Comics As PHILOSOPHY This Page Intentionally Left Blank Comics As PHILOSOPHY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Research Paper

Research Paper TITLE: “Effects of Ben 10 on kids in the age- group 5 to 8 years.” Mrs. Devendar Sandhu Publication Date: 12/07/2014 Educational Technology Research Paper ii Abstract “The problem with our society is that our values aren‟t in the right place. There‟s an awful lot of bleeding and naked bodies on prime-time networks, but not nearly enough cable television on public programming.” ― Bauvard, Evergreens Are Prudish Technology has expanded the availability of information through various routes, such as, television, music, movies, internet and magazines. These routes avail children to endless learning venues about any issue that might be of interest to them. Television is a common media mode which is available to most Indian houses. As per the Turnaround Management Association „s TAM Annual Universe Update - 2010, India now has over 134 million households (out of 223 million) with television sets, of which over 103 million have access to Cable TV or Satellite TV. Kids are exposed to TV at a very young age and they view TV actively or passively without any filtrations, one program after the other. Unless parents are empowered with expert information, they are ill-equipped to judge which programs to place off-limits for their kids. This retrospective descriptive study explores whether kids and their parents felt the side effects of viewing Ben 10. The sample population of 30 kids in the age – group 5 to 8 years old and their parents participated in the research. Factors examined in the study were psychological effects, health effects, TV contents rating views, etc. -

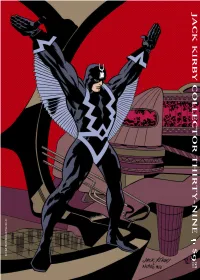

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR THIRTY-NINE $9 95 IN THE US . c n I , s r e t c a r a h C l e v r a M 3 0 0 2 © & M T t l o B k c a l B FAN FAVORITES! THE NEW COPYRIGHTS: Angry Charlie, Batman, Ben Boxer, Big Barda, Darkseid, Dr. Fate, Green Lantern, RETROSPECTIVE . .68 Guardian, Joker, Justice League of America, Kalibak, Kamandi, Lightray, Losers, Manhunter, (the real Silver Surfer—Jack’s, that is) New Gods, Newsboy Legion, OMAC, Orion, Super Powers, Superman, True Divorce, Wonder Woman COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .78 TM & ©2003 DC Comics • 2001 characters, (some very artful letters on #37-38) Ardina, Blastaar, Bucky, Captain America, Dr. Doom, Fantastic Four (Mr. Fantastic, Human #39, FALL 2003 Collector PARTING SHOT . .80 Torch, Thing, Invisible Girl), Frightful Four (Medusa, Wizard, Sandman, Trapster), Galactus, (we’ve got a Thing for you) Gargoyle, hercules, Hulk, Ikaris, Inhumans (Black OPENING SHOT . .2 KIRBY OBSCURA . .21 Bolt, Crystal, Lockjaw, Gorgon, Medusa, Karnak, C Front cover inks: MIKE ALLRED (where the editor lists his favorite things) (Barry Forshaw has more rare Kirby stuff) Triton, Maximus), Iron Man, Leader, Loki, Machine Front cover colors: LAURA ALLRED Man, Nick Fury, Rawhide Kid, Rick Jones, o Sentinels, Sgt. Fury, Shalla Bal, Silver Surfer, Sub- UNDER THE COVERS . .3 GALLERY (GUEST EDITED!) . .22 Back cover inks: P. CRAIG RUSSELL Mariner, Thor, Two-Gun Kid, Tyrannus, Watcher, (Jerry Boyd asks nearly everyone what (congrats Chris Beneke!) Back cover colors: TOM ZIUKO Wyatt Wingfoot, X-Men (Angel, Cyclops, Beast, n their fave Kirby cover is) Iceman, Marvel Girl) TM & ©2003 Marvel Photocopies of Jack’s uninked pencils from Characters, Inc. -

Bobby in Movieland Father Francis J

Xavier University Exhibit Father Francis J. Finn, S.J. Books Archives and Library Special Collections 1921 Bobby in Movieland Father Francis J. Finn S.J. Xavier University - Cincinnati Follow this and additional works at: http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/finn Recommended Citation Finn, Father Francis J. S.J., "Bobby in Movieland" (1921). Father Francis J. Finn, S.J. Books. Book 6. http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/finn/6 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Library Special Collections at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Father Francis J. Finn, S.J. Books by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • • • In perfect good faith Bobby stepped forward, passed the dir ector, saying as he went, "Excuse me, sir,'' and ignoring Comp ton and the "lady" and "gentleman," strode over to the bellhop. -Page 69. BOBBY IN MO VI ELAND BY FRANCIS J. FINN, S.J. Author of "Percy Wynn," "Tom Playfair," " Harry Dee," etc. BENZIGER BROTHERS NEw Yonx:, Cmcnrn.ATI, Cmc.AGO BENZIGER BROTHERS CoPYlUGBT, 1921, BY B:n.NZIGEB BnoTHERS Printed i11 the United States of America. CONTENTS CHAPTER 'PAGB I IN WHICH THE FmsT CHAPTER Is WITHIN A LITTLE OF BEING THE LAST 9 II TENDING TO SHOW THAT MISFOR- TUNES NEVER COME SINGLY • 18 III IT NEVER RAINS BUT IT PouRs • 31 IV MRs. VERNON ALL BUT ABANDONS Ho PE 44 v A NEW WAY OF BREAKING INTO THE M~~ ~ VI Bonny ENDEA vo:r:s TO SH ow THE As TONISHED CoMPTON How TO BE- HAVE 72 VII THE END OF A DAY OF SURPRISES 81 VIII BonnY :MEETS AN ENEMY ON THE BOULEVARD AND A FRIEND IN THE LANTRY STUDIO 92 IX SHOWING THAT IMITATION Is NOT AL WAYS THE SINCEREST FLATTERY, AND RETURNING TO THE MISAD- VENTURES OF BonBY's MoTHER. -

Dark X-Men 5 Cbr

Dark x-men 5 cbr Dark X-Men #1 - 5 Free Download. Get FREE The Dark X-Men are a Marvel Comics comic-book team. They made CBR and/ file. It's the final showdown between the Dark X-Men and X-Man, all within the mind of Norman Osborn. Can the rag-tag group of villains take down. UTOPIA TIE-IN Who are the Dark X-Men and how did they come to be? FIND OUT HERE! Each issue has 3 page stories, each dedicated to. Download Free Comics» Tag cloud» Dark X-Men. Dark X-Men # Complete Dark X-Men - The Beginning # Complete. 3 issues pages | year. From the dust of UTOPIA comes DARK X-MEN! Never one to say “die”, Norman Osborn is keeping what's left of HIS X-Men alive. MYSTIQUE! DARK BEAST! Dark X-Men # Complete (). Publisher: Marvel / Collections. Dark X-Men - The Beginning # Complete. 3 issues pages | мb. Tags: Dark X-Men. UTOPIA TIE-IN Who are the Dark X-Men and how did they come to be? FIND OUT HERE! Each issue has 3 page stories, each dedicated to one of the Dark. Dark X-men #2 preview · Dec. 4th, . Dark Avengers/Uncanny X-Men: "Utopia" Part 5 · Aug. Five solicitations for July courtesy of Newsarama and CBR. Dark X-Men #1 (Marvel Comics) - From the dust of UTOPIA comes DARK X- MEN! Never one to say “die”, Marvel Comics's Dark X-Men Issue # 5 # 5. $ "The Dark Phoenix Saga" is an extended X-Men storyline in the fictional Marvel Comics . -

BTC Catalog 172.Pdf

Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. ~ Catalog 172 ~ First Books & Before 112 Nicholson Rd., Gloucester City NJ 08030 ~ (856) 456-8008 ~ [email protected] Terms of Sale: Images are not to scale. All books are returnable within ten days if returned in the same condition as sent. Books may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. All items subject to prior sale. Payment should accompany order if you are unknown to us. Customers known to us will be invoiced with payment due in 30 days. Payment schedule may be adjusted for larger purchases. Institutions will be billed to meet their requirements. We accept checks, VISA, MASTERCARD, AMERICAN EXPRESS, DISCOVER, and PayPal. Gift certificates available. Domestic orders from this catalog will be shipped gratis via UPS Ground or USPS Priority Mail; expedited and overseas orders will be sent at cost. All items insured. NJ residents please add 7% sales tax. Member ABAA, ILAB. Artwork by Tom Bloom. © 2011 Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. www.betweenthecovers.com After 171 catalogs, we’ve finally gotten around to a staple of the same). This is not one of them, nor does it pretend to be. bookselling industry, the “First Books” catalog. But we decided to give Rather, it is an assemblage of current inventory with an eye toward it a new twist... examining the question, “Where does an author’s career begin?” In the The collecting sub-genre of authors’ first books, a time-honored following pages we have tried to juxtapose first books with more obscure tradition, is complicated by taxonomic problems – what constitutes an (and usually very inexpensive), pre-first book material. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Braves' Bulletin Issue #15 May 2016

Braves’ Bulletin May 2016, Issue 15 Remembering Landy James By Maya Masonholder Inside this issue: Teacher Feature 2 Jokes 2 Meet Charles Baker 3 Word Search 3 Mother’s Day 4 LCMS Sports 5 Honoring a legend- Landy Meet Jenna Rudig 6 James was a great man. He was born Memorial Day 6 June 22, 1930. A Swinomish tribal member, Landy was a standout Weird Facts 7 student and athlete at Meet 7 La Conner High School. He earned a scholarship to Washington State Dr. Tim Bruce 7 University after graduating from Student Poll 8 La Conner High School in 1948. Student Artwork 8 While attending Washington State University, Landy majored in Contest 9 education and lettered in football and baseball. Landy graduated from Newspaper Staff: Washington State University in 1953. • Lexy Almaraz His first teaching job was in • Ace Baker Wilbur, Washington, in 1954. From 1955-1968, he taught science and coached football at Mead High School in Spokane. The following • Charles Baker year, Landy came back home to La Conner and Swinomish. From • Kaylanna Guerrero- 1968 to 1976, he served on the Swinomish Tribal Senate. He was the Gobert tribal chairman from 1974 to 1976. Landy taught at La Conner High School and coached the football team. His all-time coaching record Allison Hill • was 181-89-3 in football. Besides football, he coached basketball, and • Sarah Malcomson his 1984 and 1985 teams made the state tournament. • Maya Masonholder After retiring, Landy served as the liason between the La Conner School District and the Swinomish Tribe. Landy James • Maya Medeiros passed away June 3, 1997. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

Schurken Im Batman-Universum Dieser Artikel Beschäftigt Sich Mit Den Gegenspielern Der ComicFigur „Batman“

Schurken im Batman-Universum Dieser Artikel beschäftigt sich mit den Gegenspielern der Comic-Figur ¹Batmanª. Die einzelnen Figuren werden in alphabetischer Reihenfolge vorgestellt. Dieser Artikel konzentriert sich dabei auf die weniger bekannten Charaktere. Die bekannteren Batman-Antagonisten wie z.B. der Joker oder der Riddler, die als Ikonen der Popkultur Verankerung im kollektiven Gedächtnis gefunden haben, werden in jeweils eigenen Artikeln vorgestellt; in diesem Sammelartikel werden sie nur namentlich gelistet, und durch Links wird auf die jeweiligen Einzelartikel verwiesen. 1 Gegner Batmans im Laufe der Jahrzehnte Die Gesamtheit der (wiederkehrenden) Gegenspieler eines Comic-Helden wird im Fachjargon auch als sogenannte ¹Schurken-Galerieª bezeichnet. Batmans Schurkengalerie gilt gemeinhin als die bekannteste Riege von Antagonisten, die das Medium Comic dem Protagonisten einer Reihe entgegengestellt hat. Auffällig ist dabei zunächst die Vielgestaltigkeit von Batmans Gegenspielern. Unter diesen finden sich die berüchtigten ¹geisteskranken Kriminellenª einerseits, die in erster Linie mit der Figur assoziiert werden, darüber hinaus aber auch zahlreiche ¹konventionelleª Widersacher, die sehr realistisch und daher durchaus glaubhaft sind, wie etwa Straûenschläger, Jugendbanden, Drogenschieber oder Mafiosi. Abseits davon gibt es auch eine Reihe äuûerst unwahrscheinlicher Figuren, wie auûerirdische Welteroberer oder extradimensionale Zauberwesen, die mithin aber selten geworden sind. In den frühesten Batman-Geschichten der 1930er und 1940er Jahre bekam es der Held häufig mit verrückten Wissenschaftlern und Gangstern zu tun, die in ihrem Auftreten und Handeln den Flair der Mobster der Prohibitionszeit atmeten. Frühe wiederkehrende Gegenspieler waren Doctor Death, Professor Hugo Strange und der vampiristische Monk. Die Schurken der 1940er Jahre bilden den harten Kern von Batmans Schurkengalerie: die Figuren dieser Zeit waren vor allem durch die Abenteuer von Dick Tracy inspiriert, der es mit grotesk entstellten Bösewichten zu tun hatte. -

Supergirl: Bizarrogirl Online

YouMt [Read ebook] Supergirl: Bizarrogirl Online [YouMt.ebook] Supergirl: Bizarrogirl Pdf Free Sterling Gates ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1720578 in eBooks 2015-10-27 2015-10-27File Name: B016Z454HS | File size: 57.Mb Sterling Gates : Supergirl: Bizarrogirl before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Supergirl: Bizarrogirl: 5 of 5 people found the following review helpful. The last Supergirl trade (before New 52) contains 3 arcs and resolves threads from previous volumes (and War of Supermen)By R. H.This is the last trade collection from Supergirl before the New 52 and contains 3 arcs. (DC cancelled the Good-looking Corpse trade that was supposed to come after this one.)The first and longest arc deals with the trade's title, Bizarrogirl, and the story there accomplishes much in allowing Supergirl to move beyond the events of the War of the Supermen and also helping out Bizarro's cuboid Earth (yep, this is the same one from Superman: Escape From Bizarroworld). The adventure is very fun, full of fights and hilarity (as expected from stories involving Bizarros). Plus, the emotions explored here work well in Supergirl facing her doubts and self-inflicted guilt from the aforementioned war.The second arc is an entertaining one-shot with the Legion of Superheros (although a different iteration from previous Supergirl trades).The final arc deals with a seemingly mundane villain, but the context in this final arc finally brings to a closure a previously unresolved thread from earlier Supergirl trades. -

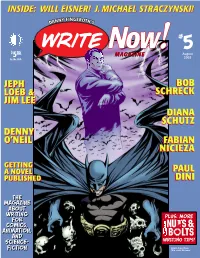

Inside: Will Eisner! J. Michael Straczynski!

IINNSSIIDDEE:: WWIILLLL EEIISSNNEERR!! JJ.. MMIICCHHAAEELL SSTTRRAACCZZYYNNSSKKII!! $ 95 MAGAAZZIINEE August 5 2003 In the USA JJEEPPHH BBOOBB LLOOEEBB && SSCCHHRREECCKK JJIIMM LLEEEE DIANA SCHUTZ DDEENNNNYY OO’’NNEEIILL FFAABBIIAANN NNIICCIIEEZZAA GGEETTTTIINNGG AA NNOOVVEELL PPAAUULL PPUUBBLLIISSHHEEDD DDIINNII Batman, Bruce Wayne TM & ©2003 DC Comics MAGAZINE Issue #5 August 2003 Read Now! Message from the Editor . page 2 The Spirit of Comics Interview with Will Eisner . page 3 He Came From Hollywood Interview with J. Michael Straczynski . page 11 Keeper of the Bat-Mythos Interview with Bob Schreck . page 20 Platinum Reflections Interview with Scott Mitchell Rosenberg . page 30 Ride a Dark Horse Interview with Diana Schutz . page 38 All He Wants To Do Is Change The World Interview with Fabian Nicieza part 2 . page 47 A Man for All Media Interview with Paul Dini part 2 . page 63 Feedback . page 76 Books On Writing Nat Gertler’s Panel Two reviewed . page 77 Conceived by Nuts & Bolts Department DANNY FINGEROTH Script to Pencils to Finished Art: BATMAN #616 Editor in Chief Pages from “Hush,” Chapter 9 by Jeph Loeb, Jim Lee & Scott Williams . page 16 Script to Finished Art: GREEN LANTERN #167 Designer Pages from “The Blind, Part Two” by Benjamin Raab, Rich Burchett and Rodney Ramos . page 26 CHRISTOPHER DAY Script to Thumbnails to Printed Comic: Transcriber SUPERMAN ADVENTURES #40 STEVEN TICE Pages from “Old Wounds,” by Dan Slott, Ty Templeton, Michael Avon Oeming, Neil Vokes, and Terry Austin . page 36 Publisher JOHN MORROW Script to Finished Art: AMERICAN SPLENDOR Pages from “Payback” by Harvey Pekar and Dean Hapiel. page 40 COVER Script to Printed Comic 2: GRENDEL: DEVIL CHILD #1 Penciled by TOMMY CASTILLO Pages from “Full of Sound and Fury” by Diana Schutz, Tim Sale Inked by RODNEY RAMOS and Teddy Kristiansen .