In Our Own Image: the Child, Canadian Culture, and Our Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Air Cadet League of Canada (Manitoba) Inc

The Air Cadet League of Canada (Manitoba) Inc. NEWSLETTER October 2014 Supporting the Youth of Manitoba since 1941 3/2014 A MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR TO THE MANITOBA AIR CADET COMMUNITY “I would like to take this opportunity to introduce my- meaningful programme for years to come, one that self as your new Chair of the Air Cadet League of Can- they will look back on as helping to shape and make ada in Manitoba. My name is Doug McLennan, and I possible their future goals and aspirations. have served on the League Board of Directors for five Thank you for the privilege of becoming your League years, first as the Aviation Committee Chair, then as Chair for the next year.” Vice Chair for the past three years, and now as the League Chair. My goal for the next year is to further the Air Cadet MEMBERSHIP RESTRUCTURE movement and programme in Manitoba, and by exten- sion across Canada, and to ensure that the support The 2014 Annual General Meeting of the Corporation the League provides to our Squadrons, Squadron held on October 19, 2014 approved the Eighth Sponsoring Committees, and to the over 1340 Cadets amendment to the Corporation’s by-laws which re- in the province remains the best we can give. We structured the membership to a more practicable need to “keep up with the times” so that the pro- structure for our program at this time. There now gramme remains desirable, relevant and sustainable shall be five classes of members in the Corporation as for many years to come. -

Children's Folk Music in Canada: Histories, Performers and Canons

Children’s Folk Music in Canada: Histories, Performers and Canons ANNA HOEFNAGELS Abstract: In this paper the author explores the origins, growth and popularity of prominent children’s performers and their repertoires in English Canada from the 1960s-1980s, arguing that this period saw the formation of a canon of children’s folk music in Canada.Various factors that have supported the creation of a children’s folk music canon are highlighted, including the role of folk song collectors, folk singers, educational institutions, media outlets and the role of parents in the perpetuation of a particular canon of folk songs for children. ike many adults, I was rather uninterested in children’s music until I be- Lcame a parent. However, since the birth of my children, my family has been listening to and watching various performers who specialize in music for children. I am not unique in my piqued interest in this repertoire after the birth of my children; indeed many parents seek to provide a musical environ- ment for their children at home, both through songs and lullabies they may sing to their children, and by listening to commercial recordings made for young children. Early music educators recognize the importance of music in the development of young children, and the particular role that parents can have on their child’s musical development; as researchers Wendy L. Sims and Dneya B. Udtaisuk assert: Early childhood music educators stress the importance of pro- viding rich musical environments for young children. The intro- duction to MENC’s National Standards states, “The years before children enter kindergarten are critical for their musical develop- ment,” and infants and toddlers “should experience music daily while receiving caring, physical contact” (Music Educators Na- Hoefnagels: Children’s Folk Music in Canada 15 tional Conference, 1994). -

KALEIDOSPORT to KRAZY HOUSE

KALEIDOSPORT to KRAZY HOUSE Kaleidosport Sat 4:00-5:00 p.m., 18 Feb-29 Apr 1967 Sat 2:00-4:00 p.m., 6 May-15 Jul 1967 Sat 2:00-4:00 p.m., 9 Dec 1967-7 Sep 1968 Sat 2:00-4:00 p.m., 4 Jan-29 Jun 1969 Sun 2:30-4:00 p.m., 29 Jun-14 Sep 1969 Sat 3:00-4:00 p.m., 10 Jan-2 May 1970 Sun 2:30-4:00 p.m., 5 Apr-13 Sep 1970 Sat 4:00-5:00 p.m., 9 Jan-11 Apr 1971 Sun 2:30-4:00 p.m., 25 Apr-12 Sep 1971 Sun 2:30-4:00 p.m., 2 Jul-3 Sep 1972 A CBC Sports presentation, produced by Don Brown, Kaleidosport provided coverage of a wide variety of athletic events, from highlights of the Canadian Winter Games, which opened the broadcast in February 1967, to harness racing at Greenwood Race Track in Toronto. Most programs would include features on more than one event. The show's host was Lloyd Robertson. Keep Canada Singing Sun 10:00-10:30 p.m., 5 Jun-12 Jun 1955 On two consecutive Sunday nights, for thirty mintes each, the CBC presented the proceedings of the S.P.E.B.S.Q.S.A. (Society for the Preservation and Encouragement of Barber Shop Quartet Singing in America) from the Queen Mary Veterans' Hospital in Montreal. The host was Johnny Rice and the musical director Harry Fraser. Keynotes Sun 1:00-1:15 p.m., 5 Jan 1964 Sun 3:00-3:15 p.m., 5 Apr-28 Jun 1964 Sat 6:30-6:45 p.m., 4 Jul-27 Sep 1964 Keynotes, a quarter-hour musical variety program from Edmonton, featured show tunes and standards sung by Buddy Victor or Dorothy Harpell, who appeared on alternating weeks, backed by Tommy Banks on piano and Harry Boon on organ. -

Celebrating 60 Years: the ACTRA STORY This Special Issue Of

SPECIAL 60TH EDITION 01 C Celebrating 60 years: THE ACTRA STORY This special issue of InterACTRA celebrates ACTRA’s 60th Anniversary – 60 years of great performances, 60 years of fighting for Canadian culture, 4.67 and 60 years of advances in protecting performers. From a handful of brave and determined $ 0256698 58036 radio performers in the ‘40s to a strong 21,000-member union today, this is our story. ALLIANCE ATLANTIS PROUDLY CONGRATULATES ON 60 YEARS OF AWARD-WINNING PERFORMANCES “Alliance Atlantis” and the stylized “A” design are trademarks of Alliance Atlantis Communications Inc.AllAtlantis Communications Alliance Rights Reserved. trademarks of “A” design are Atlantis” and the stylized “Alliance 1943-2003 • actra • celebrating 60 years 1 Celebrating 60 years of working together to protect and promote Canadian talent 401-366 Adelaide St.W., Toronto, ON M5V 1R9 Ph: 416.979.7907 / 1.800.567.9974 • F: 416.979.9273 E: [email protected] • W: www.wgc.ca 2 celebrating 60 years • actra • 1943-2003 SPECIAL 60th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 2003 VOLUME 9, ISSUE 3 InterACTRA is the official publication of ACTRA (Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists), a Canadian union of performers affiliated to the Canadian Labour Congress and the International Federation of Actors. ACTRA is a member of CALM (Canadian Association of Labour Media). InterACTRA is free of charge to all ACTRA Members. EDITOR: Dan MacDonald EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE: Thor Bishopric, Stephen Waddell, Brian Gromoff, David Macniven, Kim Hume, Joanne Deer CONTRIBUTERS: Steve -

News Service

MANIT BA INFORMATION SERVICES BRANCH ROOM 29, LEGISLATIVE BUILDING NEWS WINNIPEG, MANITOBA R3C 0V8 PHONE: (204) 944-3746 COME: February 10, 1984 SERVICE SPONSORSHIP GRANTS AID PUBLIC EVENTS Culture, Heritage and Recreation Minister Eugene Kostyra has announced that 12 project grants totalling $13,844 have been awarded to community groups under the Public Events Sponsorship Program. The program provides assistance to Manitoba non-profit, community-based organizations sponsoring public arts, cultural or heritage events, including exhibitions, performances, readings or lectures. In awarding grants, priority is given to events sponsored by organizations located outside the City of Winnipeg and which feature Manitoba residents or productions. Grants were awarded to: COMMUNITY ORGANIZATION AND PERFORMANCE AMOUNT Altona Southern Manitoba Concerts Inc. - Sarasota Plato Inc. $ 500 Brandon Brandon Allied Arts Council - (Theatre Sans 2,000 Fils $500, Sharon, Lois & Bram $500, Royal Winnipeg Ballet $1,000) School of Music, Brandon University - Coop/ 500 Dodington/Robbin Trio Dominion City Dominion City Moms' Club - Fred Penner 125 Glenboro Glenwawa Recreation District - Actor's Showcase 255 Leaf Rapids Leaf Rapids National Exhibition Centre - 1,687 (Elias Schritt & Bell $642, Theatre Sans Fils $1,045) Lynn Lake Lynn Lake Cultural Council - (Elias Schritt & 2,600 Bell $700, Theatre Sans Fils $1,900) Minnedosa Rolling River Festival of the Arts - Westman 142 Youth Choir Ste. Rose Comite Culturel de Ste. Rose du Lac - Le Cercle - 1,800 Mbliere Selkirk Gordon Howard Senior's Centre - Actor's Showcase 230 Swan River Swan Valley Arts Council - Contemporary 2,100 Dancers $1,300, Theatre Sans Fils $800) Winnipeg Manitoba Crafts Council - Juried Art Show 1,905 -more- -2- SPONSORSHIP GRANTS The Public Events Sponsorship Program was introduced in April 1983, as an expansion of the department's Tour Hosting Program. -

A RICH HISTORY Celebrating 50 Years of Growing Leaders

SPRING 2017 A RICH HISTORY Celebrating 50 Years of Growing Leaders THE UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG MAGAZINE 12. 18. 24. History A Living Through Repeating Test Tube the Years ECONOMIC BRIDGE- BUILDER Jamie is a visionary of Cree descent who is passionate about building bridges between First Nations and business communities, as a pathway to a strong economic and prosperous future for all. With a background as an educator, an elite military Ranger, and as Manitoba’s Treaty Commissioner, he is uniquely positioned to lead the province’s economic portfolio as the Deputy Minister of Growth, Enterprise and Trade. JAMIE WILSON Bridge-builder / Alumnus —– UWINNIPEG.CA/IMPACT THE UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG MAGAZINE SPRING 2017 CONTENTS FEATURE It’s been 50 years since The University of Winnipeg received its charter, and the institution is celebrating its rich history of academic excellence, community, and growing leaders who make an impact on the world around them. Enjoy this commemorative issue, which highlights some of the milestones, memories, events, and people that have shaped the institution over time. 12. 28. History Repeating From the Archives 18. 14. 31. A Living Test Tube Impact 50 By the Numbers 24. 32. Through the Years A Long Tradition of Fine Art Appreciation 26. 50 Years of Classic Competition UWINNIPEG MAGAZINE EDITORS We hope you enjoy this issue of UWinnipeg Helen Cholakis magazine. Produced twice annually, The University Kevin Rosen NEWSWORTHY 2 of Winnipeg’s revamped flagship publication contains recent news, initiatives, and successes -

The Child, Canadian Culture and Our Future

Carole Henderson Carpenter THE JOHN P. ROBARTS PROFESSOR OF CANADIAN STUDIES NINTH ANNUAL ROBARTS LECTURE 29 March 1995 York University, Toronto, Ontario Professor Carole Henderson Carpenter is one of the leading folklorists in Canada. She has been with York's Division of Humanities since 1971 and teaches courses in Canadian Culture, Folklore and Culture, and the Culture of Childhood. Dr. Carpenter was instrumental in establishing the Folklore Studies Association of Canada (1975). She also organized the Ontario Folklore Centre (1987) and its collection, the Ontario Folklore- Folklife Archive, of which she is the Director. In recent years, she has been active in public folklore work within the Ontario heritage community; and completed the province's first-ever-intangible heritage conservation strategy on Muskoka. Professor Carpenter's numerous publications include three major resources on Canadian folklore: Many Voices: a Study of Folklore Activities in Canada and Their Role in Canadian Culture; A Bibliography of Canadian Folklore in English (with Edith Fowke); and Explorations in Canadian Folklore. She is currently completing a book on children's own culture, Small Fry: Childhood in Canada, and a study of a form of women's writing related to tradition, Recipes for Living. In her Robarts Lecture, Professor Carpenter explores the cultural status of children in Canada, the relationship of their marginalization to our contemporary identity, and the implications for our cultural future. In Our Own Image: The Child, Canadian Culture And Our Future For my Children Introduction The following lecture was first delivered as I entered the last quarter of my tenure in the Robarts Chair of Canadian Studies at York University. -

Andrew Clark: Number One, I Want to Call Attention to a Book I Read a While Ago That I Thought Was Tremendous

Andrew Clark: Number one, I want to call attention to a book I read a while ago that I thought was tremendous. The author is sitting beside me. It’s Air Farce: 40 Years of Flying By the Seat of Our Pants. As someone who writes about the history of comedy, I wish he’d written this a little bit before my book, because then I could’ve just used it as a secondary source. It’s a tremendous book. It’s a really, really funny, well-written book, and it’s going to be valuable for people who study comedy for years and years to come, so on their behalf, I thank you, Don Ferguson… Don Ferguson: You’re welcome. AC: And I welcome you once again to Humber College Comedy Primetime. (applause) And I have to say, I got to learn a few things about you that I didn’t know, particularly, and I mentioned it earlier, that you didn’t have a very direct route into comedy. There was no comedy school. I think you were always being funny one way or another, but can you talk a little bit about your early days in Montreal, at Loyola, and your march through the counterculture of the sixties, to a degree? DF: (laughs) Well, I’m obviously a baby boomer, and I came of age, I guess in a way, in the sixties. Now I’m in my sixties. Funny, isn’t it? At the time when I was in school, high school and then university, there were no comedy clubs of any kind anywhere. -

Music of Victor Davies Concert Works

1 MUSIC OF VICTOR DAVIES CONCERT WORKS ORCHESTRAL “Jazz Piano Concerto“ (Piano Concerto No. 2) (2001) 25:00 * Theme with Nine Scenes ( A Detective Story) 17:00. Sorbet (A Waltz) 5:00, Farewell 6:00 * Commissioned by the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra and the Canada Council for Conductor/ Pianist Bramwell Tovey to play and conduct on the occasion of his Final Gala Concert with the WSO commemorating his 12 successful years as Musical Direstor of the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra * Premiere May 13, 2001 Bramwell Tovey- piano-conductor - Winnipeg symphony Orchestra * solo acoustic piano, 22222 /4331 /Timp /Perc 2/ Strgs “Jazz Concerto For Organ & Orchestra” (The St. Andrew's-Wesley Concerto) (2000) 25:00 * Boogie Pipes 6:00, Blue Pipes 4:30, Cool Pipes 4:10, 4. Hot Pipes (Ragging the Pipes!) 6:00 * Commissioned by Calgary International Organ Foundation, Music Canada 2000 Festival Inc., underwritten by Edwards Charitable Foundation, THE HAMBER FOUNDATION the Canada Council. * Premiere Calgary May 13, 2000 Wayne Marshall - organ - The Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra, Howard Cable Conductor. * Organ, 2222/4331/Timp /Perc 2 /Strgs “Music for The XIII Pan American Games Opening & Closing Ceremonies” (1999) * (Symphonic Marches) - Welcome the Champions 3:07, The Glory of The Games 2:28, North & South On Parade 3:03, The Mosquito March 2:14, Pan Am Fiesta 3:56, I Want To Be A Champion Too 3:21, Canada’s Here! 2:14. The Geese 2:40 2222/4331/Timp /2 /Harp/Strgs (Chorus -The Geese only) * Heart Of the Continent (The Seasons) (a dance/ballet) Autumn Splendour -

Discover Canada with !

index NOTE: The following abbreviations have been used in the index: Fort McMurray, 141 NHS: National Historic Site; NP: National Park; PP: Provincial Park. Fort Whoop-Up (Lethbridge), 128 Glendon, 103 A Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, 16 Aboriginal heritage Kananaskis Country, 115, 147 Annual Veteran’s Feast (Ottawa), 269 Rocky Mountaineer train, 117 Back to Batoche Days (Batoche NHS, SK), 173 St. Paul, 136 Canadian Aboriginal Festival (Hamilton, ON), 283 Taber, 71 Canadian Aboriginal Hand Games Vulcan, 143 Championship (Behchoko, NT), 63 Wood Buffalo National Park, 129 Eskimo Museum (Churchill, MB), 254 André, Saint Brother, 251 Festival de Voyageur (Winnipeg, MB), 50 Arsenault, Édouard, 122 Great Northern Arts Festival (Inuvik, NT), 179 Asian heritage Gwaii Haanas NP (Haida Gwaii, BC), 283 Asian Heritage Month (Richmond, BC), 114 Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump (AB), 16 Chinese New Year, BC, 20–21 Hôtel-Musée Premières Nations (Québec City), 29 Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden National Aboriginal Day (Fort Langley, BC), 144–145 (Vancouver), 20, 270 Nk’Mip Cellars (Osoyoos, BC), 107, 195 Japanese cuisine, Vancouver, 39 Spirit Bear Adventures (Klemtu, BC), 213 Nitobe Memorial Garden (Vancouver), 95 Squamish Lil’wat Cultural Centre (Whistler, BC), 145 Vancouver International Bhangra Celebration Stanley Park (Vancouver), 66, 144 (City of Bhangra), 110 Tofino (Vancouver Island, BC), 61 Toonik Tyme (Iqaluit, NU), 86–87 B Acadian heritage Banff National Park, Alberta, 160, 219. See also Acadian National Holiday (Caraquet, NB), 195 Jasper NP Chéticamp (NS), 242 Baker Creek Bistro, 45 Festival acadien de Clare (Little Brook, NS), 194 Banff/Lake Louise Winter Festival, 24 rappie pie (West Pubnico, NS), 311 Banff Mountain Film and Book Festival, 266 accommodations Banff Springs Golf Course, 181 Algonquin Hotel (St. -

Arts and Learning Environmental Scan

ARTS AND LEARNING ENVIRONMENTAL SCAN Through delivering quality arts education programs which often build partnerships between artists, schools, and other community organizations, artist, teachers, arts organizations and public funders are building healthier communities. ArtsSmarts - Caslan School - AB, 2006 FINAL REPORT Directed by Louise Poulin Jennifer Ginder, Jean Jolicoeur, Cathy Smalley Presented to the Canadian Public Arts Funders (CPAF) and the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Working Group on Arts and Learning August 31, 2006 Table of Contents Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.......................................................................................................................4 1. Purpose ................................................................................................................................................................5 2. Methodology........................................................................................................................................................7 3. Key Findings .....................................................................................................................................................10 3.1 The Current Situation: a highly valued contribution ................................................................................10 3.2 Trends.......................................................................................................................................................14 4. Directions and Actions ......................................................................................................................................20 -

2003 Fall Issue

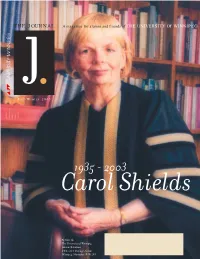

THE JOURNAL A magazine for alumni and friends of THE UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG Fall/Winter 2003 1935 - 2003 Carol Shields Return to: The University of Winnipeg Alumni Relations ??. 4W21-515 Portage Avenue THE JOURNAL Winnipeg, Manitoba R3B 2E9 features. COVER STORY: CAROL SHIELDS, 1935 – 2003 | 4 The University of Winnipeg celebrates the life of our fifth Chancellor BICUSPIDS IN BOLIVIA | 6 The International Adventures of the New Alumni Association President COLLABORATION SOLVES THE SEQUENCE OF SARS | 8 Alumni contribute to vital research BERNICE BLAZEWICZ PITCAIRN | 12 A tradition of generosity comes full circle IN TENSION | 14 Todd Scarth ’00 balances culture and public policy THE GARDEN OF LANGUAGE | 16 Professor Carol Harvey: cultivating a love of French literature IT’S GREAT TO BE HOME | 18 Alumna Susan Thompson leads The University of Winnipeg Foundation content. 6. 8. departments. 14. 16. YOUR LETTERS | 2 EDITOR’S NOTE | 3 VOLUNTEER OPPORTUNITIES | 3 UPDATE U | 7 ALUMNI NEWS BRIEFS | 10 ALUMNI AUTHORS | 13 CLASS ACTS | 20 IN MEMORIAM | 24 Editorial Team: Editor, Lois Cherney ’84; Managing Editor, Annette Elvers ’93; Communications Officer, Kendra Gaede; and THE JOURNAL Director of Communications, Katherine Unruh; | Alumni Council Communications Team: Team Leader, Bryan Oborne ’89; Assistant Team Leader, Jane Dick ’72; Christopher Cottick ’86; Barbara Kelly ’60; Vince Merke ’01; Thamilarasu Subramaniam ’96; and Elizabeth Walker ’98 | Contributing Writers: : Neil Besner, Lois Cherney ’84, Paula Denbow, Annette Cover Elvers ’93, Kendra Gaede, Leslie Malkin, Tina Portman, Paul Samyn ’86, Patti Tweed ’95, Betsy Van der Graaf | Graphic Subject: Carol Shields Design: Guppy | Photography: grajewski.fotograph,Thamilarasu Subramaniam ’96 | Printing: Prolific Group Portrait:The University of The Journal is published in Fall and Spring for the alumni, faculty, staff, and friends of The University of Winnipeg by the Alumni Winnipeg Archives and Communications offices.