Dialectal Features

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full House Tv Show Episodes Free Online

Full house tv show episodes free online Full House This is a story about a sports broadcaster later turned morning talk show host Danny Tanner and his three little Episode 1: Our Very First Show.Watch Full House Season 1 · Season 7 · Season 1 · Season 2. Full House - Season 1 The series chronicles a widowed father's struggles of raising Episode Pilot Episode 1 - Pilot - Our Very First Show Episode 2 - Our. Full House - Season 1 The series chronicles a widowed father's struggles of raising his three young daughters with the help of his brother-in-law and his. Watch Full House Online: Watch full length episodes, video clips, highlights and more. FILTER BY SEASON. All (); Season 8 (24); Season 7 (24); Season. Full House - Season 8 The final season starts with Comet, the dog, running away. The Rippers no longer want Jesse in their band. D.J. ends a relationship with. EPISODES. Full House. S1 | E1 Our Very First Show. S1 | E1 Full House. Full House. S1 | E2 Our Very First Night. S1 | E2 Full House. Full House. S1 | E3 The. Watch Series Full House Online. This is a story about a sports Latest Episode: Season 8 Episode 24 Michelle Rides Again (2) (). Season 8. Watch full episodes of Full House and get the latest breaking news, exclusive videos and pictures, episode recaps and much more at. Full House - Season 5 Season 5 opens with Jesse and Becky learning that Becky is carrying twins; Michelle and Teddy scheming to couple Danny with their. Full House (). 8 Seasons available with subscription. -

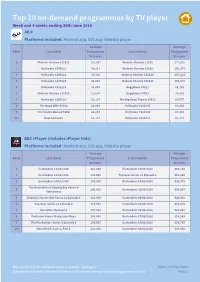

Top 10 On-Demand Programmes by TV Player Week and 4 Weeks Ending 26Th June 2016 All 4 Platforms Included: Android App, Ios App, Website Player

Top 10 on-demand programmes by TV player Week and 4 weeks ending 26th June 2016 All 4 Platforms included: Android app, iOS app, Website player Average Average Rank Last week Programme Last 4 weeks Programme Streams Streams 1 Made In Chelsea S11E11 191,007 Made In Chelsea S11E8 277,592 2 Hollyoaks S25E122 49,911 Made In Chelsea S11E9 252,379 3 Hollyoaks S25E123 44,792 Made In Chelsea S11E10 237,223 4 Hollyoaks S25E124 43,656 Made In Chelsea S11E11 191,070 5 Hollyoaks S25E125 38,009 Gogglebox S7E17 81,725 6 Made In Chelsea S11E10 32,664 Gogglebox S7E16 78,862 7 Hollyoaks S25E126 32,197 The Big Bang Theory S9E22 69,577 8 The Good Wife S7E22 23,663 Hollyoaks S25E107 69,108 9 First Dates Abroad S1E2 22,253 Hollyoaks S25E108 67,253 10 New Girl S5E4 21,712 Hollyoaks S25E111 67,247 BBC iPlayer (includes iPlayer Kids) Platforms included: Android app, iOS app, Website player Average Average Rank Last week Programme Last 4 weeks Programme Streams Streams 1 Eastenders 21/06/2016 361,544 Eastenders 10/06/2016 455,194 2 Eastenders 23/06/2016 298,540 Top Gear Series 23 Episode 1 451,485 3 Eastenders 24/06/2016 295,061 Eastenders 14/06/2016 435,478 The Great British Sewing Bee Series 4 4 145,011 Eastenders 31/05/2016 426,887 Activewear 5 Celebrity Masterchef Series 11 Episode 1 121,993 Eastenders 09/06/2016 424,902 6 Top Gear Series 23 Episode 4 119,397 Eastenders 03/06/2016 415,419 7 Versailles: Episode 4 107,383 Eastenders 02/06/2016 402,052 8 Professor Green: Dangerous Dogs 106,431 Eastenders 17/06/2016 391,289 9 The Musketeers Series 3 Episode 3 103,386 Eastenders 16/06/2016 390,755 10 New Blood: Case 2, Part 1 102,304 Eastenders 30/05/2016 386,901 Only viewing time for audited platforms is included. -

Translation Rights List Fiction

TRANSLATION RIGHTS LIST FICTION London Book Fair 2017 General ......................................................... p.2 Commercial ............................................... p.10 Crime, Mystery & Thriller ............................ p.14 Young Adult ................................................ p.21 Science Fiction & Fantasy ....................... p.22 ANDY HINE Rights Director (for Brazil, Germany, Italy, Poland, Scandinavia, Latin America and the Baltic States) [email protected] KATE HIBBERT Rights Director (for the USA, Spain, Portugal, Far East and the Netherlands) [email protected] SARAH BIRDSEY Rights Manager (for France, Turkey, Arab States, Israel, Greece, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Slovak Republic, Hungary, Romania, Russia, Serbia and Macedonia) [email protected] JOE DOWLEY Rights Assistant [email protected] Little, Brown Book Group Ltd Carmelite House 50 Victoria Embankment London EC4Y 0DZ Tel: +44 020 3122 6209 Rights sold displayed in parentheses indicates that we do not control the rights * Indicates new title since previous Rights list Titles in italics were not published by Little, Brown Book Group GENERAL * CLOSING DOWN by Sally Abbott Contemporary fiction | Hachette Australia | 288pp | April 2017 A glimpse into a world fractured by a financial crisis and global climate change No matter how strange, difficult and absurd the world becomes, some things never change. The importance of home. Of love. Of kindness to strangers. Of memories and dreams. Australia's rural towns and communities are closing down, much of Australia is being sold to overseas interests, states and countries and regions are being realigned worldwide. Town matriarch Granna Adams, her grandson Roberto, the lonely and thoughtful Clare - all try in their own way to hold on to their sense of self, even as the world around them fractures. -

Origins of NZ English

Origins of NZ English There are three basic theories about the origins of New Zealand English, each with minor variants. Although they are usually presented as alternative theories, they are not necessarily incompatible. The theories are: • New Zealand English is a version of 19th century Cockney (lower-class London) speech; • New Zealand English is a version of Australian English; • New Zealand English developed independently from all other varieties from the mixture of accents and dialects that the Anglophone settlers in New Zealand brought with them. New Zealand as Cockney The idea that New Zealand English is Cockney English derives from the perceptions of English people. People not themselves from London hear some of the same pronunciations in New Zealand that they hear from lower-class Londoners. In particular, some of the vowel sounds are similar. So the vowel sound in a word like pat in both lower-class London English and in New Zealand English makes that word sound like pet to other English people. There is a joke in England that sex is what Londoners get their coal in. That is, the London pronunciation of sacks sounds like sex to other English people. The same joke would work with New Zealanders (and also with South Africans and with Australians, until very recently). Similarly, English people from outside London perceive both the London and the New Zealand versions of the word tie to be like their toy. But while there are undoubted similarities between lower-class London English and New Zealand (and South African and Australian) varieties of English, they are by no means identical. -

Marnie: I Was Worried Lus Xc Iv

the FAMOUS Marnie: I was worried LUS XC IV about coming“ out, E E E X E C V I L S U Marnie’s tired but now I feel of feeling empowered anxious The Geordie Shore star s peaks about her bisexuality for the first” time hen you’re on drunk and it just happened. To future with her. I’m still a bit Geordie Shore, me, that was different because it hesitant to have a full-blown nothing is private was just me and her. It wasn’t for relationship with a girl, but I do (least of all your any other reason than I wanted to, think it would be a possibility. actual privates) so it made me think differently. Why are you hesitant? – and since It was a friend – I’ve known her Because of the job I’m in. Everyone Marnie Simpson for about two years. has an opinion. It shouldn’t be Wjoined the show in 2013, we’ve seen So, you guys had sex? like that, and I hate the fact that her get intimate with co-stars That was the first time, yeah. I worry about it. And I’m still very Gaz Beadle and Aaron Chalmers I wouldn’t really class it as much attracted to boys as well. and get engaged to TOWIE sex, but we did things. It was Have you been with any star Ricky Rayment (who she about a year ago. women since then? split with in September 2015). How did you feel about I’ve kissed girls and been We’ve also seen her kiss a few girls, it the next morning? messaging girls, but it’s still including housemate Chloe Ferry, I [always] thought I’d wake quite uncomfortable, because so when she tweeted last month, up and be embarrassed, but I’m in the public eye. -

Clemency Newman Looking Into the Popular Reality Show Geordie Shore

From reality television to the hyperreal: How do the pressures of reality shows such as Geordie Shore cause their characters to change their physical appearance? Clemency Newman Abstract Looking into the popular reality show Geordie Shore, I will undertake research to answer why it is that the women who appear on the show change their physical appearance and what connection this has to their celebrity status. I hope to argue that because the women are considered lower class, they have no other power than their perceived attractiveness and are therefore pressured into trying to achieve a hyperreal body, relating to Baudrillard’s theory of Simulacra and Simulation. Introduction Reality television is big business, with over 300 reality format shows on air in the US alone (Washington Post, 2015) from Idol to Big Brother, they rake in millions of viewers every night and have a significant impact on popular culture. These shows present a concentrated, edited and scandalised version of everyday life, wrapped in the guise of being true to the viewer, only more dramatic. Television has the ability to shape our view of the world and now with the ever pervasive aspects of social media, networks such as Bravo can imprint an everlasting impression of what we consider normal. However, even when know what we are watching is completely unreal, we accept it as ‘reality’ and accept the characters into our lives, until they become overthrown by a younger, prettier and more outrageous model. Geordie Shore is one such television show which presents an exaggerated, hyperbolic version of reality, with the cast members performing ridiculous, violent and carnal acts in front of a worldwide audience and being celebrated in the process. -

LANGUAGE VARIETY in ENGLAND 1 ♦ Language Variety in England

LANGUAGE VARIETY IN ENGLAND 1 ♦ Language Variety in England One thing that is important to very many English people is where they are from. For many of us, whatever happens to us in later life, and however much we move house or travel, the place where we grew up and spent our childhood and adolescence retains a special significance. Of course, this is not true of all of us. More often than in previous generations, families may move around the country, and there are increasing numbers of people who have had a nomadic childhood and are not really ‘from’ anywhere. But for a majority of English people, pride and interest in the area where they grew up is still a reality. The country is full of football supporters whose main concern is for the club of their childhood, even though they may now live hundreds of miles away. Local newspapers criss-cross the country in their thousands on their way to ‘exiles’ who have left their local areas. And at Christmas time the roads and railways are full of people returning to their native heath for the holiday period. Where we are from is thus an important part of our personal identity, and for many of us an important component of this local identity is the way we speak – our accent and dialect. Nearly all of us have regional features in the way we speak English, and are happy that this should be so, although of course there are upper-class people who have regionless accents, as well as people who for some reason wish to conceal their regional origins. -

The (Unsuccessful) Reality Television Make Under: Class, Illegitimate Femininities, and Resistance in Snog, Marry, Avoid

Outskirts Vol. 35, 2016, 1-20 The (unsuccessful) reality television make under: Class, illegitimate femininities, and resistance in Snog, Marry, Avoid Anthea Taylor In postfeminist media culture, young women are now evaluated, regulated and exhorted to recalibrate in new ways, in new forms, especially the reality makeover program. No less seeking the transformation of its subjects, Britain’s ‘make under’ reality television program, Snog, Marry, Avoid, celebrating women’s ‘natural beauty’, focuses upon women whose gendered performance is considered a threat to normative femininity and the class distinctions with which it is intimately bound. In each episode, women are called to account for their physical, sartorial and behavioural crimes. This paper considers how the show attempts to position these young femininities as illegitimate and explores how the make under seeks to operate – often unsuccessfully – as a form of class makeover. Challenging narratives about the success of reality television in policing the bounds of ‘appropriate’ femininity, subjects routinely reject the judgements and sense of shame that the show seeks to instil, offering up – as this paper argues – a form of resistance that at once reinforces and troubles the program’s class-based logics. Introduction In postfeminist media culture, young women are now evaluated, regulated and exhorted to recalibrate in new ways, in new forms, especially the reality makeover program. No less seeking the transformation of its subjects, Britain’s ‘make under’ reality television program, Snog, Marry, Avoid? – featured on BBC3 – completed its sixth and final season in 2013.i Celebrating the virtues of women’s ‘natural beauty’, it focuses upon women whose performance of (a certain type of) femininity is – for a variety of reasons I will explore – figured as deeply problematic, in extreme need of the kind of intervention staged within the show’s narrative framework. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jana Krejčířová Australian English Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph. D. 2016 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph.D. for her patience and valuable advice. I would also like to thank my partner Martin Burian and my family for their support and understanding. Table of Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................... 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 1. AUSTRALIA AND ITS HISTORY ................................................................. 10 1.1. Australia before the arrival of the British .................................................... 11 1.1.1. Aboriginal people .............................................................................. 11 1.1.2. First explorers .................................................................................... 14 1.2. Arrival of the British .................................................................................... 14 1.2.1. Convicts ............................................................................................. 15 1.3. Australia in the -

Gibling-Dan-June-21-Short

DAN GIBLING 39 Deanshanger Road, 1st ASSISTANT DIRECTOR Old Stratford, Milton Keynes, --- Films, TV, Commercials, Promos --- MK19 6AX Mob: 07815 626 004 - Callbox: 01932 592 572 [email protected] COMPANY TITLE DIRECTOR PRODUCER COMMERCIALS (selection) Cylindr Samsung Guy Soulsby Claire Green Rough Cut Playstation Christopher Poole Bertie Peek Kode Media Sky Vegas TVC Guy Soulsby Jen Gelin NM Productions Braun Matt Holyoak Anissa Payne NM Productions Comic Relief Matt Holyoak Anissa Payne Somesuch Samsung ‘Onions' Sam Hibbard Tom Gardner Kode Media Sky Vegas Christmas TVC Guy Soulsby Jen Gelin Twist & Shout Inside Man 3 Corporate Drama Series Jim Sheilds James Hisset Nexus William Hill Mike & Payne Joshephine Gallagher TBWA McVities TVC Tom Clarkson Emma Moxhay Kode Media Sky Vegas TVC Guy Soulsby Anthony Taylor The Edge Heathrow Corporate George Milton Arij Al-Soltan We Are Social Samsung Online Tom Clarkson Jenna Pannaman DAZN 32Red Betting Online Andrew Green Ultan McGlone Leap Productions Video Arts Corporate Jeff Emerson Naomi Symonds MTV TLOTL Promo Dan Sully Rosie Wells Twist & Shout Inside Man 2 Corporate Drama Series Jim Sheilds James Hisset Jack Morton ‘The Loop’ - Branded short film for Scania Jen Sheridan Amyra Bunyard Across Media Swarovski Diamonds Online Mert & Marcus Gloria Bowman Gas & Electric Barclays Online Jon Riche Matt Klemera Friend BBC Wimbledon TVC Wriggles & Robbins Sorcha Bacon Whisper Films Bose Formula 1- Ch4 Idents Jen Sheridan Jamie McIntosh Squint Opera Empire State Building Video Installation Callum -

New Zealand English

New Zealand English Štajner, Renata Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2011 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:005306 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-26 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Preddiplomski studij Engleskog jezika i književnosti i Njemačkog jezika i književnosti Renata Štajner New Zealand English Završni rad Prof. dr. sc. Mario Brdar Osijek, 2011 0 Summary ....................................................................................................................................2 Introduction................................................................................................................................4 1. History and Origin of New Zealand English…………………………………………..5 2. New Zealand English vs. British and American English ………………………….….6 3. New Zealand English vs. Australian English………………………………………….8 4. Distinctive Pronunciation………………………………………………………………9 5. Morphology and Grammar……………………………………………………………11 6. Maori influence……………………………………………………………………….12 6.1.The Maori language……………………………………………………………...12 6.2.Maori Influence on the New Zealand English………………………….………..13 6.3.The -

British Or American English?

Beteckning Department of Humanities and Social Sciences British or American English? - Attitudes, Awareness and Usage among Pupils in a Secondary School Ann-Kristin Alftberg June 2009 C-essay 15 credits English Linguistics English C Examiner: Gabriella Åhmansson, PhD Supervisor: Tore Nilsson, PhD Abstract The aim of this study is to find out which variety of English pupils in secondary school use, British or American English, if they are aware of their usage, and if there are differences between girls and boys. British English is normally the variety taught in school, but influences of American English due to exposure of different media are strong and have consequently a great impact on Swedish pupils. This study took place in a secondary school, and 33 pupils in grade 9 participated in the investigation. They filled in a questionnaire which investigated vocabulary, attitudes and awareness, and read a list of words out loud. The study showed that the pupils tend to use American English more than British English, in both vocabulary and pronunciation, and that all of the pupils mixed American and British features. A majority of the pupils had a higher preference for American English, particularly the boys, who also seemed to be more aware of which variety they use, and in general more aware of the differences between British and American English. Keywords: British English, American English, vocabulary, pronunciation, attitudes 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction .....................................................................................................................