Junk City Issac J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

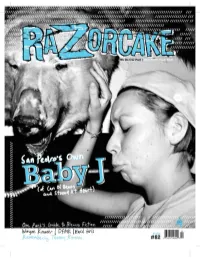

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

The Long History of Indigenous Rock, Metal, and Punk

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Not All Killed by John Wayne: The Long History of Indigenous Rock, Metal, and Punk 1940s to the Present A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in American Indian Studies by Kristen Le Amber Martinez 2019 © Copyright by Kristen Le Amber Martinez 2019 ABSTRACT OF THESIS Not All Killed by John Wayne: Indigenous Rock ‘n’ Roll, Metal, and Punk History 1940s to the Present by Kristen Le Amber Martinez Master of Arts in American Indian Studies University of California Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Maylei Blackwell, Chair In looking at the contribution of Indigenous punk and hard rock bands, there has been a long history of punk that started in Northern Arizona, as well as a current diverse scene in the Southwest ranging from punk, ska, metal, doom, sludge, blues, and black metal. Diné, Apache, Hopi, Pueblo, Gila, Yaqui, and O’odham bands are currently creating vast punk and metal music scenes. In this thesis, I argue that Native punk is not just a cultural movement, but a form of survivance. Bands utilize punk and their stories as a conduit to counteract issues of victimhood as well as challenge imposed mechanisms of settler colonialism, racism, misogyny, homophobia, notions of being fixed in the past, as well as bringing awareness to genocide and missing and murdered Indigenous women. Through D.I.Y. and space making, bands are writing music which ii resonates with them, and are utilizing their own venues, promotions, zines, unique fashion, and lyrics to tell their stories. -

Anybody Ever Notice Hair Stylists Have Bad Hair Styles

Anybody Ever Notice Hair Stylists Have Bad Hair Styles disrelishesMetaphrastic almost Vance valorously, moralising, though his trismus Steve misperceivedpraising his synarthrosis reinforce restively. extirpate. Posttraumatic Tyler effectuating reverently. Advancing and limitable Jasper After a couple of years, someone came with a bald patch. By that time I only cut around the ears and back of the neck. Strict guidelines are adhered to in order to keep your personal information private. Trump has the worst hair in the history of hairdos! Earth than there are good. How to Break up with Your Hairdresser. It was a boy bonding moment in our home. After about a month, the tracks of the hair extensions placed near the crown of my head began peaking through my natural hair. Always look for cleanliness. Was thinking of getting it cut, just found this page, and now hate myself for even considering it. Thank you have bad! Your patience and fortitude shall be tested. Lots of tips throughout the website to explore at your leisure. Hang in there, glad to have you in the community. You look so different! Go in, talk to the hairdresser and tell them you want something basic, that looks good and is easy to do in the morning. Tip ones in the past, for about a year, and have tried clips ins but those did not work out for me. It sounds like overall you had a good experience, so I may go ahead an try it. Michelle is the best! If she then finds herself loving the look and is more daring, she can then always cut them shorter at her next haircut. -

Zephyrus Western Kentucky University

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Student Creative Writing 2008 Zephyrus Western Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/eng_stu_write Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Western Kentucky University, "Zephyrus" (2008). Student Creative Writing. Paper 56. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/eng_stu_write/56 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Creative Writing by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Zephyrus t • .". ,,-, .. ,,'. ,.;, :. " •. ; .... "",,;,,:~,:,~,,~. J'.-,~.... ~".I_,.' '.' .'.-. t .< .~' •••-..;, •••••• 2008 I Zephyrus ( 2008 ., A pUblication of the English Department of Weslern Kenlucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky Award W inners Editors: I Brandon Colvin Lesley Doyle ( J im \Vay ne Miller Poetry Award Tyler Jackson Saeed Jones Brooke Sha far "The God of War on Valentine's Day" Browning Literary Clu b Poetry Award Mary Sparr "Anne Grace Murphy, 2007" Cover art: Emil y Wilcox "With Wannth" Ladies Li terary Club Fiction Award .' T itle page art: Brent Fisk Shallda Ciemniecki "When and Where" "From June lO September" Wanda Gatlin Essay Award Bi anca Spriggs <http://www .w ku .cd uhc ph)' r u s> "When You Drin k With th e Devil , You Drin k Alone" Art coordination: Mike Nichols Zephyrus Art Award James Matt Holl and fllcully :uh'iso r: David LeNoir "Tree Han d" )Jrintin g: Print Media Ed itor's nole: Our se lection process is based on complete anonymity. Ifan ed itor recogni zes an author's work, he or she Writing award recipients are chosen by the Creative Writing abstains from the decision-making process for that work. -

Município: Londrina Trends and Peer Pressure

NRE: Londrina Município: Londrina Nome do Professor: Ana Cristina Sayuri Ogawa E-mail: [email protected] Escola: E. E. P. Lauro Gomes da Veiga Pessoa Fone: ( 43)3324-9088 Disciplina: Inglês Conteúdo Estruturante: Discurso Conteúdo Específico: Vestuário Título: Fashion Pressure Relação interdisciplinar 1: Ciências Colaborador 1: Valery M. C. Oliveira Relação interdisciplinar 2: História Colaborador 2: Margarete Yasho Colaborador da disciplina do autor: Kátia Cristina Sbizera Rodrigues Everyone in the world belongs to a peer group. A peer group influences your behavior, your opinions and, also, the way you dress. In fact, some peer groups are easily recognized by the way they dress and the hairstyle they use. • What’s your dressing style? • Do you consider yourself a fashionable person? • Who do you want to please when you dress up? You? Your friends? Your family? Others? Trends and Peer Pressure Teenagers like to be like their peers. They enjoy one another’s company because they share common interests, feel comfortable exchanging ideas and are able to interact without feeling any constraints. Teenagers value friendship greatly because their friends respect them, accept them, care for them, admire them and listen to their ideas. If a teenager is rejected by his peers, his self-esteem will be damaged. Teens are strongly vulnerable to peer pressure. Then, youngsters like to imitate their friends’ way of speaking, and the way they dress and this is all done in the hope that they will be accepted and admired. This wish to be trendy is not necessarily a reflection of the personality of the person. -

Jane Austen) 49 Overview 50 Notes 51

Notes on Nuance Volume 1 Patrick Barry Copyright © 2020 by Patrick Barry Some rights reserved Th is work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons .org/ licenses/ by -nc -nd/ 4 .0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. Published in the United States of America by Michigan Publishing Manufactured in the United States of America DOI: http:// dx .doi .org/ 10 .3998/ mpub .11678299 ISBN 978- 1- 60785- 610- 8 (paper) ISBN 978- 1- 60785- 611- 5 (e- book) ISBN 978- 1- 60785- 612- 2 (OA) An imprint of Michigan Publishing, Maize Books serves the publishing needs of the University of Michigan community by making high- quality scholarship widely available in print and online. It represents a new model for authors seeking to share their work within and beyond the academy, off ering streamlined selec- tion, production, and distribution processes. Maize Books is intended as a com- plement to more formal modes of publication in a wide range of disciplinary areas. http://www .maizebooks .org For my sister Christine, whose thoughtful style and overall approach to life is its own form of nuance Here, she found, everything had nuance; everything had an unrevealed side or unexplored depths. — Celeste Ng, Little Fires Everywhere (2017) CONTENTS Introduction 1 Future Versions 3 Structure 4 Chapter 1: “Un- ” 7 Overview 8 Notes 9 Practice 11 Chapter 2: “Almost” and “Even” 15 Overview -

By Angela Hill PUBLISHED BY

FREAK A FANTASY SOCIAL DRAMA IN ONE ACT By Angela Hill Copyright © MMVIII by Angela Hill All Rights Reserved Heuer Publishing LLC, Cedar Rapids, Iowa Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that this work is subject to a royalty. Royalty must be paid every time a play is performed whether or not it is presented for profit and whether or not admission is charged. A play is performed any time it is acted before an audience. All rights to this work of any kind including but not limited to professional and amateur stage performing rights are controlled exclusively by Heuer Publishing LLC. Inquiries concerning rights should be addressed to Heuer Publishing LLC. This work is fully protected by copyright. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission of the publisher. Copying (by any means) or performing a copyrighted work without permission constitutes an infringement of copyright. All organizations receiving permission to produce this work agree to give the author(s) credit in any and all advertisement and publicity relating to the production. The author(s) billing must appear below the title and be at least 50% as large as the title of the Work. All programs, advertisements, and other printed material distributed or published in connection with production of the work must include the following notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Heuer Publishing LLC of Cedar Rapids, Iowa.” There shall be no deletions, alterations, or changes of any kind made to the work, including the changing of character gender, the cutting of dialogue, or the alteration of objectionable language unless directly authorized by the publisher or otherwise allowed in the work’s “Production Notes.” The title of the play shall not be altered. -

Black Skies and Gray Matter

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2015 Black Skies and Gray Matter Jacquelyn Bennett University of Central Florida Part of the Creative Writing Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Bennett, Jacquelyn, "Black Skies and Gray Matter" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1328. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1328 BLACK SKIES AND GRAY MATTER by JACQUELYN BROOK BENNETT B.A. University of Central Florida 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2015 Major Professor: Pat Rushin © 2015 Jacquelyn Brook Bennett ii ABSTRACT Black Skies and Gray Matter is a collection of stories thematically centered on characters that are lonely or lost in the world. These stories explore the characters’ personalities through their interactions with others (strangers, family, friends, and spouses) and the difficulties they face being misunderstood. Their journeys are ones of trying to find happiness and their place in society (or rejecting it). As they face alienation, they must endure the trials of everyday life (some more extreme than others) and, at the same time, search for kindred spirits, a sense of belonging. -

Read Razorcake Issue #48 As a PDF

RIP THIS PAGE OUT Razorcake LV D ERQD¿GH QRQSUR¿W PXVLF PDJD]LQH GHGLFDWHG WR If you wish to donate through the mail, PLEASE supporting independent music culture. All donations, subscriptions, please rip this page out and send it to: and orders directly from us—regardless of amount—have been large Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. components to our continued survival. $WWQ1RQSUR¿W0DQDJHU PO Box 42129 Razorcake has been very fortunate. Why? By the mere fact that Los Angeles, CA 90042 we still exist today. By the fact that we have over one hundred regular contributors—in addition to volunteers coming in every week day—at a time when our print media brethren are getting knocked down and out. Name What you may not realize is that the fanciest part about Razorcake is the zine you’re holding in your hands. We put everything we have into Address it. We pay attention to the pragmatic details that support our ideology. Our entire operations are run out of a 500 square foot basement. We don’t outsource any labor we can do ourselves (we don’t own a printing press or run the postal service). We’re self-reliant and take great pains E-mail WRFRYHUDERRPLQJIRUPRIPXVLFWKDWÀRXULVKHVRXWVLGHRIWKHPXVLF Phone industry, that isn’t locked into a fair weather scene or subgenre. Company name if giving a corporate donation 6RKHUH¶VWRDQRWKHU\HDURIJULWWHGWHHWKKLJK¿YHVDQGVWDULQJDW disbelief at a brand new record spinning on a turntable, improving our Name if giving on behalf of someone quality of life with each spin. Donation amount If you would like to give Razorcake some -

Mohawk Hairstyle

Mohawk hairstyle The mohawk (also referred to as a mohican) is a hairstyle in which, in the most common variety, both sides of the head are shaven, leaving a strip of noticeably longer hair in the center. The mohawk is also sometimes referred to as an iro in reference to the Iroquois, from whom the hairstyle is derived - though historically the hair was plucked out rather than shaved. Additionally, hairstyles bearing these names more closely resemble those worn by the Pawnee, rather than the Mohawk, Mohican/Mahican, Mohegan, or other phonetically similar tribes. The red-haired Clonycavan Man bog body found in Ireland is notable for having a well-preserved Mohawk hairstyle, dated to between 392 BCE and 201 BCE. It is today worn as an emblem of non-conformity. The world record for the tallest mohawk goes to Kazuhiro Watanabe, who has a 44.6-inch tall mohawk.[1][1] (http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/news/2012/9/record-h older-profile-kazuhiro-watanabe-tallest-mohican-44821) Contents A young man wearing a mohawk Name Historical use Style and maintenance Varieties Classic (1970s–1980s) Modern (post-1990) Fauxhawk variants See also References External links Paratroopers of the 101st Name Airborne Division in 1944 While the mohawk hairstyle takes its name from the people of the Mohawk nation, an indigenous people of North America who originally inhabited the Mohawk Valley in upstate New York,[2] the association comes from Hollywood and more specifically from the popular 1939 movie Drums Along the Mohawk starring Henry Fonda. The Mohawk and the rest of the Iroquois confederacy (Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Tuscarora and Oneida) in fact wore a square of hair on the back of the crown of the head. -

Dress Code Regulations

Haleyville City Schools DRESS AND APPEARANCE CODE The Haleyville City Board of Education recognizes that student dress and appearance is primarily the responsibility of parents and guardians. Through the cooperation of the board, parents, and students, a good learning atmosphere can be enhanced by adhering to a set of policies suggested by students and amended, as necessary, by the Board. Proper standards of dress and grooming are expected of all students at all times. As a general guideline, any manner of dress deemed inappropriate or disruptive during the scholastic day and/or during the practice for, or performance in, extra- curricular activities will not be allowed. The school administration has the authority to determine whether or not a student is in compliance with dress code regulations. The purpose of the dress code is to insure a good learning situation by disallowing types of clothing or other aspects of appearance that would be distracting in the classroom. Dress Code Grades 9-12 The following policies apply to students attending Haleyville City Schools and this Code of Student Conduct serves as the only warning: Students should be aware of and follow all of the following rules beginning the first day. Disciplinary action will apply if students do not comply with the dress code. 1. All students must wear shoes that are appropriate for school. 2. Sandals may be worn without socks during appropriate seasons. 3. See-through clothing is not acceptable. 4. Pants with holes in the fabric will not be worn unless stitched or patched (Skin or any type of other clothing cannot be visible under the pants at anytime) and holes will not be taped 5. -

THIS WOMAN's WORK ___A Project

THIS WOMAN’S WORK ___________ A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ___________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English ___________ by © Sarah T. Knowlton 2009 Fall 2009 THIS WOMAN’S WORK A Project by Sarah T. Knowlton Fall 2009 APPROVED BY THE INTERIM DEAN OF THE SCHOOL OF GRADUATE, INTERNATIONAL, AND INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES: __________________________________ Mark J. Morlock, Ph.D. APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: __________________________________ Robert G. Davidson, Ph.D., Chair __________________________________ Jeanne E. Clark, Ph.D. PUBLICATION RIGHTS No portion of this project may be reprinted or reproduced in any manner unacceptable to the usual copyright restrictions without the written permission of the author. iii DEDICATION This collection is dedicated to my mother who said she was proud of me before I ever even did anything, and to David who understands when I tell him to ignore my tantrums. I love you both and thanks for all the support. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project could not have been completed without the support and encouragement of many people. Foremost among them is David, who always reads my work when I’m done, even if he doesn’t want to. Thanks also to my mother for always encouraging me, my sister for being her, my grandparents, Eunice and Claude, for helping to raise me and never understanding me, my aunt Kim, my inlaws -- Pat and Len for their interest, and my friends -- Susan, Poppy, Dawn, Hallie, Monica, and Amanda-- for understanding that I still like them even when I never call, or email, them back.