJOR R. OWENS, New York STEVEN SCHIFF, New Mexico EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York CHRISTOPHER COX, California PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida GARY A. CONDIT, California JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York STEPHEN HORN, California THOMAS M. BARRETT, Wisconsin JOHN L. MICA, Florida ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, Washington, THOMAS M. DAVIS, Virginia DC DAVID M. MCINTOSH, Indiana CHAKA FATTAH, Pennsylvania MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland JOE SCARBOROUGH, Florida DENNIS J. KUCINICH, Ohio JOHN B. SHADEGG, Arizona ROD R. BLAGOJEVICH, Illinois STEVEN C. LATOURETTE, Ohio DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois MARSHALL ‘‘MARK’’ SANFORD, South JOHN F. TIERNEY, Massachusetts Carolina JIM TURNER, Texas JOHN E. -

American History: President Clinton's Legal Problems

08 March 2012 | MP3 at voaspecialenglish.com American History: President Clinton's Legal Problems AP President Clinton thanks Democrats in the House of Representatives who opposed his impeachment, as first lady Hillary Rodham Clinton watches, on December 19, 1998 STEVE EMBER: Welcome to THE MAKING OF A NATION – American history in VOA Special English. I'm Steve Ember. This week in our series, we continue the story of America's forty-second president, Bill Clinton. He was a popular and successful president who was re- elected in nineteen ninety-six. But he also became only the second president in American history ever to be put on trial in Congress. (MUSIC) Clinton's past in Arkansas became the source of accusations and questions about his character as he was running for president. These included questions about financial dealings with a land development company called Whitewater. In January of nineteen ninety-four, President Clinton asked Attorney General Janet Reno to appoint an independent lawyer to lead an investigation. She named 2 a Republican, but some critics said her choice was too friendly to the Clinton administration. He was replaced by another Republican, Kenneth Starr. In nineteen ninety-five the Senate Judiciary Committee began its own investigation of the president. The committee later reported that it had not found evidence of any crimes. However, because the committee was led by Democrats, there was continuing suspicion of the president among Republicans. The main cause of that suspicion dated back to a purchase of land in Arkansas years earlier. Bill and Hillary Clinton had bought the land in nineteen seventy eight -- the year he was first elected governor of that state. -

RLB Letterhead

6-25-14 White Paper in support of the Robert II v CIA and DOJ plaintiff’s June 25, 2014 appeal of the June 2, 2014 President Reagan Library FOIA denial decision of the plaintiff’s July 27, 2010 NARA MDR FOIA request re the NARA “Perot”, the NARA “Peter Keisler Collection”, and the NARA “Robert v National Archives ‘Bulky Evidence File” documents. This is a White Paper (WP) in support of the Robert II v CIA and DOJ, cv 02-6788 (Seybert, J), plaintiff’s June 25, 2014 appeal of the June 2, 2014 President Reagan Library FOIA denial decision of the plaintiff’s July 27, 2010 NARA MDR FOIA request. The plaintiff sought the release of the NARA “Perot”, the NARA “Peter Keisler Collection”, and the NARA “Robert v National Archives ‘Bulky Evidence File” documents by application of President Obama’s December 29, 2009 E.O. 13526, Classified National Security Information, 75 F.R. 707 (January 5, 2010), § 3.5 Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR). On June 2, 2014, President Reagan Library Archivist/FOIA Coordinator Shelly Williams rendered a Case #M-425 denial decision with an attached Worksheet: This is in further response to your request for your Mandatory Review request for release of information under the provisions of Section 3.5 of Executive Order 13526, to Reagan Presidential records pertaining to Ross Perot doc re report see email. These records were processed in accordance with the Presidential Records Act (PRA), 44 U.S.C. §§ 2201-2207. Id. Emphasis added. The Worksheet attachment to the decision lists three sets of Keisler, Peter: Files with Doc ## 27191, 27192, and 27193 notations. -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CARA LESLIE ALEXANDER, ) et al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) Civil No. 96-2123 ) 97-1288 ) (RCL) FEDERAL BUREAU OF ) INVESTIGATION, et al., ) ) Defendants. ) ) MEMORANDUM AND ORDER This matter comes before the court on Plaintiffs’ Motion [827] to Compel Answers to Plaintiffs’ First Set of Interrogatories to the Executive Office of the President Pursuant to Court Order of April 13, 1998. Upon consideration of this motion, and the opposition and reply thereto, the court will GRANT the plaintiffs’ motion. I. Background The underlying allegations in this case arise from what has become popularly known as “Filegate.” Plaintiffs allege that their privacy interests were violated when the FBI improperly handed over to the White House hundreds of FBI files of former political appointees and government employees from the Reagan and Bush Administrations. This particular dispute revolves around interrogatories pertaining to Mike McCurry, Ann Lewis, Rahm Emanuel, Sidney Blumenthal and Bruce Lindsey. Plaintiffs served these interrogatories pertaining to these five current or former officials on May 13, 1999. The EOP responded on July 16, 1999. Plaintiffs now seek to compel further answers to the following lines of questioning: 1. Any and all knowledge these officials have, including any meetings held or other communications made, about the obtaining of the FBI files of former White House Travel Office employees Billy Ray Dale, John Dreylinger, Barney Brasseux, Ralph Maughan, Robert Van Eimerren, and John McSweeney (Interrogatories 11, 35, 40 and 47). 2. Any and all knowledge these officials have, including any meetings held or other communications made, about the release or use of any documents between Kathleen Willey and President Clinton or his aides, or documents relating to telephone calls or visits 2 between Willey and the President or his aides (Interrogatories 15, 37, and 42). -

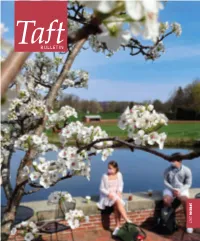

Spring 2021 Spring 2021

SPRING 2021 SPRING 2021 INSIDE 42 Unscripted: How filmmakers Peter Berg ’80 and Jason Blum ’87 evolved during a year of COVID-19 By Neil Vigdor ’95 c 56 Confronting the Pandemic Dr. Paul Ehrlich ’62 and his work as a New York City allergist-immunologist By Bonnie Blackburn-Penhollow ’84 b OTHER DEPARTMENTS 3 On Main Hall 5 Social Scene 6 Belonging 24/7 Elena Echavarria ’21 8 Alumni Spotlight works on a project in 20 In Print Advanced Ceramics 26 Around the Pond class, where students 62 do hands-on learning Class Notes in the ceramics studio 103 Milestones with teacher Claudia 108 Looking Back Black. ROBERT FALCETTI 8 On MAIN HALL A WORD FROM HEAD Managing Stress in Trying Times OF SCHOOL WILLY MACMULLEN ’78 This is a column about a talk I gave and a talk I heard—and about how SPRING 2021 ON THE COVER schools need to help students in managing stress. Needless to say, this Volume 91, Number 2 Students enjoyed the warm spring year has provided ample reason for this to be a singularly important weather and the beautiful flowering EDITOR trees on the Jig Patio following focus for schools. Linda Hedman Beyus Community Time. ROBERT FALCETTI In September 2018, during my opening remarks to the faculty, I spoke about student stress, and how I thought we needed to think about DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Kaitlin Thomas Orfitelli it in new ways. I gave that talk because it was clear to me that adolescents today were ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS experiencing stress and managing stress in different ways than when I Debra Meyers began teaching and even when I began as head of school just 20 years PHOTOGRAPHY ago. -

The Keep Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep 1996 Press Releases 4-4-1996 04/04/1996 - Zeifman To Offer New Theories About Watergate Scandal.pdf University Marketing and Communications Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/press_releases_1996 Recommended Citation University Marketing and Communications, "04/04/1996 - Zeifman To Offer New Theories About Watergate Scandal.pdf" (1996). 1996. 93. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/press_releases_1996/93 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Press Releases at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1996 by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 96-100 April 4, 1996 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: ZEIFMAN TO OFFER NEW THEORIES ABOUT WATERGATE SCANDAL CHARLESTON -- Theories and observations about what really took place in Washington during the Richard Nixon impeachment proceedings will be the topic of a public presentation by former House Judiciary Committee chief counsel Jerry Zeifman at 3 p.m. Monday in Eastern Illinois University's Coleman Hall Auditorium. During his talk, Zeifman will share information from his recently published book, "Without Honor: The Impeachment of President Nixon and the Crimes of Camelot," which gives a personal account of the judiciary process using first-hand material from November 1973 through August 1974 to show how the historic impeachment inquiry was tainted. Zeifman's book is based primarily on an 800-page diary he kept at the time, describing the actions, ethical and otherwise, of key impeachment figures such as Nixon; John Doar, special counsel to the inquiry and formerly a key figure in Robert Kennedy's Justice Department; and Doar aide Hillary Rod ham (now the First Lady) and her fellow staffer Bernard Nussbaum, who recently resigned as President Clinton's -more- ADD 1/1/1/1 ZEIFMAN chief White House counsel. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College of The

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts CITIES AT WAR: UNION ARMY MOBILIZATION IN THE URBAN NORTHEAST, 1861-1865 A Dissertation in History by Timothy Justin Orr © 2010 Timothy Justin Orr Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 The dissertation of Timothy Justin Orr was reviewed and approved* by the following: Carol Reardon Professor of Military History Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Director of Graduate Studies in History Mark E. Neely, Jr. McCabe-Greer Professor in the American Civil War Era Matthew J. Restall Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Colonial Latin American History, Anthropology, and Women‘s Studies Carla J. Mulford Associate Professor of English *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT During the four years of the American Civil War, the twenty-three states that comprised the Union initiated one of the most unprecedented social transformations in U.S. History, mobilizing the Union Army. Strangely, scholars have yet to explore Civil War mobilization in a comprehensive way. Mobilization was a multi-tiered process whereby local communities organized, officered, armed, equipped, and fed soldiers before sending them to the front. It was a four-year progression that required the simultaneous participation of legislative action, military administration, benevolent voluntarism, and industrial productivity to function properly. Perhaps more than any other area of the North, cities most dramatically felt the affects of this transition to war. Generally, scholars have given areas of the urban North low marks. Statistics refute pessimistic conclusions; northern cities appeared to provide a higher percentage than the North as a whole. -

The Clinton Administration and the Erosion of Executive Privilege Jonathan Turley

Maryland Law Review Volume 60 | Issue 1 Article 11 Paradise Losts: the Clinton Administration and the Erosion of Executive Privilege Jonathan Turley Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan Turley, Paradise Losts: the Clinton Administration and the Erosion of Executive Privilege, 60 Md. L. Rev. 205 (2001) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol60/iss1/11 This Conference is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PARADISE LOST: THE CLINTON ADMINISTRATION AND THE EROSION OF EXECUTIVE PRIVILEGE JONATHAN TuRLEY* INTRODUCTION In Paradise Lost, Milton once described a "Serbonian Bog ... [w]here Armies whole have sunk."' This illusion could have easily been taken from the immediate aftermath of the Clinton crisis. On a myriad of different fronts, the Clinton defense teams advanced sweep- ing executive privilege arguments, only to be defeated in a series of judicial opinions. This "Serbonian Bog" ultimately proved to be the greatest factor in undoing efforts to combat inquiries into the Presi- dent's conduct in the Lewinsky affair and the collateral scandals.2 More importantly, it proved to be the undoing of years of effort to protect executive privilege from risky assertions or judicial tests.' In the course of the Clinton litigation, courts imposed a series of new * J.B. & Maurice C. -

Presidential Files; Folder: 10/26/77; Container 48

10/26/77 Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 10/26/77; Container 48 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf THE PRESIDENT 1 S SCHEDU;LE Wednesday - October 26, 1977 • 8:15 Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski - The Oval Office. 8:45 Mr. Frank Moore The Oval Office. 10:30 Mr. Jody Powell The oval Office. 11:00 Senator Gaylord Nelson. (Mr. Frank Moore). (30 min.) The oval Oftice. 12:30 Drop-by Octoberfest - The South Grounds. (10. min.) 1:30 Secretary Juanita Kreps~ (Mr. Jack Watson). (15 min.) The Oval Office. 2:00 Congressman Toby Moffett et al. (30 min.) · (l-1r. Frank Moore) - The Cabinet Room. ; •.. ... :'•,' October 26, 1977 ,. I •I . ,'.,..... - ' .. ~ ~ ~- · ., ' I. ~ (,' J, . .. .; . ' • -~ I I i ; :· . To ·sena'tor .Charles.. l'1athias ' I, II • j j I : ~ o ; t '1 .t ; • i ' . , . , ' I I '• ' ', t ~. ~ I apprecla ~~, _;y(~~r ,1 ;ie,t te7 concerning Camp David, and ,ag;t;"ee , Wl. th. your comnien ts about the b~atitt~oi'~he Catoctin Mountains. The years you"hav~·~pent in this area certainly have been exciting and good. I am intt~rosted in learning more about Camp David~ and ·look, fonvard to hearing of your cxperien'ces in Frederick County. Sincerelyi IJ' '. ' t '. I .·~ . 'J~he Honorable Charles ;l'-~'?R~. Na~hias, Jr.· United States Senate ,... r Washington, D.C. 20510. ;· '_,; '··.' ,. ·I ' I ~ )·. ''\' ,. JC/sc . ,;, ' ;I } .. ~' .~.' . CJmADLJI!IIl!l xcc. MA.TEnrAS, J:a. UN:I'Il'BD 18T.A'll"ll!!I!S §BN.ATJBI October 14, 1977 ~~~.,., CONGRESSIONA~ LIAISON Dear Mr. -

The Politics of the Clinton Impeachment and the Death of the Independent Counsel Statute: Toward Depoliticization

Volume 102 Issue 1 Article 5 September 1999 The Politics of the Clinton Impeachment and the Death of the Independent Counsel Statute: Toward Depoliticization Marjorie Cohn Thomas Jefferson School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr Part of the Courts Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Marjorie Cohn, The Politics of the Clinton Impeachment and the Death of the Independent Counsel Statute: Toward Depoliticization, 102 W. Va. L. Rev. (1999). Available at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr/vol102/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the WVU College of Law at The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Virginia Law Review by an authorized editor of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cohn: The Politics of the Clinton Impeachment and the Death of the Inde THE POLITICS OF THE CLINTON IMPEACHMENT AND THE DEATH OF THE INDEPENDENT COUNSEL STATUTE: TOWARD DEPOLITICIZATION Marjorie Cohn I. INTRODUCTION .........................................................................59 II. THE ANDREW JOHNSON IMPEACHMENT ..................................60 III. TE LEGACY OF WATERGATE .................................................60 IV. THE POLITICAL APPOINTMENT OF AN "INDEPENDENT COUNSEL"... ..............................................................................................63 V. STARR'S W AR ..........................................................................66