Analysis of Aerosol Interactions with Numerical Techniques for Solving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Particle Characterisation In

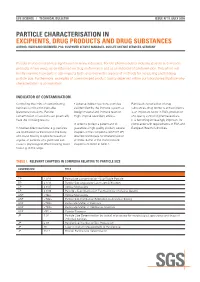

LIFE SCIENCE I TECHNICAL BULLETIN ISSUE N°11 /JULY 2008 PARTICLE CHARACTERISATION IN EXCIPIENTS, DRUG PRODUCTS AND DRUG SUBSTANCES AUTHOR: HILDEGARD BRÜMMER, PhD, CUSTOMER SERVICE MANAGER, SGS LIFE SCIENCE SERVICES, GERMANY Particle characterization has significance in many industries. For the pharmaceutical industry, particle size impacts products in two ways: as an influence on drug performance and as an indicator of contamination. This article will briefly examine how particle size impacts both, and review the arsenal of methods for measuring and tracking particle size. Furthermore, examples of compromised product quality observed within our laboratories illustrate why characterization is so important. INDICATOR OF CONTAMINATION Controlling the limits of contaminating • Adverse indirect reactions: particles Particle characterisation of drug particles is critical for injectable are identified by the immune system as substances, drug products and excipients (parenteral) solutions. Particle foreign material and immune reaction is an important factor in R&D, production contamination of solutions can potentially might impose secondary effects. and quality control of pharmaceuticals. have the following results: It is becoming increasingly important for In order to protect a patient and to compliance with requirements of FDA and • Adverse direct reactions: e.g. particles guarantee a high quality product, several European Health Authorities. are distributed via the blood in the body chapters in the compendia (USP, EP, JP) and cause toxicity to specific tissues or describe techniques for characterisation organs, or particles of a given size can of limits. Some of the most relevant cause a physiological effect blocking blood chapters are listed in Table 1. flow e.g. in the lungs. -

Chapter 3 Bose-Einstein Condensation of an Ideal

Chapter 3 Bose-Einstein Condensation of An Ideal Gas An ideal gas consisting of non-interacting Bose particles is a ¯ctitious system since every realistic Bose gas shows some level of particle-particle interaction. Nevertheless, such a mathematical model provides the simplest example for the realization of Bose-Einstein condensation. This simple model, ¯rst studied by A. Einstein [1], correctly describes important basic properties of actual non-ideal (interacting) Bose gas. In particular, such basic concepts as BEC critical temperature Tc (or critical particle density nc), condensate fraction N0=N and the dimensionality issue will be obtained. 3.1 The ideal Bose gas in the canonical and grand canonical ensemble Suppose an ideal gas of non-interacting particles with ¯xed particle number N is trapped in a box with a volume V and at equilibrium temperature T . We assume a particle system somehow establishes an equilibrium temperature in spite of the absence of interaction. Such a system can be characterized by the thermodynamic partition function of canonical ensemble X Z = e¡¯ER ; (3.1) R where R stands for a macroscopic state of the gas and is uniquely speci¯ed by the occupa- tion number ni of each single particle state i: fn0; n1; ¢ ¢ ¢ ¢ ¢ ¢g. ¯ = 1=kBT is a temperature parameter. Then, the total energy of a macroscopic state R is given by only the kinetic energy: X ER = "ini; (3.2) i where "i is the eigen-energy of the single particle state i and the occupation number ni satis¯es the normalization condition X N = ni: (3.3) i 1 The probability -

2. Classical Gases

2. Classical Gases Our goal in this section is to use the techniques of statistical mechanics to describe the dynamics of the simplest system: a gas. This means a bunch of particles, flying around in a box. Although much of the last section was formulated in the language of quantum mechanics, here we will revert back to classical mechanics. Nonetheless, a recurrent theme will be that the quantum world is never far behind: we’ll see several puzzles, both theoretical and experimental, which can only truly be resolved by turning on ~. 2.1 The Classical Partition Function For most of this section we will work in the canonical ensemble. We start by reformu- lating the idea of a partition function in classical mechanics. We’ll consider a simple system – a single particle of mass m moving in three dimensions in a potential V (~q ). The classical Hamiltonian of the system3 is the sum of kinetic and potential energy, p~ 2 H = + V (~q ) 2m We earlier defined the partition function (1.21) to be the sum over all quantum states of the system. Here we want to do something similar. In classical mechanics, the state of a system is determined by a point in phase space.Wemustspecifyboththeposition and momentum of each of the particles — only then do we have enough information to figure out what the system will do for all times in the future. This motivates the definition of the partition function for a single classical particle as the integration over phase space, 1 3 3 βH(p,q) Z = d qd pe− (2.1) 1 h3 Z The only slightly odd thing is the factor of 1/h3 that sits out front. -

Particle Number Concentrations and Size Distribution in a Polluted Megacity

https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-2020-6 Preprint. Discussion started: 17 February 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. Particle number concentrations and size distribution in a polluted megacity: The Delhi Aerosol Supersite study Shahzad Gani1, Sahil Bhandari2, Kanan Patel2, Sarah Seraj1, Prashant Soni3, Zainab Arub3, Gazala Habib3, Lea Hildebrandt Ruiz2, and Joshua S. Apte1 1Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering, The University of Texas at Austin, Texas, USA 2McKetta Department of Chemical Engineering, The University of Texas at Austin, Texas, USA 3Department of Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, New Delhi, India Correspondence: Joshua S. Apte ([email protected]), Lea Hildebrandt Ruiz ([email protected]) Abstract. The Indian national capital, Delhi, routinely experiences some of the world's highest urban particulate matter concentrations. While fine particulate matter (PM2.5) mass concentrations in Delhi are at least an order of magnitude higher than in many western cities, the particle number (PN) concentrations are not similarly elevated. Here we report on 1.25 years of highly 5 time resolved particle size distributions (PSD) data in the size range of 12–560 nm. We observed that the large number of accumulation mode particles—that constitute most of the PM2.5 mass—also contributed substantially to the PN concentrations. The ultrafine particles (UFP, Dp <100 nm) fraction of PN was higher during the traffic rush hours and for daytimes of warmer seasons—consistent with traffic and nucleation events being major sources of urban UFP. UFP concentrations were found to be relatively lower during periods with some of the highest mass concentrations. -

Statistical Physics 06/07

STATISTICAL PHYSICS 06/07 Quantum Statistical Mechanics Tutorial Sheet 3 The questions that follow on this and succeeding sheets are an integral part of this course. The code beside each question has the following significance: • K: key question – explores core material • R: review question – an invitation to consolidate • C: challenge question – going beyond the basic framework of the course • S: standard question – general fitness training! 3.1 Particle Number Fluctuations for Fermions [s] (a) For a single fermion state in the grand canonical ensemble, show that 2 h(∆nj) i =n ¯j(1 − n¯j) wheren ¯j is the mean occupancy. Hint: You only need to use the exclusion principle not the explict form ofn ¯j. 2 How is the fact that h(∆nj) i is not in general small compared ton ¯j to be reconciled with the sharp values of macroscopic observables? (b) For a gas of noninteracting particles in the grand canonical ensemble, show that 2 X 2 h(∆N) i = h(∆nj) i j (you will need to invoke that nj and nk are uncorrelated in the GCE for j 6= k). Hence show that for noninteracting Fermions Z h(∆N)2i = g() f(1 − f) d follows from (a) where f(, µ) is the F-D distribution and g() is the density of states. (c) Show that for low temperatures f(1 − f) is sharply peaked at = µ, and hence that 2 h∆N i ' kBT g(F ) where F = µ(T = 0) R ∞ ex dx [You may use without proof the result that −∞ (ex+1)2 = 1.] 3.2 Entropy of the Ideal Fermi Gas [C] The Grand Potential for an ideal Fermi is given by X Φ = −kT ln [1 + exp β(µ − j)] j Show that for Fermions X Φ = kT ln(1 − pj) , j where pj = f(j) is the probability of occupation of the state j. -

Appendix a Review of Probability Distribution

Appendix A Review of Probability Distribution In this appendix we review some fundamental concepts of probability theory. After deriving in Sect. A.1 the binomial probability distribution, in Sect. A.2 we show that for systems described by a large number of random variables this distribution tends to a Gaussian function. Finally, in Sect. A.3 we define moments and cumulants of a generic probability distribution, showing how the central limit theorem can be easily derived. A.1 Binomial Distribution Consider an ideal gas at equilibrium, composed of N particles, contained in a box of volume V . Isolating within V a subsystem of volume v, as the gas is macroscop- ically homogeneous, the probability to find a particle within v equals p = v/V , while the probability to find it in a volume V − v is q = 1 − p. Accordingly, the probability to find any one given configuration (i.e. assuming that particles could all be distinguished from each other), with n molecules in v and the remaining (N − n) within (V − v), would be equal to pnqN−n, i.e. the product of the respective prob- abilities.1 However, as the particles are identical to each other, we have to multiply this probability by the Tartaglia pre-factor, that us the number of possibilities of 1Here, we assume that finding a particle within v is not correlated with finding another, which is true in ideal gases, that are composed of point-like molecules. In real fluids, however, since molecules do occupy an effective volume, we should consider an excluded volume effect. -

Aerosol Particle Measurements at Three Stationary Sites in The

Supplementary material to Aerosol particle measurements at three stationary sites in the megacity of Paris during summer 2009: Meteorology and air mass origin dominate aerosol particle composition and size distribution F. Freutel 1, J. Schneider 1, F. Drewnick 1, S.-L. von der Weiden-Reinmüller 1, M. Crippa 2, A. S. H. Prévôt 2, U. Baltensperger 2, L. Poulain 3, A. Wiedensohler 3, J. Sciare 4, R. Sarda- Estève 4, J. F. Burkhart 5, S. Eckhardt 5, A. Stohl 5, V. Gros 4, A. Colomb 6,7 , V. Michoud 6, J. F. Doussin 6, A. Borbon 6, M. Haeffelin 8,9 , Y. Morille 9,10 , M. Beekmann6, S. Borrmann 1,11 [1] Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, Mainz, Germany [2] Paul Scherrer Institute, Villigen, Switzerland [3] Leibniz Institute for Tropospheric Research, Leipzig, Germany [4] Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l'Environnement, Gif-sur-Yvette, France [5] Norwegian Institute for Air Research, Kjeller, Norway [6] LISA, UMR-CNRS 7583, Université Paris Est Créteil (UPEC), Université Paris Diderot (UPD), Créteil, France [7] LaMP, Clermont Université, Université Blaise Pascal, CNRS, Aubière, France [8] Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace, Paris, France [9] Site Instrumental de Recherche par Télédétection Atmosphérique, Palaiseau, France [10] Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique, Palaiseau, France [11] Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Mainz, Germany Correspondence to: J. Schneider ([email protected]) 1 Table S1. Results from the intercomparison measurements between the gas phase and BC measurement instruments -

SP-ICP-MS Analysis of Size and Number Concentration in Mixtures

APPLICATION NOTE ICP – Mass Spectrometry Authors: Ruth C. Merrifield Jamie R. Lead Center for Environmental NanoScience and Risk (CENR), Arnold School of Public Health University of South Carolina, SC Chady Stephan PerkinElmer, Inc. Shelton, CT SP-ICP-MS Analysis of Size and Number Concentration in Mixtures Introduction It is challenging to separate of Monometallic and Bimetallic and measure the physical and chemical properties of (Core-shell) Nanoparticles monometallic and bimetallic engineered nanoparticles (NPs), especially when mixtures of NPs consist of particles of similar size, composition, and especially when present at low concentrations. Fully characterizing suspensions of NPs usually requires a multimethod approach to yield the most reliable results1,2. This process becomes increasingly difficult for more complex bimetallic NPs used in some applications or for those that require a mixture of different NPs, since differentiating between NPs can be a slow and arduous task. There are a variety of techniques that have been used for the determination of particle diameter, composition, and particle number concentration (part. mL-1) of engineered NPs, including dynamic light scattering (DLS), field flow fractionation (FFF), ultraviolet/visible spectroscopy (UV/Vis), multi-angle light scattering (MALS), and, more recently, single particle inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (SP-ICP-MS)3. All these techniques have their own strengths and weaknesses as well as measuring size and/or composition in different ways. Both DLS and FFF measure the particles’ hydrodynamic diameter; Table 1. NexION 350D ICP-MS operating conditions. however, FFF has the advantage of separating particles on the Parameter Value basis of their hydrodynamic size, making it unbiased to particle Nebulizer Meinhard® size, unlike DLS. -

![Arxiv:1805.09819V2 [Cond-Mat.Quant-Gas] 13 Jun 2018 Mained Elusive](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2987/arxiv-1805-09819v2-cond-mat-quant-gas-13-jun-2018-mained-elusive-1012987.webp)

Arxiv:1805.09819V2 [Cond-Mat.Quant-Gas] 13 Jun 2018 Mained Elusive

Probing entanglement in a many-body-localized system Alexander Lukin,1 Matthew Rispoli,1 Robert Schittko,1 M. Eric Tai,1 Adam M. Kaufman,1, 2 Soonwon Choi,1 Vedika Khemani,1 Julian L´eonard,1 and Markus Greiner1, ∗ 1Department of Physics, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA 2JILA, National Institute of Standards and Technology and University of Colorado, and Department of Physics, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado 80309, USA An interacting quantum system that is subject to disorder may cease to thermalize due to lo- calization of its constituents, thereby marking the breakdown of thermodynamics. The key to our understanding of this phenomenon lies in the system's entanglement, which is experimentally chal- lenging to measure. We realize such a many-body-localized system in a disordered Bose-Hubbard chain and characterize its entanglement properties through particle fluctuations and correlations. We observe that the particles become localized, suppressing transport and preventing the ther- malization of subsystems. Notably, we measure the development of non-local correlations, whose evolution is consistent with a logarithmic growth of entanglement entropy - the hallmark of many- body localization. Our work experimentally establishes many-body localization as a qualitatively distinct phenomenon from localization in non-interacting, disordered systems. INTRODUCTION A Number entanglement Configurational entanglement Isolated quantum many-body systems, undergoing uni- tary time evolution, maintain their initial global purity. However, the presence of interactions drives local ther- Subsystem A Subsystem B Subsystem A Subsystem B B malization: the coupling between any subsystem and its Thermal MBL Anderson remainder mimics the contact with a bath. This causes interacting number entanglement disordered the subsystem's degrees of freedom to be ultimately de- configurational entanglement scribed by a thermal ensemble, even if the full system is in a pure state [1{5]. -

Particle Number Concentrations and Size Distribution in a Polluted Megacity: the Delhi Aerosol Supersite Study

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 8533–8549, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-8533-2020 © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Particle number concentrations and size distribution in a polluted megacity: the Delhi Aerosol Supersite study Shahzad Gani1, Sahil Bhandari2, Kanan Patel2, Sarah Seraj1, Prashant Soni3, Zainab Arub3, Gazala Habib3, Lea Hildebrandt Ruiz2, and Joshua S. Apte1 1Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA 2McKetta Department of Chemical Engineering, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA 3Department of Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, New Delhi, India Correspondence: Joshua S. Apte ([email protected]) and Lea Hildebrandt Ruiz ([email protected]) Received: 2 January 2020 – Discussion started: 17 February 2020 Revised: 25 May 2020 – Accepted: 8 June 2020 – Published: 22 July 2020 Abstract. The Indian national capital, Delhi, routinely expe- that a reduction in mass concentration, especially in winter, riences some of the world’s highest urban particulate matter may not produce a proportional reduction in PN concentra- concentrations. While fine particulate matter (PM2:5) mass tions. Strategies that only target accumulation mode particles concentrations in Delhi are at least an order of magnitude (which constitute much of the fine PM2:5 mass) may even higher than in many western cities, the particle number (PN) lead to an increase in the UFP concentrations as the coagula- concentrations are not similarly elevated. Here we report on tion sink decreases. 1.25 years of highly time-resolved particle size distribution (PSD) data in the size range of 12–560 nm. -

Chapter 10 AEROSOLS in MODELS-3 CMAQ Francis S

EPA/600/R-99/030 Chapter 10 AEROSOLS IN MODELS-3 CMAQ Francis S. Binkowski* Atmospheric Modeling Division National Exposure Research Laboratory U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27711 ABSTRACT The aerosol module of the CMAQ is designed to be an efficient and economical depiction of aerosol dynamics in the atmosphere. The approach taken represents the particle size distribution as the superposition of three lognormal subdistributions, called modes. The processes of coagulation, particle growth by the addition of new mass, particle formation, etc. are included. Time stepping is done with analytical solution to the differential equations for the conservation of number and species mass conservation. The module considers both PM2.5 and PM10 and includes estimates of the primary emissions of elemental and organic carbon, dust and other species not further specified. Secondary species considered are sulfate, nitrate, ammonium, water and organic from precursors of anthropogenic and biogenic origin. Extinction of visible light by aerosols represented by two methods, a parametric approximation to Mie extinction and an empirical approach based upon field data. The algorithms describing cloud interactions are also included in this chapter. *On assignment from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. Corresponding author address: Francis S. Binkowski, MD-80, Research Triangle Park, NC 27711. E-mail: [email protected] EPA/600/R-99/030 10.0 THE AEROSOL PORTION OF MODELS-3 CMAQ Inclusion of aerosol particles in an air quality model presents several challenges. Among these are the differences between the physical characteristics of gases and particles. -

Lecture 7: Ensembles

Matthew Schwartz Statistical Mechanics, Spring 2019 Lecture 7: Ensembles 1 Introduction In statistical mechanics, we study the possible microstates of a system. We never know exactly which microstate the system is in. Nor do we care. We are interested only in the behavior of a system based on the possible microstates it could be, that share some macroscopic proporty (like volume V ; energy E, or number of particles N). The possible microstates a system could be in are known as the ensemble of states for a system. There are dierent kinds of ensembles. So far, we have been counting microstates with a xed number of particles N and a xed total energy E. We dened as the total number microstates for a system. That is (E; V ; N) = 1 (1) microstatesk withsaXmeN ;V ;E Then S = kBln is the entropy, and all other thermodynamic quantities follow from S. For an isolated system with N xed and E xed the ensemble is known as the microcanonical 1 @S ensemble. In the microcanonical ensemble, the temperature is a derived quantity, with T = @E . So far, we have only been using the microcanonical ensemble. 1 3 N For example, a gas of identical monatomic particles has (E; V ; N) V NE 2 . From this N! we computed the entropy S = kBln which at large N reduces to the Sackur-Tetrode formula. 1 @S 3 NkB 3 The temperature is T = @E = 2 E so that E = 2 NkBT . Also in the microcanonical ensemble we observed that the number of states for which the energy of one degree of freedom is xed to "i is (E "i) "i/k T (E " ).