Creative Wealth in the Middle of Nowhere. Karaganda's Struggle For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6. Current Status of the Environment

6. Current Status of the Environment 6.1. Natural Environment 6.1.1. Desertification Kazakhstan has more deserts within its territory than any other Central Asian country, and approximately 66% of the national land is vulnerable to desertification in various degrees. Desertification is expanding under the influence of natural and artificial factors, and some people, called “environmental refugees,” are obliged to leave their settlements due to worsened living environments. In addition, the Government of RK (Republic of Kazakhstan) issued an alarm in the “Environmental Security Concept of the Republic of Kazakhstan 2004-2015” that the crisis of desertification is not only confined to Kazakhstan but could raise problems such as border-crossing emigration caused by the rise of sandstorms as well as the transfer of pollutants to distant locations driven by large air masses. (1) Major factors for desertification Desertification is taking place due to the artificial factors listed below as well as climate, topographic and other natural factors. • Accumulated industrial wastes after extraction of mineral resources and construction of roads, pipelines and other structures • Intensive grazing of livestock (overgrazing) • Lack of farming technology • Regulated runoff to rivers • Destruction of forests 1) Extraction of mineral resources Wastes accumulated after extraction of mineral resources have serious effects on the land. Exploration for oil and natural gas requires vast areas of land reaching as much as 17 million hectares for construction of transportation systems, approximately 10 million hectares of which is reportedly suffering ecosystem degradation. 2) Overgrazing Overgrazing is the abuse of pastures by increasing numbers of livestock. In the grazing lands in mountainous areas for example, the area allocated to each sheep for grazing is 0.5 hectares, compared to the typical grazing space of 2 to 4 hectares per sheep. -

Enterprises and Organizations – Partners of the Faculty

ENTERPRISES AND ORGANIZATIONS – PARTNERS OF THE FACULTY 1. JSC "Agrofirma- Aktyk" 010017, Akmola region, Tselinograd district, village Vozdvizhenka 2. The Committee on Forestry and Hunting 010000, Astana, st. Orynbor, 8, 5 entrance of the Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Kazakhstan 3. The Water Resources Committee 010000, Astana, Valikhanov Street, Building 43 4. RSE "Phytosanitary" the Ministry of 010000, Astana, Pushkin Street 166 Agriculture 5. LLP "SMCCC (center of Science and 010000, Akmola region, Shortandy District, Nauchnyi manufacture of Crop cultivation) named village, Kirov Street 58 after A.I. Barayev" 6. Republican Scientific methodical center 010000, Akmola region, Shortandy District, Nauchnyi of agrochemical service of the Ministry village, Kirov Street 58 of Agriculture 7. State Republican Centre for 010000, Astana, st. Orynbor, 8, 5 entrance phytosanitary diagnostics and forecasts the Ministry of Agriculture 8. RSE "Zhasyl Aimak" 010000, Astana, Tereshkova street 22/1 9. State Institution "Training and 010000, Akmola region, Sandyktau District, the village Production Sandyktau forestry" of Hutorok 10. LLP "Farmer 2002" 010000, Akmola region, Astrakhan district 11. "Astana Zelenstroy" 010000, Astana, Industrial Zone, 1 12. ASU to protect forests and wildlife 010000, Akmola region, Akkol district, Forestry village "Akkol" 13. State Scientific and Production Center 010000, Astana, Zheltoksan street, 25 of Land Management," the Ministry of Agriculture 14. State Institution "Burabay" 021708, Akmola region, Burabay village, Kenesary str., 45 15. "Kazakh Scientific and Research 021700, Akmola region, Burabay district, Schuchinsk Institute of Forestry" city, Kirov st., 58 16. LLP "Kazakh Research Institute of Soil 050060, Almaty, Al-Farabi Avenue 75в Science and Agrochemistry named after U.Uspanova" 17. -

Messages from Space Explorers to Future Generations

Messages from Space Explorers to future generations start Messages from Space Explorers to future generations by by by year name country intro Messages from Space Explorers to future generations In honour of the fiftieth anniversary To pay tribute to the extraordinary journey of the of human space flight, the United Nations men and women who have flown into space, and to capture their unique perspectives and declared 12 April as the International Day experiences in a distinctive collection, of Human Space Flight. the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), is inviting past and present space explorers to sign an autograph sheet and to provide a message that might inspire future generations. This autograph album contains a copy of the signed sheets received from participating space explorers. The album also contains a copy of the autographs of Yuri Gagarin and Edward H. White on their visit to the United Nations. by by by year name country Messages from Space Explorers to future generations 1961 [ Yuri GAGARIN ] 1965 [ Edward H. WHITE II ] 1972 [ Charlie DUKE ] 1976 [ Vladimir Viktorovich AKSENOV ] 1978 [ Miroslaw HERMASZEWSKI ] 1979 [ Georgi Ivanov IVANOV ] 1980 [ Vladimir Viktorovich AKSENOV ] 1981 [ Jugderdemid GURRAGCHAA • Dumitru-Dorin PRUNARIU ] 1983 [ John FABIAN • Ulf MERBOLD ] 1984 [ Charles David WALKER ] 1985 [ Loren W. ACTON • Sultan Salman ALSAUD • Patrick BAUDRY • Bonnie J. DUNBAR • John FABIAN • Charles David WALKER ] 1988 [ Aleksandar Panayotov ALEKSANDROV ] 1989 [ Richard N. RICHARDS ] 1990 [ Bonnie J. DUNBAR Richard N. RICHARDS ] 1991 [ Ken REIGHTLER • Toktar AUBAKIROV • Helen SHARMAN • Franz VIEHBÖCK • James Shelton VOSS ] 1992 [ Bonnie J. DUNBAR • Ulf MERBOLD • Richard N. RICHARDS James Shelton VOSS ] 1994 [ Ulf MERBOLD • Ken REIGHTLER • Richard N. -

Koktaszhal Porphyritic Copper Mine Development, Kazakhstan

«Алтай Полиметаллы» Altay Polimetally LLC ЖШС Kazakhstan 050000, 050000, Алматы Almaty, Al-farabi қаласы, Аль-Фараби даңғылы, Avenue 95 үй, 64 офис, 95 Office 64, тел. (7273)154-652 Tel. (7273)154-652 Koktaszhal Porphyritic Copper Mine Development, Kazakhstan STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT PLAN Revision 2. November 2014 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 1 2 PROJECT SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................1 3 STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT REQUIREMENTS FOR THE PROJECT ...................................... 2 4 SUMMARY OF STAKEHOLDERS ENGAGEMENT ACTIVITIES CARRIED OUT BY THE COMPANY TO DATE ........................................................................................................................3 5 STAKEHOLDER IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS ........................................................................ 3 5.1 Regulatory Authorities ................................................................................................................ 5 5.2 Companies - Suppliers of Goods and Services .......................................................................... 5 5.3 Suppliers Personnel ................................................................................................................... 5 5.4 Local Population .........................................................................................................................5 -

Country's GDP Grows Slightly in First Half of 2016 Kazakh Senate Chair

+23° / +16°C WEDNESDAY, JULY 27, 2016 No 14 (104) www.astanatimes.com Astana Motorsports Team Performs Well Country’s GDP at Silk Way Rally 2016, Wins T2 Class Grows Slightly in By Anuar Abdrakhmanov First Half of 2016 ASTANA – The four crews of investment growth, 12.8 percent, the Astana Presidential Professional By Zhanna Shayakhmetova Sports Club successfully completed was observed in agriculture, with investment in real estate transac- the Silk Way Rally 2016. The rally, ASTANA – Kazakhstan’s which took place July 8-24 after a tions growing by 5.4 percent, re- economy is still growing due to ported the Prime Minister’s press two-year hiatus, saw riders cover a timely anti-crisis measures taken total of more than 10,000 kilome- service. by the government and the Na- tres in 15 legs between Moscow and Bishimbayev stressed that posi- tional Bank, according to Minister Beijing and through the territory of tive growth rates in short-term of National Economy Kuandyk Russia, Kazakhstan and China. economic indicators can be seen in Bishimbayev. From January to A Kazakh crew of Denis Be- six basic sectors of the economy: June 2016, gross domestic prod- rezovskiy and his co-pilot Ignat industry, agriculture, construction, Falkov, riding a Toyota Land uct grew by 0.1 percent compared trade, transport and communica- Cruiser Prado 200 won in the T2 with the corresponding period in tion. class, which featured cross-coun- 2015, he announced during a gov- Kazakhstan’s international re- serves totalled $96.2 billion on try series production vehicles. ernmental meeting dedicated to the July 1, 2016, and have increased They managed to snatch the victo- socio-economic development of 5.2 percent this year. -

Metallogeny of Northern, Central and Eastern Asia

METALLOGENY OF NORTHERN, CENTRAL AND EASTERN ASIA Explanatory Note to the Metallogenic map of Northern–Central–Eastern Asia and Adjacent Areas at scale 1:2,500,000 VSEGEI Printing House St. Petersburg • 2017 Abstract Explanatory Notes for the “1:2.5 M Metallogenic Map of Northern, Central, and Eastern Asia” show results of long-term joint research of national geological institutions of Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and the Republic of Korea. The latest published geological materials and results of discussions for Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and North Korea were used as well. Described metallogenic objects: 7,081 mineral deposits, 1,200 ore knots, 650 ore regions and ore zones, 231 metallogenic areas and metallogenic zones, 88 metallogenic provinces. The total area of the map is 30 M km2. Tab. 10, fig. 15, list of ref. 94 items. Editors-in-Chief: O.V. Petrov, A.F. Morozov, E.A. Kiselev, S.P. Shokalsky (Russia), Dong Shuwen (China), O. Chuluun, O. Tomurtogoo (Mongolia), B.S. Uzhkenov, M.A. Sayduakasov (Kazakhstan), Hwang Jae Ha, Kim Bok Chul (Korea) Authors G.A. Shatkov, O.V. Petrov, E.M. Pinsky, N.S. Solovyev, V.P. Feoktistov, V.V. Shatov, L.D. Rucheykova, V.A. Gushchina, A.N. Gureev (Russia); Chen Tingyu, Geng Shufang, Dong Shuwen, Chen Binwei, Huang Dianhao, Song Tianrui, Sheng Jifu, Zhu Guanxiang, Sun Guiying, Yan Keming, Min Longrui, Jin Ruogu, Liu Ping, Fan Benxian, Ju Yuanjing, Wang Zhenyang, Han Kunying, Wang Liya (China); Dezhidmaa G., Tomurtogoo O. (Mongolia); Bok Chul Kim, Hwang Jae Ha (Republic of Korea); B.S. Uzhkenov, A.L. -

1 Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan Kostanay State Pedagogical University M. BEKMAGAMBETOVA MODERN

Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan Kostanay State Pedagogical University M. BEKMAGAMBETOVA MODERN HISTORY OF KAZAKHSTAN Kostanay, 2018 1 UDC 94(574) LBC 63.3 (5 Kaz) В39 Considered and recommended for publication at the meeting of the Academic Council of the Kostanay State Pedagogical University Author: M.Bekmagambetova, PhD in Historical Sciences Reviewers: Alexander S. Morrison, Fellou & Tutor in History, New College, Oxford A.Aitmukhambetov, Grand PhD in Historical Sciences, Associate Professor of Kostanay State University named after A. Baytursynov E. Abil, Grand PhD in Historical Sciences, Associate Professor of Kostanay State Pedagogical University Bekmagambetova M. B 39 Modern History of Kazakhstan / Kostanay: Kostanay State Pedagogical University, 2018.- 189 p. ISBN 978-601-7934-58-3 The course of lectures is devoted to the most important period of domestic history. The process of formation of socio-economic, political and spiritual bases of modern Kazakhstan is considered. It is designed for students, undergraduates, all interested in the history of the Republic of Kazakhstan. UDC 94(574) LBC 63.3 (5 Kaz) В39 © Kostanay State Pedagogical University, 2018 2 Contents Course introduction……………………………………………………………..4 Unit I. Introduction to the history of Kazakhstan Topic: The subject and the object of modern history of Kazakhstan. Historiography of the modern history of Kazakhstan………………………………...7 Topic: Historical time and periodization of the history of Kazakhstan. Methodology of historical science…………………………………………………...12 -

Part 2 Almaz, Salyut, And

Part 2 Almaz/Salyut/Mir largely concerned with assembly in 12, 1964, Chelomei called upon his Part 2 Earth orbit of a vehicle for circumlu- staff to develop a military station for Almaz, Salyut, nar flight, but also described a small two to three cosmonauts, with a station made up of independently design life of 1 to 2 years. They and Mir launched modules. Three cosmo- designed an integrated system: a nauts were to reach the station single-launch space station dubbed aboard a manned transport spacecraft Almaz (“diamond”) and a Transport called Siber (or Sever) (“north”), Logistics Spacecraft (Russian 2.1 Overview shown in figure 2-2. They would acronym TKS) for reaching it (see live in a habitation module and section 3.3). Chelomei’s three-stage Figure 2-1 is a space station family observe Earth from a “science- Proton booster would launch them tree depicting the evolutionary package” module. Korolev’s Vostok both. Almaz was to be equipped relationships described in this rocket (a converted ICBM) was with a crew capsule, radar remote- section. tapped to launch both Siber and the sensing apparatus for imaging the station modules. In 1965, Korolev Earth’s surface, cameras, two reentry 2.1.1 Early Concepts (1903, proposed a 90-ton space station to be capsules for returning data to Earth, 1962) launched by the N-1 rocket. It was and an antiaircraft cannon to defend to have had a docking module with against American attack.5 An ports for four Soyuz spacecraft.2, 3 interdepartmental commission The space station concept is very old approved the system in 1967. -

Ecological Problems of Modern Central Kazakhstan: Challenges and Possible Solutions

E3S Web of Conferences 157, 03018 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202015703018 KTTI-2019 Ecological problems of modern central Kazakhstan: challenges and possible solutions Тurgai Alimbaev1, Zhanna Mazhitova2,*, Bibizhamal Omarova2, Bekzhan Kamzayev2, and Kuralai Atanakova³ 1Buketov Karaganda State University, City University, 28, Karaganda, Republic of Kazakhstan 2Astana Medical University, Mira Street, 49a, Nur Sultan, Republic of Kazakhstan ³National University of Arts, Avenue Tauelsіzdіk, 50, Nur Sultan, Republic of Kazakhstan Abstract. This article discusses issues related to the environmental problems in various sectors of the Central Kazakhstan’s economy at the present stage. It is emphasized that the level of environmental pollution is increasing along with industrial progress in coal, non-ferrous and ferrous metallurgy, chemistry, engineering, and the growth of the transport highways network and numerous communications. The authors of the article give examples of how the transition to market mechanisms of economic development generated, on the one hand, the growth of the republic’s powerful economic potential. On the other hand, the increase in industrial production with energy and resource-intensive production has led to a real threat of an environmental crisis in the region. It is concluded that the solution of the environmental problem is possible by preserving and restoring natural systems, a complete social transition to sustainable development by practical implementation of the environmental concept, including natural-resource, techno-economic, demographic and sociocultural aspects. According to the authors, these measures will contribute to the way out of the current environmental crisis, a radical improvement of the environment, will be the key to preserving the ecology of space. -

Expedition 11

EXPEDITION 11: Opening the Door for Return to Flight WWW.SHUTTLEPRESSKIT.COM Updated April 4, 2004 Expedition 11 Press Kit National Aeronautics and Space Administration Table of Contents Mission Overview .................................................................................................... 1 Crew .......................................................................................................................... 5 Mission Objectives ................................................................................................ 10 Spacewalks ............................................................................................................ 19 Russian Soyuz TMA................................................................................................ 20 Science Overview ................................................................................................... 42 Payload Operations Center.................................................................................... 47 Russian Experiments ............................................................................................ 50 U.S. Experiments .................................................................................................... 58 Italian Soyuz Mission Eneide................................................................................... 92 Media Assistance.................................................................................................. 111 Media Contacts .................................................................................................... -

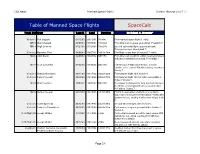

Table of Manned Space Flights Spacecalc

CBS News Manned Space Flights Current through STS-117 Table of Manned Space Flights SpaceCalc Total: 260 Crew Launch Land Duration By Robert A. Braeunig* Vostok 1 Yuri Gagarin 04/12/61 04/12/61 1h:48m First manned space flight (1 orbit). MR 3 Alan Shepard 05/05/61 05/05/61 15m:22s First American in space (suborbital). Freedom 7. MR 4 Virgil Grissom 07/21/61 07/21/61 15m:37s Second suborbital flight; spacecraft sank, Grissom rescued. Liberty Bell 7. Vostok 2 Guerman Titov 08/06/61 08/07/61 1d:01h:18m First flight longer than 24 hours (17 orbits). MA 6 John Glenn 02/20/62 02/20/62 04h:55m First American in orbit (3 orbits); telemetry falsely indicated heatshield unlatched. Friendship 7. MA 7 Scott Carpenter 05/24/62 05/24/62 04h:56m Initiated space flight experiments; manual retrofire error caused 250 mile landing overshoot. Aurora 7. Vostok 3 Andrian Nikolayev 08/11/62 08/15/62 3d:22h:22m First twinned flight, with Vostok 4. Vostok 4 Pavel Popovich 08/12/62 08/15/62 2d:22h:57m First twinned flight. On first orbit came within 3 miles of Vostok 3. MA 8 Walter Schirra 10/03/62 10/03/62 09h:13m Developed techniques for long duration missions (6 orbits); closest splashdown to target to date (4.5 miles). Sigma 7. MA 9 Gordon Cooper 05/15/63 05/16/63 1d:10h:20m First U.S. evaluation of effects of one day in space (22 orbits); performed manual reentry after systems failure, landing 4 miles from target. -

Association of Space Explorers 10Th Planetary Congress Moscow/Lake Baikal, Russia 1994

Association of Space Explorers 10th Planetary Congress Moscow/Lake Baikal, Russia 1994 Commemorative Poster Signature Key Loren Acton Viktor Afanasyev Toyohiro Akiyama STS 51F Soyuz TM-11 Soyuz TM-11 Vladimir Aksyonov Sultan bin Salman al-Saud Buzz Aldrin Soyuz 22, Soyuz T-2 STS 51G Gemini 12, Apollo 11 Alexander Alexandrov Anatoli Artsebarsky Oleg Atkov Soyuz T-9, Soyuz TM-3 Soyuz TM-12 Soyuz T-10 Toktar Aubakirov Alexander Balandin Georgi Beregovoi Soyuz TM-13 Soyuz TM-9 Soyuz 3 Anatoli Berezovoi Karol Bobko Roberta Bondar Soyuz T-5 STS 6, STS 51D, STS 51J STS 42 Scott Carpenter John Creighton Vladimir Dzhanibekov Mercury 7 STS 51G, STS 36, STS 48 Soyuz 27, Soyuz 39, Soyuz T-6 Soyuz T-12, Soyuz T-13 John Fabian Mohammed Faris Bertalan Farkas STS 7, STS 41G Soyuz TM-3 Soyuz 36 Anatoli Filipchenko Dirk Frimout Owen Garriott Soyuz 7, Soyuz 16 STS 45 Skylab III, STS 9 Yuri Glazkov Georgi Grechko Alexei Gubarev Soyuz 24 Soyuz 17, Soyuz 26 Soyuz 17, Soyuz 28 Soyuz T-14 Miroslaw Hermaszewski Alexander Ivanchenkov Alexander Kaleri Soyuz 30 Soyuz 29, Soyuz T-6 Soyuz TM-14 Yevgeni Khrunov Pyotr Klimuk Vladimir Kovolyonok Soyuz 5 Soyuz 13, Soyuz 18, Soyuz 30 Soyuz 25, Soyuz 29, Soyuz T-4 Valeri Kubasov Alexei Leonov Byron Lichtenberg Soyuz 6, Apollo-Soyuz Voskhod 2, Apollo-Soyuz STS 9, STS 45 Soyuz 36 Don Lind Jack Lousma Vladimir Lyakhov STS 51B Skylab III, STS 3 Soyuz 32, Soyuz T-9 Soyuz TM-6 Oleg Makarov Gennadi Manakov Jon McBride Soyuz 12, Soyuz 27, Soyuz T-3 Soyuz TM-10, Soyuz TM-16 STS 41G Ulf Merbold Mamoru Mohri Donald Peterson STS 9,